Index:

Panama Grit & Glory

By Bob and Carolyn Schmidt

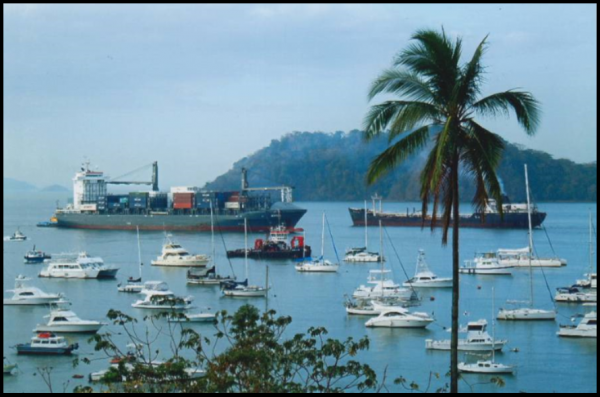

In early March 2017 eighteen members of U.S. canal societies joined a tour of the Panama Canal initiated by the Canal Society of Indiana. Although some had traveled previously through this 8th wonder of the world on a cruise ship, they came to learn the details of operation and see the associated surroundings. Road Scholar sponsors this tour (9901RJ) from October – March. It is very popular and, based on our experiences, you will see why.

Tour participants were booked on a variety of flights from the U.S. We, Bob and Carolyn Schmidt, joined others at Atlanta and then flew to Panama. We arrived Saturday March 4th about 9:45 PM at the Tocumen International Airport near Panama City, which is located on the Pacific coast. Once we cleared customs and our group assembled we were driven by a small van to the Country Inn & Suites right on the entry way to the canal. From our room’s balcony we could see and hear the sounds of the large cargo ships which move through the canal 24 / 7.

Tour participants were booked on a variety of flights from the U.S. We, Bob and Carolyn Schmidt, joined others at Atlanta and then flew to Panama. We arrived Saturday March 4th about 9:45 PM at the Tocumen International Airport near Panama City, which is located on the Pacific coast. Once we cleared customs and our group assembled we were driven by a small van to the Country Inn & Suites right on the entry way to the canal. From our room’s balcony we could see and hear the sounds of the large cargo ships which move through the canal 24 / 7.

On Sunday after a hearty breakfast at the hotel, we assembled in a conference room to meet our guides and learn about the planned activities and tour logistics. “Archie” Kirchman, our guide, graduated from the University of Panama, worked with tourism for over 20 years and has been in charge of this particular tour for 13 years. Since our group was one of the largest ever on this tour we had a second group leader, Wendell Martinez, who was educated at the graduate level and was a naturalist, bird lover and interpreter. Archie was from Panama City on the Pacific side and Wendell was from Colon on the Atlantic coast. When we told our leaders that we had some real canal enthusiasts in our group they chuckled and said, “We can handle them.”

Of the 50 tour participants, eighteen were from canal societies as follows: Dave & Audrey Barber – American Canal Society; Bob & Linda Barth – Canal Society of New Jersey; Arnie Bandstra & Steve Wasilewski – Illinois & Michigan canal; Sally Bancroft, Carl & Barb Bauer, Tom & Diane Fledderjohann, Jerry & Barb Lehman, Mike & Tom Morthorst, Bob & Carolyn Schmidt, and Kay Sheldon — CSI/CSO. We were all issued a personal listening device to be used throughout the week. By 10:30 AM we were ready and anxious to begin exploring. We used three vans to tour the narrow streets in the old Canal Zone and old Panama City.

Of the 50 tour participants, eighteen were from canal societies as follows: Dave & Audrey Barber – American Canal Society; Bob & Linda Barth – Canal Society of New Jersey; Arnie Bandstra & Steve Wasilewski – Illinois & Michigan canal; Sally Bancroft, Carl & Barb Bauer, Tom & Diane Fledderjohann, Jerry & Barb Lehman, Mike & Tom Morthorst, Bob & Carolyn Schmidt, and Kay Sheldon — CSI/CSO. We were all issued a personal listening device to be used throughout the week. By 10:30 AM we were ready and anxious to begin exploring. We used three vans to tour the narrow streets in the old Canal Zone and old Panama City.

Our hotel was in the area called Fort Grant in the old Canal Zone, a 10-mile-wide strip which, like the Wabash & Erie Canal, extended 5 miles on either side of the Canal route. When under U.S. administration the primary use for the canal was for military purposes— moving ships with military ordinance and troops. The canal opened in 1914 just shortly after war broke out in Europe. Forts, gun emplacements and soldiers were there to defend the canal from Germany and other threats. Leaving the hotel we passed by old housing barracks and clubs, some now converted to other uses.

Our hotel was in the area called Fort Grant in the old Canal Zone, a 10-mile-wide strip which, like the Wabash & Erie Canal, extended 5 miles on either side of the Canal route. When under U.S. administration the primary use for the canal was for military purposes— moving ships with military ordinance and troops. The canal opened in 1914 just shortly after war broke out in Europe. Forts, gun emplacements and soldiers were there to defend the canal from Germany and other threats. Leaving the hotel we passed by old housing barracks and clubs, some now converted to other uses.

Our vans then took us to the Panama Canal Administration Building. This impressive 1914 structure sits atop a natural hill. In front is a monument dedicated to George Washington Goethals, who was the Chief Engineer and President of the Panama Canal Commission from 1907 -1914. He subsequently became the first Governor of the Panama Canal Zone from 1914-1917. The monument’s three stone ledges represent the old 3 lock systems, Gatun, Pedro Miguel and Miraflores. We were hoping to be able to go inside the building to see its marble staircases and murals, but security was very tight. We were denied admittance because a meeting was in progress. We did see youngsters sliding down the grassy slopes and young ladies standing before the monument for photo sessions.

In front of the Goethals monument a long planting of palm trees stood to show the size of the original locks, 1050 feet long by 110 wide. Goethals finalized the size of the locks to accommodate the largest battleships at that time. Gatun Lake is 85 feet above sea level. On the Caribbean side of Panama three locks, each with two chambers side by side, lift boats a total of 85 feet into Gatun Lake. On the Pacific side there is one set of side by side locks at Pedro Miguel that has a lift of 31 feet and two locks with side by side chambers at Miraflores that have a lift of 54, which makes the total lift on the Pacific side of 85 feet. Actually, extreme tidal changes on the Pacific require that the Miraflores locks can lift from 43 – 64.5 feet. Our guides pointed out that the largest ships going through the old locks are called “Panamax.” Although there isn’t a new canal, there are new locks on either side of Gatun lake that are 1400 feet long and 180 feet wide. Ships that are too large for the old locks are called “Neo-Panamax.” Some container ships currently under construction will even exceed the size of the new locks.

In front of the Goethals monument a long planting of palm trees stood to show the size of the original locks, 1050 feet long by 110 wide. Goethals finalized the size of the locks to accommodate the largest battleships at that time. Gatun Lake is 85 feet above sea level. On the Caribbean side of Panama three locks, each with two chambers side by side, lift boats a total of 85 feet into Gatun Lake. On the Pacific side there is one set of side by side locks at Pedro Miguel that has a lift of 31 feet and two locks with side by side chambers at Miraflores that have a lift of 54, which makes the total lift on the Pacific side of 85 feet. Actually, extreme tidal changes on the Pacific require that the Miraflores locks can lift from 43 – 64.5 feet. Our guides pointed out that the largest ships going through the old locks are called “Panamax.” Although there isn’t a new canal, there are new locks on either side of Gatun lake that are 1400 feet long and 180 feet wide. Ships that are too large for the old locks are called “Neo-Panamax.” Some container ships currently under construction will even exceed the size of the new locks.

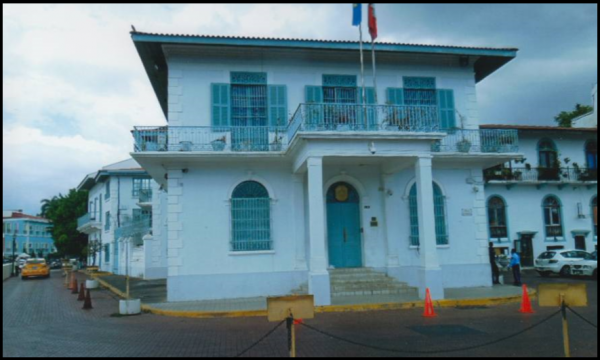

Next we proceeded to Casco Viejo “Old Quarter,” the second Panama City. It was built by the Spanish in 1673 on a peninsula as a walled city to protect it from attack. The original Panama Viejo, which was built in 1519 on the coast 5 miles away, was looted by Captain Henry Morgan in 1671. He crossed the isthmus with about 1200 men. This original location is now part of today’s Panama City.

Next we proceeded to Casco Viejo “Old Quarter,” the second Panama City. It was built by the Spanish in 1673 on a peninsula as a walled city to protect it from attack. The original Panama Viejo, which was built in 1519 on the coast 5 miles away, was looted by Captain Henry Morgan in 1671. He crossed the isthmus with about 1200 men. This original location is now part of today’s Panama City.

In Casco Viejo we wound through narrow streets until we reached the Panama Canal Museum established in 1997. This building, originally built as the Grand Hotel, served as the Canal Administration building for the French and later the Americans. The museum had some nice exhibits but the text was all in Spanish. Archie explained the various stations via our headsets. The museum sits right on the Plaza of Independence where there was a lot of activity including a market. After leaving the museum Archie kept us moving along on foot explaining that we were there for a cultural experience not a shopping spree. As we walked past several tempting shops many of the women looked distressed, but they kept going so as not to be left behind.

We next reached the ruins of Santo Domingo, a church and convent, which was built in 1678. In its ruins there remains the ‘flat arch’ (upper right), which survived the fire of 1756. It was used to prove to American politicians and engineers that Panama was not in an active earthquake zone as was Nicaragua and that this area was stable enough for a canal.

We stopped at the stairs of the current French Embassy to catch our breath and get out of the intense heat. Carl Bauer was the only brave soul in our group to walk up and around the Plaza de Francia. As we sat in the plaza someone spotted a Yellow Crown Night Heron. Others gazed at the spectacular view of Panama City with its skyline in the distance. Trump’s Ocean Club, the tallest building in the city, is a 70 story, 961 foot skyscraper that was completed in 2011.

We stopped at the stairs of the current French Embassy to catch our breath and get out of the intense heat. Carl Bauer was the only brave soul in our group to walk up and around the Plaza de Francia. As we sat in the plaza someone spotted a Yellow Crown Night Heron. Others gazed at the spectacular view of Panama City with its skyline in the distance. Trump’s Ocean Club, the tallest building in the city, is a 70 story, 961 foot skyscraper that was completed in 2011.

About 1:00 PM hungry canawlers boarded vans and headed to Sirena, a restaurant. We were served a buffet-style meal of curried chicken, pork, fruits, vegetables and cake for dessert.

About 1:00 PM hungry canawlers boarded vans and headed to Sirena, a restaurant. We were served a buffet-style meal of curried chicken, pork, fruits, vegetables and cake for dessert.

After lunch we took a brief siesta at our hotel. At 4:30 PM Jaime Roblete, who has worked in public relations and education for the Panama Canal Commission, presented a marvelous PowerPoint presentation on all aspects of the building and working of the canal. His presentation clearly demonstrated the operation of the new locks. He was able to field all of our technical questions on canal operations. At 7:00 PM we gathered on the hotel’s patio for a buffet dinner with a glass of wine or beer.

On Monday we boarded a 50-passenger bus and headed into the more remote rain forest. Panama has created several national parks in the canal drainage basin to protect their source of water. Fresh water is the essential ingredient for the canal and for the growing population of Panama, currently about 4.1 million. The country is just a little smaller than South Carolina, but it has about 500 rivers and 40% of the land area is jungle. For visitors from the U.S., Panama is in the U.S. Eastern time zone, the U.S. dollar is the currency in even exchange with the Balboa, and English is spoken/understood by most Panamanians. We also learned that Panama Canal runs north-south between the Caribbean (north) and the Pacific (south). Actually the Canal and Panama City are further east than Florida.

We stopped at a memorial site recognizing Chinese workers in Panama. It was near the foot of the Bridge of the Americas, which was completed in 1962 and crosses the entry into the Panama Canal. The first Chinese came to work on the railroad in 1854 and later the canal. Today they represent about 4% of the population of Panama. We had an excellent view of the bridge and of the activity on the approach to the Miraflores locks. Through our headsets Archie told us

We stopped at a memorial site recognizing Chinese workers in Panama. It was near the foot of the Bridge of the Americas, which was completed in 1962 and crosses the entry into the Panama Canal. The first Chinese came to work on the railroad in 1854 and later the canal. Today they represent about 4% of the population of Panama. We had an excellent view of the bridge and of the activity on the approach to the Miraflores locks. Through our headsets Archie told us  about our view of Panama City and the Port of Balboa in front of us. We learned that canal tolls are determined by the value of the cargo carried. At the port autos are off loaded from ships that can carry 3500 of them and driven to the Atlantic coast where they are reloaded or transferred to other ships. This is cheaper than sending them on the ship through the canal. We also learned to identify port authority tugs. They are black/blue with yellow tops versus the canal authority tugs that are black with white tops.

about our view of Panama City and the Port of Balboa in front of us. We learned that canal tolls are determined by the value of the cargo carried. At the port autos are off loaded from ships that can carry 3500 of them and driven to the Atlantic coast where they are reloaded or transferred to other ships. This is cheaper than sending them on the ship through the canal. We also learned to identify port authority tugs. They are black/blue with yellow tops versus the canal authority tugs that are black with white tops.

Ships transiting the canal are completely controlled by the Panama Canal Authority, which is separate from the government of Panama, and took over from the Panama Canal Commission. The canal tolls for Panamax and smaller vessels average about $125,000. Tolls for the Neo-Panamax can run from $500,000- $950,000. A cruise ship is about $419,000 per transit, which is one trip into the lake and one trip out. The ship does not need to cross the entire waterway. Commercial ships wait in the approach harbors for 48-96 hrs. Their toll must be transferred from their bank into the Canal Authority bank account 48 hours before transit. Priority is military, cruise and then commercial ships. The Canal Authority also has a bidding period so for additional dollars you can buy priority. Before the ships enter the canal channel a ship pilot from the Canal Authority boards the ship and is in complete control of all operations until the ship leaves the Panama Canal. This applies to all ships, boats, etc.

Both the French and the U.S. ran into much difficulty in the Culebra “Snake” Cut. They had to dig through the highest peak where the rock was hard and the soil slippery. Due to the heavy rainfall the sides of the canal at Culebra kept sliding down into the canal. A trench had to continually be widened. Today the sides of the cut are terraced, but there is only one lane of traffic. Ships have to go single file through it. In the morning large ships enter the dual locks from the Pacific and the Atlantic side into Gatun Lake and cross it. In the afternoon ships go back out using dual lanes at the old locks. This traffic requires some fancy regulation by the canal administrators. Dredging is a continuous operation. Plans are to widen the channel to allow two lane traffic for Neo-Panamax vessels by 2025.

The French Plan led by Ferdinand De Lesseps called for a sea level canal like the Suez Canal. The amount of excavation was grossly underestimated and the private company went into bankruptcy in 1889. The French plan called for changing the flow of the Chagres River from flowing into the Atlantic and diverting the river somehow into the Pacific, as the canal path was directly across the old path of the river. The U.S. plan was to dam the Chagres at Gatun by building a mile long dam creating the largest lake at the time. Gatun Lake was to be 85 feet above sea level with three sets of side by side locks on each end of the lake that would lift or lower ships back to the sea. To avoid the Pedro Miguel fault that runs across the canal, the Pacific locks were split into two separate complexes on either side of the fault, Pedro Miguel and Miraflores whereas the Atlantic side is one complex, Gatun Locks. The new locks are each built in one complex —Cocoli on the Pacific and Agua Clara on the Atlantic.

We proceeded on late Monday morning to the Madden Dam on the Chagres River. This dam was built in 1935 to provide flood control and hydro power on the river. Torrential rains threaten canal operations. This dam created Madden Lake that was renamed Alajuela when Panama took back the canal in 2000. As we walked around we spotted a bee’s nest in a nearby tree. As we headed to lunch at Gamboa, we stopped at Las Cruces Trail. Wendell told us that this route was created by the Spanish to bring gold from the Andes to Panama City and then to follow this trial to the Chagres River and then on to the Caribbean. We drove past new communities that were created when people were removed to build the new locks. We crossed the Centennial Bridge, completed in 2004, which carries the Pan American Highway across the Culebra Cut.

We proceeded on late Monday morning to the Madden Dam on the Chagres River. This dam was built in 1935 to provide flood control and hydro power on the river. Torrential rains threaten canal operations. This dam created Madden Lake that was renamed Alajuela when Panama took back the canal in 2000. As we walked around we spotted a bee’s nest in a nearby tree. As we headed to lunch at Gamboa, we stopped at Las Cruces Trail. Wendell told us that this route was created by the Spanish to bring gold from the Andes to Panama City and then to follow this trial to the Chagres River and then on to the Caribbean. We drove past new communities that were created when people were removed to build the new locks. We crossed the Centennial Bridge, completed in 2004, which carries the Pan American Highway across the Culebra Cut.

At Gamboa, the Chagres River enters Gatun Lake and the ships follow the old river route through the lake. We had a buffet lunch at the Gamboa Tarpon Club located on the bank of the Chagres. Some saw a few crocodiles and turtles on the shore. We then drove past dredging operations in the canal. One of the huge dredges was the “Titan,” which was shipped from Germany and is sometimes called “Herman the German.”

As we proceeded back south we passed the French Cemetery at Paraiso with many white crosses along the hillside. Each cross represented a hundred lives lost by the canal workers, who mostly came from the Caribbean islands and many were buried along the canal. The total loss of lives during the French construction is really unknown, but is estimated to be about 22,000. We stopped briefly at the Pedro Miguel locks to watch an auto carrier ship pass through the locks. Reaching Miraflores locks we watched a video about the locks and spent most of the time observing lock operations as portions of the museum were under construction.

As we proceeded back south we passed the French Cemetery at Paraiso with many white crosses along the hillside. Each cross represented a hundred lives lost by the canal workers, who mostly came from the Caribbean islands and many were buried along the canal. The total loss of lives during the French construction is really unknown, but is estimated to be about 22,000. We stopped briefly at the Pedro Miguel locks to watch an auto carrier ship pass through the locks. Reaching Miraflores locks we watched a video about the locks and spent most of the time observing lock operations as portions of the museum were under construction.

This Monday was the first day of school in Panama and traffic was tremendous. We finally reached the Intercontinental Hotel in Panama City for our evening meal. From the 6th floor we had a great view of the modern skyscrapers of the city and another great meal with canal friends.

We then headed back to the Country Inn & Suites for our 3rd night in the city. Archie again emphasized the importance of checking out at the front desk that night so that we could leave promptly at 7:00 AM Tuesday for our boat trip through the canal. The exact timing was unknown and depended on the Panama Canal Authority. Our boat had to be at a certain point by 7:30 AM.

(To be continued in the July issue of The Tumble)

Mary Hassett Martin – Canal Boat Captain

By Tom Castaldi

On May 1, 1842, Mary Ann Hassett was born in Ireland’s Tipperary County and at age four years emigrated from her home to America arriving in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1846. Her husband to be, Patrick Henry Martin was born in 1840, in Cincinnati and in 1858 the two were joined in marriage at Franklin, Ohio.

After the Civil War broke out Patrick Martin enlisted in the army as a Private on May 2, 1864 serving with of Ohio Company E, 146th Infantry Regiment mustering out on September 7, 1864. He returned to Ohio where he went canalling between Dayton, Ohio running on the Miami & Erie Canal to its connection with the Wabash & Erie Canal at Junction, Ohio and then on the Wabash & Erie. Eventually, operating two boats Martin’s route included landing at ports between Toledo, Ohio to Lafayette, Indiana and below.

Canal boat crews were usually described as a five-man team: captain, two steersmen, a driver for the horses or mules and a man to do the cooking but sometimes a woman. Captains were typically men folk who had to deal with rough and tumble boat hands. Nothing was motorized including the boat towed by animals. Work on board was done by hand. It also meant navigating past on-coming boats and moving through locks which, although rules governed such movement, were mostly ignored in favor of a boat crew who could fight with fists and clubs to determine who got first passage.

After Patrick died in 1871, his wife Mary Ann took over operating the boats during the last years of the old waterway. In 1874, the courts ordered the canal closed, and by 1876 a group of investors, with rail interests in mind, purchased the route from Lafayette to the Ohio state line. However, before the canal-era ended, Mary Ann Martin of Defiance, Ohio was issued a license to operate the canal boat John Jay with its 62 plus tonnage rating, its plain head and square stern, measuring 78 feet long and 13 feet wide on the Wabash & Erie Canal. A rather typical canal vessel, since these long narrow crafts had to be maneuvered into and out of lifting locks, which were constructed on a standard inside measurement of ninety feet long by fifteen feet wide chamber.

Other than having to deal with tough crewmen of the day Mrs. Martin was responsible for all manner of boat master duties including the accounting of cargoes and passengers at toll stations in northern Indiana located at Fort Wayne, Lagro, Logansport and Lafayette.

During those final years, neighbors along the canal had tired of the old ditch, blaming the canal for all sorts of reasons real or imagined. Among those accusations were fever emanating from canal water, occasional inadequate water supply, decaying structures, overwhelming debt, crop-field flooding, the inconvenience of roadways interrupted by canal waters, as well as a growing public agitation for ever-improving railroad technology.

Not surprising one night a disgruntled citizen cut a ditch through the canal towpath. That meant the water in the canal channel between the lift locks drained away putting a stop to navigation. Such vandalism was the reason Martin lost her two boats – one at the Carrollton lock near Delphi and another at Logansport. After an interesting career as a canal boat master, Mary Ann Hassett Martin died in September 1914 at the age of seventy-two and was laid to rest beside her husband Patrick in the Catholic Cemetery at Logansport, Indiana.

###

“Mary Hassett Martin – Canal Boat Captain” is from an article that appeared in Fort Wayne Monthly magazine. Allen County Historian Tom Castaldi is author of the Wabash & Erie Canal Notebook series; hosts “On the Heritage Trail,” broadcasts on WBOI, 89.1 FM; and “Historia Nostra” heard on Redeemer Radio 106.3 FM. and 95.7 F.M. His previously published columns may be found on the History Center’s blog “Our Stories” at historycenterfw.blogspot.com.

Questions & Answers

The Tumble provides an opportunity for our readers to ask questions about canals and obtain more information. Email your questions to Indcanal@aol.com.

Linda Castaldi—Fort Wayne, IN

Q-Most of what we read and hear about canal life is about the men who were officials or who built and operated the various canals. Did women play any role in Indiana’s canals?

A-The 19th Century was still a male dominated society and canal life was extremely male dominated. Most canal workers were unmarried males 17-35 years of age. They worked and played hard and often died young. The canal camps and shanty towns moved along as construction proceeded. Play time consisted of drinking, fighting and gambling. Most locals were glad to see these workers move out of their communities.

Even in this rough and tumble environment some women were found. Most were wives or children of some of the older workers. After the 1840s more families with children appeared along the work camps. Although contractors usually provided the men with wooden dormitory housing, tools and food on a construction site, married workers had to construct their own housing. In these homes women performed all the duties as would any housewife including managing the children. Women sometimes found employment with the contractor as a cook, laundress or seamstress. Wages were always about 50% less than males even when males worked as cooks. In the camps privacy was at a minimum. In nearby larger communities there were always certain types of women available to meet a young man’s needs. Refined ladies were not found in shanty towns along the canal.

Once canals became operational and boats were running a boat Captain might bring his entire family on the boat. His wife became the cook and could also steer the boat. Males handled the mules and young boys or family members became hoggees (mule drivers) on the towpath. At the locks, women sometimes operated the balance beams to open and close the lock gates. They also worked at various stops along the way where refreshments were served. Female entertainers found jobs on show boats that passed from town to town via the canal.

Although women played a behind the scenes role in canal times, they were very essential in support of themselves or at least in supplementing the income of canal workers or boatmen. Later these women became involved in the temperance and women’s rights movement that swept the country in the late 1800s.

Sue Simerman – Ossian, IN

Q-We often hear that canal construction workers worked hard and didn’t receive much compensation. How were canal workers paid and how did their compensation compare to other canal operatives?

A-Canal construction workers were paid via a signed contract to receive a monthly wage that varied throughout the 1830s-50s depending on the supply and demand for labor. The wage was also dependent on the economic conditions at the time. These wages ranged between $10-20 dollars per month. Pay was also impacted by the workers skill with carpenters and stone masons being higher skilled versus diggers and grubbers. In addition workers were provided with food and lodging. Food was usually prepared by a contractor paid cook and lodging was usually a wooden shanty that could sleep 10-15 workers. The contractors provided the worker with tools and sometimes clothing. Regardless, these were not luxury conditions. Considering the benefits provided, canal work outdoors was often better than work that could be obtained in the cities or on farms. Supply of workers was better in eastern markets producing lower wages there. Economic conditions such as the depression of 1837-39), drastically drove down the cost of labor with the abundant unemployed.

Comparison with other occupations were as follows: Chief Engineer Jesse Williams $1,800 per year in 1832, Resident Engineer $1500 per yr / Clerk $500 per yr / Toll Collectors – $15 -$40 per month / Rod man $10 per month / Boat Captain $50-100 per month Even pay for these jobs varied widely depending on location, responsibility and activity on certain sections of the canal.

For the best source of information about wages and life of the canal worker, I suggest you read Common Labor by Peter Way / 1993 Cambridge University Press

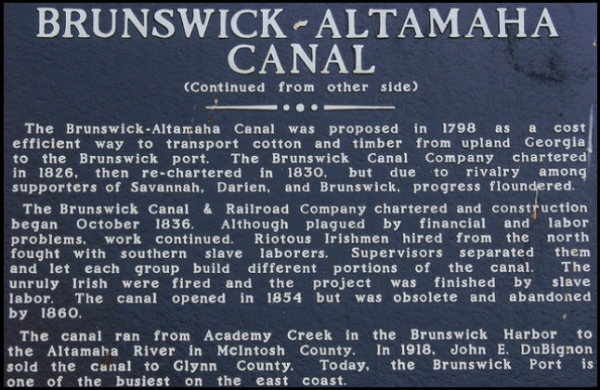

Did You Know That Slaves Constructed A Canal?

By Phyllis Mattheis

We canal people are always on the lookout for the next canal to investigate. There is one in Brunswick, GA that was constructed mostly by black slave labor. Brunswick was founded in 1771 on the Atlantic coast near St. Simons Island about an hour north of Jacksonville, FL and has a great natural shipping harbor, even today, but was not on an inland river.

We canal people are always on the lookout for the next canal to investigate. There is one in Brunswick, GA that was constructed mostly by black slave labor. Brunswick was founded in 1771 on the Atlantic coast near St. Simons Island about an hour north of Jacksonville, FL and has a great natural shipping harbor, even today, but was not on an inland river.

Because rivers were important arteries for conveying cotton and rice to ports, Darien, just north of Brunswick and located on the Altamaha River, became a major port for Atlantic shipping. So, in order to connect the two towns, a 12 mile canal construction began in 1836, the same year that Cambridge City was founded at the head of Indiana’s Whitewater Canal. In the beginning slave labor was contracted from local plantations, but Irish immigrants finally finished the canal over the next 18 years. What a long time to build such a short canal!

As we know, railroads were constructed in the 1850s and operated year round through night and day. So, this Brunswick-Altamaha Canal was never used, but the ditch with water can still be seen from a few of Brunswick’s streets, some of which have canal signs beside them. And a new shopping center called Canal Crossing is opening this year with the usual big box stores. Time marches on.

The Canal That Never Came To Be

By Gary A. Schlueter

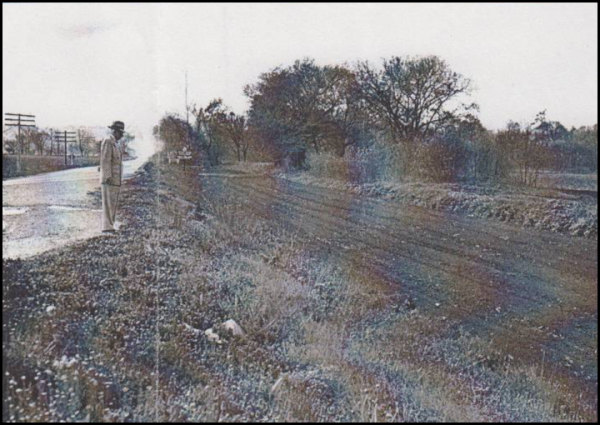

When James M. Miller wrote his report on the Richmond and Brookville Canal for the Indiana Quarterly Magazine of History in 1905 he said one could still find traces of the “almost obliterated…old canal ditch upon which no small labor was once expended.”

Unlike the Whitewater Canal the funding for the Richmond and Brookville Canal did not come from the internal improvement act of 1836. Miller reports that it seems to have been taken up by the State of Indiana as an afterthought to connect Richmond and the East Fork of the Whitewater with the more prominent canal which follows the wilder West Fork.

Miller, a Brookville native, noted that the first settlers along the East Fork were “thrifty, energetic people” who soon created surpluses which they would send along rivers to New Orleans. These surpluses were sent on flatboats built in Dunlapsville and Quakertown.

By 1834 the scheme for the R&B Canal was afloat, so to speak. The first delegation which assembled at Dunlapsville on September 12, 1836 consisted of 13 delegates from Richmond, seven from Abington, 10 from Brownsville, seven from Dunlapsville, two from Fairfield (RIP), and seven from Brookville. Oddly enough there is no mention of any from Liberty where a post office had been in operation since 1824.

In the summer of 1837 the way was surveyed and local engineers then working on the Whitewater Canal were employed so as “to incur no extra expense to the State.” As surveyed the canal was 33 miles long and 26 feet wide on the bottom and 40 feet wide on the surface and to have a depth of four feet of water.

Because there was to be a fall of 273 feet along the way two guard locks, two aqueducts, seven culverts, two water weirs, 16 road bridges, two towpath bridges, five dams and 31 lift locks would be needed. The canal was estimated to cost $15,277 per mile which meant, including contingencies, the cost was to be $507,966.

In his survey report Colonel Torbet wrote, “It would be the channel through which all the trade of one of the most populous, fertile and wealthy regions of the western country would pass. Richmond, situated at the head of navigation, with its vast water power, extensive capital, and enterprising inhabitants, might become the Pittsburg of Indiana.”

The company began to sell stock on April 1, 1839 in Richmond, Abington, Brownsville, Dunlapsville, Fairfield and Brookville. By April 27th the company had sold $215,000 worth of stock, according to a report in the Richmond Palladium.

Bids were let for construction sections in September 1839 and specifications were posted in Dr. Matchett’s tavern in Abington, Dr. Mulford’s tavern in Brownsville, Abijah DuBois’ tavern in Fairfield and D. Hoffman’s tavern in Brookville and at the company’s office in safe and sober Richmond.

All the sections were let except the steepest one near Brookville. One and a half miles were excavated near Hanna’s Creek and another mile or two near Richmond. Then the process seems to have died. Miller reported, “No use of these excavated portions were ever made until 1860 when Leroy Larsh erected a grist mill on the portion near Richmond, which is yet (1905) in operation.”

He concludes, “Richmond failed to become the Pittsburg of Indiana.”

Courtesy of the Whitewater Valley Guide Vol. 6 No. 28 Issue 289, garyschlueter@gmail.com

Whitewater Canal Trail Workers

On Saturday February 25, 2017 warmly dressed members of the Whitewater Canal Trail met in the morning to work on the trail at U.S. 52 and Gooseneck Road in Metamora, Indiana. The men brought chain saws to remove limbs and picked up fallen debris. The women wore gloves to drag the debris to the burn pile. Good progress was made on getting the trail ready for Spring during the three hour period.

On Saturday February 25, 2017 warmly dressed members of the Whitewater Canal Trail met in the morning to work on the trail at U.S. 52 and Gooseneck Road in Metamora, Indiana. The men brought chain saws to remove limbs and picked up fallen debris. The women wore gloves to drag the debris to the burn pile. Good progress was made on getting the trail ready for Spring during the three hour period.

The trail workers have worked several more times in February and March since this picture was taken. On good Saturdays they have cleaned up more brush and removed trees while enjoying camaraderie.

Canal Boat Arrives in Ft. Wayne

Friends of the Rivers organization announced the arrival of a canal boat replica to be used on Fort Wayne’s three rivers on Thursday, March 23, 2017. The 54 feet long and 11 feet wide boat can take up to 40 people on discovery or educational cruises, 20 people on a dinner cruise or be chartered for parties. It was built in six months by Scarano Boat Building of Albany, New York and basically patterned after Delphi’s canal boat. Unlike Delphi’s electric motors, this new boat will be powered by 55-horsepower diesel engines. Its hull is aluminum with a wooden superstructure.

The Community Foundation of Greater Fort Wayne helped raise funds for the $550,000 replica (before modifications). The AWS Foundation helped with funds and expertise to make is handicap accessible.

Cruises are scheduled to begin on June 1. Reservations and trips will be booked through Fort Wayne Outfitters. Although the boat can travel about 8 miles on Ft. Wayne rivers —as far north as the Johnny Appleseed Park dam on the St. Joseph River, as far east as the Hosey Dam on the Maumee River and as far south as north of Foster Park on the St. Marys River—normal tours will be limited to 90 minutes and travel a portion of the miles available. It will cruise at 2-3 mph. It will be temporarily docked at Headwaters Park West. Students will vote on a name for the new boat.

McCain Speaks to ARCH about W & E Canal

On Saturday March 25, 2017 at 11 A.M., Dan McCain, President of Carroll County Wabash & Erie Canal Association and CSI director, spoke to members of A.R.C.H. at the downtown Ft. Wayne Allen County Public Library. He talked about how volunteers in Delphi have built Canal Park and how people in Ft. Wayne could do the same. He gave some history of the Wabash & Erie Canal saying it all started in Ft. Wayne. CSI members in attendance were Tom Castaldi, Bob & Carolyn Schmidt, and Steve & Sue Simerman. Bob Schmidt, CSI president, handed out CSI brochures.

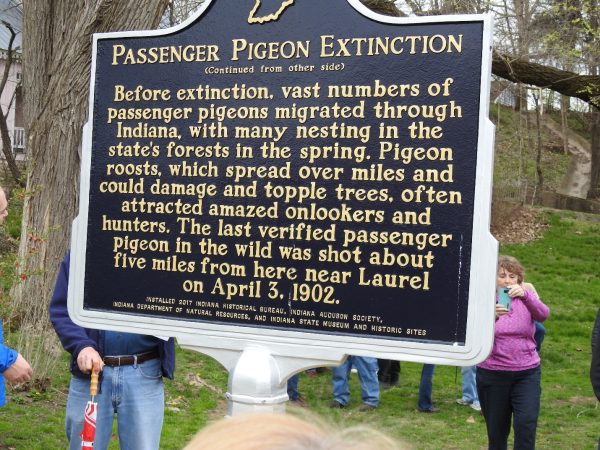

Passenger Pigeon Marker Unveiled

A public dedication ceremony for an Indiana state historical marker commemorating the Passenger Pigeon in Indiana was held on Monday, April 3, 2017 at 1 p.m. in Gazebo Park at the Whitewater Canal State Historic Site, 19083 Clayborn St., in Metamora, Indiana. April 3rd marked the 115th anniversary since a male pigeon was shot near Laurel, Franklin County. This is the last verified Passenger Pigeon to have been collected from the wild.

A public dedication ceremony for an Indiana state historical marker commemorating the Passenger Pigeon in Indiana was held on Monday, April 3, 2017 at 1 p.m. in Gazebo Park at the Whitewater Canal State Historic Site, 19083 Clayborn St., in Metamora, Indiana. April 3rd marked the 115th anniversary since a male pigeon was shot near Laurel, Franklin County. This is the last verified Passenger Pigeon to have been collected from the wild.

The Canal Society of Indiana contributed $100 toward this marker. The feeder dam and feeder canal for the Whitewater Canal is located in Laurel, Indiana. It is highly likely that passenger pigeons once lived in the area around the canal.

Passenger Pigeon Historical Marker Dedicated at Metamora

By Cynthia Powers

On April 3 my husband and I journeyed to Metamora, Indiana to witness the dedication of an Indiana State Historical Marker commemorating a tragic event: the last wild Passenger Pigeon was shot nearby at Laurel, Indiana. The marker was placed at the Metamora canal site so more people can see it.

On April 3 my husband and I journeyed to Metamora, Indiana to witness the dedication of an Indiana State Historical Marker commemorating a tragic event: the last wild Passenger Pigeon was shot nearby at Laurel, Indiana. The marker was placed at the Metamora canal site so more people can see it.

Addressing the crowd were Michael Homoya of the DNR, Casey Pfeiffer of the Indiana Historical Bureau, Jeff Canada, President of Indiana Audubon Society, and Joel Greenberg, author of A Feathered River Across the Sky—the Passenger Pigeon’s Flight to Extinction. Joel’s research documented the facts stated on the marker.

Although the speeches first referred to the “taking” of the bird, the fact remains that it was shot, and the text of the marker says that. This happened exactly 115 years ago, on April 3, 1902. The corpse was shown to Amos Butler, of Indiana Audubon Society, and therefore confirmed. Later it was stored in a leaky attic, resulting in its loss to science.

Although the speeches first referred to the “taking” of the bird, the fact remains that it was shot, and the text of the marker says that. This happened exactly 115 years ago, on April 3, 1902. The corpse was shown to Amos Butler, of Indiana Audubon Society, and therefore confirmed. Later it was stored in a leaky attic, resulting in its loss to science.

The whole episode, like the more recent shootings of whooping cranes in Indiana, is not something our state should be proud of. However, I’m glad it is not forgotten. Over half the funds for the marker were raised by a GoFundMe account set up by Indiana Audubon, to which the Canal Society contributed.

No more extinctions!

Domestics in Delphi: Backstairs at the Case House

By Mark Smith

The following presentation is precipitated by a move by Annadell Lamb and the Case House Committee to retrofit the back room at the Case House, which is presently being used for artifact display, back to its original purpose, which was that of a hired girl, or, to use a more diplomatic term, “domestic”.

In capriciously researching the person of Reed Case on Ancestry.com, I observed the 1850 census showed a person who was not a member of the family living with them at that time whose name was Louisa Lawyer. I surmised that this person was a domestic hired by the Case family and who inhabited the quarters now under discussion. This led to a more developed research project, which I hope will aid in interpreting the entire domestic scenario of that energy-charged vital time period known as the “Canal Era” in the Delphi area, which was approximately from the years 1840 (date of the canal’s entry into Delphi) to 1874 (date of the canal’s cessation of operations due to financial issues and other pressing matters.

In capriciously researching the person of Reed Case on Ancestry.com, I observed the 1850 census showed a person who was not a member of the family living with them at that time whose name was Louisa Lawyer. I surmised that this person was a domestic hired by the Case family and who inhabited the quarters now under discussion. This led to a more developed research project, which I hope will aid in interpreting the entire domestic scenario of that energy-charged vital time period known as the “Canal Era” in the Delphi area, which was approximately from the years 1840 (date of the canal’s entry into Delphi) to 1874 (date of the canal’s cessation of operations due to financial issues and other pressing matters.

I then proceeded to investigate further the role of domestics in the Case family, and I discovered that in the 1860 census (post-Front Street move), there was an Ellen Saday, from Ireland living with the Case family, which had then moved to another home on Front Street after daughter Josephine’s marriage to Bernard Schermerhorn, who also employed an Irish domestic whose name was Catherine Madden. Bridget Carey was another young maid from the Emerald Isle, who was a regular part of the Case House retinue, as was a Fanny Burgess, of uncertain nationality. Although the Case family’s move from the Front Street address had long passed there seemed to have been a pattern of the Case family employing domestics to serve their family.

I might add a note here about the various changes of residences of the Case family. According to the National Register writing about the Case home at 312 E. Main, following daughter Josephine’s marriage to Bernard Schermerhorn in 1858, father Reed changed residences again to another site on Front Street.

I might add a note here about the various changes of residences of the Case family. According to the National Register writing about the Case home at 312 E. Main, following daughter Josephine’s marriage to Bernard Schermerhorn in 1858, father Reed changed residences again to another site on Front Street.

Other merchants who followed the pattern of Irish lassies to do their household duties were Vine Holt, entrepreneur and merchant, whose Hibernian domestic was Johanne Hogeland; James Dugan, whose domestic was Ann Ryan, (another was Catherine Fose, of uncertain nationality); Scots paper miller George Robertson, whose “hired girl” was one Margaret Quinn; James Hervey Stewart, historian, founder of the Old Settlers Association, and Clerk of the County, whose domestic was Alice Huss; Shoemaker John Burr, whose residence was coincidentally adjacent to the Case family on E. Main, whose domestic was Margaret Ryan (relative of Ann?); and James Ralston Blanchard, also a part of the Front Street Canal milieu, whose domestic Bridget Stankard was also from the Emerald Isle.

Continuing with the Celtic motif, noted author Sarah Smith Pratt recounts in her article in the Thursday, October thirteenth, 1938 that “Irish Catholics began to migrate (due to grievances against Queen Victoria). The Wabash Erie Canal was under construction. Irish laborers came to Delphi and settled together in the northern end of town—the Ryans, Shealys, Burkes, Burns, Dalys, and others. Barney Daly became a prominent lawyer. A number of Irish girls were sent over to marry these men as was the custom in colonial times. I remember that these girls were assembled in the Delphi House and there Delphi ladies went to hire these girls. My mother, Mrs. Smith, Mrs. Reed Case, Mrs. Dugan, Mrs. Bowen, and others went to select household workers. These girls proved very loyal. Nora Trebley from County Cork lived with us for many years and married from our house. I walked with her at her funeral at Logansport not so many years ago.” These Irish Roman Catholics must have been in the minority due to Dora Thomas Mayhill’s statement on p.44 (Old Wabash and Erie Canal) that the majority of workers were Protestants.

Ironically enough, there were other notables such as Citizen’s Bank entrepreneur Erastus Hubbard and Daniel McCain who were evidently self-sufficient enough and whose census of 1870 didn’t reflect any such extraneous members of the household. In the census of 1850 Abner Hunt Bowen, noted banker of East Main, showed a Lucinda Doolittle, who could have been a domestic but whose name was not accompanied by an indicative job title of domestic.

Domestics from the Emerald Isle fairly well dominated the scene, according to Faye E. Dudden in her book Serving Women: Household Service in Nineteenth-Century America (Wesleyan University Press, Middletown, Connecticut). Indeed, “When the Society for the Encouragement of Faithful Domestic Servants began to run its placement service in New York City in 1825, 60 percent of the applicants were Irish (p. 60). Carol Groneman speculates that Irish families may have chosen to send daughters rather than sons to the New World precisely because daughters were more assured of finding employment and more faithful in sending remittances home. (ibid), p. 61. Thus it seems as if the Delphi Domestic scene fairly well reflected the nationwide norm of employing young Colleens to do their bidding in the home.

The social climate of Delphi seemed to have been more accepting of these Irish ladies than that of the nation because of religious prejudice mainly directed toward the Roman Catholic element, depicting the Roman Catholics as mistrusted, spies of the Pope, and sent to brainwash members of the household. (Americans and Their Servants; Domestic Service in the United States from 1800 to 1920, Daniel E. Sutherland. Louisiana State University Press; Baton Rouge and London, p. 39.

Although this may not apply to the Delphi scene, typical duties involved making candles and soap, spinning wool and dyeing yarn, and performing all the other housework. (Faye Dudden, p. 35). Other duties were emptying chamber pots, changing infants, cleaning up after pets and those with weak bladders and upset stomachs. Some were even expected to be well-versed in cleaning blueberry stains from linen. (Sutherland).

We now return to the room in question—that of the Reed Case House, which is soon to be re-purposed to its original function-that of housing Louisa Lawyer, the resident domestic for the Case family.

“Employers shielded themselves from the daily comings and goings of servants too. Servants, for instance, always entered and left the house through a service entrance which was usually at the rear or side of the house; although in many townhouses it was located beneath the front stoop. In any case, it opened into the kitchen or an adjacent hallway, thus lessening the family’s risk of undesired encounters. Employers also designated back stairs for servants’ use. These were not found in the average townhouse before 1850, but thereafter, the growing size of American houses and the need for privacy made them indispensable. At the very bottom or the very top of back stairways one found servant’s living quarters.”— (Sutherland).

VOLUNTEERS WORK AT CANAL PARK

By Dan McCain

Volunteers are the most essential part in the construction and maintenance of Canal Park in Delphi, Indiana. January found them outside the Wabash & Erie Canal Interpretive Center cutting down infected Emerald Ash Borer trees, sawing them into firewood length pieces and giving them for “Free” to several cutters who helped with the project.

Volunteers are the most essential part in the construction and maintenance of Canal Park in Delphi, Indiana. January found them outside the Wabash & Erie Canal Interpretive Center cutting down infected Emerald Ash Borer trees, sawing them into firewood length pieces and giving them for “Free” to several cutters who helped with the project.

On bad days the Monday-Wednesday-Friday volunteers worked indoors on the model of the watered canal, which had a perennial leak causing the floor to stay wet. They repaired it and the model lock gates which had an accumulation of calcium on them. They will also repaint the entire model to look like new. This is a premier model for any canal museum in the U.S.

Work is underway on the Blacksmith Shop being built in Canal Park. It must be finished by June 30, 2017 to meet the grant requirements of the Tippecanoe Arts Federation utilizing North Central Health Services money.

Work is underway on the Blacksmith Shop being built in Canal Park. It must be finished by June 30, 2017 to meet the grant requirements of the Tippecanoe Arts Federation utilizing North Central Health Services money.

The “Old Sleeth Post Office,” a 10 x 15 foot building which previously has been moved twice to two places in White County, has been given to Canal Park by the Antique Tractor Club and moved by Rollin Graybill to a temporary spot in Canal Park where repairs will be made. Its eventual home will be across the Wabash & Erie Canal near the recent placement of the restored Lutheran Church.

The “Old Sleeth Post Office,” a 10 x 15 foot building which previously has been moved twice to two places in White County, has been given to Canal Park by the Antique Tractor Club and moved by Rollin Graybill to a temporary spot in Canal Park where repairs will be made. Its eventual home will be across the Wabash & Erie Canal near the recent placement of the restored Lutheran Church.

Grants from the Carroll County Community Foundation from Kokomo and a matching grant from the Canal Society of Indiana are making possible another operating model in the Canal Museum. It will feature a model railroad with a steam engine “running circles around a canal boat” as was the common thinking in the 1870s. At that time railroads had become established and their speed far exceeded the pace of canal boats. Ron Burkhardt (standing) and his crew are planning this exhibit.

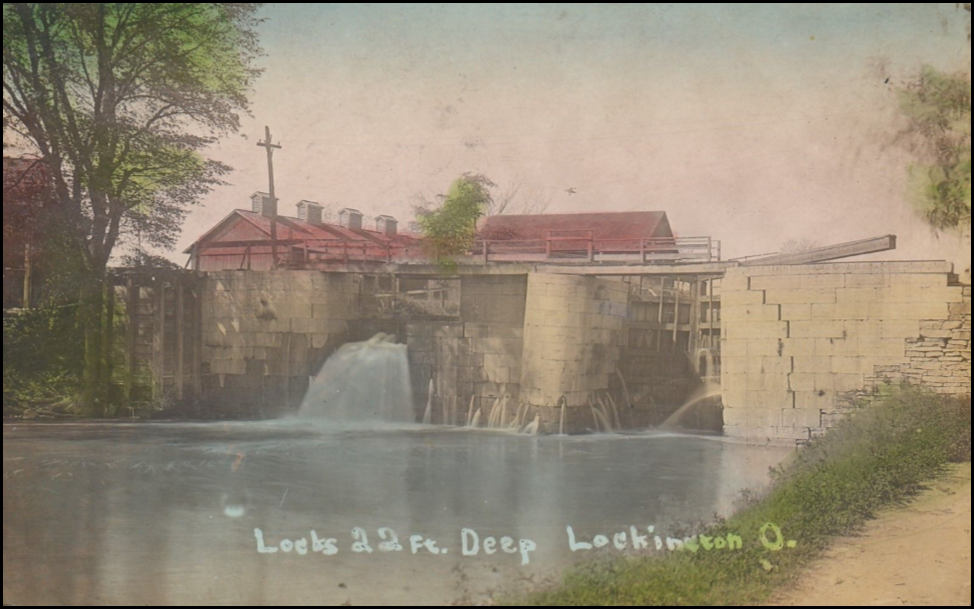

Lockington Locks on the Miami & Erie Canal

The LOCKINGTON LOCKS, a series of six locks which were built between 1837 and 1845, raised and lowered canal boats a total of 67 feet in about a half of a mile. The upper lock, near the “Loramie Summit,” is the high point between Cincinnati and Toledo on the Miami and Erie Canal. These locks were vital to transportation and water supply in the mid nineteenth century.

The locks are located at the southern end of the Loramie Summit, which stretches 21 miles from Lockington north to New Bremen. They were constructed of large limestone blocks weighing as much as 500 pounds. Their floors were wooden. Their gates were made of white oak. To overcome the 67 foot elevation, Lock 48 had a lift of 10 feet Lock 49, 11 feet; Lock 50, 11 feet; Lock 51, 11 feet; Lock 52, 12 feet; and Lock 53, 12 feet. Today the locks are numbered coming off the Summit. “Big Lock” or Lock #1 is at the top as the locks descend southward.

Boats would typically take several hours to pass through the locks; as a result, the village of Lockington (originally named “Locksport”) was founded to provide services to idle boatsmen and passengers. It was a leading point on the canal. Besides the locks, the village was the site of the junction of the canal with Loramie Creek, which was originally spanned with an aqueduct. The village lay at the end of a feeder line that brought large amounts of water from the Lewistown Reservoir in nearby Logan County. This small feeder canal was designed to meet the main line at Lockington because the Summit included the canal’s highest elevation of 944 feet above sea level.

The high point of Ohio’s canal system was reached in 1855. After that year, revenues fell steadily due to competition from railroads. Then the canal’s primary source of revenue came from water sales. Restorations were attempted in the 1900s, but all attempts at refurbishing the system ended after a disastrous 1913 flood that destroyed many of the canal’s components and ended all hopes of its future commercial use.

In 1969, the Lockington Locks were listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The locks qualified for inclusion on the Register both as an important engineering accomplishment and because of their place in the area’s history.

At the high point of this series of locks is “Big Lock.” Made of limestone quarried in nearby Dayton it is one of the better known locks in the state. In the 1970s wooden supports were added to stabilize the structure and keep it from collapsing. Photos taken by Dave Olsen show an attempt to stabilize the lock.

What started to be a short term of stabilization ended up covering several decades as the locks deteriorated. After years of planning and more than a year’s worth of labor, the Ohio History Connection unveiled the complete restoration of historic Lock 1 South in Lockington during a rededication ceremony Thursday, August 21, 2014 at 4 p.m.

The project included the complete dismantling of Lock #1, installation of a concrete mat footing, reconstruction of the walls, and grading. Each stone in the entire structure was numbered as it was taken apart so it could be put back in the original position. Only 50 stones were replaced and 100 repaired in this massive project.

The Ohio History Connection saw the project through completion, along with the Ohio Department of Transportation, the Village of Lockington, Spieker, Inc., McMullen Associates and DGL Consulting Engineers. Funding came from a Transportation Alternative Grant of $1,900,000 and matching funds from the State of Ohio totaling $899,534.

Today, Lockington Locks and the surrounding land are a park. The only water that flows through the locks is runoff from heavy rains. The site’s other remains include the abutments of the aqueduct as well as the dry-lock basin and lockmaster’s home.

Directions:I-75 exit 82 (US Hwy 36) west into Piqua. Turn north on Main St. Cross the Great Miami River and turn left (northwest) on Piqua-Lockington Rd/CR-199 (At the Shelby County line its name changes to Miami Conservancy Rd). Continue north 4 mi. Lockington. Turn left (west) onto Museum Trail. The locks are two blocks ahead on the south side of the street, in the center of town.

The Canal Society of Indiana is planning to visit the Lockington Locks on its fall tour in 2018.

Tumbles Devised by Ohio Canal Engineers

By Terry K. Woods

I read your article on TUMBLES in the last issue of The Tumble. I’m of the school that believes they were first devised by Ohio Canal engineers in 1827. The northern division of that canal had begun operation on July 4th 1827. All that section used Erie Design Lock Culverts to pass water. After 1827 that section was to be changed to Regulating Channels and Weirs (Bypasses and Tumbles).

Any new sections were built including them. In my research I have found that the terms Weir and Sluice were the two most overworked terms in the lexicon of canal-speak.

Nearly anything that could pass water, including locks, were termed a Sluice at one time or another. A Weir, I believe, was originally the small dam and cut-out that was used to calculate water flow. Later, anything that looked like a weir was called one.

I enjoyed the story of Howe’s letter to Leander Ransom. My research indicates that the Ohio Canal Commissioners tried to use the Lancaster Ohio Bank to distribute their funds whenever possible. That period in Ohio from 1837 into the early 40s was a hell-hole of ‘funny money.’ For years no paper money was trusted in the ‘west’ and “barter” ruled commerce.

In the above article the author made reference to the “15 locks that are now part of Cascades Locks Park”. Cascades Locks Park begins at Market street (between locks 8 and 9) and goes to Mustill’s store at Lock 15. No lock in that area can really be discerned until maybe 11. Even so,attempts in the 30s and 50s to turn the canal into a storm sewer have disguised most of the remaining structures in that area, except locks 14 and 15, quite well.

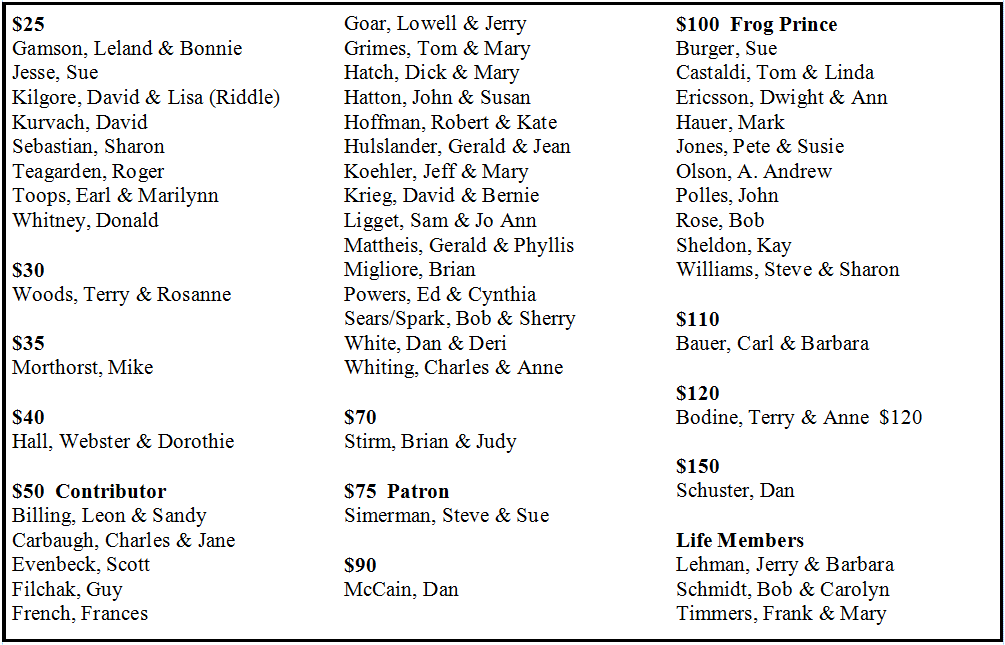

DONATIONS TO CSI

The following Canal Society of Indiana members have donated over the $20 single/family membership rate to support the organization’s projects.

Member Milestones

The Canal Society of Indiana congratulates the following members:

Ernie Ellis of Hillsboro, Indiana turned 100 years old on February 26, 2017. His birthday celebration was held at the Myers Dinner Theater in Hillsboro from 2-4 p.m. on February 25th.

Ellsworth Smith, CSI director from Leo, Indiana was selected as a winner of the Outstanding Arts Advocate award from Arts United of Fort Wayne. Ellsworth, Robert Nickerson and Bill Zabell were founders of The Embassy. These three engineers were integral in saving the Grande Page Organ and the Embassy Theatre. The Historic Embassy first opened on May 14, 1926. It now features national productions from the Broadway stage, concerts of all musical formats, cinema and educational programming. It is on the National Register of Historic Places.