Index:

Panama Grit & Glory

By Bob and Carolyn Schmidt

On Tuesday morning by 6:30 A.M. our group lined up anticipating an exciting day through the Panama Canal. Our bus, the Portabella, left at 7 A.M. for our port of departure. Our boat was docked alongside another tourist boat, “Tuira” pronounced “Twe a’,” which later followed close beside our boat to the first lock and was in the first lock with us. We boarded our boat, the “Islamorada,” which once was owned by Al Capone and used to run rum in the 1920s. It had been refitted to carry about 50 tourists plus staff. We were welcomed by the docent on board and learned that the toll for our boat was to be about $2,000. We set off to meet our Panama Canal pilot.

The Canal Authority has about 50 tugboats to move the pilots and ships through the canal. Soon one of these tugs pulled up alongside our boat and our pilot hopped onboard. After communication with the tower we headed for the Miraflores locks.

In the distance on our right was a great view of the new Panama City. Nearer to us was the Port of Balboa, where huge cranes loaded and unloaded cargo. Soon we passed by our hotel, Country Inn and Suites, and then beneath the Bridge of the Americas.

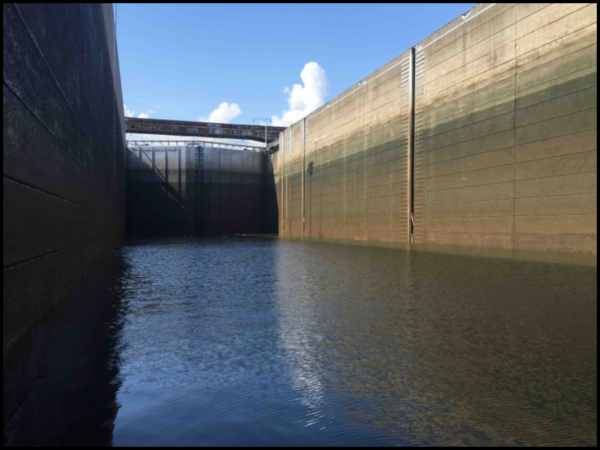

As we approached the first set of locks we were lined up behind the LP Gas tanker, “Bow Star.” We were told that a small boat always follows the larger ship when heading toward Gatun Lake, but the smaller ship is in front of the larger ship when it exits the lake. Just as the “Bow Star” entered the first lock, we thought we would follow it into the lock, but, to our relief, we were switched to the adjacent lock by the Canal Authority. We had to wait for a southbound ship to clear the lock. The “Tanja,” a dry bulk shipper under a Liberian flag, was coming up behind us. We waited for it to enter the Miraflores Lock and then our boat and the “Tuira” followed her in. We were tethered up by one of the crew tossing a rope to a lock hand above. This lock was very full with the “Tanja” in front and the “Islamorada” and “Tuira” tied side by side in back of it.

The Miraflores locks are composed of two steps of side-by-side locks that we had viewed the day before from the visitor center. The gates on this original lock close in a V shape just as in our old canals. At the upper end of the lock double gates were built to protect the lock in case a ship crashed through one set.

Inside the lock we were very close to the walls covered with green slimy algae and could examine the electric mules that kept the large ship in the center of the lock. We were tied so close to the “Tuira” that a Panamanian lady reached across the two boats’ railings to offer hats, magnets, T-shirts, bags and key rings for sale. As some of our people were starving to shop she did a brisk business.

Inside the lock we were very close to the walls covered with green slimy algae and could examine the electric mules that kept the large ship in the center of the lock. We were tied so close to the “Tuira” that a Panamanian lady reached across the two boats’ railings to offer hats, magnets, T-shirts, bags and key rings for sale. As some of our people were starving to shop she did a brisk business.

After being raised about 54 feet through the two lock chambers we proceeded toward the Pedro Miguel locks. This last set of side-by-side locks had to be built separate from the Milaflores locks due to a fault line. We passed through the chamber at Pedro Miguel and were raised about 31 feet to reach Gatun Lake.

Just after leaving Pedro Miguel, we passed under the 3,451 foot Centennial Bridge, which rises 252 feet above the center of the canal. The style is similar to the Revenal Bridge at Charleston, S.C. over the Cooper River.

Just after leaving Pedro Miguel, we passed under the 3,451 foot Centennial Bridge, which rises 252 feet above the center of the canal. The style is similar to the Revenal Bridge at Charleston, S.C. over the Cooper River.

The channel began to narrow as we entered the infamous Calebra Cut. Before Panama took over the canal in 2000, this cut was called the Gaillard Cut after David Gaillard, the Chief Engineer in this area. This 8-mile-stretch was the most difficult portion of the canal to construct. Here the French, and later American, dream of a sea level cut died. The deeper the cut was made the more landslides occurred and the cut had to be continually widen. Today, the channel is still being excavated to handle two way traffic of the Neo-Panamax vessels. Terraces have been built along the route that should reduce the magnitude of any future landslides. We again saw the dredging equipment in operation near Gamboa. The rock that was dredged was put on barges and the soil was carried through pipes to fill in swampy areas.

We had a change of pilots as we entered the open waters of Gatun Lake. Our new pilot turned up the speed once we cleared the cut. We discovered later that he was trying to get us to enter Gatun Lake ahead of other ships so that our wait time could be considerably reduced on the other side of the lake. We asked our guide Archie when our boat would arrive in Colon. His answer was “it depends. It could be as late as 7:00 at night.”

We reached the Gatun Locks, entered before a huge vessel and descended the 85 feet through three lock chambers to reach the Caribbean about 5:30 P.M. thanks to our pilot, who then left our boat via a tug.

As we proceeded to the dock in Colon we saw the 3rd bridge that the Panamanian government is building over the canal and is planned to open in 2018. We finally arrived at the Free Trade Zone where goods can be stored and transferred duty free. This trade zone is 2nd only to Hong Kong. After walking through one of the buildings we boarded our bus to head to the hotel.

Our hotel, Melia Panama Canal, which was built in the mid-1940s as part of the School of the Americas, was once used for jungle training purposes and trained such dictators as Osama bin Laden and Manuel Noriega. It then became Ft. Gulick Hospital. Today the rooms are completely refurbished. It has beautiful swimming pools and a canoe landing on Gatun Lake. There we had a great dinner buffet and morning breakfast.

On Wednesday we explored Colon by bus. Nearby we saw housing used by American canal workers. We passed by Hope Cemetery where many of the “silver,” black workers, were buried. This place was originally called Monkey Hill because of the huge population of monkeys living there.

Our main event for the morning was seeing and learning about the Neo-Panamax locks, Agua Clara, which are located on the east side of Lake Gatun. These locks are easily accessible by road versus the Neo-Panamax locks, Cocoli, which are on the west side alongside the Miraflores locks. A beautiful overlook, gift shop and theater with a video about the locks have been built.

As we overlooked the new locks a LP gas ship, “Leto Providence,” was just being towed by the tugs into the first lock from the Caribbean. With its highly explosive cargo, precautions were taken and the ship just crept into the lock for about 1 hour. This is what most of us had come to see and we certainly were rewarded.

These new locks each have 3 levels of water saving basins for each lock chamber. Think of each lock chamber as being divided into 5 segments. To empty the lock the top 3 segments are drained into the 3 basins. This represents 60% of the lock’s water. To raise a ship the basins are directed back into the lock. Only 40% of the water in each lock is eventually lost into the Caribbean or Pacific oceans. The total locking process on the new locks uses 7% less total water than the old locks. The fresh water from the Chagres and then Gatun Lake eventually gets swept into the oceans. Even the filling of the locks from the basins seemed very slow. We had time to watch a video on lock operations. There was also excitement nearby when someone spotted a three-toed sloth in the trees by the overlook. Sloths also move very slowly. Their natural enemy is the Harpy Eagle, which can quickly snatch a sloth lumbering down a tree.

Back at the lock, the “Leto Providence” finally was in the first lock. Over on the western side, across a strip of land, a Princess cruise ship was moving through the old Gatun Locks. The lockage over there went much faster. In the new locks we observed the retractable lock gates that allow two way traffic to pass over them. The are hollow so they may be repaired from the inside and are in sets of two.

At 11:00 AM it was time to go back to our hotel for lunch. Just then the 2nd lock gates finally opened and the ship started to move into the second lock chamber. What a slow process.

Back at the Melia Panama Canal hotel a buffet lunch was served with beer for all. After a brief siesta Carolyn and I wandered about the grounds to see the wonderful swimming pools and boat launches.

Back at the Melia Panama Canal hotel a buffet lunch was served with beer for all. After a brief siesta Carolyn and I wandered about the grounds to see the wonderful swimming pools and boat launches.

At 3:30 P.M. our bus headed to the Panama Railroad for our trip back to Panama City. We hustled aboard to get the only observation coach. Although this railroad was originally built from 1850-1855, much of the original route had to be rerouted during the time of the American canal building. The original route had followed the Chagres River valley, which was flooded for Lake Gatun. Today this railroad is owned by the Kansas & Southern Railroad in the U.S. The train ride was very smooth and we had an excellent view of Gatun Lake and the surroundings. The trip on the canal had taken a day while the 50-mile-long train trip back to our hotel at the other end of the canal took about an hour.

We were bussed to the Crown Plaza Hotel for our lodging and dinner. Our dining area was beside a gorgeous pool. We had a spectacular view of Panama City and a delightful buffet dinner with wine. After dinner Archie said he had a special surprise. A group of dancers —4 ladies and 4 men—dressed in Panamanian attire for celebrations and accompanied by a small band consisting of an accordionist, drummer, and maraca player entertained us with Panamanian dances. Archie explained their dress telling how both the women’s gowns and men’s shirts were hand-made and embroidered. He told us how the men could change their hat brims to show if they were available or not, etc. Kay Sheldon, CSI/CSO from Ohio, and another lady on the tour were presented a birthday cake and danced with the dancers. Our Panama Canal adventure had come to a close.

Thursday morning, after a quick breakfast in the hotel lobby, we went back to Tocumen Airport about 6:30 A.M. to return to the U.S.A. We all had a marvelous trip. We hope some of you will decide to visit Panama soon. For more detailed information about the Panama Canal we suggest you read The Path Between The Seas by David McCullough.

Thursday morning, after a quick breakfast in the hotel lobby, we went back to Tocumen Airport about 6:30 A.M. to return to the U.S.A. We all had a marvelous trip. We hope some of you will decide to visit Panama soon. For more detailed information about the Panama Canal we suggest you read The Path Between The Seas by David McCullough.

Photos by Bob Schmidt

Canawlers At Rest

NORMAN S. BROWN

May 18, 1811—June 8, 1886

Find-A-Grave #41412578

By Carolyn I. Schmidt

Norman S. Brown was born in Ellisburg, Jefferson county, New York, on May 18, 1811 to Avery and Laura McKee Brown, who were married on February 13, 1805. His father, Avery, was born in Stonington, Rhode Island on March 4, 1785 to Thomas Brown and drowned on September 14, 1811 in Pulaski, Oswego county, New York at age 25 when Norman was only four months old. His mother, Laura, was born on May 8, 1787 in Middlebury, Addison county Vermont to Joseph McKee Jr. (1758-1829) and Irene Marsh McKee (1765-1828). Norman lived with his mother and siblings, Laura A. Brown (1807-??) and Avery O. Brown (1809-??). His mother then married John C. Otis (1787-1870) on July 11, 1813.

In 1822 at age eleven Norman left home. When age fourteen in 1826 he apprenticed himself to the hatter’s trade, but at the end of two years his employer went out of business and he never finished it. He then became a cabin-boy on a steamboat on Lake Ontario, but he did not stay in this place long. The following winter he went to school. In the spring he was hired as a steward on an Erie Canal packet/passenger boat and after a time became a bowsman, a crew member whose duties included snubbing the boat to a stop in the lock or alongside a dock. Norman was on the Erie Canal from the fall of 1828 to the spring of 1831 when he went to Cleveland, Ohio to work on the Ohio & Erie Canal.

While working on the Ohio & Erie Norman met Maria E. Carter, of Summit county, Ohio. Maria, who was 17 years old, was born on May 30, 1815 in Ohio. Norman and Maria were married on January 6, 1833. On December 25, 1833 their first child, William A. was born. Then in December 27, 1835, Laura Amelia was born. She died in Attica in 1912. Their last child, Harley, was born January 13, 1838 and died in infancy.

Norman worked on the Ohio & Erie Canal from 1831 until 1844 except for the years 1837 and 1838. Those years he worked for a paper-mill and ran a livery stable.

In the spring of 1843 at age 32 Norman came to Indiana via the Wabash & Erie Canal. He must have liked what he found in Indiana for early during the following winter he came down the Wabash river on a keel-boat and arrived at Attica. At once he set up a grocery and dry goods trade, which he continued for fourteen years.

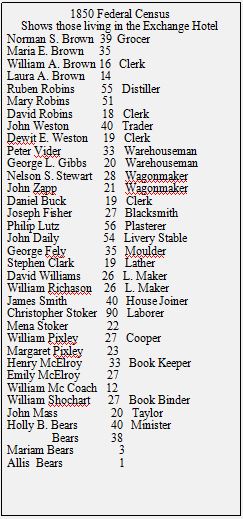

In 1849 and 1850 he was the inn keeper for the Exchange Hotel in Attica. Those residing in the hotel in 1850 can be seen on the Federal Census. From 1866 to 1877, he was an express agent. He owned a farm of 320 acres that was situated on the opposite side of the Wabash river. For over twenty-five years, he rented out the farm and then took over its cultivation.

At first Norman was associated with the Whig, and later the Republican, party. But he soon lost the strength of those ties and decided to vote “for the best man.”

1815-1894 1811-1886

Riverside Cemetery, Attica,

Fountain County, Indiana

Norman S. Brown passed away on June 8, 1886. He was laid to rest in Attica’s Riverside Cemetery. His wife, Maria E. Carter Brown, died on May 8, 1894 in Attica and lies beside him.

In 1987, John Cottrell, who was born and reared in Indiana and graduated from Attica High, began renovation of the Old Church through the John Cottrell Foundation. He then acquired the area adjoining the Old Church and restored the Norman S. Brown house, the William Brown house and a variety of other out buildings. In 1995 the Canal Society of Indiana visited this restored village.

Norman’s home was originally built in the early 1850s when he and his wife moved to Attica. It was located in a key area of the city because the water system originating from the Ravine Park springs came to this corner through hollow logs. Of Federal style, it originally was a rectangle with detached kitchen. At one time it had a smokehouse and barn. It was remodeled in the 1880s. When restored by Cottrell it was taken back to its original style.

William’s home is believed to have been built in the mid-1850s. Norman and Maria had it built as a wedding gift for William and his new wife. It originally sat two blocks away but was moved to its present location when a grocery was erected at its original site. It was restored as it was built.

Sources:

Ancestry.com: Public member trees:

Avery Brown, Laura McKee Brown Otis, Norman S. Brown, Maria E. Carter, William A. Brown, Laura Amelia Brown, Harley Brown

U.S. Federal Census: 1850, 1860, 1870, 1880

Beckwith, Hiram William. History of Fountain County, Indiana. Chicago, IL: H. H. Hill and N. Iddings, Publishers, 1881.

Find-A-Grave: #41412578 Norman S. Brown

Wabash and Erie & Whitewater Canals in Indiana and Their Connections to Indiana Railroads

By Brian Stirm

One of the most interesting developments that occurred due to the demise of the Midwestern canals and especially those in Indiana, where much of the canal right-of-way was sold off shortly after the canals ceased operation, was the proliferation of railroad rail beds being located on the former towpaths of said canals. Most canal buffs also have interest in other forms of transportation technology and I, like others, have been fascinated in the canal railroad connection in Indiana. There has been quite a lot written about this subject area so I thought it would be great to document some of it in one single source article.

Just to be clear for those who have not discovered this, most transportation corridors have been re-used many times over history. Many locales especially in Indiana have a number of transportation systems running in the same corridor. This started many years ago with the first native Americans following the animals for hunted food. The animals, needing water for subsistence as do all creatures, followed rivers and streams as natural pathways or maybe even as a barrier that made crossing from one side to another difficult. The animals also discovered that low lying areas were difficult to walk through because of the mud on their hooves so sought relatively dry trails not too distant from water to traverse. The native Americas followed them and after the discovery of the canoe traveled the waterway for a little faster method of getting from place to place. This also placed their settlements relatively close to those same waterways. Rivers and streams then became a major form of transportation with a slight problem. Due to the natural fall of the land that allowed rainfall to travel downhill to the sea, traveling up-stream on a river or stream was quite difficult against the natural water flow. When paddling up-stream the arm muscles became quite tired which slowed forward speed to a crawl. This of course spawned the development of other sources of power to move up-stream but we are getting way ahead of the canal era story for that.

The human quest has always been for increased speed in transportation to save time for other endeavors. Since going up stream was slow why not float a boat on level water making it easier to travel up stream with arm or animal power. Thus, the canal concept was born by using the existing travel corridor as it had been over time but by increasing the speed or at least equaling the speed going both ways. Canals developed a level waterway with the aid of lifting locks adjacent to the existing waterway for transportation and even used the water available from the rivers and streams to keep the waterway full. The animal towing power used an adjacent level pathway to walk on to pull the boats both upstream and downstream. This system existed in Indiana for several decades or so before the quest for speed and year round dependability placed it into the abandoned technology category.

Railroads were then the next transportation system starting first with the movement of people due to the weak crude nature of the steam locomotive. Freight transportation required much more power to pull and normally did not require a very fast speed of delivery. This suited the canals well so both transportation systems existed for a while together. With the advent of coal power and the super-heating of steam, railroads took over the freight transportation and soon the canals faced huge infrastructure repair costs with diminished freight and passenger revenues. The predictable end of canals came quickly at this point and the canal towpaths, both being level and well compacted from animal hooves, made great rail beds.

The transition from canals to rails was somewhat of a leap frog game between the two transportation systems. The early railroads in an area such as north central Indiana where the canal was still viable built new right of ways parallel to and in a competitive position to drive the canals out of business. Then when the canal had failed and the tow paths were available a second generation of railroads took over the tow paths and competed with the first railroad. This was especially true with the coming of electric railroads known as interurbans just after the turn of the century. The Wabash and Erie Canal to railroads transition is a great example of this. The Wabash and Erie was built between Lafayette, Indiana and Toledo, Ohio. It started in 1832 at Fort Wayne and was finished to Lafayette and Toledo by 1843. It was later extended to Evansville, Indiana by 1853 although this southern portion was not as viable as the Lafayette to Toledo section. The canal existed until 1874 but the Toledo, Wabash and Western Railroad, a merger of two shorter lines in 1856, followed the canal almost exactly from Toledo to Lafayette. This was the chief competitor for the canal’s business that it ultimately succeeded in taking.

As the canal failed and the tow path became available other railroads competing with the Toledo, Wabash and Western came into the picture as is witnessed by the information below:

This data came from an article published by the New Haven Area Heritage Association

PO Box 94 New Haven, Indiana 46774 entitled CANAL HISTORY – 1828-1881*

*This information was obtained through the courtesy of the Fort Wayne Historical Society. Also, parts were obtained through the New Haven Centennial booklet, dated 1966. This information was made possible by the New Haven Festival Committee, 1980.

A period of slow decline came in the 1870s as sections of the canal were abandoned. It had worn out and there was no money to fix it. Towns were now begun with the section between Newberry and Terra Haute and ended in 1882 with the draining of the section between Fort Wayne and New Haven to make way for the Nickel Plate Railroad tracks, which were laid in the old canal bed. For a time, the St. Joseph feeder canal remained in operation and the aqueduct across the St. Mary’s River carried water to the mills on the east bank of the St. Mary’s (just north of the Main Street Bridge) and to the cities mills near Clinton and Superior Streets. Eventually this service ended when the mills converted to steam power and the neglected aqueduct finally fell in 1905. This event marks the end of the period of existence of the Wabash and Erie Canal as a viable waterway.

Similar information was found in Wikipedia about railroads using or competing with the W & E canal through Indiana:

The right-of-way through Fort Wayne was purchased by the New York, Chicago and Lake Erie Railway (the Nickel Plate Road) which ran from Buffalo to Chicago. This allowed the railway to run straight through the heart of a major Midwestern city without razing a single home. The canal right-of-way was also directly adjacent to downtown, which made the new railway quite convenient for passengers and many businesses. The canal from Napoleon to Toledo was paved over to make U.S. Route 24.

Moreover, by 1872, the Toledo, Wabash and Western Railway connected Toledo, Fort Wayne, and Lafayette. The original canal, with its slow pace and maintenance issues, struggled to compete with many rail lines in operation in the 1870s.

In addition, along the rest of the Wabash and Erie Canal the Interurban, which competed directly with the TWW came into play as, portrayed in the book “Fort Wayne and Wabash Valley Trolleys, Bulletin 122 as published by the Central Electric Railfans’ Association in 1983. In this book, much of the canal towpath is described as being used by the various interurban rail companies. Initially, most interurban companies were local affairs with relatively little advance planning toward the integration of lines into any eventual semblance of order. For example, the Wabash River Traction Company (WRT) was the first successful interurban operation in the upper Wabash Valley. Construction was started on the Wabash-Peru line, in March 1901, on what proved to be little more than a rural trolley line. The streetcar lines in Wabash were extended southwest along Mill Creek to a point approximately midway between Wabash and Peru. This point known as Boyd Park became the powerhouse and car barn. A picnic grounds area was also purchased and developed. From Boyd Park, west to Peru, the Wabash River Traction acquired the right to use the abandoned Wabash and Erie Canal towpath. This pathway totaling 18 miles led all the way to Peru.

The Fort Wayne & Southwestern Traction Company, the “Southwestern” route, made an almost simultaneous start with the Wabash River Traction Company. The Southwestern was capitalized at $600,000 and called itself the “Canal Route” using the ideal but meandering canal banks of the Wabash & Erie Canal for its roadbed. The Southwestern gained control of the canal from Fort Wayne to Huntington and from Huntington to Wabash as well as options on the old canal beyond and to the west of Wabash. Ownership of the abandoned canal right-or-way had changed hands several times and had been proposed for a rail line by more than one of the earlier promoters. The Wabash Railroad, which had accelerated the canal’s demise, was never more than a few hundred yards away from the Fort Wayne to Lafayette portion of the canal. Construction on the Huntington-Fort Wayne line of the “Southwestern” started at several points between those cities during early 1901. Most of the trackage was along the canal right-of-way running from the Erie Railroad at Huntington to Taylor Street in Fort Wayne.

And relative to the White Water Canal in south east Indiana this article from abandonrails.com

Photo by Howard E. Espravnik, March 2010.

Note: Some of this information was drawn from the Whitewater Valley Railroad Museum.

By the early 1850s, railroads were eclipsing canal technology in the U.S. Railroads were not only cheaper to build and maintain, they were considerably more versatile than canals. Rail lines were not restricted to circuitous water-level routes or dependent on erratic rivers like their canal counterparts. And transportation by railroad was much faster than by canal, which was restricted to a walking pace. Indeed, the railroad seemed to offer everything canals could not. Unable to compete, most of the country’s canals eventually succumbed to the ever expanding railroad network.

By 1855, the struggling Whitewater Valley Canal Company was in the hands of a receiver and by the early 1860s the canal could no longer support reliable navigation. In 1865, the Whitewater Valley Railroad acquired the canal at auction and two years later it laid its tracks over the towpath of the Cincinnati & Whitewater Canal from Valley Junction, Ohio to Harrison, then over the towpath of the Whitewater Canal from West Harrison, Indiana to Hagerstown.

Though never a major trunk line, the Whitewater Valley Railroad served its customers well. It linked communities like Metamora and Brookville to a vast network of rail lines that, by 1869, spanned the continent from coast to coast.

The Whitewater Valley Railroad, however, soon found itself in financial trouble. In 1890, it leased itself to the Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago, and St. Louis Railroad–better known as the “Big Four.” In 1930, the Big Four was incorporated into its parent company, the New York Central. In 1933, the New York Central terminated passenger service on the Whitewater Valley line–a decision that reflected the ever increasing popularity of the private automobile. By 1932, one could drive on the new U.S. 52, which continues to parallel the old canal route from Metamora to Harrison.

In 1968, the merger of the New York Central and Pennsylvania Railroads brought the Whitewater Valley route under control of the Penn Central. Freight operations over the line between Connersville and Brookville came to an end in 1972. The non-profit Whitewater Valley Railroad then leased the line between Connersville and Brookville from Penn Central for excursion purposes.

In 1974, a section of track between Metamora and Brookville washed out. Having decided to not fix the damaged track, Penn Central abandoned five miles of track between the north end of Brookville and about two miles south of Metamora. In 1983, the Whitewater Valley Railroad Museum purchased the Connersville to Metamora track from Penn Central. Whitewater Valley Railroad Museum continues to operate passenger excursions to the end of the track south of Metamora.

Today, the Whitewater Canal Trail occupies much of the abandoned Penn Central roadbed (formerly canal towpath) from Metamora to the Twin Locks, and again at Yellow Bank Creek. The Indiana & Ohio Railroad continues to service Owens Corning at Brookville via the old canal route between Brookville and Valley Junction, Ohio.

Thanks to Howard E. Espravnik for contributing information about this route. Much of it came from Don Burden’s thesis The Whitewater Canal: A Historic Corridor Guide published by Ball State in 2006. Comments after Espravnik’s article was published noted that the Whitewater Valley Railroad is an operating Museum between Connersville IN and Metamora IN with stops in Laurel, IN and that the change to rail from canal was not as simple as this history portrays. The Ohio canal section (Cincinnati and Whitewater Canal) was railroaded in 1864 but the Indiana section took longer to get clear title to and the rails were not laid there until after 1866. In other words, it was more complicated than described. The Cincinnati & Whitewater Canal received rails first, followed by the WWC in 67 and 68.

Other comments were: In the 1980’s the Railway Exposition Corporation, a non-profit museum, proposed to operate trains between Brookville and Cedar Grove to the south. They had a Louisiana and Arkansas ten-wheeler, a Kansas City Southern Stuart Knott sleeper, and a L&N tavern Lounge car, as well as a Brookville Industrial switcher and a caboose or two. The line was to be named Cedar Gove, Brookville and Northern. Another proposed and stillborn line in Ohio, the Cincinnati, Morrow and Little Miami never materialized as a tourist line, and tracks were torn up, and part is a bicycle trail.

This line never came to pass. There had been a partial washout of a bridge near Cedar Grove. Had the line not washed out east of Metamora, perhaps they could connect with Whitewater Valley. The Whitewater valley did add about a mile to their run when they built a Grand Central Station in downtown Connersville. A depot has been moved south of Connersville, and Dearborn Tower has been moved there and is restored. The Railway Exposition Company museum eventually located in Kentucky.

In addition, in more about canals to railroads in southern and central Indiana, we have this article, which came from southernindianatrails.freehostia.com entitled Wabash and Erie Canal and reads:

The Railroad

The Lake Erie, Evansville, & Southwestern Railway Company was organized Apri1 23, 1871 for the purpose of constructing a railroad “to commence at Evansville, in the County of Vanderburgh, in the State of Indiana, and run from thence through the counties of Vanderburgh, Warrick, Pike, Dubois, Orange, Washington, Jackson, Jennings, Bartholomew, Decatur, Ripley, Franklin, and Union and terminate at the line dividing the States of Ohio and Indiana, at a point on said State Line at or near the town of College Corners.” This railroad was built from Evansville, a distance of 17.5 miles, to Boonville in Warrick County, Indiana, and opened for operation to that place on August 4, 1873. In Vanderburgh County and as far as Chandler in Warrick County this railroad was built on the towpath and on the right-of-way of the old abandoned Wabash-Erie Canal. The property owners, including Mary S. Stockwell, believed that the Canal property should have reverted to the original owners when the Canal was abandoned. The courts were petitioned for an injunction and abatement of the construction of the railroad, which by that time was being called the Airline Railroad. The suit was finally taken to the Indiana Supreme Court, where it was settled in favor of the railroad. The railroad was extended and reorganized and eventually became a part of the Southern Railway System. The tracks have remained in that location on the towpath of the Canal.

And from the Indiana Transportation Museum’s web site some history about a railroad built specifically to tie Indianapolis to the Wabash and Erie Canal at Peru:

History of the Nickel Plate Heritage Railroad

FRANCIS H. PARKER is professor and former department chair of urban planning at Ball State University. Author of Indiana Railroad Depots: A Threatened Heritage, he is currently on the Board of the Whitewater Valley Railroad, and owner of the former Muncie and Western Diesel Locomotive #8. A wealth of information can be found in his book Railroads of Indiana authored with Richard S. Simons.

The Peru & Indianapolis was incorporated January 19, 1846, to connect Indianapolis with the Wabash and Erie Canal at Peru. Construction began at Indianapolis in 1849 and service began over 21.42 miles of line to Noblesville on March 12, 1851. At the request of the Noblesville merchants, the railroad was built in 8th street to reduce the drayage cost for local freight. As the railroad built north it stimulated the location of new towns like Buena Vista, renamed Atlanta in 1881.

The Peru & Indianapolis was incorporated January 19, 1846, to connect Indianapolis with the Wabash and Erie Canal at Peru. Construction began at Indianapolis in 1849 and service began over 21.42 miles of line to Noblesville on March 12, 1851. At the request of the Noblesville merchants, the railroad was built in 8th street to reduce the drayage cost for local freight. As the railroad built north it stimulated the location of new towns like Buena Vista, renamed Atlanta in 1881.

The Peru & Indianapolis opened to Tipton in 1852, to Kokomo in 1853, and to Peru, 73 miles from Indianapolis, in early 1854. It was built originally with strap iron rails, and owned no equipment of its own. The daily mixed train was operated under a lease agreement by the Madison and Indianapolis Railroad. In 1856, the road replaced the strap-iron rails with 50 lb. iron T rails, and acquired three locomotives of its own, but the expense soon forced it into receivership.

In 1864 the P & I was reorganized as the Indianapolis, Peru & Chicago. In 1871 the IP & C took over the 88 mile Chicago, Cincinnati & Louisville, a recently consolidated chain of roads between Peru and Michigan City. The resulting 161-mile line between Indianapolis and Michigan City would be operated as a single operating division for the next 90 years, under a succession of owners.

Therefore, when you think about the railroads in Indiana be thankful that many would not exist had it not been for the Canals of Indiana.

Commission Approves Road Name Change

By Sam Liggett

A proposal to change the name of McDaniel Road to Erie Canal Road from Davis Drive to the 641 interchange in Terre Haute, Indiana, was approved by the Vigo County Area Planning Commission on Wednesday evening, March 2, 2017. Although this was all the same road, in the past Erie Canal Road changed to McDaniel Road at Springhill Drive. To avoid confusion, the commission has voted to call the entire road Erie Canal Road.

This name change is much better than having two names for the road and calls attention to the canal. However, the canal was the Wabash & Erie Canal not to be confused with New York’s Erie Canal. Wabash & Erie Canal Road would be a much better name for it.

Boating on the Ohio River

By Jeff Koehler

Traditionally, the Koehler family has never been known as “boat people.” The only boat my family had ever owned was a twelve-foot John boat with two oars. I always enjoyed spending time with my maternal grandfather, John B. Pell, on his cabin cruiser the Jonila, which he had fondly named after himself and my grandmother Hila. In 1967 Grandpa Pell, with two other boat mates, made a trip from Evansville, Indiana, to Ft. Myers, Florida. They traveled down the Ohio River to the Mississippi River and on to New Orleans. Once entering the Gulf of Mexico, they used the Intracoastal Waterway and eventually ended up in Ft. Myers Beach, Florida. They kept a colorful log of their trip.

Tales of Grandpa’s trip have always appealed to my more venturous side, so after reaching sixty plus, I decided it was time to knock one more thing off of my bucket list. Two years ago, my brother-in-law Mark and I stated talking about making a trip to the Gulf of Mexico via the Tennessee Tombigbee waterway. Using this route, boaters emerge into the Gulf of Mexico at Mobile, Alabama. I casually searched Craig’s List for an old boat that would be sufficiently sea worthy to make this trip. One such boat popped up just as we began talking about the trip, and it was just fifteen miles away from home. After looking the boat over, I purchased it, a 1973 Marinette that had been sitting in a machine shed for seven years. After a month of repairs and painting its bottom we transported the boat to a slip in Evansville, Indiana. The first summer required many more repairs and fine tuning the engines. Much time was spent on learning how to maneuver the boat. I also had to master the correct procedure for contacting the lock master and locking through locks. Also, of utmost importance, I learned to be vigilant of barge traffic and how to safely pass these barges on the river. Building enough confidence to make a long voyage of several hundred miles was not going to be an easy task.

The summer of 2015 ended with no long trip, and I brought the old boat home for another winter of updating. I installed a water heater and shower. I also rewired the AC electrical system. By the spring of 2016, we were anticipating an eventful year on the Ohio River, Mark and I decided that before we set out for the gulf, we should take a shorter trip of about a week to see how we handled traveling through the river system.

I took the boat back to Evansville in April of 2016 and settled into the slip at Inland Marina. The marina is located next to the World War II LST 325 on the south side of town. We had set a tentative date sometime at the end of July for our trip. Since I farm, I had to wait until I could get away, and we were finally able to set the date of departure on July 26, 2016.

Mark and I arrived the day before in anticipation of getting an early start on the morning of the 26th. We woke up at 65 A.M. to set out, but a very thick fog moved in and delayed our departure until 9:30 A.M. We had wanted to get started early to make our planned stop for the night a Golconda, Illinois, 115 river miles away. Trying to save gas, we ran the engines at a lower RPM and traveled at 9 knots per hour. We knew it was going to take all day to reach our first stop. Last summer, there were several heavy rains that kept the river elevated for long periods of time, which was the situation at the time of our trip. When the river is up, boaters have to be very vigilant in looking for debris floating in the river. One Propeller strike could make for a very unhappy day or two of repairs. We had GPS to help us along and calculate our speed.

As we made our way down stream, we met several tug boats pushing mostly coal or grain. The same large bulk products that the historic canals transported are still the ones being moved by barges today. On the first day of our journey, we passed numerous coal and grain loading facilities. Mt. Vernon, Indiana, has several large river terminals for various industries. Mt. Vernon has a large public access boat ramp, surrounded by a beautiful green lawn, and at the top of a hill, the courthouse dome is visible from the river. At 2 P.M. we arrived at the John T. Myers lock. This is the first lock we passed through on our journey. We were told by the lock master to tie up along the lock wall and wait on an up bound tug. The first locking through took an hour, but fortunately we experienced no problems. The process requires boaters to tie their boat to a floating pin against the lock wall. This is done to secure the boat from the swirling waters within the lock chamber. From this first lock experience and all the other locks we passed through, we learned at least one thing: Lots of debris congregates in the locks—logs, sticks, trash, and much more.

Later, it became very cloudy and rain was intermittent as we passed by the mouth of the Wabash River. At this point, we knew we were going to be very close to dark when we arrived at the marina at Golconda. The marina closed at 4:30 P.M., so we called ahead to make arrangements for a slip and a plug-in for electricity. Not wanting to anchor out for the evening, we sped the old boat up and pushed along at 15 knots per hour. During that first day, we saw very few recreational watercraft although we passed numerous barges going both upstream and downstream. We passed other river towns, some notable and others barely visible from the river.

Late in the afternoon, we cruised by Cave-In-Rock. The Canal Society visited this landmark several years ago. According to my grandfather’s journal, this is where he and his friends spent their first night. In 1967, there was a dock and motel close by the river. They had left Evansville in late November to make their journey. It was, of course, cold. By the time they reached Cave-In-Rock, ther were quite cold and ready to stop for the night. They secured a room and had to pay an extra dollar for the night to get a heated room. We pressed on as the sun would soon be setting in the western sky.

Finally, we reached the opening to the marina at Golconda, Illinois, at 7:45 P.M. We found our slip and parked the boat for the night. Golconda is a great little town with old store fronts and an active historical society. The Pope County seat is located there with a wonderful courthouse square. The courthouse is small, but very unique. There were two restaurants/bars on main street. We ate at the one named Diver Down, which I recommend to anyone. I plan to revisit this town when I can spend more time.

The next day we woke early to prepare for the next leg of our journey. After filling our tank with gas, we set out for a 50-mile trip to Green Turtle Bay Marina in Lake Barkley. It was a beautiful morning; we made good time and reached the Smithland Lock around noon. A boater can contact the lock master several ways—by radio (our first choice), by cell phone, or by pulling a long chain that is positioned at the end of the lock wall.

After locking through the Smithland Lock, the mouth of the Cumberland River is not too far downstream. We entered the Cumberland and then headed upstream for approximately 30 miles. I was very surprised by the narrowness of the channel. It didn’t seem any wider than the Wabash River, yet we encountered a vibrant amount of barge traffic the first few miles on this route. Along this river, we passed several of the largest rock quarries I have ever seen. Another problem, in addition to the barge traffic that we encountered, was floating debris, which necessitated a constant vigil to avoid a prop strike. We reached Lake Barkley Lock and Dam at 5 P.M. After several tries on the radio failed to make contact, we were able to reach the lock master by phone.

The Lake Barkley Dam, built by the TVA, is a hydroelectric dam. The lift is 57 feet, and the inside of the lock chamber is quite large. We encountered some additional unwelcome debris in this lock—around 100 very large, dead, smelly fish making our locking experience seem to take forever. Once we were up to lake level, we traveled only a sort distance to Green Turtle Bay Marina, a welcome sight. As we arrived, the western sky was blackening with ominous storm clouds and lots of lightning. We tied up for the night and weathered the storm in the boat. After the storm subsided, we headed out to eat.

The next morning we took the courtesy car, provided by the marina, to the local grocery store and restocked needed supplies. Then we departed Green Turtle Bay for the next day of adventure. We headed south and entered the channel between Lake Barkley and Kentucky Lake. Under a gray overcast sky, we entered Kentucky Lake and headed south with the goal of reaching Ken Lake Marina for our next stop.

We arrived at Ken Lake Marina around 2 P.M. to make our earliest stop on the trip. We met several great people and were fortunate to arrive on the night of their marina community cookout. Gratefully, we joined them and enjoyed a wonderful social evening. All of the other marinas we had visited had great restroom and shower facilities. Ken Lake Marina had good restrooms, but no showers. This made the shower addition on the boat very welcome. Upon departing Ken Lake Marina, we planed to turn around and head back to our home port of Evansville.

The next morning we gassed up and headed back north in Kentucky Lake. We had come to a conclusion, our boat loves gasoline. Even running at low RPMs, it was thirsty. From this point, we retraced our path and headed back to Green Turtle Bay for the night.

While docked at Green Turtle Bay, we met two other boats headed our way. We were happy to have some traveling mates. As we were departing Green Turtle Bay the next morning, we discovered we had an exhaust leak that needed immediate repair and had to abandon our new found travel partners to return to the marina for repairs. Fortunately, we located the needed parts to quickly make repairs and were soon on our way. We locked back though the Lake Barkley Lock and made great time downstream in the Cumberland River. After arriving back in Golconda Marina at 7:30 P.M., we headed to Diver Down for another great meal.

The next morning, we wanted to make an early start for the 115 mile trip to Evansville. However, we were again plagues by a heavy fog. The fog finally lifted enough, and we could make way for home port. We had not traveled ten miles when we started hearing strange noises from the engine compartment. After examining the problem I discovered the new exhaust hose had burned through again. This caused a big change of plans. While Mark piloted the boat, I patched up the exhaust with aluminum foil and duck tape for a temporary fix. I knew it wouldn’t last if the engine ran any amount of time, so we just had to shut down one engine and try to make it home at a slower pace. We knew this meant a night anchored out on the Ohio River, a new experience. Five knots per hour seemed like a terribly slow speed, but it was faster than the tug were traveling on the river. If there was any positive aspect to traveling with one engine, it was that we burned only half the amount of gas. As the scenery inched by and the sun began to set, we began looking for a place to anchor for the night. As it was nearly dark, we decided to pull up against the opposite river bank from Mt. Vernon, Indiana. We cast out our anchor, started the generator, and settled in for the night. The generator is not large enough to run the air conditioner, so we sweltered all night in the hot humid environment, which reminded me of the stories of traveling on a canal boat during the hot Indiana summer. I don’t think I slept much more than an hour for fear of drifting in front of a large tug boat.

As soon as it was light enough to travel, we started out on the last leg of our journey. The river was high and caused us to be on a constant lookout for logs headed our way. If there was a positive aspect to a high river, it was that it allowed us to cut around the back side of some islands and shorten our trip.

We were happy to round the bend of the river passing by downtown Evansville and to make Inland Marina around 12 noon. We fueled up the boat and took a shower in the marina. We had survived our eight-day ordeal and hope to make the longer trip to the Gulf of Mexico someday in the future.

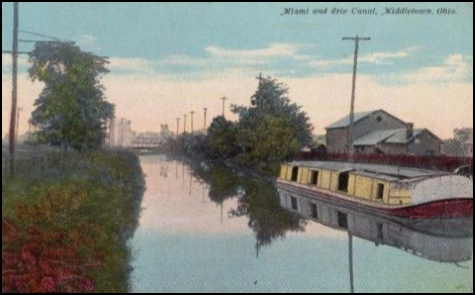

Picture Found of Boat on the Miami & Erie Canal

News From Delphi

Remembrance Walk

On April 30, 2017 at 3 p.m. a Community Trail Walk was held on the Monon High Bridge Trail in remembrance of Liberty German and Abigail Williams, two young girls who attacked while walking the trail. Todd Ladd, the pastor of United Methodist Church in Delphi, wanted the community to come together in the celebration of the girls’ lives, the celebration of the trails, and the celebration that steps can be taken towards wholeness. He, along with others from Camp Tecumseh and Delphi Historic Trails, led the walk and were interviewed at the church following the event.

Spring flowers like the shooting stars pictured here were seen along the trail.

Bison Award

Frances French, Secretary of the Carroll County Wabash & Erie Canal board, received the Bison Award for Volunteerism from Bison Financial. Also attending the ceremony held in Lafayette, Indiana, were five others from CCW&EC, who have received the award in the past seven years. In addition to the carved Bison given to Frances, the organization received a check for $750.

New Exhibit

A new railroad display showing an old fashioned steam engine running circles around a slower canal boat is being completed by volunteers. Grants for the exhibit were received from the Canal Society of Indiana and the Carroll County Community Foundation.

Final Touches

Final Touches

Mac Carlisle used his talents to work on details involving the water model and its miniature lock gates in the Canal Interpretive Museum in Delphi, Indiana. It was finished just in time for the end of the year school tours when hundreds of children visit Canal Park.

A Special Donation

A Special Donation

Melissa Rodkey Shalicky of Fort Wayne, formerly from Carroll County, offered to donate a beautiful old Lutheran Church pump organ to place in the restored Lutheran Church in Canal Park after attending a presentation in Fort Wayne by Dan McCain about Delphi’s volunteers. The organ’s bellows are in need of some repair.

“The Delphi” Somewhat Copied

“The Delphi” Somewhat Copied

A new craft very similar to “The Delphi” has arrived in Fort Wayne, Indiana. It will mimic a canal boat and operate on the St. Joe River near downtown Fort Wayne. Here Dan Wire shows off the floor space of the new boat.

Meanwhile “The Delphi” was readied for the summer season on the Wabash & Erie Canal in Delphi’s Canal Park. Heading up her crew is Captain Steve Gray and first mates John Polles and Bill Lapcheska. Other volunteers are being sought to man her.

Carroll County W & E Canal Annual Meeting

Carroll County W & E Canal Annual Meeting

On Tuesday April 18, 2017 Kevin Stonerock entertained those attending the annual meeting as a Steamboat Captain, which involved music, acting and stories.

Canal Boat Rides

Canal Boat Rides

Take yourself back in time to an era highlighted by canoes to steamships, from horses to canal boats — where would modern society be without appreciating yesterday’s modes of transportation. Celebrate the early manmade waterways and the 1850’s way of life at Canal Park any weekend from May 13th through Labor Day. Narrated 40 minute cruises are offered to the public on Saturdays and Sundays at 1:30, 2:30 and 3:30 p.m.

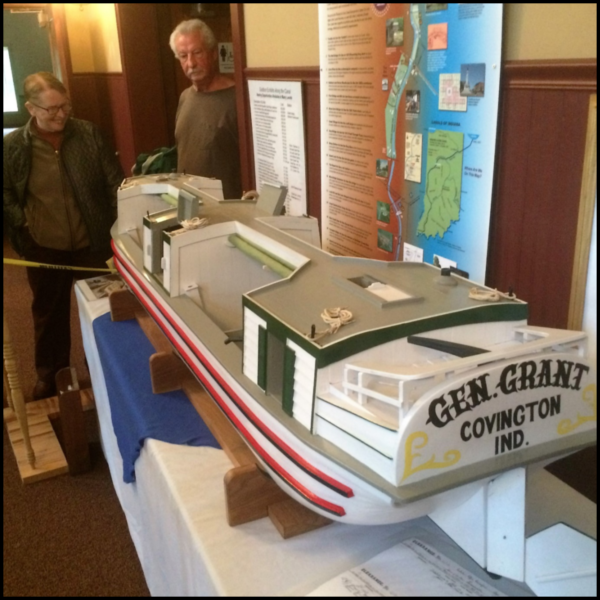

Also of special interest is the 1/8th scale model of a canal boat on display every afternoon in the Wabash and Erie Canal Center’s Grand Lobby now through mid-summer. Known as a Line Boat, this type of freight-carrying vessel frequented canals like the manmade Wabash & Erie Canal, delivering goods to the many towns along the 468-mile waterway from Toledo to Evansville. This model, named the GENERAL GRANT was built by Terry Bodine in his Covington, Indiana, workshop with the help of a friend Finny Filchak from Clinton, Indiana. The original 1850s full size boat was licensed in Covington.

Also of special interest is the 1/8th scale model of a canal boat on display every afternoon in the Wabash and Erie Canal Center’s Grand Lobby now through mid-summer. Known as a Line Boat, this type of freight-carrying vessel frequented canals like the manmade Wabash & Erie Canal, delivering goods to the many towns along the 468-mile waterway from Toledo to Evansville. This model, named the GENERAL GRANT was built by Terry Bodine in his Covington, Indiana, workshop with the help of a friend Finny Filchak from Clinton, Indiana. The original 1850s full size boat was licensed in Covington.

The Canal Center and its museum are open daily 1:00 to 4:00 p.m. Come and inspect this detailed, colorful, accurately scaled model.