INDEX

Schmidt’s Symposium Presentation

Frank Bash Interviews Citizens Who Remember The Wabash And Erie Canal

The Hagerstown Extension Of The Whitewater Canal

WHY TERRE HAUTE?

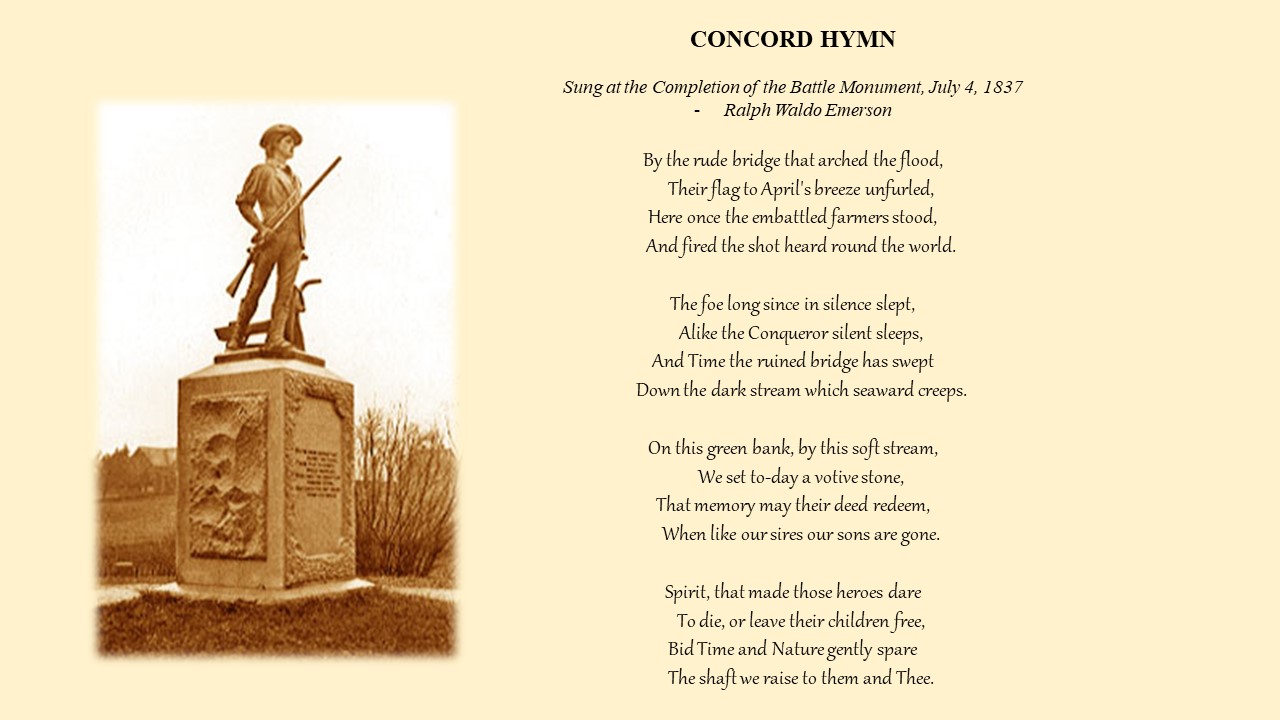

ROBERT SCHMIDT

Indiana’s canal era began with a Federal Land Grant in 1824. The state rejected this grant of a 90 foot right-of-way between the Maumee River in Fort Wayne and the Forks of the Wabash at Huntington. During the final days of Congress in March 1827, a bill was passed to provide Indiana with a more generous land grant. The proceeds from land sales were to be used to construct a canal from Defiance, Ohio to the mouth of the Tippecanoe River near Lafayette, Indiana. Indiana accepted this grant and began construction on February 22, 1832 in accordance with the terms of the grant. Although this initial construction was centered around Fort Wayne and northern Indiana, there was no headquarters as such. The state was in charge and its headquarters was Indianapolis.

Later in 1836 the works of the Mammoth Improvements Project were still based out of Indianapolis. When the state ran into financial difficulties in 1839 work was stopped on two of the canal projects, the Central and the White Water canals. The Wabash & Erie mostly funded by the land grant struggled but managed to reach Lafayette by 1840. Indiana received an additional land grant in 1841 to extend the Wabash & Erie Canal to Terre Haute, but by 1847 this project was still stalled and terminated at Lodi in Parke County.

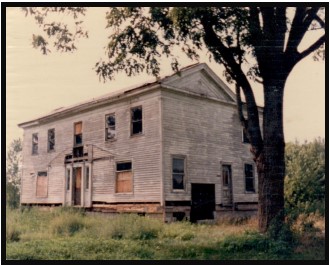

Connersville, Indiana

Photo by Bob Schmidt

Citizens in the Whitewater valley wanted to complete their canal from Brookville to Cambridge City. They formed a separate corporation and the state turned over its completed works. This new company was the White Water Valley Canal Company and was headquartered in Connersville. The primary reason that Connersville was selected was that it was the central location of the canal construction that was going to occur from Brookville to Cambridge City. A beautiful headquarters building was completed by this private company and the structure still remains today. CSI members will recall several of our tours viewed this building.

Charles Butler, a New York lawyer, was hired by the Indiana Legislature to resolve Indiana’s debt problem. After much negotiation his agreement was titled “The Butler Bill.” Terms of the agreement provided that the Wabash & Erie Canal would be built to Evansville in exchange for the properties of the canal already completed to Lodi. The state of Indiana would turn over all completed structures on the Wabash & Erie Canal to a Trust and Wabash & Erie Canal headquarters would be established at Terre Haute.

While Indiana was working with Charles Butler to resolving the financial problems of the canal, the Federal Government on March 3, 1845 passed another land grant for Indiana. This grant again provided land to sell for funds to extend the Wabash & Erie to Evansville. Terre Haute businessmen, led by Thomas Blake called for a special canal meeting to be held at Terre Haute on May 22, 1845. Each of the counties along the proposed route selected delegates to attend. While Vanderburgh County (Evansville) supported a Terre Haute location, other southern Indiana counties proposed that this meeting be held in Washington, Pike County. The Evansville Journal of May 28, 1845 reviewed several of these county meetings to appoint delegates. After the differences on location were resolved, the meeting was held on May 22th in Terre Haute.

Why Terre Haute? Not only had a precedent been set by holding this meeting at Terre Haute, but it was the central location of future construction. Terre Haute also had the business and political support to make it the headquarters for this extension. The other counties south of Lodi may have had a good location but were too small in size and didn’t have the political clout of Terre Haute. Charles Butler urged Col. Thomas Holdsworth Blake to return to Terre Haute from his job in Washington City (DC), where he was US Land Commissioner appointed by President Tyler. Blake was a key promoter of the canal extension as earlier he had been for the National Road through the city.

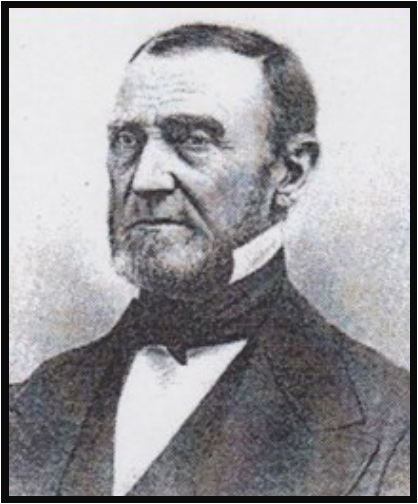

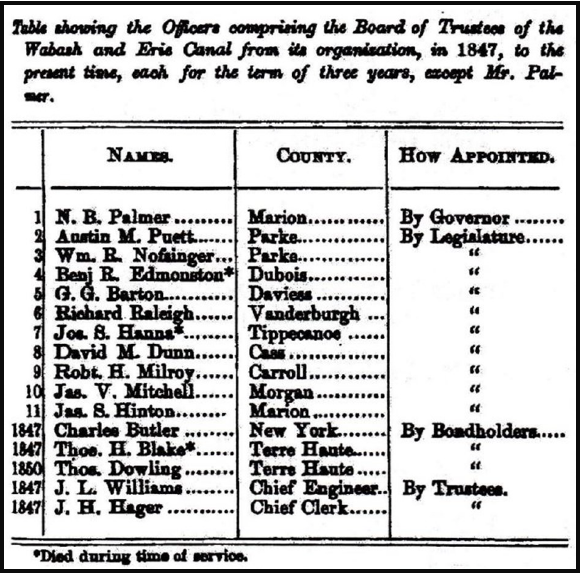

On July 31, 1847 Indiana’s Governor Whitcomb turned over all canal property to the Trust, which established Terre Haute as the new headquarters for the Wabash & Erie Canal. To administer the business, two Board Members were selected by the Trust – Charles Butler and Thomas Blake. A third board member was selected by the Governor or Legislature – Nathan Palmer. After a couple of months Palmer resigned and Parke County Legislator Austin Puett was selected. After Thomas Blake died in 1849, he was replaced by Terre Haute newspaper, businessman Thomas Dowling. Jacob Hager, who was serving as Secretary to the Indiana Legislature, was selected to be the financial clerk for the canal and moved to Terre Haute. Jesse Lynch Williams was appointed the Chief Engineer. Williams’ son-in-law, William J. Ball, moved to Terre Haute and performed the engineering for the canal extension to Evansville.

in Terre Haute

At the time the Trust was created the responsibility for the 88 miles of the Wabash & Erie Canal in Ohio were transferred to that state. Subsequently in 1849 the portion of the canal from Junction, Ohio to Toledo, Ohio was renamed the Miami & Erie Canal.

Photo by Bob Schmidt 1992

After canal headquarters were established in Terre Haute, Bankers Magazine of 1851 reported an increase of tolls for year ending 1st November, 1850 and the same period of 1849. It shows an “Increase of $22,511.92 less $2,228.36 received at the new office opened at Terre Haute during the summer.” The canal had reached Terre Haute by 1849.

We don’t know where the first headquarters under Thomas Blake were located in Terre Haute. However, following his death from cholera in 1849, he was succeeded as Resident Trustee of the Wabash & Erie Canal by Thomas Dowling. Dowling constructed a residential dwelling at 629 Ohio Street, on the south side of the street, to serve as canal headquarters. The two-story facility was completed on December 16, 1853.

On December 15, 1864 Dowling moved the canal headquarters to the “North Room” in Dowling Hall, the first structure in Terre Haute designed for entertainment. It boasted Indiana’s largest stage. It was located on North Sixth Street, south of Cherry Street. The earlier Ohio Street residence was sold to George W. Bement.

For three decades the Wabash and Erie Canal headquarters were in Terre Haute with Dowling in charge. He was confronted by canal opponents such as the Clay County militia, natural disasters such as floods and the negligence of employees, but he was very devoted to the canal sometimes paying expenses himself. He was the chief administrator when the canal reached the Ohio River at Evansville in July 1853. However, the canal fell upon bad times and had to be sold. Dowling conducted the auction of all canal lands in February 1876 at the Vigo County Courthouse in Terre Haute. He died that same year at age 70 on December 5, 1876 after a two-week illness.

Prior to 1877 the land records of Indiana were scattered with a few in the land department in Indianapolis, some in the office of the Secretary of State and the Wabash and Erie Canal land records were in the office of the Receiver of the canal at Terre Haute. The canal receiver was requested to turn in his records to the land office but persistently refused. The Secretary of State turned his in. Then in January 1883 the state Auditor asked the Honorable Judge Gresham for an order directing and requiring the Receiver of the canal to surrender these records and papers to the State of Indiana. The papers were removed from Terre Haute and placed in the land department in Indianapolis.

Photos by Bob Schmidt

Woodlawn Cemetery.

Photos by Bob Schmidt

To learn more about these Terre Haute canal personalities see their biographies on the CSI website — indcanal.org

SCHMIDT’S SYMPOSIUM PRESENTATION

ROBERT SCHMIDT, CSI PRESIDENT

Part 2

In the May issue of “The Tumble,” I discussed how the construction of the Erie Canal was so essential to the economic development of the Midwest. There were many events along the way with territory changing hands between countries and changes in the modes of transportation that could have resulted in a completely different outcome. Without the Erie Canal, the Midwest would have developed stronger economic ties with the South via the Mississippi route to New Orleans. In fact, I suggested that the Civil War may have had a completely different turn if the Midwest aligned itself with the Confederacy. Perhaps the Midwest would have even become a third country as the nation disintegrated.

In this review of my March 2023 Symposium presentation, I want to discuss the development of canal building in Indiana & Ohio. Here there were also many challenges that impacted the final orientation of these states to the eastern United States.

As early as 1784, George Washington recognized the significance of the short portage between the Maumee and the Wabash rivers. George himself never viewed any portion of the three rivers area. Fort Wayne’s Indian agent from 1812-1820, Benjamin Stickney, wrote a letter to Dewitt Clinton in 1817 pointing out how a canal at the Maumee/Wabash portage would fit nicely into Clinton’s planned Erie Canal project then under construction.

Even before Governor Clinton came to Ohio for the groundbreaking in 1825, Indiana was already thinking about a short canal at the portage. William Hendricks, while Indiana’s Governor in 1823, suggested to the Indiana Legislature that a canal should be built at the portage. He later became a U.S. Senator and was there when Indiana received the March 2, 1827 federal land grant to build the Wabash & Erie Canal.

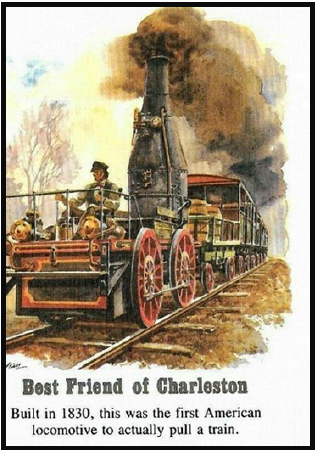

Before the land grant even was considered there were other delays. The land where the proposed canal was to be built had to be gained from native tribes. The Treaty of Paradise Spring in Oct 1826 at Wabash, Indiana acquired the right-of-way for the canal. Governor Ray, who helped in treaty negotiations, really favored railroads vs the enthusiasm for canals. Railroads were just in their infancy in 1830, as the illustration reveals. The engine was a primitive steam boiler placed on a platform on rails. In June 1831, the boiler on that train exploded and the engine was destroyed. As always, new technology takes time to perfect and work out the bugs. Economically Indiana could not wait for this steam powered engine to develop over the next 20 years. At that time the steamboat traffic on the Ohio/Mississippi was the main transportation connection for Hoosiers to the outside world.

Even passing the 1827 land grant was no small feat. The Whigs were in power and favored roads and canals, but Democrats generally opposed using federal support for internal improvements. The canal bill passed by just a few votes in the final days of John Quincy Adam’s administration. In 1828, the next legislative session, Andrew Jackson supporters took over. There would have been no Wabash & Erie Canal had it not just passed in the Spring of 1827. Remember that President Jackson vetoed a similar project in Kentucky, the proposed Maysville Road in 1830.

The terms of the 1827 Act provided for alternate sections of land be granted to the State of Indiana for 5 miles along either side of the selected canal route. The route was to be from the mouth of the Auglaize River in Ohio (Defiance) to the mouth of the Tippecanoe River just east of Lafayette, Indiana. Construction had to begin in 5 years and completed in 20. The canal was to be toll free for all federal use. Indiana accepted this grant on January 5. 1828.

This was a generous federal grant of 828 square miles that could be subsequently sold to raise funds for a canal. Two years went by as the route had to be surveyed and the land classified into 3 categories based on a standard for usability. Land offices were established in Logansport in 1830 and Fort Wayne 1832. The terms for land sales were most generous. One fourth down in currency and the remainder paid over 17 years at 6% interest. Most sales went to land speculators not new landowners.

Three Canal Commissioners to administer the canal for Indiana were selected in January 1828. They were Samuel Hanna – Fort Wayne, David Burr – Jackson County, and Robert John – Franklin County. Hanna, a real canal enthusiast, soon traveled East to obtain surveying equipment and worked on a survey for the St. Joseph feeder canal. David Burr was the postmaster in Salem and later moved to Wabash, Indiana. There in 1834, he helped Hugh Hanna, Sam’s brother, lay out that town. Burr later became instrumental in quelling the riot of the Irish near Lagro in July 1835. Robert John was mostly interested in obtaining a canal for the Whitewater valley. He resigned in just a few months and was replaced by Jordan Vigus of Logansport in May of 1829.

In January of 1830, a new 4 man reorganized board was created with 3 year terms. Jordan Vigus and David Burr were reappointed with Samuel Lewis replacing Sam Hanna of Fort Wayne. James Johnson of Lafayette was added as the fourth member. Samuel Lewis, who earlier came from Brookville had married the daughter of David Wallace, the future Governor of Indiana. Lewis was appointed sub Indian Agent in Fort Wayne and was also in charge of canal land sales.

Jordan Vigus was elected the first mayor of Logansport in 1829. He was the only Canal Commissioner at Fort Wayne for the canal groundbreaking on February 22, 1832. The date was selected as the 100th anniversary of the birth of George Washington. This Board of Canal Commissioners needed to find an engineer to finalize the work at the summit level. With some difficulty, they were finally able to hire the services of Joseph Ridgeway Jr., who was working near Columbus, at that summit level. He arrived in Fort Wayne in August 1830, completed his work in a few months and reported back to the Indiana legislature by December of that year. He wished to return to Ohio so it was necessary to find a replacement to implement his work.

The major engineers in Ohio were unable or unwilling to come to Indiana to start a brand new canal. They did recommend one of their own junior associates, Jesse Lynch Williams, who at age 25 was also working at the Licking summit near Columbus.

He and his wife Susan Creighton agreed to come to Fort Wayne in 1832 to tackle the canal project. Williams was immediately successful and was greatly respected for his leadership. The Legislature hired him in 1836 to be in charge of all internal improvements in the state. Years later, after his canal work was over, he was appointed by President Lincoln to the Board of Directors of the Union Pacific Railroad.

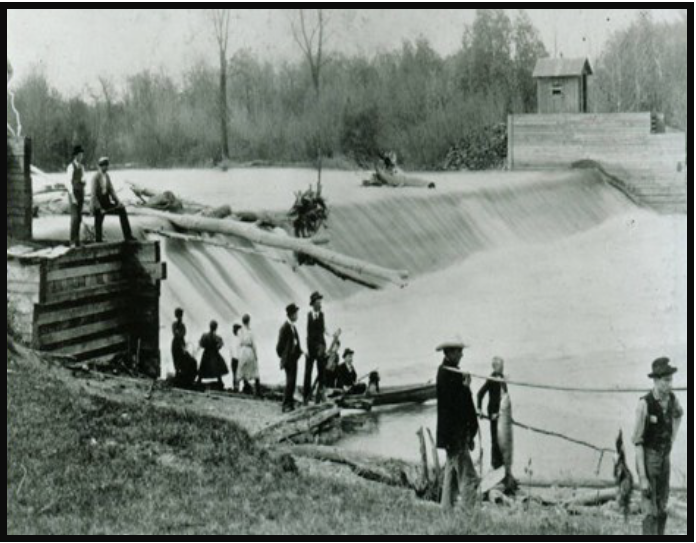

Valerius Armitage came from his work on canals in Pennsylvania to Fort Wayne and became a major contractor for the St Joseph Feeder Dam.

This key dam structure provided water for a 6½ mile feeder and 25 miles of water west to the Huntington Forks and eventually another 47 miles east to Defiance, Ohio. It had to be built so it could not fail. Armitage later moved to Logansport and then Delphi, Indiana for contract work there. He died unexpectedly at age 46. His daughter, Mary Jane, married future Union General Robert Milroy, who was the 1828 founder of Carroll county.

The primary reason for building the Wabash & Erie Canal was to provide a connection to Lake Erie and then by steamer feed into the Erie Canal at Buffalo, New York. Logic says Indiana would first build from the summit at Fort Wayne to the East toward Ohio. As you will see there was a major problem between Ohio and Michigan as to who really occupied the Toledo area. The W & E began at the feeder dam and proceeded along the 6½ mile feeder to near Lindenwood Cemetery in Fort Wayne. At the junction with the main canal, a basin was built toward the St Mary’s River and terminated at the St Mary’s aqueduct built across the St Mary’s river. The canal proceeded through Fort Wayne where two more basins were located and then on to the summit lock (Taylor’s) east of town.

To the west the canal proceeded 20 miles to the first lock (Burk’s) at the east end of Huntington. The canal to Huntington was opened officially on July 4th 1835 when Asa Fairfield piloted the first boat to town. Fairfield was a 37 year old sea captain who came to Fort Wayne bringing $30,000 in a satchel. He became an officer in the Fort Wayne branch of the Indiana State Bank.

Canal building in northern Indiana was proceeding well. The entire state now wanted internal improvements for their local areas. The Legislature responded with the Mammoth Internal Improvement Bill of 1836. Canals, railroads, roads and waterway improvements were all covered in this grand plan, one of the best of any state. Construction began everywhere without considering any funding problems. Indiana authorized $10 million in loans at 5% for 25 years.

The mid 1830s were a period of rapid economic expansion but also a period of rising inflation. Andrew Jackson hated the National Bank and refused to re-charter it in 1832. He removed federal funds from the National Bank to pet state banks, which resulted in these banks making speculative loans and inflating the currency. Federal Land being purchased was mostly with inflated state currency. In August 1836, Jackson issued his famous Specie Circular. This required that federal land sales be made in hard currency, gold or silver. Banks that had overextended credit failed and the country went into a depression. This was the basic cause of the failure of Indiana’s 1836 Mammoth Improvement projects.

Work on the Wabash & Erie still proceeded slowly to the west in the next few years reaching Lafayette, Indiana by 1840 and Lodi in Parke county by 1847. Funds were still available from land sales and the use of state promissory notes – Blue Dog $5 and Blue Pup $1 paper.

The Michigan / Ohio Dispute

Although Ohio had accepted the portion of the Indiana’s Land grant of 1827, she delayed building any of this canal in Northwest Ohio because of a territory dispute with Michigan.

When the Northwest Territory was created by Congress in 1787, five states were to be created. A line from the bottom of Lake Michigan was to run due east and intersect with Lake Erie, slightly above the terminus of the Maumee River. he Ohio Enabling Act of 1802 provided for that same terminology. Unfortunately the early map used in the legislation by Congress was in error. That map placed Lake Michigan further north in latitude that it was actually located. Using the precise terminology of the enabling act, the Michigan border was now further south and would cut Ohio off from the Maumee Bay at Toledo. The Buckeyes would have none of this, as they assumed the Maumee River to Lake Erie belonged to them. Ohio had already lost the “Gore” strip in the Whitewater valley, which was transferred to Indiana Territory back in 1802. The Michigan “Wolverines” were now trying to take some more Ohio land.

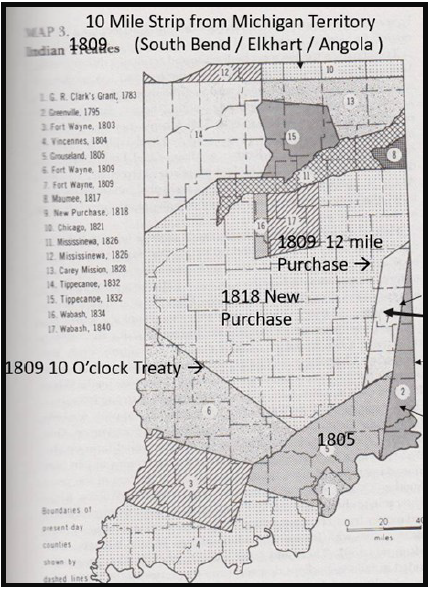

Ohio’s prior Governor, Edward Tiffin, who was now the Surveyor General of the United States, called for a new survey. William Harris was charged with taking a fresh look which placed the Maumee Bay into Ohio by starting at the base of Lake Michigan but moving at a angle intersecting Lake Erie at the original point intended. See the (upper line) on the attached map. Michigan Territory Governor, Louis Cass, objected and ordered a second survey by John Fulton. This survey (lower line), followed the literal terms of the original legislation, favoring Michigan and placing the Maumee Bay in Michigan Territory. The area in dispute amounted to about 468 square miles and was called the Toledo Strip. From the next illustration note that Indiana had earlier received a 10 mile border adjustment into Michigan Territory to give Indiana a port access to Lake Michigan.

Governor Lucas sent 600 Ohio Militia to the border and the new young Governor of Michigan Territory, Stephen Mason, sent about 1000 of his militia to “his” border. President Andrew Jackson tried to resolve the tension before violence erupted. Ohio was a state and Michigan was just a territory at the time. With federal

elections in play, President Jackson sided with Ohio. The Harris line was accepted as the Ohio/Michigan border, but, in exchange, Michigan Territory gained the “western” portion of the Upper Peninsula that was then Wisconsin Territory.

Even with the Ohio border issue resolved there were still problems at the mouth of the Maumee. The town of Maumee on the north side of the river was established in 1817 and Perrysburg in 1816, 2½ miles downriver on the south side of the Maumee. Both of these towns wanted the proposed canal to terminate at the Maumee River in a series of 6 stone locks. Seven miles further downriver were the towns of Port Lawrence 1817 and Vistula 1832. They wanted the canal to terminate at Swan Creek and then follow the creek for 1 mile to the Maumee. To strengthen their case, these two small villages combined to become Toledo in 1833 and then asserted that they had a deeper port location for lake steamers. Now a third contender for the canal terminus was Manhattan located 4 more miles downriver, right at the edge of Lake Erie. Established by some New York investors in 1835, Manhattan had some challenges. Although closest to Lake Erie, the main channel of the Maumee was located on the south side of the river. Another town, Lucas City, was suggested there but the canal was still going to be on the north side of the Maumee. The Ohio Canal Commissioners could not agree with this political situation and so terminated the Wabash & Erie at 3 separate locations – Maumee, Toledo & Manhattan. Canal construction began southwest of Toledo in 1837. Over the years only the Swan Creek terminus was active. The Manhattan line was abandoned in 1864 and the Maumee Sidecut was found to be less useful since the Maumee was too shallow for the larger steamers to come upriver.

By 1837 with Ohio canal construction near Toledo underway, Jesse Williams called upon Lazarus Wilson to engineer the W & E canal from the Fort Wayne summit to the Indiana state line. Wilson had an interesting background. He was in the 39th Maryland Infantry that fought near Baltimore at North Point Woods against the British in September 1814.

Later he was schooled in engineering and was called by Johnathan Knight to work on the National Road in Indiana. Wilson engineered the Washington Street Bridge on the National Road in Indianapolis. He moved to Fort Wayne and helped with the canal engineering there with Jesse Williams. In 1836 Williams sent him to Logansport for engineering work. Then in 1837 he was back in Fort Wayne to develop the 20-mile canal route to the state line. Check out his very interesting biography on this website.

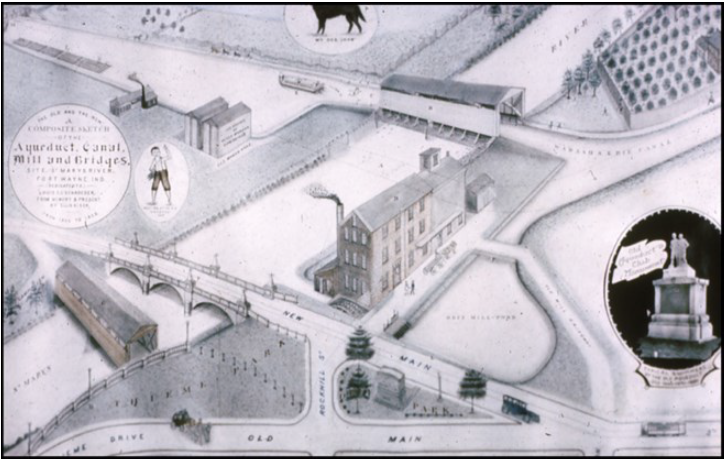

One of the uses of the canal was for waterpower. At the St Mary’s aqueduct site in 1842 Samuel Edsall and William Rockhill established a sawmill. Later Edsall established a grist mill called The Empire Mill. In 1856 he sold the mill to John Orff and the mill became the Orff Mill. Edsall was the Grand Marshall at the 1843 Grand Opening celebration in Fort Wayne on the nearby Thomas Swinney farm. Later in 1858 he was Treasurer of Allen County. His photo and the layout of the mill and aqueduct are shown on the attached photos.

I concluded the Symposium with a listing of canal era Governors and the Trustees of the Wabash & Erie Canal

Canal Era Governors:

James B. Ray

Noah Noble

David Wallace

Samuel Bigger

James Whitcomb

1825-1831

1831-1837

1837 – 1840

1840 – 1843

1843 – 1848

1828 Grant Accepted

1836 Mammoth Bill

1839 Financial Crisis

1843 Celebration FTW

1847 W&E to Trust

Canal Administrators 1847 – 1874

See complete biographies on our CSI website

My Final Conclusive Thoughts

The Wabash & Erie Canal was not the Erie Canal

Miles – Longest in US and 2nd in the World – Grand Canal of China

| Manhattan to Junction | 70 |

| Junction to Indiana State line (W&E) | 18 |

| Total in Ohio | 88 |

| Indiana Mileage to Evansville / Lamasco | 380 |

| Total W&E Mileage | 468 |

Erie Canal 363 miles

What if the Erie & Other Midwest Canals were not built?

Critical Period: Oct 1825 – Feb 1861 – 35 Yr

Did the Erie Canal Save the Union?

SHIP/BARGE CANAL PROPOSALS

CAROLYN SCHMIDT

Indiana’s canal era, which is normally thought to be from 1832-1876, actually wasn’t over in the minds of many Hoosiers and other Americans, who thought that canals were still the most economical way to transport large quantities of products. Some groups pursued building larger ship/barge canals.

1880

In 1880 the states of Ohio and Indiana partitioned the U.S. Congress to consider a ship/barge canal

connecting the Atlantic Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico via Lake Erie, and Wabash, Ohio, and Mississippi rivers. The canal was to be built the size of New York’s enlarged Erie Canal. It would be 70 feet wide at the water’s surface, 52½ feet wide at the bottom, and 7 feet deep. The locks would be double, 110 feet long, 18 feet wide, and 7 feet deep. All the locks and other structures would be of masonry and the bridges of iron. It could float a barge with a carrying capacity of 80,000 bushels of grain, equal to twenty railcar loads. It could be powered by either small steam launches or mules.

Congress was agreeable to this request and contemplated appropriating fifteen thousand dollars to pay the expenses of a survey and report. However, this amount was omitted before the final passage of a bill on June 14, 1880, and the expense of the survey was taken out of the general appropriations.

The following three routes were surveyed for the proposed canal:

- Major Wilson surveyed the first route from Lake Erie, at Toledo, Ohio, down the bed of the old Wabash and Erie Canal through Fort Wayne, Indiana to a point at or near Lafayette, Indiana on the Wabash River. The distance from Toledo to the mouth of the Wabash near Evansville is nearly 500 miles. The canal from Toledo to Lafayette was estimated to cost about $24,236,000 and it would require several million dollars more to put the Wabash River in a navigable condition from Lafayette to the Ohio River.

- The second route surveyed was from Lake Erie, at Toledo, Ohio, down the bed of the old Wabash and Erie Canal to near Defiance, Ohio at Junction City, and then by way of the Miami and Erie Canal to the Ohio River at Cincinnati, Ohio. The distance between Toledo and the Ohio River at Cincinnati being about 240 miles, a shorter route, but a more expensive one, being about $28,000,000.

- A third route surveyed ran from Lake Erie at Cleveland, Ohio, down the Ohio and Erie Canal to Zanesville, Ohio, then down the Muskingum River to the Ohio River.

The first two routes were found feasible after a survey in 1881 by Major John M. Wilson, U.S.A. The third route was abandoned because the Ohio River at the point where the Muskingum River entered it at Marietta, Ohio, was found too low for commercial purposes.

1881

In 1881 there was another ship canal that had been proposed, the Hennepin canal, from Chicago to the navigable water of the Illinois River. In 1892 construction began on this 75 mile long canal, which was eventually completed in 1907. It was soon abandoned due to railroad competition.

1887

An article in the Fort Wayne Gazette of October 7, 1887 reported, “The canal means for Fort Wayne a far greater boom than any railroad could give her. It would bring to our doors the manufactured goods of the north, with salt, lumber and other natural products, wool, grain, horses, coal, wood and thousands of bulky articles which are now shipped by rail at a great expense. It would mean direct water connection with all parts of the great lakes and all the towns and cities on the great rivers. It would mean the creation of a port of entry at Fort Wayne and the establishment of a custom house here. The boating season is eight months in length. The original survey includes tow paths for horses and mules, but the nature of the traffic would require faster locomotion and steam launches, with speed of five to seven miles an hour could be used.”

1888

The Fort Wayne Journal of January 25, 1888 said, “it (the canal) may become a channel of commerce, floating the grains of the north to the southern seaboard, or the cotton, lumber and other raw materials from the south to the northern factories and markets…With natural gas and a big ship canal, Fort Wayne would soon be the Chicago of Indiana.”

1894

After nothing was ever built on the original Indiana and Ohio proposals, another plan was put forth. The Fort Wayne Morning Journal of March 4, 1894 ran the following article written by I.L. Campbell in Crawfordsville, Indiana.

“A Ship Canal. Fort Wayne’s Great Opportunity. A Route Projected From Toledo to Chicago. The Wabash and Erie Canal, the Tippecanoe and Kankakee Rivers Provide a Waterway—The Routes Talked of —Mr. I. L. Campbell’s Strong Letter.

“A stupendous canal project, which, if successful, will entirely revolutionize the traffic of the great lakes, is said to be in contemplation by a number of capitalists in Chicago, New York, Boston and London. The proposed canal is designed to facilitate the passage of vessels from Chicago, Milwaukee and other northwestern points to the east, and to render entirely unnecessary the present long route through the straits of Mackinaw, Lake Huron, St. Clair River and like, and thence down the Detroit River to Lake Eire. The plan now under serious contemplation is to construct a canal directly across the state of Michigan from the eastern shore of Lake Michigan to either Detroit or Toledo, O. Should either of these plans prove feasible it will result in one of the most gigantic enterprises of the century. A number of capitalists from Chicago, New York and Boston are said to stand ready to back the project to the extent of $50,000,000, and it is also said the English capitalists who are interested in the Canadian Pacific [rail] road have also shown a decided disposition to render material financial aid in perfecting this great work.

“At present those most intimately connected with the scheme are unwilling to divulge their plans, but it is stated on reliable authority that preliminary surveys of several proposed routes for this contemplated canal have already been made, and the feasibility of the project has already been vouched for by eminent engineers. One of the plans under consideration is to tap Lake Michigan at a point near Michigan City or New Buffalo, and to run the canal directly eastward to Toledo, O. Another plan, which also has a number of influential supporters is to strike Lake Michigan at Benton Harbor and thence run in a northeasterly direction to Detroit. Either of these canals would be about 180 miles long, and when it is considered that it would save about 700 miles of lake [travel] which is at present necessary to reach eastern points, its importance to the commercial and financial world cannot be overestimated. The route from Michigan City to Toledo would, it is claimed, prove far more advantageous to Chicago than the other route, and hence is being more strongly urged by those whose interests are countered here. On the other hand, it is stated that the Canadian Pacific railway would be largely the gainers by the route to Detroit.

“There is yet another proposition under consideration which may, it is stated, prove satisfactory to all parties concerned, although it would involve a greater expenditure of money. This idea is to adopt the Michigan City and Toledo plan, and to construct a branch canal [along the route of the Illinois and Michigan Canal.]

“Ft. Wayne is situated at the lowest point along the summit of the great ridge through Ohio, Indiana and Michigan, which separates the waters which run to Lake Eire and those which flow to the Gulf of Mexico. [Elevations above sea level for towns along the crest of this ridge are given in the article.]

“The summit levels for the canal will be: Fort Wayne and Kankakee. The lowest levels will be Toledo,

Logansport, and Like Michigan. The Maumee and Wabash [rivers] will furnish the water supply from Toledo to Logansport; the Tippecanoe, Monon [?] and Kankakee [rivers] from Logansport to Lake Michigan.

“The distance from Chicago to Toledo by this route is shorter than by any other practicable line. The work to be done will be the revival and enlargement of the Wabash and Erie Canal from Toledo to Logansport, and the construction of a new line to the Tippecanoe, Kankakee and Lake Michigan. On this new section no elevation above 750 feet from sea level will be encountered, and nowhere will the excavation required exceed one hundred feet.

“In the comprehensive improvement of our means of transportation this plan will serve the double purpose of connecting Lake Michigan with Lake Erie and the Gulf of Mexico. The improvement of the Wabash, Ohio and Mississippi would naturally follow the opening of the canal from Lake Michigan to the Wabash.”

This proposal was never carried out, but proponents of a ship/barge canal through Indiana did not give up. Still another proposal was put forth that had residents of Rochester, Indiana excited since this canal would come to their town. The Rochester Sentinel of November 21, 1907 reported:

1907

“A Gigantic Canal—Plans are now being made by the government for the opening of a gigantic canal which will connect Toledo and Chicago. Frank Leverett, of Ann Arbor and M. B. Taylor, both members of the United States geological survey, are preparing a joint monograph for the government, the former dealing with the glacial period in Northern Indiana and the southern peninsula of Michigan and the latter giving a glacial history of the great lakes. Both of these gentlemen are fully prepared to give accurate information concerning the soil characteristics and altitudes of the proposed canal route.

“Mr. Taylor and Mr. Leverett agree on the following route:

From Toledo to Ft. Wayne using the Maumee. Fort Wayne is 177 feet higher than Toledo. Several locks would be required in the river.

From Ft. Wayne, passing through Huntington, to Rochester, on a perfect level. This stretch would the ‘summit level’ of the canal. Four rivers would empty into this ‘summit level,’ the St. Mary’s, the St. Joseph, the Tippecanoe and Eel rivers.

From Rochester to Bass Lake, with a thirty foot drop in the lock at Rochester.

From Bass Lake to Deep River, south of Hobart. Here two locks would be required, one of forty feet and another of sixty feet.

From Deep River to Calumet River, which empties into the lake at Chicago, with this great

improvement boat traffic would begin much earlier than is can commence now—that is, that portion which must pass by way of the straits of Mackinaw—and it would continue much later in the fall. This route would cut off about 450 miles on the water trip between Toledo and Chicago. It is about 700 miles by water between the cities now. The canal would be about 250 miles in length.”

1908

The Rochester Sentinel of January 29, 1908 reported: “There is a movement on foot to build a ship canal from Toledo to Chicago or perhaps to Michigan City. The gentlemen who have undertaken to locate the line of the canal have followed the summit level at Ft. Wayne, the lowest summit level between Toledo and Chicago, and this leads us to Rochester as the west end of this level.

We feel that the proposition we have in hand is feasible and is practicable. We have water enough for a ship canal 24 feet deep. This canal will cut off 450 miles between Chicago and Lake Erie. It will be an open waterway practically the year round. We are at Ft. Wayne 175 feet above Lake Erie and 170 feet above Lake Michigan.”

The article advises citizens of Rochester that there will be a meeting in Ft. Wayne within a few weeks. They want to have delegates from Toledo, Napoleon and Defiance, Ohio, and from Huntington, Wabash and Rochester, Indiana, and Chicago. Rochester is to appoint delegates to this meeting.

The Rochester Sentinel of February 5, 1908 reported that an enthusiastic meeting had been held the night before in Huntington concerning the ship canal and Enoch Myers, Arthur Metzler and J. E. Troutman had attended. Present was Hon. Perry A. Randall of Ft. Wayne, acting president of the Indiana Branch of the National Harbor Congress, who spoke about the proposed project. He talked about a speech given in Memphis, Tennessee, by President Teddy Roosevelt in which Roosevelt “referred to the importance of our country looking after the construction of more inland waterways to keep in line with the march of progress of other countries, England, France, and many other countries which have profitably spent vast sums of money in canalizing their streams or building canals and thereby cheapening transportation so much that we could not compete with them.”

Randall said after careful measurements had been made the only feasible route for the canal would be up the Maumee River to Ft. Wayne, thence to Huntington and down the line of the old Wabash [and Erie] Canal to near Roann and on down the natural waterway by way of Gilead and Rochester, to a point on the Tippecanoe River south of Lake Maxinkuckee and thence to Indiana Harbor or south Chicago and there meet canals already constructed. Mr. Taylor, who was preparing a pamphlet to educate people on the matter, said this route would require but three locks and the summit level would be one hundred and ten miles long.

Mr. Taylor urged Rochester to form a branch organization such as Ft. Wayne, which had over six hundred members, and Huntington had done to educate them and to bring pressure on congressmen to pass the bill now pending in Congress to make the survey for this waterway and make an appropriation for such purposes.

Recently the State of New York had made an appropriation of one hundred million dollars to deepen and improve the old Erie Canal and had asked the Government to make an additional appropriation to make it a ship canal to the lakes.

The Chicago Tribune in 1908 said “The Toledo, Fort Wayne and Chicago Deep Waterway association has a grand scheme for a canal connecting Lake Michigan and Lake Eire. This canal will save 800 miles of journey up and down the lakes….The highest point on this route will be but 177 feet above the level of Lake Erie and this summit level will extend for a distance of 100 miles, thus allowing the boats to shoot along for a 100 mile stretch without being hindered by locks.

“The route worked out by this engineer has a greater supply of water on this summit level than any other previously proposed. This is important, for it the canal proves a success it will be traveled by a large number of boats every day, and thus will keep the lock working overtime. Each time the lock is opened to allow a ship to pass through a certain amount of water will be needed, and unless this can be supplied by feeders on the highest level of the canal it would have to be pumped in, thus increasing the cost of operating.”

The article went on to say that constructing locks is a major cost in constructing a canal. This route not only would be cheaper to construct, but the absence of locks would allow boats to make faster time and decrease the cost of operating.

“Lyman E. Cooley, the well-known engineer of the Chicago drainage canal, thinks this is the best route which has been planned. He says that the Maumee River could be used all the way from Toledo to Fort Wayne and about twenty miles of the Tippecanoe River can be used below Rochester.”

1909

Although Indiana was concentrating on a ship canal between the lakes, a great canal system was still being sought in Congress by the Rivers and Harbors Committee through a passage of a bill to provide for a survey of an Atlantic coast canal, a canal skirting the Gulf of Mexico, a canal connecting the great lakes with the Ohio river and a canal connecting Lake Erie with Lake Michigan. According to an article in the Columbus Evening Republican on February 3, 1909, a survey of the lakes-to-the gulf waterway through Illinois and by way of the Mississippi was already in progress. It said that the lakes-to-the-Ohio canal probably would extend from Toledo to Cincinnati and that Representative Gilhams, of the Ft. Wayne district, was hopeful that the bill would provide for a survey of the proposed canal from Toledo to Chicago by way of Ft. Wayne.

Seven months later the Kendallville Daily Sun reported on November 9, 1909 that the planned canal from Chicago to Toledo would be discussed at a convention in Fort Wayne by the Toledo, Fort Wayne, and Chicago Deep Waterways association. It said, “Chicago, Cleveland, New York, Cincinnati, Toledo, Defiance and other cities will have representatives at the convention. United States Senators Beveridge and Shively of Indiana will be among the speakers.

“The Michigan and Erie canal, as planned from Chicago through Fort Wayne to Toledo, will be 270 miles long and 400 miles shorter than the present all water route from Chicago to Toledo by way of the great lakes.” Note that this article gives a name to the ship/barge canal.

1914

In 1914 B.J. Griswold and C. A. Phelps published The Griswold-Phelps Handbook and Guide to Fort Wayne, Indiana, that sold for 25 cents. It relates how a meeting was announced on November 7, 1907 and held on November 16, 1907 in Fort Wayne pertaining to the proposed development of the Maumee River from Fort Wayne to Lake Erie for navigation purposes. It tells about the roles P. A. Randall and Judge Robert S. Taylor played in promoting the canal and the pamphlet Taylor printed and spread throughout the central states. It then reports: “By 1910 the government became so thoroughly interested in the movement that a mass meeting was held at Princess rink, attended by men of national repute as the chief speakers. Through the efforts of Congressman C. C. Gilhams, and later, Congressman Cyrus Cline, much good was accomplished in Washington tending toward national assistance. Capt. Charles Campbell, of New York, engaged to assist in pushing the project, accomplished much good by securing the co-operation of commercial interests in Chicago and Toledo. Preliminary surveys were made under the direction of the United States Army department, the work being done by Col. John Mills and Col. G. A. Zinn. In November 1911, the National Waterways commissions visited the region, and conducted a public hearing in this city. The commission, composed of Senator T. E. Burton, Hon. D. S. Alexander and Hon. J. A. Moon was accompanied by army engineers. Following the visit, a thorough survey was ordered and completed by army engineers. Subsequent events have given every assurance that the great project is to become a reality. Chief among the claims for the construction of the canal are the following: Shortening the water route between the east and the west, and thus reducing the cost of freight transportation. Solving the shipping terminal problems which the railroads are unable to do because of the difficulty of securing proper terminals in the large cities on account of the prohibitive prices of

ground. The impossibility of railroads constructing additional east and west lines to care to the ever-increasing demands of shipping interests. The lengthening of the water-route at an earlier date in the spring and continuing to a later date in the fall than is now possible by the north water route between Toledo and Chicago by way of Detroit River, Lake St. Clair, Lake Huron and Lake Michigan. The cost of the completed canal is estimated at from $30,000,000 to $40,000,000.

“Among those not already mentioned and who have given of their time, energy and money to further the canal project may be mentioned T. E. Ellison, Maurice Niezer, C. R. Lane, Senator Shively, Senator Kern, Congressman J. A. M. Adair and Senator S. B. Fleming,”

Using many of the same arguments as those used earlier for building the now defunct Wabash and Erie Canal, proposals were made for several of these larger ship/barge canals. Bills were passed in Congress over the years, surveys made, and costs of construction continued to rise. It seems that eventually wiser minds prevailed. The proposed ship canal through Indiana between the Great Lakes and the one through Indiana to Gulf of Mexico were never built. Later the Ohio River was canalized and has become our ship/barge canal.

CANAL NOTES 10

SPY RUN BLUFFS

TOM CASTALDI

telegraph lines were put atop the towpath. The St. Joseph River is on the right.

Spy Run Extended, Fort Wayne’s road that follows the Saint Joseph River to Johnny Appleseed Park, was not always a level, winding and pleasant roadway. In the 1830s, it was a bluff overlooking the river and in the path of a channel being dug to feed water to the Wabash & Erie Canal’s main line.

Think of the job it would be for bulldozers and road graders to move a bluff as big as a hill out of the way. In 1833, they did it with shovels, mules, picks and buckets.

Hundreds of immigrants from Ireland came to this county taking on the job of cutting through bluffs, swamps, trees, roots and bogs. Working with beast and hand tools showed the way cutting through an untouched wilderness from Fort Wayne to the Ohio River at Evansville.

The canal had its day in the sun for a few short years, but it began drying up after the railroads made tracks along side the waterway in the mid 1850s.

Spy Run’s bluff was just one obstacle of hundreds of tons of earth that had to be moved without the help of machines. The work was done by hand and with sheer determination.

Now power lines hang gracefully from towers standing on the towpath where mules once pulled on long towlines. Spy Run Extended served fast moving car and bus traffic where once passengers and cargo boats moved slowly along, because hard working canal diggers shoveled away a bluff that stood in the way.

Frank Bash Interviews Citizens Who Remember

the Wabash and Erie Canal

Margaret Griffin, CSI Director (Ft. Wayne)

Part 1

Because of one journalist’s determined efforts a century ago, we know many details about the Wabash and Erie Canal between Fort Wayne and Huntington. Frank Sumner Bash ran a weekly column from 1922 to 1931 in the Huntington Herald based on interviews with longtime residents of the county.

A man named Anthony Weber told Bash he could remember walnut wood strewn and piled up high on canal banks as far as the eye could see. Logs were partly squared with a broad-ax and the ends painted with red lead to guard against “air checking.” Marked with the brands of the owners, they would be tied together into a raft to float down the canal to Fort Wayne or Toledo.

Eighty-six year-old pioneer Amanda Cain told him that “back in 1849 it was a sight for us to watch the canal boats winding their way towards Toledo with wheat and corn to make flour and meal for people to make bread.”

Bash wrote that as children, Wesley and Mary Hawley passed their time watching canal barges, mule drivers, packets and the state boat from their home (close to present-day Division Street and College Avenue), gazing at operations in a nearby boatyard as well as fishing in the canal and Flint Creek.

Matilda Nuck Rausch, born in 1840, remembered playing with Indian children and understanding their language plus English and German. She spoke some of the Miami words for her interviewer. Also she told about the day the Miami people left for the west on canal boats at the Forks of the Wabash. “They cried, groaned, moaned, clasped their hands, and even picked up handfuls of earth which they reverently put in their pockets as a token of the land they loved…”

While Mrs. Rausch’s parents came by an all water route from Germany, Mrs. Jacob Kettering’s parents began in Switzerland. They traveled by canal in the U.S. One of her earliest memories was wolves howling at night as they slept in their cabin.

Dr. Sylvanus Koontz came with his family across Lake Erie to Toledo, then on the canal to Roanoke. Their tickets called for transportation, room and board. He said that if table supplies happened to give out, the captain would help himself to bucketfuls of sugar and molasses from barrels that wholesale houses were shipping to merchants. The “old folks” slept on cots and berths, but youngsters including himself swung in hammocks next to the cabin roof.

Mary Shearer Pinkerton’s father owned an elevator north of the canal where the Huntington Theater stood at the time of the interview. He owned a fleet of canal boats to ship his grain to market. When the canal was abandoned, he rented the boats to people to live in. Then he sold them and they were towed to Cincinnati to be used on the Ohio River.

Elizabeth Kramer, 97, with her husband owned the freight boat Eldorado which ran between Toledo and Terre Haute. The men and mules worked six-hour shifts. Mrs. Kramer cooked for the crew, once serving a 20-pound cabbage bought at a county fair.

Another lady who was a cook on a canal boat was Mrs. Clara Shaughnessy, who married a pilot. She and her husband worked on the Sam Buchanan, a boat named after a Huntington businessman. They also worked on a dredge boat that removed sandbars and made repairs on the canal; these boats stayed in some locations for several weeks. After their days on the canal were over, they took up residence in Huntington, her husband working at one of the local sawmills for many years.

Charles Foster, 93, got a job on a canal boat in Lagro for $13 a month. He remembered dry spells when the water wasn’t deep enough for boats to float. “Boats would be strung close together in every town,” he said, with a fight about every five minutes between boatmen.

Lydia Shock, 84, told that she came with her mother and sister by canal to Huntington, but her father came overland with horses, cattle and sheep. The sheep were later all killed by wolves in the vicinity.

“Are you the fellow that writes pieces for the paper about old folks?” one woman asked as Bash sat on her front porch.

For ten years, he did just that. Authors of canal articles and books have used the primary source information he found, which tell us not only about a major change in U.S. transportation but a way of life long gone and lost to us, if not for his devoted writing.

There will be more about his interviews in The Tumble, thanks to a 900-page volume of articles which historian Jean Gernand compiled in 2016.

Information from Find-A-Grave

Anthony Weber (21 Jan 1853-20 Jul 1936), wife Freelove C. Weber, Mount Hope Cemetery, Huntington County, Indiana

Amanda Hawley Cain (7 Jan 1837-24 Jul 1923), husband Freedom L. Cain, died in Huntington, Indiana, burial?

Wesley Willard Hawley (1848-1926), Mount Hope Cemetery, Huntington County, Indiana (brother of Amanda Cain)

Mary Hawley ( ) (sister of Amanda Cain)

Matilda Nuck Rausch (1841-2 Dec 1940), Mount Calvary Cemetery, Huntington County, Indiana

Dr. Sylvanis Phillips Koontz (25 May 1844-1 May 1925), Glenwood Cemetery, Roanoke, Huntington County, Indiana

Mary Shearer Pinkerton ?

Elizabeth Kramer ?

Clara A. Overholtser Shaughennessy (31 Mar 1842-2 Mar 1929), husband John M Shaughennessey, Mount Hope Cemetery, Huntington County, Indiana

Charles Foster (14 Jun 1830-28 May 1925), Mount Calvary Cemetery, Huntington County, Indiana

Charles Foster came to the US from Germany, first working in the anthracite (hard coal) mines of northeastern Pennsylvania. In 1852, he and his brother Peter (#128968717) and Peter’s wife Elizabeth (#128968763) moved to Huntington. Charles worked at a number of trades, including on the Wabash & Erie Canal; with Pete he quarried limestone and burnt lime, providing material for the construction of the Cathedral in Fort Wayne and the Catholic church on Cherry Street in Huntington. In 1862, Charles obtained the contract to rebuild the culvert where the Canal crossed Silver Creek west of the Forks of the Wabash; this stone arch culvert still stands today (2023). He also operated a brick yard in Huntington, and 1872 built the new St. Patrick’s Catholic Church in Lagro. {Credit is due to F.S.Bash whose article appeared in the 6 January 1923 edition of the Huntington Herald, based on his interview of Mr. Foster when he was 93 years old.}

Lydia Freehafer Shock (8 Feb 1840-29 Mar 1927), husband Samuel Shock, Shock Cemetery, Huntington County, Indiana

The Fugitive Slaves

Tom Castaldi, CSI Director (Ft. Wayne)

The following story took place in 1834 when the Wabash & Erie Canal was beginning construction and the first sections were yet to reach Huntington from Fort Wayne in 1835.

“The Fugitive Slaves,” History of Jay County, Indiana, (1864) by M.W. Montgomery

“Samuel, and B.W. Hawkins carried the mail by turns, from Winchester to Fort Wayne, by way of Deerfield, Hawkin’s Cabin, New Corydon and Thompson’s Prairie. One evening in the month of February, 1834, Samuel reached his mother’s cabin, on his return from Fort Wayne, while a heavy snow was falling. It was already about ten inches deep and continued to fall so fast that objects could be seen only a few rods from the door. It was a dreary night out doors, but the family were enjoying themselves around a comfortable cabin fire. A loud rap was heard at the door, and, upon its being opened, eight negroes, six men and two women, presented themselves and begged for a night’s lodging. Their request was granted. The men were all common looking negroes, except one. He was tall, broad-chested, very muscular and well proportioned. He possessed affable manners, and an intelligent countenance, and was the leader of the company. One of women was about twenty years of age; the other was a mulatto, and wife of one of the men. She was thinly clad and in feeble health. The canal through Fort Wayne was then being dug, and was attracting laborers from great distances. This company said they were going to work on this canal. The next morning they started on their way northward and Samuel Hawkins went on to Winchester with his mail. There he learned that the negroes were fugitive slaves, and met their pursuers, who had been waiting for him. They asked if he had “met” the slaves. He replied that he had not. This was technically true but was designed to deceive the man-hunters. There were then two routes from Fort Wayne to Winchester: one by way of the Hawkins’ Cabin and New Corydon, the other by Brooks’ and the Godfrey Farm. Supposing, from Samuel’s reply, the fugitives had not gone this road, the slave-holders took the other route, feeling certain that they were on the right track. The reward for the apprehension of the slaves was $1,000, and Samuel Hawkins, by simply giving the information in his possession, might have taken the money. It was a great temptation for one so young and needy, but he did not for a moment entertain a thought of betraying the fleeing company. He said if they would undertake that long, dangerous and wearisome journey on foot and through the deep snow, to gain their “Liberty,” he could not find it in his heart to betray them into bondage. He had the feelings of a man in his bosom and acted accordingly. When the pursuers took the wrong track, he hastened to return, and overtook the fugitives at the Wabash where New Corydon now stands. The snow was so deep, and progress on foot so difficult, that they had only been able to reach that distance.”

It goes on for a few lines saying that Hawkins when seeing the feeble woman straggling behind the others, “Dismounting from his horse, the fallen woman was placed up the saddle, and he aided her as far as his time would permit, and, giving them directions, he returned to his route and never heard of them afterward. Perhaps they were George and his company, described by Mrs., Stowe in Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

In an article by Rebecca Biggs that was in the February 5, 2020 issue of the Logansport Pharos Tribune newspaper she wrote, “It took two Supreme Court cases to end the ‘peculiar institution’ of slavery in Indiana.” In her “Historical timeline of slavery in Indiana” she noted: “In 1820 Indiana Supreme Court freed all remaining slaves; 1821 the Indiana Supreme Court put an end to indentured servitude, being used as an end run around the slavery ban, however, by 1830 the U.S. Census showed three slaves residing in Orange, Decatur and Warrick counties.”

Feeder Canal Swing Bridges

Craig Berndt, CSI member from Fort Wayne, found a bid list for the Ft. Wayne, Jackson & Saginaw Railroad in the Fort Wayne Gazette of April 1869 that details the swing bridges over the St. Joe Feeder Canal. About ⅔ of the way down the list it gives the bridges that crossed the feeder. The article says:

“Evans to the Fort Wayne Gazette detailing the letting of contracts on the Fort Wayne, Jackson and Saginaw Railroad in Allen county. The work is going rapidly forward, at the south end of the line. The letter explains why the work has not been continued in this county:

“Messrs. Editors.—The engineers’ and contractors’ offices have been alive for the past two days with bidders for the different portions of the work. A number of parties were present from other States as competitors for the work among whom were T. H. Hamilton and S. O’Neil, Toledo, Ohio; Durfee & Vanwry, Noblesville, Ind.; T. B. White & Sons, New Brighton, Pa.; Underhill & Lowry and Wheelock, McKay & Goshorn, Jackson, Mich.; H. D. Clark, Delphos, O.; N. C. Hall, White House, D.; J. T. Willey & Co., Bay City, Mich.; and a multitude of home contractors for construction work. &c.

“The successful bidders for River bridges were Wheelock, McKay & Goshorn.

“For Swing Bridge, canal—not let.

“For Swing Bridge feeder—not let.

“For Bent and Pile Bridges—Gen. R. Barlett

“For Masonry of River Bridge—Wm. Paul.

“For construction, commencing at north line of county of sections 82, 83 and 84—A. J. McDonald & Co.

“Sections 85, 86, 87 and 88—not let.

“Sections 89 and 90—J. C. & John Pakewalk.

“Section 91—John Corcoran & Co.

“Sections 92, 93 and 94—A. J. McDonald & Co.

“The contractors propose to have the road ready for the iron, in Allen county, by the 1st of October next. It is a favorable comment upon our city that we have contractors competent to compete with parties from other places of greater pretensions.”

Craig has found a description of the canal bridges in another report, which reads something like this:

Each bridge had two parallel I beams across the canal with a rail atop each beam (“stringers”). Smaller beams tied the big beams together at certain intervals to keep the rails in gauge (“cross beams”).

Both stringers were hinged at the same end and the other ends were tied to the track on the other side of the canal. To open the bridge, the cross beams were removed and the stringers were swung left or right together parallel to the canal bank, thus opening the canal for passage.

The default setting was the swing bridge open for canal traffic, and closed only when a train needed to cross.

The Hagerstown Extension Of The Whitewater Canal

Phyllis Mattheis, CSI director (Cambridge City)

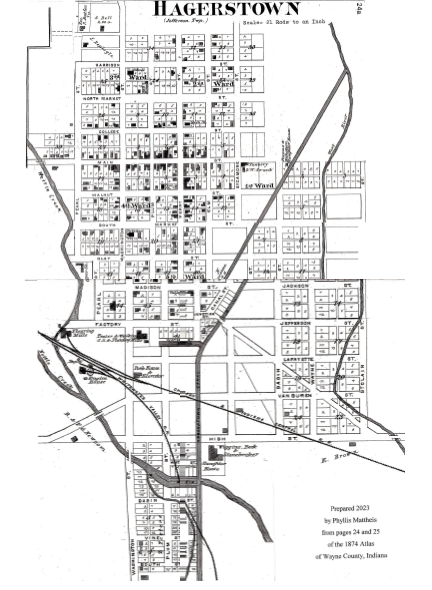

As the Canal Society of Indiana chooses where to place signs along its canal routes, we try to identify sites that were previously unknown as well as those that are well known. Phyllis Mattheis is studying the Hagerstown Extension for sign placement. Below is a map and description of what she has found.

MAP OF HAGERSTOWN, INDIANA TAKEN FROM THE 1874 ATLAS OF WAYNE COUNTY

SHOWING WHERE THE WHITEWATER CANAL WATER IS TAKEN FROM THE WEST RIVER NEAR THE NORTHEAST CORNER OF THE TOWN. WATER ALSO COMES FROM NETTLE CREEK AT THE SOUTH EDGE.

The canal crosses the south part of Hagerstown at an angle. There are two basins for loading and unloading boats. The north basin is a half block south of Factory Street and the south basin is where Nettle Creek furnishes water from the west, south of High Street.

The two rivers join just south of Hagerstown to form the West Branch of the Whitewater River, which flows south and through Cambridge City, where the canal was planned to end at the National Road. Merchants and farmers in the Hagerstown area paid to extend the canal 8 miles north to their town, which became the northern terminus of the Whitewater Canal when the Hagerstown Canal was completed in 1847.

The fall from Hagerstown to Lawrenceburg on the Ohio River was 491 feet, requiring 56 locks to lower the southbound canal boats and raise the northbound boats, which were pulled by mules or horses. After all that manual effort and huge investments, the canal for boats had a life of only about 20 years, but it developed settlement and commerce in the eastern side of Indiana. Railroads were coming into the are by 1853 and operated all year long. Canals froze over in the cold months preventing traffic, but furnished ice for the ice houses. The canal water was used by mills and factories along the 76 mile route, even into the 1950s, especially in the Connersville area. So it became a hydraulic canal furnishing power.

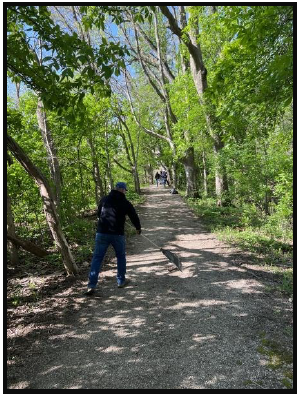

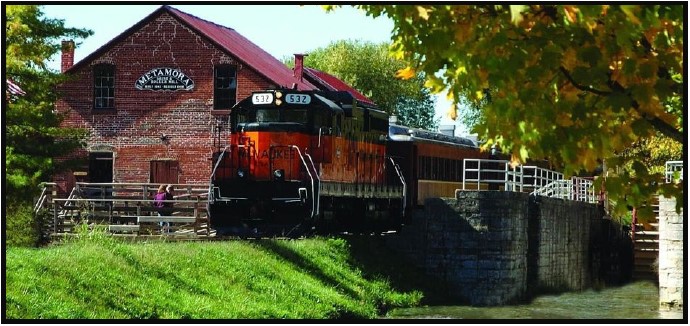

A dam near Laurel feeds water into Metamora, where there is a mill. A walking trail is being developed from the dam into Metamora and beyond by volunteers.

No Compromise!

Carolyn Schmidt

An interactive Mystery/History Dinner Theater was held on April 14-16 at the Antwerp Global Methodist Church in Antwerp, Ohio to raise funds for a mural to be painted on the side of the Friend Flooring building in downtown Antwerp. It was a resounding success with Friday evening’s attendance being oversold for more than 100 attendees and over 39 participants in the cast or as servers, etc.

No Compromise! The Story of the Reservoir War of 1887 was an accurate historical presentation of what occurred that year in April a long time after the Wabash & Erie Canal in Paulding county, Ohio was officially closed, the Six Mile reservoir had become a source of ague and miasma, and the remaining canal bed from Antwerp to Defiance was only used to float logs cut from the Great Black Swamp into Defiance. Citizens of Antwerp wanted the reservoir to be destroyed as they were becoming ill and dying from malaria transmitted by the ceaseless mosquitos. The sounds made by these relentless insects were heard throughout the play and each table had its own smudge pot, which steamed to ward them off.

The ladies at the local Bargain Bin had just been donated a scrapbook with articles about the reservoir war and, while looking through it, told the audience of what had happened at the time. They were very humorous when making jibes at the cast members and others in the audience. The cast members also interacted with the audience.

A four course dinner prepared by Grant’s Catering of Antwerp was served between the four scenes of the play. Men and women in period dress at each table quickly brought out the hot dishes. While it was eaten, attendees were asked historical questions about Antwerp and Paulding county.

The play revolved around 1887 at Antwerp’s Six Mile Reservoir; Tate’s Landing; Junction and Defiance, Ohio; Camp Dynamite; the Knoxdale Train Station and the present day area. It showed how the people of Antwerp felt about the capitalists of Defiance, who tried to keep the reservoir and canal open. Every time Defiance was mentioned, they spat at the town.

The chief villain who led the campaign to keep the canal open to Defiance was C.A. Flickinger, played by Jarett Goedeke, CSI’s newest elected director. With his twinkling eyes, handlebar mustache and a huge black barbell, the Bargain Bin ladies thought he was really cute even though he was their enemy. He and his cohorts were always spying on Antwerp and keeping track on what was happening at the reservoir.

The plot to destroy the reservoir was led by Ona S. Applegate and Worden “Henry” Sperry, the later had a gold tooth that gave away his identity when seen behind his mask while dynamiting the reservoir. Even the women of the town, who were not the greatest seamstresses, and one, who was always tipsy, banded together and created a “No Compromise” banner to support their husbands.

After several attempts to destroy the reservoir Governor J. B. Foraker sent out the militia to stand guard. This did not deter the dynamiters, who made further forages. On the night of April 25, 1887 two to three hundred of them overcame the guards, split up into groups with one group blowing up the reservoir and reservoir lock and another going to Tate’s landing to blow up that lock. Foraker sent additional militia and a Gatlin gun, but they were too late, the dynamiters had fled to Knoxdale.

Days later the Governor arrived, agreed the reservoir needed to be drained, and said he would have a bill passed to end it. Antwerp then held a Grand Jollification on July 4, 1888. Although Sperry was identified and briefly held in arrest, none of the dynamiters were ever prosecuted. They were thought to be heroes by their community.

CSI members who attended the play were Jim Crouse; Jerett Goedeke; J. K. Porter-Gresham; Sue Jesse; Melissa Krick; Jane Nice, the author of the play; and Bob & Carolyn Schmidt. If you attended and were not mentioned, please notify CSI headquarters: indcanal@aol.com.

It was inspiring to see all these community members thoroughly enjoying themselves while working together for the mural project. This play was a win, win for Paulding county.

Jerett Goedeke has written a book about the reservoir war. It will be published in the third quarter of 2023. We look forward to reading it.

Bodine’s Canal Boat Model

Photos by Anne Bodine

After finishing his latest model, a canal lock, Terry Bodine, CSI member from Covington, Indiana began work on a model canal boat to fit within the lock. It won’t be long and Terry will have this project finished.

Signs Delivered

On Monday, April 10, 2023, Bob and Carolyn Schmidt picked up six canal signs from CDS Signs in Sharonville, Ohio. About an hour later they delivered 4 of the signs to Shirley Lamb at Brookville, Indiana to be placed on the trails and at canal sites. Two of them were 4 ft. x 6 ft. and were for Butler Run Culvert and the Brookville Canal Boat Basin for the Whitewater Canal. The other two were 2 ft. x 4 ft. and were for Simonton’s Lock No. 28 and Laurel Lock No. 30.

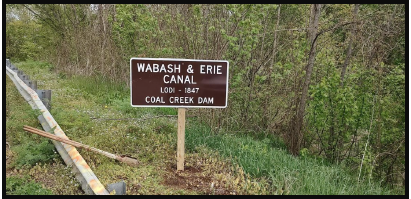

On April 16, 2023 Bob Schmidt met Troy Jones, CSI member from Clinton, Indiana, at the Kerr Lock in Lagro, Indiana to deliver two 4 ft. x 6 ft. signs for placement on the Wabash & Erie Canal at the Raccoon Creek Aqueduct south of Montezuma and at the Lodi dam on Coal Creek in Parke county.

Jones Erects Signs

After meeting Bob Schmidt in Lagro, Indiana to pick up the signs for Parke county, Troy Jones created a frame behind each sign to stabilize it. Then on Tuesday May 2, 2023 he erected the signs for Big Raccoon Creek aqueduct near Armiesburg, Indiana and Coal Creek Dam at Lodi, Indiana. The spelling of Raccoon will be corrected in the future. We thank Troy for all his work.

Note that some stones from the aqueduct abutment can be seen at the edge of the creek and the foundation timbers can still be seen in the creek bed. The aqueduct had two piers and two abutments. It was taller than the aqueduct on Sugar Creek, but much shorter in length.

A dam was placed in Coal Creek to back up creek water to create a slackwater pool for canal boats to cross the creek. The dam was located to the west of the road toward the Wabash River.

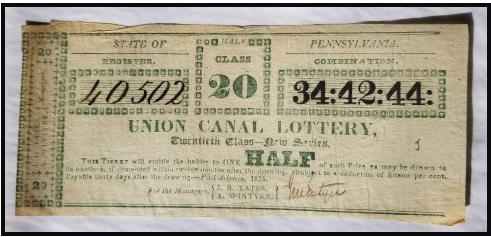

Union Canal Lottery Ticket

Neil Sowards, CSI member from Ft. Wayne, found the above Union Canal Lottery Ticket on e-Bay. This type of ticket was sold to fund the canal. It says:

STATE OF PENNSYLVANIA

Register 40502 Half Class 20 Combination 34: 42: 44:

UNION CANAL LOTTERY,

Twentieth Class—New Series

This ticket will entitle holder to one HALF of such Prize as may be drawn to its numbers, if demanded within twelve months after the drawing. Subject to a deduction of fifteen per cent. Payable thirty days after the drawing.— Philadelphia 1825

For the Managers { J. B. Yates }

{A. McINTRYE}

On the left hand side it says:

20 J. B. YATES } Managers 20

A. McINTYRE}

It is signed by McIntyre.

There is also a J. on the face of the ticket.

Donations To CSI Archives

The Canal Society of Indiana has a collection of canal books, photos of canal sites and canal postcards at CSI headquarters. From time to time we receive the collections of our old publications, books, photos and postcards from members who are downsizing or have passed away. We add any of these items that are different from what we already have to the CSI collection. The rest are given to members as door prizes or sometimes sold to fund our projects. We only offer them to those who have a keen interest in canals. Recently we have received the collections of:

Jerry & Mary Ann Getty – Donated by their children, over 100 canal books and booklets, maps, pictures, interurban books and resource material, a canal boat model, and Civil War books

Neil Sowards – Duplicate photo copies of Ohio canal postcards

Allen Vincent – Donated by Scott Vincent, 25 canal books, maps, past CSI publications, etc. and Civil War books

We thank them for their donations to help keep the interest in canals alive.

News From Delphi

| Delphi’s Canal Park Then & Now | Historic Skills Workshops |

| Earth Day Volunteers | Volunteers Replace Loom House Log |

| Spring Cleanup | $2,500 Grant For Website |

Delphi’s Canal Park Then & Now

In March 2023 the Carroll County Wabash & Erie Canal Association found a photo album belonging to founding member Roseland McCain, one of the spirited pioneers who helped transform the Wabash & Erie Canal in Delphi from an eyesore to a cultural and recreational treasure. Take a moment and compare these photos, dating from 1971-1990 to photos taken recently. Delphi volunteers have worked together for decades to preserve history and develop this recreational park. Pictures courtesy CCW&EA Facebook page.

Earth Day Volunteers

Canal Park and its southern historic trails in Delphi were cleared of brush, timber, and several bags of trash on Earth Day, April 22, 2023 by energetic, expert and well-equipped volunteers from Delphi’s Future Farmers of America. Following all their hard work they went to Pizza Hut and had their lunch donated. These partners help keep Delphi’s trails and canal park beautiful!

Spring Cleanup

On May 6, 2023 from 9 a.m. until Noon volunteers gathered at Canal Park for a spring cleanup day of brush, sticks and debris in Pioneer Village and its surrounding trails. They were treated to a free lunch provided by Delphi Psi Otes at the Speece picnic shelter. This was followed by a narrated nature hike to Founders Point at 1 P.M. with David McCain, who shared with them the natural marvels along the towpath.

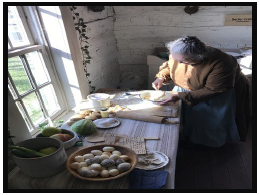

Historic Skills Workshops

This year historic skills workshops were offered at Canal Park. Bobbin lace & tatting -Carolyn Regnier, Paper making – Linda Cooper, Broom & basket making – Bev Larson, Hearth cooking & hand quilting – Becky Crabb, and Coopering -Peter Cooper. A notice was sent to all CSI members about these classes since most of them were held prior to this issue of “The Tumble.” We hope some of you enrolled.

Volunteers Replace Loom House Log

The Loom House at the north corner of Pioneer Village in Canal Park had a new log installed by the Monday-Wednesday-Friday Crew of volunteers. They had to remove the old log, brace the structure, trim a new log to fit, insert it, calibrate the door frame, and add chinking between the logs.

The Wabash Weavers Guild gives weaving demonstrations every Saturday afternoon from 1-4 p.m. during the Canal season May 20-September 9 in this building.

$2,500 Grant For Website

Carroll County Wabash & Erie Canal Association has received at $2,500 grant from Visit Lafayette-West Lafayette to develop a functional and informative website. Canal Park hopes to update the website with online reservations for canal boat tickets, museum tickets, Reed Case House tickets, and RV/tent camping. The website will also be streamlined.

Whitewater Canal News

Whitewater Canal Historic Site’s New Manager

As of April 17, 2023, Joey Smith, a Hoosier native, became the new site manager at Whitewater Canal State Historic Site (ISMHS), one of 12 properties in the Indiana State Museum and Historic Sites statewide museum system. He replaced Jay Dishman, who retired in February after holding the position for 35 years.

Smith graduated from Wabash College in 2007. He began his career as an exhibits specialist at ISMHS building, installing and maintaining museum exhibits using carpentry and welding. He also was the community marketing coordinator at ISMHS, with responsibilities for social media, earned media and promotional content for the museum’s historic sites.

For the past four years he has been in the craft brewing industry, serving in various leadership roles, including distribution sales manager at Guggman Haus Brewing Company and director of logistics at Metazoa Brewing Company. He is an experienced marketing professional, serving as multimedia and events manager, as well as sponsorship and street team manager for NUVO, a cultural media company based in Indianapolis.

CSI is looking forward to working with him in keeping us informed as to what is happening to the Whitewater canal, locks, aqueduct, etc. in Metamora. Welcome aboard!

Earth Day Whitewater Canal Trails

Volunteers for the Whitewater Canal Trail participated in their Earth Day event on April 22. 2023 to clear the trails of brush and debris. After all their work, Moster Turf let them use its barn for a great barbecue from the “Smokin Butts” food truck, donuts from Trout Unlimited and the Blue Umbrella for cinnamon rolls.

The trails are now ready for early spring hikes.

Whitewater Canal Scenic Byways Prepares To Open Museum In Gateway Park

The Visitors Pavilion in Gateway Park in Metamora, Indiana was prepared to be opened for the season by volunteers from the Whitewater Canal Scenic Byways. They took the protective covers off of the acrylic cases donated by CSI that house the models of a mill and a lock that were built by Paul Baudendistel. This museum is a good place to start your canal adventure of the Whitewater Canal.

Lock 24 Prepared For Waterwheel

Preparations for putting a new waterwheel into Lock 24 of the Whitewater Canal in Metamora at the State Historic Site neared completion when these photos were put onto Facebook. The last issue of “The Tumble” showed the removal of the shaft of the old waterwheel. Here we see that a platform has been built atop the old timbers that support the walls of the lock.

The old waterwheel was put into the lock after the canal went out of use so that water from the canal would turn grist stones to grind grain in the mill built adjacent to the lock.

$7 Million Matching Grant Awarded

Indiana’s General Assembly has awarded a $7 million matching grant from the state’s biennial budget to the Whitewater Canal Historic Site for renovation of its site in Metamora, Indiana. The $14.4 million project includes the renovation of the Laurel Feeder Dam, Locks 24 and 25, and Duck Creek Aqueduct; dredging the canal to remove built-up silt; and replacing the canal boat and dry dock station. It is now up to Whitewater Canal Museum and Historic Sites and the community around Franklin County to work together to fund their portion of the project. Saving this portion of the historic Whitewater Canal could be transformative to Metamora, Franklin County, and the state of Indiana. Hip, Hip, Hooray!