Index

Developing Indiana’s Transportation Routes

By: Bob Schmidt

The State of Indiana was originally occupied by native peoples. In 1679 Robert LaSalle entered this area via the south bend of the St Joseph River and traveled southwest down the Kankakee River. From that time until the end of the French & Indian War in 1763 this land was part of New France. The British gained control in 1763 when France ceded these lands via the Treaty of Paris. This ended the colonial and continental struggle.

King George III of England issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763 that forbade English settlers on the coast to settle beyond the Appalachian Mountains. This was largely ignored by the colonists since the original charter of the Jamestown Settlement in 1607 provided that the colony would extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific however far that might be. The land that would become Indiana was thus claimed by this colonial grant to be part of Virginia. Thus the 1763 proclamation became a contributing factor to the American Revolution.

Before the end of the American Revolution the colonies united under The Articles of Confederation. Maryland was the last colony to ratify these Articles. Her concern was that several states, primarily Virginia, claimed huge western territories that put Maryland and the smaller states at a future disadvantage. These contested claims were subsequently ceded to the federal government. The largest claim of Virginia was surrendered in 1784.

Under the Articles of Confederation, Congress dealt with Daniels Shay’s rebellion of soldiers in Massachusetts, but it is best known for establishing the land policies of the Northwest Territory. The Ordinance of 1784 described the territory and declared that states would be created and that slavery would be prohibited. The Ordinance of 1785 provided for the creation of land measurements with congressional townships of 6 miles square composed of 36 sections and each section was one mile square or 640 acres. Finally came the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which stated that this territory would be made into no less than 3 nor more than 5 states. This ordinance defined the government of the territory and the path to statehood. It established the capital at Marietta, Ohio.

It was one thing for the new nation to legislate these lands, but native people still occupied most of the territory and the British still occupied Detroit, supporting Indian depredation on American settlers moving into the Northwest Territory. In 1789 the United States was officially established with a new Constitution and its first president, George Washington.

President Washington immediately sent Revolutionary War General, Josiah Harmer, to the Northwest in 1790 to quell the Indian raids on settlers. Harmer’s army was defeated at the Miami village of Kekionga (Ft Wayne). Again a larger military force in 1791 led by Arthur St Clair, Revolutionary War General and 1st Governor of the Northwest Territory, was defeated near the headwaters of the Wabash River in Ohio. The British supported the Indians by building Ft. Miami on the Maumee River near today’s Toledo. Finally the Indian threat was disabled by General Anthony Wayne in northwest Ohio at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in August 1794. Wayne went on to seize the strategic portage at Kekionga and establish Fort Wayne.

In 1795 Wayne meet with a confederation of Indian tribes at Greenville, Ohio. Here they agreed on the Treaty of Greenville. In Ohio, lands south of Fort Recovery all the way to the Pennsylvania line were open for white settlement. Also a diagonal line from Fort Recovery to the mouth of the Kentucky River opened more land for white settlers. This separate line dissected about ½ of the Whitewater Valley and ran through Boundary Hill that lies just west of Brookville, Indiana. This allowed settlers from Fort Washington (Cincinnati) to safely move into the lower Whitewater Valley.

Indiana Territory was created in 1800, but “The Gore,” the diagonal 1795 treaty line, remained within the Northwest Territory that was to subsequently become Ohio in 1803. At the time of Ohio’s statehood “The Gore” was transferred to Indiana Territory to create a straight boundary, north to south, for the state of Ohio.

Commercially the Whitewater Valley was tied to Cincinnati, but the political capital of Indiana Territory was at Vincennes on the Wabash River, an unhappy situation for the Whitewater Valley settlers. Treaties by Governor William Henry Harrison in 1804 & 1805 opened most of the land along the Ohio River for settlement. In 1809 at Fort Wayne, Governor Harrison negotiated another 12 miles immediately west of “The Gore” for settlement that incorporated nearly all of the Whitewater Valley. The treaty line is marked by a stone on the west side of Cambridge City. In 1813 John Conner established Connersville. Then in 1816 Indiana achieved statehood. “The Gore” stayed with Indiana and the new state capital was more centrally located at Corydon along the Ohio River.

The natural commercial trading center for the Whitewater Valley was Cincinnati. Reaching that market meant traveling over very rough and muddy roads. Livestock was driven overland with resulting loss of weight thus profit. Settlers coming into the valley came by steamboat to Cincinnati. Steamboats traveled along the Ohio River beginning with the “New Orleans” in 1811. As early as 1823 delegates from neighboring counties meet at Harrison, Ohio to discuss the opportunities for a canal to connect the valley with the Ohio River.

President James Monroe, 1817–1825, felt that the U.S. Constitution did not support federal aid to state internal improvement projects. He vetoed the extension of the Cumberland (National) Road in 1822. In spite of this political negative environment, Congress, in response to a request from the Indiana Legislature, was able to pass a bill in 1824 providing a 90 foot right-of-way on either side of a proposed 25 mile canal along the Fort Wayne portage to the mouth of the Little River at Huntington. This did not provide for any financing beyond gifting the narrow strip of land. The bill required construction to begin in 3 years. Indiana rejected this meager federal support.

John Quincy Adams, in a contested election with Andrew Jackson, was selected by the House of Representatives in 1825 to become the 6th President of the United States. Adams was the first president to endorse wholeheartedly internal improvements without constitutional reservations. Andrew Jackson and his Democrat associates opposed these projects for federal assistance.

The Erie Canal in New York state, begun in 1817 and nearing completion by 1825,was entirely state funded. New York Governor Dewitt Clinton came to Ohio and conducted groundbreaking ceremonies at the Licking Summit of the Ohio and Erie Canal and also at Middletown, Ohio for the Miami Canal. With the support of President Adams the attitude for internal improvements had changed. In 1826 Congress authorized Colonel Shriver to lead a Corps of U.S. Engineers for canal surveys in the Whitewater and the Wabash valleys. The upper Wabash received most of the attention of Indiana Governor Ray and Senator John Tipton as the most likely route to receive federal support. Another consideration might have been that Senator Tipton owned considerable land along the route. Since much of the land was still in Indian hands, a treaty with the Indians was required. Governor Ray, John Tipton and Lewis Cass conducted the negotiations for the Treaty of Paradise Spring in Wabash, Indiana that was signed in the Fall of 1826.

The 19th Congress met from March 4, 1825 – March 4, 1827. The House was composed of Ant-Jackson men, but the Senate was slightly Jacksonian. The Congressional election of 1826 produced a House majority for Jacksonian Democrats. This put internal improvements in jeopardy so it was crucial that any hope for internal improvements rested with the 19th Congress before the next Congress was sworn in. With the land along the Wabash now secured, in the last days of the 19th Congress on March 2, 1827, a bill was passed for a land grant. This grant was specifically for a canal not a rail road. Alternate sections of land 5 miles on either side of the canal route from the mouth of the Auglaize River in Ohio to the mouth of the Tippecanoe River near Lafayette, Indiana were given to the state. This was a grant of 527,271 acres, the first of such type grant. It required commencement of construction within 5 years. Indiana legislative debate followed. Should the land grant be accepted for a canal or should Indiana build a rail line instead? Eventually the canal grant was accepted, land was surveyed, sales begun by 1830, and ground broken for canal construction on February 22, 1832, at the Fort Wayne summit. The Presidential election of 1828 brought a landside for Andrew Jackson vs. Henry Clay ending hopes for other internal improvements. In May 1830 Jackson vetoed the Maysville Road bill for constructing a road from Maysville to Lexington Kentucky.

There was considerable discontent in the Whitewater Valley as canal planning and construction was going on all around them. The 1830 Federal Census found over 52,000 persons in the valley while there was only about 10,000 people from Fort Wayne to Lafayette. Even though Allen County had a population of only 1000, a canal was being built through it.

The original engineering survey in the Whitewater Valley showed a elevation fall from Hagerstown to Lawrenceburg of 491 feet in a valley too narrow to support a canal. Ohio had built the Miami Canal from Dayton to Cincinnati from 1825-1828. Again in 1832 citizens in Connersville demanded another survey of their valley. In 1834 Jesse Williams lead a team to review the possibilities of a White Water Canal. This 2nd look, completed in December 1834, stated that a canal was possible but required 7 feeder dams and 56 locks at an estimated cost of $1.1 million.

The National Road construction reached Indiana by 1827. The road was routed to pass through three State Capitals: Columbus, Ohio: Indianapolis, Indiana; and Vandalia, Illinois. By 1835 the maintenance of this roadway was turned over to the states as Jackson and the Democrats were not interested in a federal role in internal improvements. Jackson’s idea was to take the federal surplus and return funds to the state for their projects. The National Road passed through Richmond and Cambridge City making the need for a connecting canal all the more necessary. The capital for Indiana was moved from Corydon to Indianapolis in 1825. With the state capital now in the center of the state, pressure mounted for a canal route there as well. The population of Marion County in 1830 was only 7,200.

By 1835 the Wabash & Erie Canal was completed to Huntington and work was proceeding toward Wabash, Indiana. Governor Noah Noble, a Brookville politician, supported a Mammoth Improvement Bill for the state, which he signed in January 27, 1836. It provided for canals, roads and river improvements and at last $1.4 million for a Whitewater Canal. To complete this canal required that from the Harrison Dam the route would turn into Ohio for 7 miles before returning to Indiana and proceeding to Lawrenceburg. In the land negotiations with the state of Ohio, Indiana agree to allow private Cincinnati investors to build a Cincinnati and Whitewater Canal and merge at the Harrison dam. This was certainly agreeable with valley citizens as they most likely wanted to trade in Cincinnati vs. Lawrenceburg anyhow. The 1836 Improvement Bill also provided for a Central Canal, an extension of the Wabash & Erie Canal to Terre Haute, a Madison to Lafayette railroad, some Wabash river improvements and some additional canal surveys. This was probably the most comprehensive plan of any of the states.

The Whitewater Canal was begun with groundbreaking at Brookville, Indiana on September 13, 1836. Feeder dams No. 1-3 and locks No. 1-17 were completed by June of 1839. The Ben Franklin was the first canal boat to travel between Brookville and Lawrenceburg.

In 1839 Indiana was unable to pay the interest on the $10 million bonds borrowed at 5%. Work on improvements throughout the state stopped except for the Wabash & Erie Canal, which was funded by the sale of federal land previously granted.

For three years nothing happened on the Whitewater Canal beyond Brookville. The planning of the Cincinnati & Whitewater Canal was completed by Darius Lapham in 1837. His survey suggested that the commercial traffic from the Whitewater would be 50% greater than the Miami Canal from Dayton. His survey also stated that either a deep cut or tunnel would be required to pass through the farm of William Henry Harrison at Cleves, Ohio. Harrison was a subscriber to the stock of the private company building the canal. Groundbreaking took place on March 31, 1838 on the Harrison farm for the Cincinnati & Whitewater Canal. The decision was made to build a tunnel with bricks made on the Harrison farm. The tunnel was 1700 feet long and was completed about 1841. The Cincinnati & Whitewater Canal reached the Harrison dam in November 1843. Earlier in May 1843 the Wabash & Erie was opened from Lafayette to Toledo.

In 1841 Indiana sold the Whitewater Canal to Henry S. Valette, a Cincinnati businessman. It was incorporated as the White Water Valley Canal Company. The Canal House in Connersville became the company’s headquarters and work was resumed on the old state works beyond Brookville. On July 28, 1842, over 10,000 people gathered at Cambridge City for a grand barbecue celebration. By October 1843 the canal reached Laurel. It was completed to Connersville by June 1845 and to Cambridge City by October of that year. Now 68 miles was opened to Lawrenceburg and 83 miles to Cincinnati.

Although the original survey for the Whitewater Canal back in 1830s began at Hagerstown, the newly created White Water Valley Canal Company was chartered to only reach Cambridge City. The merchants of Hagerstown were charted separately by the legislature to form their own company in 1843. This company hired engineer John Minesinger, who had worked with Jesse Williams on the earlier valley survey. He laid out this portion of the canal staying away from the Whitewater River so that the Hagerstown Canal was never impacted by flooding. The works consisted of 1 Feeder Dam on the Whitewater River, 1 stone culvert, 1 aqueduct over Symonds Creek, and 6 composite locks. Work began on this 8-mile-long canal in the summer of 1846 and was completed by the Fall of 1847. This was a remarkable accomplishment for such a short period of time.

The Whitewater Canal was unlucky when a great flood occurred in the late Fall of 1847. Repairs were made in 1848 along the upper portions of the canal, but the canal from Harrison to Lawrenceburg never reopened. Of course the major market to Cincinnati was still open with the Cincinnati & Whitewater Canal portion opening in 1843. The whole Whitewater canal system became unprofitable and was sold to railroad interests in 1862.

Conclusions: With the large concentration of population in the Whitewater Valley and the sparse population along the Wabash River, why did the Whitewater develop so much later? Geography and glaciations had tipped the scales to the northern route. The Fort Wayne summit is the lowest elevation between the Maumee and Wabash valleys. As Governor Ray had suggested this site was of strategic national importance to move goods and troops from the Mississippi Valley to the northeast. As a result federal aid in the form of a land grant was made available to the state of Indiana. Likewise the earlier glacial outpour had created steep valleys for the two branches of the Whitewater River. The original surveys predicted that a canal might fail due to flooding and the need to build the canal close to the river in a narrow valley. The Whitewater drops 6.4 feet per mile vs. the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal’s 2.9, Erie Canal’s 1.7and Wabash & Erie’s 1.0 foot per mile. The Whitewater valley runs north to south and had little strategic military value. Larger cities developed on the upper Wabash as rail lines running east to west followed the canal route. Rail traffic in the Whitewater never really developed and today towns still remain quite small with the exception of Connersville and Richmond.

Gideon Jenks (Jinks) & Jinks’ Lock

By Carolyn I. Schmidt

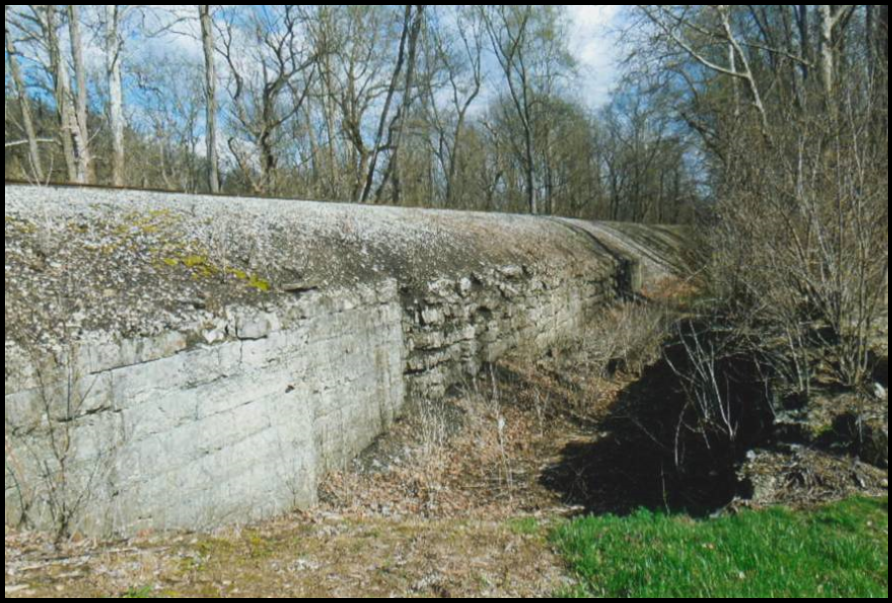

A question arose during the Canal Society of Indiana’s spring tour “Whitewater Canal Locks” on May 4, 2019 as to how Jinks Lock had been named. We knew it was Number 29 of all the 56 stone locks on the canal and was a composite lock with finished cut stone abutments and a plank lined, rubble stone chamber. We assumed the lock was named for the locktender but needed research to confirm it.

A question arose during the Canal Society of Indiana’s spring tour “Whitewater Canal Locks” on May 4, 2019 as to how Jinks Lock had been named. We knew it was Number 29 of all the 56 stone locks on the canal and was a composite lock with finished cut stone abutments and a plank lined, rubble stone chamber. We assumed the lock was named for the locktender but needed research to confirm it.

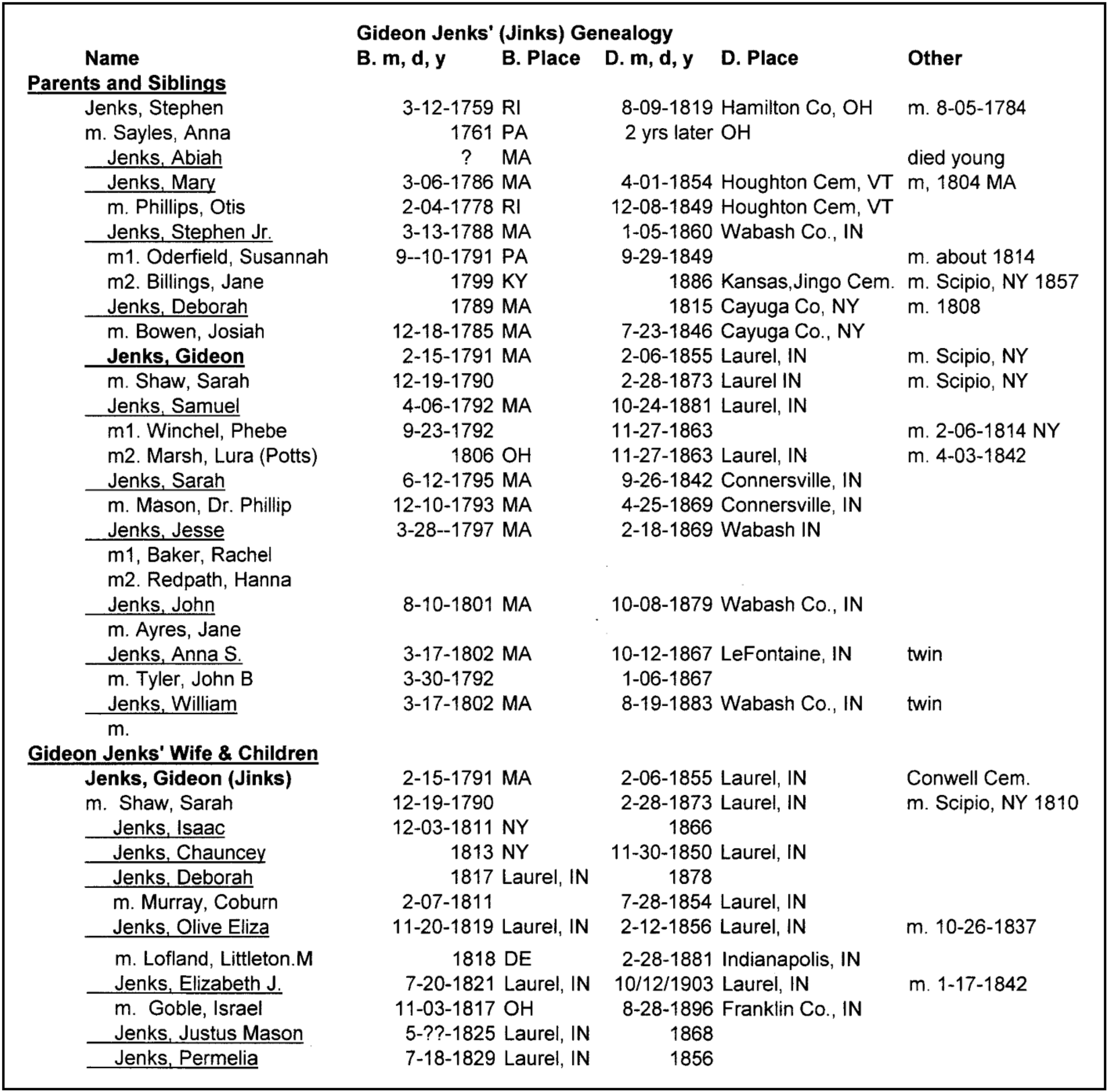

Luckily Dr. Philip Mason, whose first wife was Sarah Jenks, wrote a book entitled “A Legacy to My Children, Including Family History, Autobiography, and Original Essays” in which he included a great amount of the Jenks’ family history. In it he gives the following history:

Joseph Jenks (1599-1683) “came from Hammersham or Hounslow, near London, England, to America, in 1643. He was a worker in iron; and, in 1646, obtained a patent from the General Court of Massachusetts for making scythes and mills, which was among the earliest taken out. He was a widower, and had left a son in England to be educated…. He went with his young family into Rhode Island. Joseph had a son Joseph, who also had a son Joseph, who was Governor of Rhode Island from 1727 to 1732.”

“The Jenks families were remarkable for longevity, and were very prolific. Jesse Jenks along with his brothers, Edmund, Isaac, and Lawrence, emigrated from Demerara, in British Guiana, South American, to North America, prior to the American Revolution, and settled, first, in the Province of Rhode Island. They all married and finally settled in Berkshire County, Massachusetts.

“Jesse Jenks married Rhoda Smith. The date of this marriage is unknown. They settled in Cheshire, Berkshire county, Massachusettes and had seven children, After Rhoda died, he married Abigail Sayles and had six more children. He lived to be ninety years of age and died on a large farm in Cheshire, where he had first settled.

His son Jesse married and had six children, one of which was also named Jesse. This third Jesse Jenks had a son named Stephen Jenks, who married Anna Sayles. Stephen and Anna had eleven children, six boys and five girls: Abiah, Mary, Stephen Jr., Deborah, Gideon, Samuel, Sarah, Jesse, John, Anna and William. “These children were all born in Adams, Berkshire county, Massachusetts. While his youngest children were small, he moved from Adams to Scipio, Cayuga county, New York, where he owned a fine farm, on which he lived; was comfortably situated and lived in easy circumstances. He and one of his sons took a trip West, through Kentucky into Tennessee, and into Indiana, and on the White River, and also over a considerable portion of Ohio, and returned home.

“In the spring of 1814, his three oldest sons, Stephen [Jr.], Gideon, and Samuel, left home, in wagons, for Indiana, traveling the entire distance by land. They bought land and settled, in common, a mile below where Laurel now is located, on White Water, Franklin county, Indiana, then a Territory.

“In the spring of 1816, Philip Mason, who had married Sarah Jenks, one of Stephen Jenks’ daughters, left Scipio, New York, in a wagon, and on arriving at Olean Point, took passage on a raft, and landed at Cincinnati, Ohio, on the 15th of April, 1816, and went out to White Water, to the residence of his wife’s brothers. In June, the remainder of the family left Scipio, and reached the sons’ [homes] in July, having traveled the whole distance by land. (That season was known as the cold summer, it being so cold that but little corn was raised in the State of New York that year. On White Water, the morning of the 7th of June was frosty, and uncomfortable cold in planting corn, and in Cayuga county, New York, it snowed that morning.)

“Their arrival, and the meeting of the whole family [except Stephen’s daughter Mary, who was married and lived in Vermont] was a pleasure, which must be enjoyed to be appreciated. After a few days of hilarity and pleasure spent in talking over old times and family relations, and of the future permanent settlement, it was determined upon that a trip across the State [Indiana] to the Wabash [river] should be made. An outfit was arranged, and Stephen Jenks, Sr., his son Samuel, Philip and Horatio Mason, and a Mr. Bush, left and took a trace from Brookville, through the woods, into what was an Indian country, to Brownstown, in Jackson county; then to Vincennes; then up the Wabash to Fort Harrison, above where Terre Haute is now situated. On their] return, [they] struck through the woods from Busroe Creek to Bean Blossom; then home by Brownstown and the outward route. [They] were absent twenty-one days, and not pleased with the country. [Stephen, Anna and the majority of their family] settled on a large farm of excellent land lying on both sides of the Big Miami River, at Colerain, [Ohio] a short distance below where Venice now is situated. Here, the family suffered much from sickness, and several died. Stephen died first, and two years afterwards Anna, his wife died. [Also their son Jesse lost his wife and their child Samuel.]

“Here we have a specimen of the folly of old people changing their location for one differing materially in clime and local influences. After the deaths here mentioned, the remainder of the family left the place, and the farm passed into the hands of strangers.”

Through his mother Anna Sayles Jenks, Gideon Jinks is a descendant of Roger Williams (1603-1683), who founded Rhode Island. On his father’s side he is descended from Joseph Jenks the scythe inventor as before mentioned. Although Gideon is a descendant of this Jenks family, he and several of his children preferred to spell Jenks as Jinks.

Feb. 115, 1791-Feb. 6, 1855

Conwell Cemetery, Laurel,

Franklin county, Indiana

In 1810 Gideon Jinks married Sarah Shaw in Scipio, Cayuga county, New York. They emigrated with Stephen [Jr.] and Samuel Jenks, purchased land in common, and settled a mile beneath Laurel, Indiana as before stated. Then on May 1, 1833 Gideon Jinks purchased land in the E½SW½ of section 21, township 12N, range 12E at the 2nd prime meridian in Franklin, Indiana. The three brothers resided on their common land until about 1838, when they dissolved their partnership. Stephen [Jr.] sold his interest to Gideon, and then moved with his entire family into the northeast corner of Wabash county, Indiana. Thus Gideon had title to two adjacent farms. He lived and died on the farm adjoining the one on which they first settled.

The Whitewater Canal was opened to Laurel, Indiana in 1843. A dam was built across the Whitewater River below Laurel to feed the canal. Jenks Lock was built on the east side of the river almost across from the dam. It was in the SE¼ of section 16, Laurel township and was a composite lock with cut stone abutments and a plank lined rubble stone chamber. It was on land that the three Jenks brothers had settled and was owned by Gideon Jinks at the time the canal was built. Therefore, it was named for Gideon Jinks. Perhaps he or his children tended this lock.

Dec. 19, 1790-Feb. 28, 1873

Conwell Cemetery, Laurel,

Franklin county, Indiana

Over his lifetime Gideon Jinks acquired a handsome estate. Upon his death on February 6, 1855 at age 63, he was laid to rest in the Conwell Cemetery in Laurel, Indiana.

His wife Sarah died on February 28, 1873. Her obituary was found in the Franklin Democrat of March 6, 1873:

“Mrs. Sarah Jenks, aged 83 years, died at the residence of her son-in-law, Hon. Israel Goble, near Andersonville, Feb. 28th, 1873. Her remains were brought to the Laurel cemetery March the 1st, and deposited in the grave along the side of her late husband, Gideon Jenks, two daughters and one son, who had proceeded her to the spirit world. Mrs. Jenks emigrated with the husband from Cayuga county, New York, to Indiana in the spring of 1814 moving all the way through in wagons, and settled along with the families of Stephen [Jr.] and Samuel Jenks who emigrated from the same place at the same time on a large body of fine lands two miles south of the present site of Laurel, where she lived over fifty years, honored and respected by all her neighbors. The last few years she has been living with her surviving children, Mrs. Deborah Murray and Mrs. Elizabeth Goble. A few weeks before her demise she was attacked with influenza which was followed by increasing debility, resulting in her dissolution. She was a firm Universalist.”

There is also a Jenks Cemetery located on Dam Road near Laurel, Indiana. Photos have been taken of about 18% of those buried there.

There is also a Jenks Cemetery located on Dam Road near Laurel, Indiana. Photos have been taken of about 18% of those buried there.

Sources:

Ancestry:

U.S. General Land Office Records, 1776-2015

Public member trees: Found many errors in dates

Find-A-Grave: Gideon, Sarah, siblings & children

Franklin Democrat, March 6, 1873

Indiana Marriages 1810-2001

Mason, Dr. Philip. A Legacy to My Children, Including Family History, Autobiography, and Original Essays.

Cincinnati, Ohio: Moore, Wilstach & Baldwin, Printers, 1868.

Ohio Wills & Probate Records 1786-1998

U.S. Federal Census: 1820,1830,1840,1850

“Whitewater Canal Locks” Tour

Photos by Carul Bauer unless otherwise noted

At 9 a.m. on May 4, 2019 twenty-seven “Whitewater Canal Locks” tour attendees gathered at the old Whitewater Canal headquarters building in Connersville, Indiana to begin the weekend’s events. Dressed for cold, rainy weather they were in high spirits.

Fayette County historian Donna Schroeder guided the group through the building, pointing out the two old safes that once stored canal documents and money. After the canal era the building had several uses before being purchased by Finly and Alice Gray, who used it as their home.

Mr. Gray was a U.S. congressman. Historic Connersville now owns the building and has furnished it as the Gray residence. Donna also pointed out that a kitchen wing had been added to the original building.

They are in the process of restoring the second floor, which had been used as a meeting room. Therefore, the Canal Society’s annual meeting was moved to the new Fayette County Historical Museum located two blocks away.

Across the street from the Canal House was the Connersville Mystery Mural, where an old photo had been enhanced, colorized, and divided into forty five squares. Each artist was given a square to enlarge to a two foot square panel. They hadn’t seen the entire picture until the panels were assembled into the mural.

We moved our cars and walked to the Fayette Museum for our meeting in the conference room. Sue Simerman, nomination’s chairman presented a slate for the CSI Board of Directors. One third of the 18 directors are elected/re-elected every year. This year Tom Castaldi, Don Haack, Jeff Koehler, Sam Ligget, Mike Morthorst, and Bob Schmidt were up for re-election. Due of health issues Don Haack asked to be replaced. Sue then nominated Stan Schmitt to fill Don’s seat. The slate was unanimously approved.

New CSI Director – Stanley “Stan” Schmitt

Stan Schmitt of Evansville, Indiana has a degree in history from Indiana University. He has been a member of the Canal Society of Indiana for many years and has served the organization as follows:

Stan Schmitt of Evansville, Indiana has a degree in history from Indiana University. He has been a member of the Canal Society of Indiana for many years and has served the organization as follows:

- Former CSI board member 1984-1995

- Former Editor of CSI’s “Indiana Waterways” and “Indiana Canals” 1989-1998

- Long time Indiana canal researcher and tour planner

- Vanderburgh County Historian

- Historical speaker who appears in local PBS documentaries, local TV and newspapers

- Frequent writer for Evansville Living’s “Encyclopedia Evansville”

Following the election of directors, Sue presented the slate of officers, who were all re-elected:

Bob Schmidt, president; Mike Morthorst, vice-president; Sue Simerman, secretary; Cynthia Powers, treasurer; and Carolyn Schmidt, “The Tumble” coordinator

Jerry and Phyllis Mattheis passed out literature about Connersville, the Whitewater Canal Byway, etc. Following the short business meeting, Bob Schmidt gave a talk about the Whitewater Canal, when, where, and why it was built, and what would be seen that afternoon from the train.

Tour attendees looked at the museum’s exhibits. The antique cars that were built in Connersville and the Whitewater Canal room attracted most of the attention.

Following the tour of the museum, attendees ate a lunch of pulled pork sandwiches, coleslaw, baked beans, chips, and drinks in the conference room. It was catered by Rip’s Family BBQ.

Each attendee was given a ticket for the afternoon train ride on the Whitewater Valley Railroad from Connersville to Metamora and back. They also were given a pencil and a booklet listing the 17 locks of the Whitewater Canal, their location, section, city/township, directions, and type/lift of each, that would be passed by the train. They were asked to jot down the condition of the locks, if signage pointed out their location, and if the attendee thought there was any chance of restoring and re-watering the canal. Ready for an afternoon of adventure, they walked to the train depot.

Photos B. Schmidt, C. Bauer, S. Simerman

Photos by Carl Bauer taken from the train

Attendees found that of the 17 locks listed only 9 were actually seen, had signage along the railroad, and were in various stages of deterioration. There was signage at the Laurel Feeder Dam, and 3 signs marking locks along the road. The docent aboard the train said that one of the best locks could not be seen from the train. This was Murray’s Lock 26. With all the water from the heavy rains, we saw two really good areas that could be cleared in dry weather and impounded during the rest of the year to show the canal prism. One of these was a section from Nulltown to the airport and another north and south of Bide-awee, an old campground. It was suggested that a sign be placed at the wooden aqueduct over the West Fork of the Whitewater River, which rests on original caissons, and that Conwell’s Lock 40 and Herron’s Lock 38 also be marked. Also suggested was that trees that are compromising lock ruins be removed and two houses located near locks be investigated for historical importance.

John Hillman, President of the Whitewater Valley Railroad and CSI Director, accompanied us on the train and talked about the 200 volunteers that work on the railroad. Our docent on the train was very informative about the canal and the railroad. He, his wife, and both children volunteer several weekends a month in various capacities.

The train reached Metamora, and stopped at Lock 25 and the Grist Mill, which once used canal water to turn its grindstones.

Lock 25 was on the opposite side of where everyone got off the train. After walking around the engine, the restored cut stone lock and water flowing over the tumble was easily seen. After the canal era an overshot wheel was placed in the lock chamber to power the grist mill. It is no longer used to turn the mill stones.

Attendees then chose between a walking tour of Metamora led by Mike Morthorst or taking a ride on the “Ben Franklin III,” a canal boat replica operated by Indiana State Historic Sites.

Photos by Sue Simerman and Carl Bauer

The docent aboard the boat talked about the Whitewater Canal and Duck Creek Aqueduct as we glided down the canal pulled by horses. Passing through the covered bridge aqueduct, noting how it was built and how the horses had to be unhitched to walk around it while the boat floated through and then re-hitched, and noting the speed of the boat was relaxing and informative.

From the canal boat attendees proceeded to the grist mill. There a docent talked about how the grain was ground and the types of grind stones used. The three story mill was built by Jonathan Banes, a former contractor on the canal, in 1845 and converted it into a grist mill in 1856. After it burned down it was rebuilt in 1900. After another fire it was rebuilt in 1932 as a two-story brick building.

Attendees had a little time left to explore the shops in Metamora before boarding the train to head back to Connersville. Once back they drove their cars to the home of Governor Oliver P. Morton in Centerville for an 1850s dinner with Governor Morton.

Dr. Ron Morris, History Professor at Ball State University, who owns the home where Gov./Sen. Oliver P. Morton once lived in Centerville, Indiana, hosted the event. The house was built in 1848 by Jacob Julian and purchased by Morton in 1857. He owned it until 1863.

Cloth covered tables were set up in several rooms for dining and buffet tables were set up in the actual dining room. A delicious 1850s style dinner of chicken and vermicelli soup, wilted greens, pickled spiced pea pods, minted carrots, assorted breads and jams, glazed ham, creamed peas, sweet potato casserole, crisp asparagus spears, a mixed berry trifle and iced tea was catered by Radford’s Meat Market and Deli. Plates were filled to overflowing. As the sun faded coal oil lamps illuminated the rooms and attendees moved their chairs to the dining room.

The program for the evening was a first person presentation of Oliver P. Morton by Kevin Stonerock. Oliver P. Morton was Indiana’s Governor (1861-1867) and Senator (1867-1877). He limped into the room since Morton had had a stroke, sat down and told his life story in a humorous and yet dignified way. He reminded everyone that Morton had wanted to be remembered as a “friend of the soldier.” Kevin then came out of character and answered questions from the audience thus ending the enchanting evening.

At 9 a.m. on Sunday the attendees gathered in front of the James Raridan home, also owned and restored by Dr. Ron Morris, to begin a walking tour of historic Centerville, Indiana. Ron pointed out the unique architecture of the row houses that had arches between them leading to courtyards. Some of the arches have been destroyed. He told how the town changed from its north-south orientation to an east-west orientation with the coming of the National Road, old U.S. 40. He pointed out the building Morton once working in as a hatter with his brother William, where Morton went to live with his two aunts in 1837, and a place where a canon ball hit the courthouse (now library) during a struggle to move the county seat from Centerville to Richmond in 1870.

Photos by C. Bauer and B. Schmidt

The next stop was at Riverside Cemetery in Cambridge City where Phyllis Mattheis talked about General Solomon Meredith (5-29-1810 to 10-2-1875), a prominent Indiana farmer, politician, and lawman, who was a controversial Union Army general in the Civil War. He gained fame as one of the commanders of the Iron Brigade of the Army of the Potomac, leading the brigade in the Battle of Gettysburg where he was wounded. This monument once stood on his nearby farm. She also pointed out the graves of:

Elbridge Gerry Vinton, the proprietor of the Vinton House, a thirty-four room hotel established in 1847 in Cambridge City that was adjacent to the Whitewater Canal, which brought passengers and freight from Cincinnati and the National Road.

Valentine and Sarah Sell, a canal boat captain and cook who were friends of the Vintons.

Overpeck family, whose daughters were famous for their “Overbeck”pottery and art work, taught music and art, and fired their pottery in a kiln beside their home.

Photos by C. Bauer, B. Schmidt, and S. Simerman

Then the group met Mr. and Mrs. Troy Lewis, the latest owners of the Solomon Meredith home. They pointed out where Meredith’s statue was once located in a family burial plot, told the history of the Meredith home and how its front was on Meredith street, a north-south street, that is now a dead end, and said that the building has had at least three additions. They are in the process of restoring it.

They also talked about Virginia Claypool Meredith, Solomon’s daughter-in-law, who lived on and managed the farm. She was an American farmer and livestock breeder, a writer and lecturer on various topics of agriculture. A dormitory at Purdue University is named for her.

In Cambridge City, a stone with a plaque read: Indian Boundary Line— Marking the twelve mile purchase from the Indians by the Fort Wayne Treaty of 1809 by Governor William Henry Harrison. A few blocks away was a mural honoring Solomon Meredith. It was across the parking lot from No. 9, a restaurant where some of the canawlers had lunch. This ended another successful tour.

“Whitewater Canal Locks” Tour

- Tour planners: Dr. Ron Morris, Bob & Carolyn Schmidt

- Tour guide book, check list of locks, goodie bags: Carolyn Schmidt

- Motels: Red Roof Inn, Comfort Inn Richmond, IN

- Dinner at Morton house and speaker: Dr. Ron Morris

- Registration/Confirmation: Carolyn Schmidt

- Budget and arranging for motels, train & canal boat trips: Bob Schmidt

We wish to thank the following in the order they hosted us:

- Whitewater Canal Headquarters—Donna Schroeder, Fayette County Historian

- Fayette County Historical Society Museum—Brad Colter and crew

- Lunch from Rip’s Family BBQ—Tom Ripberger Jr.

- Whitewater Valley Railroad—John Hillman, President Whitewater Valley Railroad, train crew, and an excellent docent

- Whitewater Canal State Historic Site—Jay Dishman, Ben Franklin III canal boat crew, great docents on boat and at the grist mill

- Walking tour of Metamora—Mike Morthorst

- Governor Oliver P. Morton home host—Dr. Ron Morris

- 1850’s Dinner—Radford’s Meat Market & Deli, Richmond

- Governor Oliver P. Morton first person—Kevin Stonerock

- Walking tour of Centerville’s architecture—Dr. Ron Morris

- Graves of Solomon Meredith, Valentine & Sally Sell, Gerry Vinton, Overbeck sisters in Riverside Cemetery, Cambridge City—Phyllis Mattheis

- Information and booklets on Whitewater Valley Scenic Byways, etc—Jerry Mattheis

- Solomon Meredith home—Mr. & Mrs. Troy Lewis

Saturday’s tour and dinner attendees: 27 (California 2, Indiana 23, Ohio 2)

Carl & Barbara Bauer, Leon & Sandy Billing, Tom & Linda Castaldi, Gary & Cassandra Ferris, Lowell & Jerry Goar, Tom Goughnour, Webster Hall, Bill Helbing, Phyllis Hess, Sue Jesse, Sam & Jo Ligget, Ron Morris, Mike Morthorst, Bob & Carolyn Schmidt, Steve & Sue Simerman, Neil & Diana Sowards, Frank & Mary Timmers

Saturday’s dinner only: 7 (Indiana 7)

John & Candy Carr, Susan Gooch, Margo Finney, Warren & Judy Smith, Linda Winchell

Sunday’s tour attendees: 22 (California 2, Indiana 18, Ohio 2)

Carl & Barbara Bauer, Leon & Sandy Billing, Margo Finney, Lowell & Jerry Goar, Tom Goughnour, Susan Gooch, Phyllis Hess, Sue Jesse, Jerry & Phyllis Mattheis, Ron Morris, Mike Morthorst, Bob & Carolyn Schmidt, Steve & Sue Simerman, Neil & Diana Sowards, Linda Winchell

Grant’s Canal Vicksburg, Mississippi

By Sue Simerman

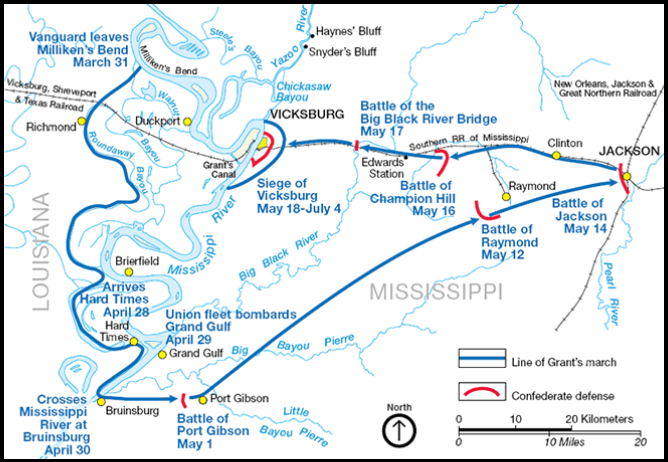

Major General Ulysses S. Grant was put in charge of the western campaign of the Civil War. He was to gain control of the Mississippi River and the regions from Cairo, Illinois to the mouth of the Mississippi below New Orleans. After his Army of The Tennessee conquered Memphis, Tennessee they were ready to continue moving south on the Mississippi to interrupt the supply lines for the Confederacy.

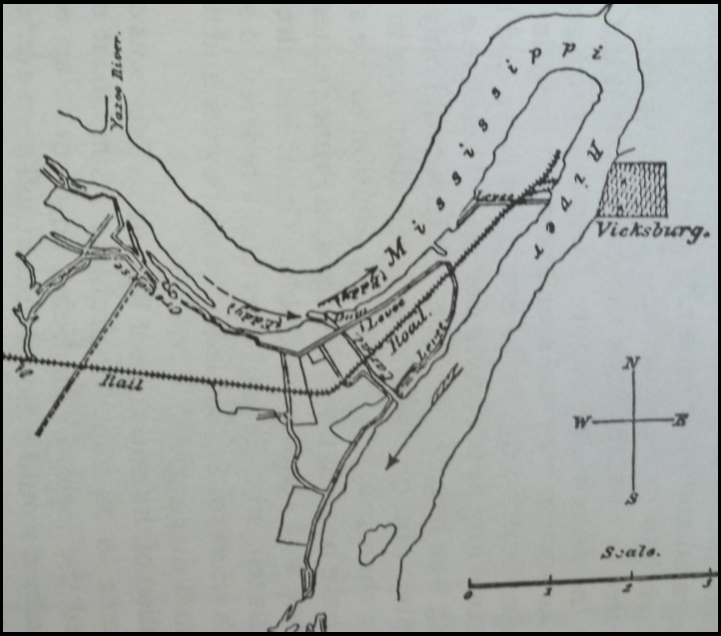

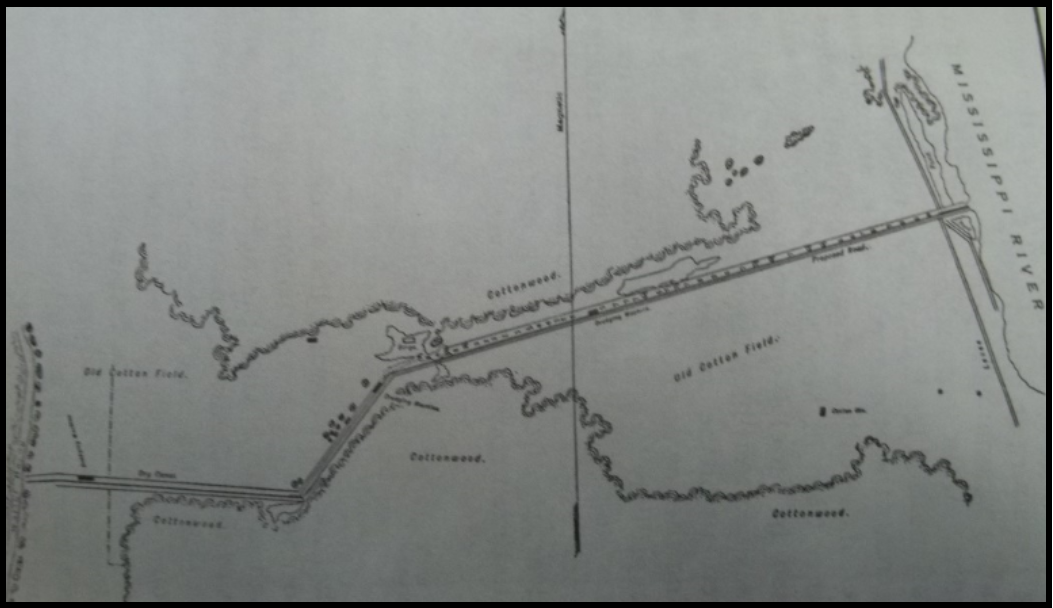

Next was Vicksburg, Mississippi. Taking this would be a major accomplishment. The town was situated on 200-foot-high bluffs above the river and the Confederate batteries located there had a very nice three mile lookout down upon the Mississippi River. This river had many bends and oxbows and at Vicksburg there was the long DeSoto Peninsula. It had a horse shoe bend on the north end near the town that is on the east side of the river. The natural river channel forming the peninsula was 10 miles long and the neck was three-fourths of a mile wide.

In April 1862 the Confederacy realized that Vicksburg needed to be defended. With two forts below New Orleans there was little worry of a Union attack coming up river from the Gulf of Mexico. An attack was expected to come from the north down the river.

Flag Officer David Farragut and his blockade squadron made it up to New Orleans from the gulf and the city fell. Farragut made it to just south of Vicksburg, May 18, 1862. This was the first fortified city they encountered. A request for surrender was made and refused. They soon learned that a battle from the water against the fortifications was not going to work. With some caution of studying the defenses, Farragut and fleet went back to New Orleans. The union commander of New Orleans, Major General Benjamin Butler, met with Farragut to discuss the capture of Vicksburg.

Their plan was for Farragut to return to Vicksburg by going upstream and having Commodore David Porter come along to fire mortars into Vicksburg. Troops would be needed also under Brig. General Thomas Williams. The plan was sent to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, it included the digging of a canal cut-off that would go straight across the neck of the peninsula across from Vicksburg. Stanton approved this project and passed it along to others in the naval forces.

Williams’ troops set up camp June 25 below Vicksburg. Colonel Ellet’s ram fleet came from the north as well as Commodore Charles N. Davis’s gunboats.

Surveying and excavating, removal of trees and brush began for this canal that would be one and a third miles long. The slope of this canal would naturally direct the river through it and change the route of the great Mississippi River.

On June 27, Farragut and Porter’s initial plan was put in place and Union firing took place from the river and from the Confederate military in Vicksburg. With the death of some Union men there still wasn’t a victory. More labor gangs were brought from the plantations to dig the canal as it became more and more important for the Union to have total control of the river, along with the railroads, supply lines and the road to the Mississippi capitol of Jackson. The work on the canal was a true hardship on the workers in the middle of summer, temperatures topped in the 90’s. Rations and drinking water were far from adequate. Add the pesky mosquitoes, Malaria and other diseases to the list of misery.

The canal was dug.

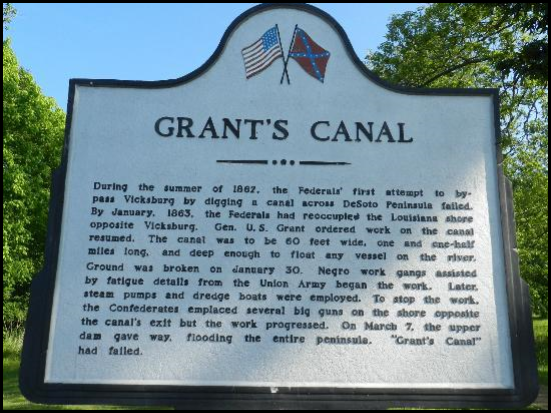

During the summer of 1862, the Federals’ first attempt to bypass Vicksburg by digging a canal across DeSoto Peninsula failed. By January, 1863, the Federals had reoccupied the Louisiana shore opposite Vicksburg. Gen. U. S. Grant ordered work on the canal resumed. The canal was to be 60 feet wide, one and one-half miles long, and deep enough to float any vessel on the river. Ground was broken on January 30. Negro work gangs assisted by fatigue details from the Union Army began the work. Later, steam pumps and dredge boats were employed. To stop the work, the Confederates emplaced several big guns on the shore opposite the canal’s exit but the work progressed. On March 7, the upper dam gave way, flooding the entire peninsula. “Grant’s Canal” had failed.

The river was low and continued dropping in July. The commanders were worried that the water levels would become so low that the fleets would be stranded in place. The canal came at a level above the low river. More digging is done. It was 15 feet wide and three to three and a half feet deep. It had been believed that when the embankment was removed that the rushing water of the Mississippi would help scour out more of a depth and width. The river had fallen 25 feet since May. The sides of the canal began to cave in. Many wished to dig deeper, but the heat and illnesses caused a shortage of laborers. The vessels became hospitals and graves had to be dug.

The Union Naval and Army forces were ordered to withdraw and left on July 24. It was believed that 600 graves marked the peninsula.

Meanwhile Vicksburg prepared for another attempt. New batteries and ammunition were stockpiled.

In October General Grant headquartered at Memphis. The Confederates led by Lt. Colonel John Pemberton regrouped at Vicksburg.

Major General Wm. T. Sherman had 60 transports and 32,000 troops and Porter and his fleet to approach Vicksburg. They had learned that a direct assault would not work. Sherman sends his fleet up the Yazoo River above Vicksburg. The Battle of Chickasaw Bayou took place December 27-29. The Union forces had to withdraw.

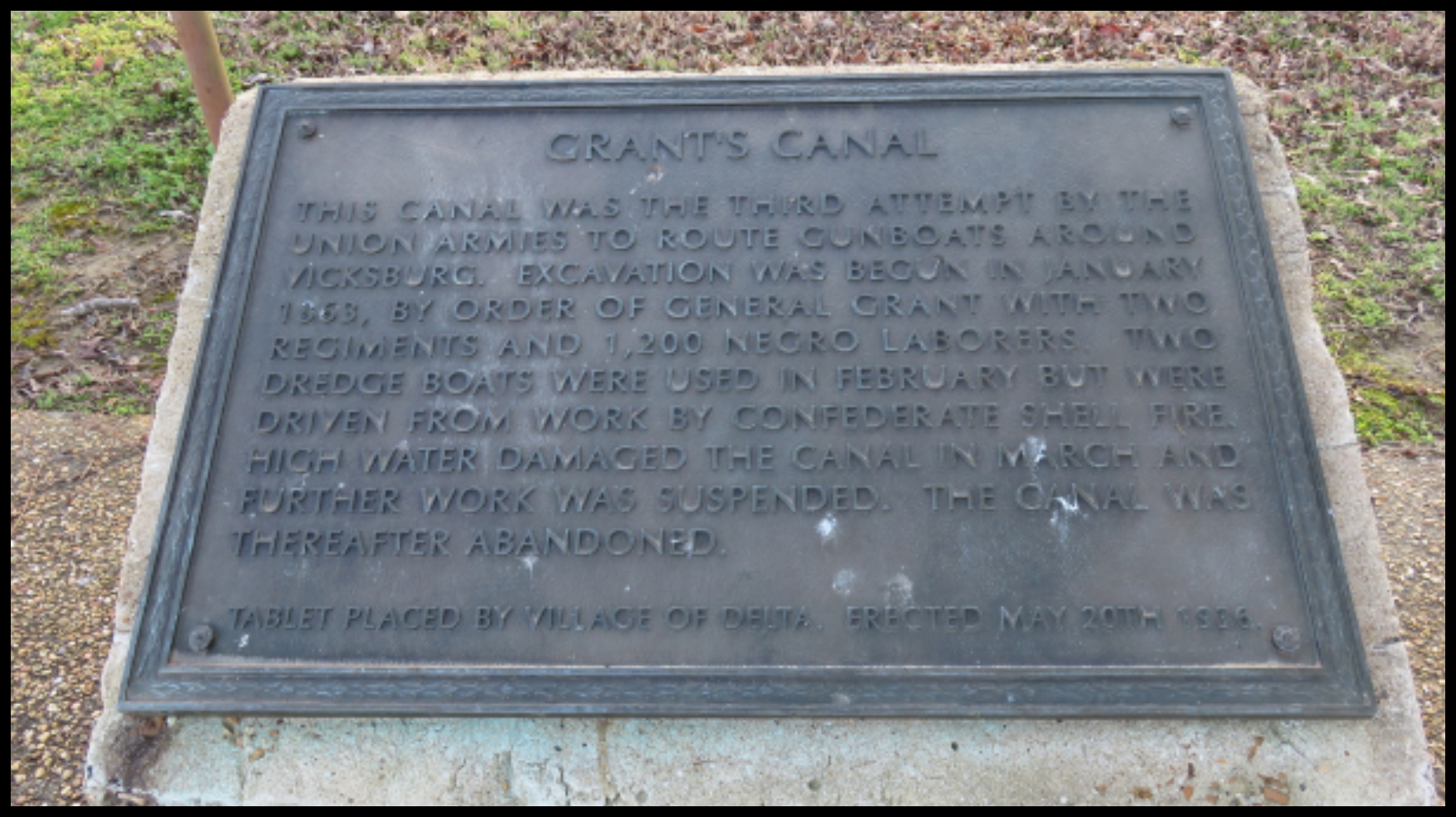

This canal was the third attempt by the Union armies to route gunboats around Vicksburg. Excavation was begun in January 1863, by order of General Grant with two regiments and 1,200 negro laborers. Two dredge boats were used in February but were driven from work by Confederate shell fire. High water damaged the canal in March and further work was suspended. The canal was thereafter abandoned.

Tablet placed by Village of Delta. Erected May 20th, 1936.

The canal that was never used was then called the Williams Canal. It was later known as Grant’s Canal.

General Grant needed to find a way to get his troops to attack by land. He ruled out the Yazoo River due to defense maneuvers, which included the enemy mining the river. He had three choices of getting below Vicksburg.

- Marching through Louisiana to the south and to the Mississippi River then transporting by ship to the other bank.

- Ferrying troops and supplies through the Louisiana bayous to the Red River and up the Mississippi.

- Returning to work on the Williams’ Cut-off Canal

The Second Attempt to Finish Grant’s Canal

In January of 1863 Grant ordered Col. Josiah W. Bissell to survey the Williams’ Canal. It was partly due to the influence of President Lincoln. The canal was to be 9 to 12 feet wide and a little more than 6 feet deep. There were stumps and trees to be removed on the slopes.

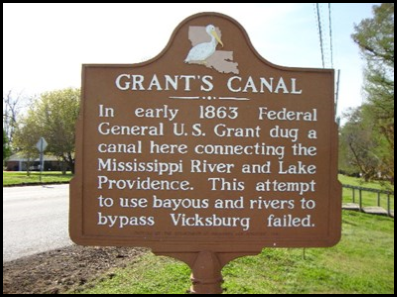

In early 1863 Federal General U. S. Grant dug a canal here connecting the Mississippi River and Lake Providence. This attempt to use bayous and rivers to bypass Vicksburg failed.

The digging proceeded and the excavated material was thrown on the east side of the canal toward Vicksburg. The Mississippi was rising. Levees large enough to use for transport of wagons were needed to protect the camps. As the water table rose steamboats had to be close by to rescue troops in case the levees broke.

When the original canal was being considered during the summer of 1862 Williams had concerns that the enemy guns could reach the work area. This information was not passed along to Grant. Lincoln was still anxious that the canal would be the answer to all their troubles of defeating the Confederates on the Mississippi. There was some discussion of digging a canal a little further upstream above the original. They talked about a trouble-making eddy in the river at the entrance and placement of enemy guns. All the discussions on digging a new canal still led to sticking with the original one.

Major General John McClernand became discouraged and looked for an alternative solution. General Sherman was also very doubtful about the canal. Grant passed along the disappointments to Major General Henry Halleck in Washington, D.C.

On January 28, 1863, an engineer was brought in for leadership, Captain Frederick E. Prime from the Corps. of Engineers. He asked for the canal’s width to be increased by 10 feet. A dredge was requested but none was available. Although this canal carries Grant’s name he was never in approval and by February 4 he and Sherman were very discouraged.

The entrance and exit of the canal were closed so it could be drained. A new entrance was started and the engineer decided to have the levees raised. 550 black laborers were put to the new entrance, the width set at 60 feet, depth 4 feet by February 12. The number of troops working on the canal reached 3,000. Illness and unsanitary conditions prevailed.

The soldiers camped along the 12 mile stretch came close to being 35,000 and many died each day. The levees became burial grounds.

February 14, saw rain, storms and flooding of camps. Work was reorganized and it was done in segments. Good news came that dredges would be coming and a steam pump started at the new entrance. General Grant saw hope at last. The two dredges arrived in early March. Grant sent a message to Major General Halleck that the canal would be ready in a few days.

Major misfortune struck when the upper dam broke and a surge of water flooded the bottom lands. Because of pressure on the canal levees, the other dam was destroyed. More work ensued.

Pemberton’s Army had been doing their preparations and on March 17 they fired trying to keep boats from going through the canal. Once again General Grant saw no hope.

By March 22 Grant believed that the boats could not go through due to the enemy firing on the exit of the canal. He had to order the removal of the dredges. A decision was made to ferry troops across below Vicksburg. With advice from Farragut, Porter sent two rams to run past the Confederates batteries. One was disabled and another sunk.

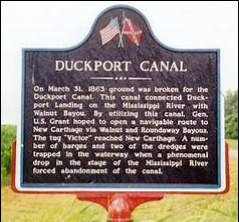

On March 31, 1863 ground was broken for the Duckport Canal. This canal connected Duckport Landing on the Mississippi River with Walnut Bayou. By utilizing this canal, Gen. U.S. Grant hoped to open a navigable route to New Carthage via Walnut and Roundaway Bayous. The tug “Victor” reached New Carthage. A number of barges and two of the dredges were trapped in the waterway when a phenomenal drop in the state of the Mississippi River forced abandonment of the canal

With a new engineer, another canal was proposed three miles up the Mississippi. This would be the Duckport Canal, 40 feet wide and 7 feet deep. The canal would go from Duckport, Louisana to Walnut Bayou, then through bayous to the Mississippi at New Carthage. From there troops would be ferried across to the state of Mississippi, north of Vicksburg. Workers with the dredges were able to remove the levee with a blast and let the water in. The removal of stumps and trees took more time. The new waterway was a total of 37 miles.

While the two canals were being finished, General Grant ordered McClernand’s men to prepare a road from Milliken’s Bend to New Carthage, north of Vicksburg.

In mid-April a tug and barges did pass through the new canal and reached Walnut Bayou. Soon the water levels dropped and the dredges were put to work.

Finally, the canal efforts failed. Some of the fault is attributed to poor timing, the wrong time of the year, flooding, illness and delays.

General Grant did get below Vicksburg by land to New Carthage. Troops were ferried to Bruinsburg April 30 to May 1. The surrender of Vicksburg came July 4, 1863 after a 45 day siege. A monument marked the spot where General Ulysses S. Grant and Lt. Col. John C. Pemberton sat on a grassy slope and made an agreement. However, the monument is now in the visitor center because visitors had been chipping away pieces over the years. A cannon barrel now marks the spot.

Both canals were failures. In the winter of 1876, the flooded Mississippi River made a new path across the DeSoto Peninsula not too far from the previous efforts and turned the peninsula into an island. Vicksburg now looked down on an ox bow lake. Decades later, the Corps. of Engineers changed the course of the lower Yazoo River so it flowed into the older path of the Mississippi and once again Vicksburg had a river front.

A short time later, President Lincoln wrote “The Father of Waters again goes unvexed to the sea.”

Grant’s Canal can be visited as part of Vicksburg Military Park. It is much smaller now and 200 yards can be viewed. My husband, Steve, and I stopped there in February to take the following pictures:

In the middle picture I am standing on the side road and looking east toward the levee. The last one is looking north toward the road and I-20.

The railroad is still elevated on the island and the town of Delta is doing okay with what looks like water and sewage and trash pick up. Saw a church and two apartment buildings along with marked streets and houses. The river was high so when we drove to the top of the levee on the north we couldn’t go out where the fishermen and boat launchers might be.

A video featuring David F. Bastian speaking to a Civil War Round Table on May 2014 about Grant’s Canal can be seen on YouTube at bing.com videos.

Sources:

Bastain, David F. Grant’s Canal: The Union’s Attempt to Bypass Vicksburg. Shippensburg, PA:Beidel Printing House, Inc., 1995.

Jones, Terry L. The Louisiana Journey.

Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/Grant’s_Canal

On line photographs and maps under Grant’s Canal and Duckport Canal.

Canal Boat Requirements, Lock Passage and Penalties

From The Revised Statutes of the State of Indiana, Adopted and Enacted by the General Assembly at Their Twenty-second Session,

Indianapolis, In: Douglas & Noel, Printers, 1838.

An act was approved on February 19, 1838, by the General Assembly of Indiana for the protection of the Canals belonging to the State, the collection of tolls thereon, and for other purposes. Last issue we presented the first part of the act regarding the destroying or obstructing of the canals. This issue we cover the requirements for canal boats and passing through locks.

Sec. 8. That no boat or float, unless it have a firm and permanent bow, at least as sharp or acute as a semi-circle, shall navigate or float on any canal of this state; and every time any boat or other float without such bow, shall move one mile or any greater distance, along any of the canals of this state, shall be considered a distinct offence.

Sec. 9. That it shall not be lawful for any boat, having any spike, bolt, nail, hook or any plank, board or pin projecting from the side, end or bottom thereof, in such manner as to be liable to injure any other boat or towing line thereof in any work or mechanical structure belonging to the canal, to navigate any of the canals of this state.

Sec. 10. That every boat running upon any canal of the state, shall have a guard or plate of iron or some other permanent device, firmly attached so as to cover and secure the opening between the keel of stern post and the rudder, thereby effectually preventing the tow line of any other boat from entering said opening.

Sec. 11. That no boat be permitted to navigate any of the canals of this state, without a good and sufficient bow line, which shall be approved of by the engineer or superintendent.

Sec. 12. That it shall not be lawful for any setting pole or shaft, pointed with iron, steel, or other metal, to be used in the navigation or management of any boat or other float on any of the canals in this state. [No pike poles]

Sec. 13. No float shall move on any of the canals of this state with a velocity exceeding four miles per hour. [Speed limit 4 mph]

Sec. 14. When a boat or other float shall be overtaken by another boat, it shall be the duty of the master or manager of the former, to turn from the towing path and afford to the latter every possible facility for passing, and to stop, if it should become necessary, until the boat or float last mentioned shall have passed by.

Sec. 15. When any boat or other float, in passing on either of the canals, shall meet any other float, passing in an opposite direction it shall be the duty of the master of each, to turn to the right hand, so as to be wholly on the right side of the centre of the canal; and the horses or other moving powers of the boat, which in turning to the right as aforesaid, shall turn from the towing path shall be stopped, so as to allow the moving power of the other, and the float itself to pass freely over the towing rope of the float so turned from the towing path.

Sec. 16. Any float moving on either of the canals, which shall have arrived within one hundred yards of any lock, in which the water is on the same level with such float; shall be permitted to pass such lock, before any float not on the same level.

Sec. 17. No person shall attempt to pass any float into any lock, or out of any lock, until the main gates of the head or foot of said lock, as the case may be, between which gates such float shall be about to pass, shall first be entirely opened into their respective recesses, nor until all paddle and culvert gates of such lock shall be closed.

Sec. 18. Neither of the main gates at the head or at the foot of any lock, shall be closed or allowed to close of their own accord, while either of the paddle or culvert gates at the opposite end of said lock shall remain open.

Sec. 19. When any float shall pass out of any lock, the main gates of each lock, through or between which such float shall have passed out, shall be entirely open and completely within their respective recesses; and all the paddle and culvert gates of such lock, shall be left closed: Provided however, that where the acting commissioner, engineer, or superintendent having charge of that part of the canal, in which such lock is situated, shall direct any paddle, culvert or other gate to be left open for the purpose of passing water through the same, such direction shall be complied with and obeyed by all the lock-keepers, masters of floats, boatmen, and all other persons concerned in navigating such canal.

Sec. 20. That in no case shall the stern or bow of any boat or float, approaching or being about to enter, or having entered any lock, be permitted to run against, or strike the head walls or either of the gates of such lock willfully or negligently.

Sec. 21. No lock gate, culvert gate, or paddle gate, shall be closed, nor be permitted by any person using the lock to close itself with such violence as to injure or be liable to injure itself.

Sec. 22. Every master or owner of any boat or other float, or any other person having charge of such float, who shall violate either of the provisions contained in the fourteen sections next preceding this section, or who shall permit any boatman or other person assisting in the navigation or management of such float, to violate either of the said sections, or any provisions thereof, shall for every such violation forfeit and pay a sum not less than five or more than twenty dollars, recoverable by action of debt in the name of the state of Indiana, before any court having competent jurisdiction.

Sec. 23. Every penalty and forfeiture imposed by this act for which any master, owner, boatman or other person may be liable, and which is herein made recoverable by action of debt in the name of the state, shall be chargeable on such boat or float, and when any suit shall be instituted for any such forfeiture, the officer issuing such process may cause such boat or float, together [with] the horses and furniture belonging thereto, to be attached and detained.

Sec. 24. Any person who shall willfully throw into either of the canals any saw-log or other timber or other thing, which may obstruct the navigation, shall on conviction thereof, forfeit the sum of ten dollars, recoverable by action of debt in the name of the state. And it shall be the duty of every engineer, collector, superintendent or agent employed on either of the canals, to seize all logs, fire-wood or other things, which may be found floating loosely, and all rafts which may be found improperly moored, so as to intercept the navigation, and to hold the same to satisfy the penalty for the aforesaid offence.

Sec. 25. If any person in navigating, or assisting in the management of any boat or other float, on either of the canals, shall either through design or negligence, in the navigation thereof, injure any lock, lock gate, waste gate, guard gate, aqueduct, bridge or other mechanical structure, shall forfeit and pay upon conviction thereof, any sum not less than five nor more than twenty dollars, and moreover be liable for all damages caused, by such mismanagement or negligence, recoverable by action of debt in the name of the state.

Canal Carries Stones to Great Pyramid

Archaeologists have uncovered new evidence that thousands of Egyptian laborers transported 170,000 tons of limestone in canal boats to the site of Pharaoh Khufu’s tomb, The Great Pyramid of Giza, in 2600 BC during its construction. They ferried 2.5 ton blocks of stone in wooden boats built with planks and rope along the Nile River and through a system of specially designed canals before arriving at an inland port, which had been built yards away from the base of the Great Pyramid.

An ancient papyrus scroll has been found that was written by Merer, the overseer, and is the only firsthand record of how the pyramid was built. In it he explains in detail how the limestone was moved from the quarry in Tura to Giza using the Bronze Age waterways. Also found was a ceremonial boat.

Archaeologists have outlined the central canal basin, which was the primary delivery area to the foot of the Giza Plateau, and have uncovered evidence of a waterway underneath the plateau the pyramid sits on.

Gronauer Lock Marker Missing

A lady who was geo-caching noticed that a tree had fallen on top of the Gronauer Lock State Format Marker. Later when she returned she found it was missing. It had been broken off its post. All that remains is its post.

She reported it to the Director of the Indiana Historical Bureau Marker Program, who in turn called Tom Castaldi, Allen County Historian and CSI Director, asking him if had information about what happened to the marker and to send photos of the damage.

Tom took photos of the post and surrounding area. He noticed that INDOT is working to expand the I-469 and Fort to Port (U.S. 24) interchange by creating a full clover leaf to relieve traffic congestion. The marker is to the south and east of a house on a cul-de-sac that may be removed for the interchange project. The tree appears to have been cut out of an adjacent crop field.

Does anyone know what happened to the marker?

W&E Aboite Creek Aqueduct Marker Installed

The new marker for the Aboite Creek Aqueduct No. 2 that carried the Wabash & Erie Canal across the creek has been erected. Tom Castaldi contacted Brian Sechler and Rick Winans, who work for Allen County and they saw to the marker installation. The marker can be seen on Redding Road in Aboite township, Allen County. We thanks these men for its highly visible placement.

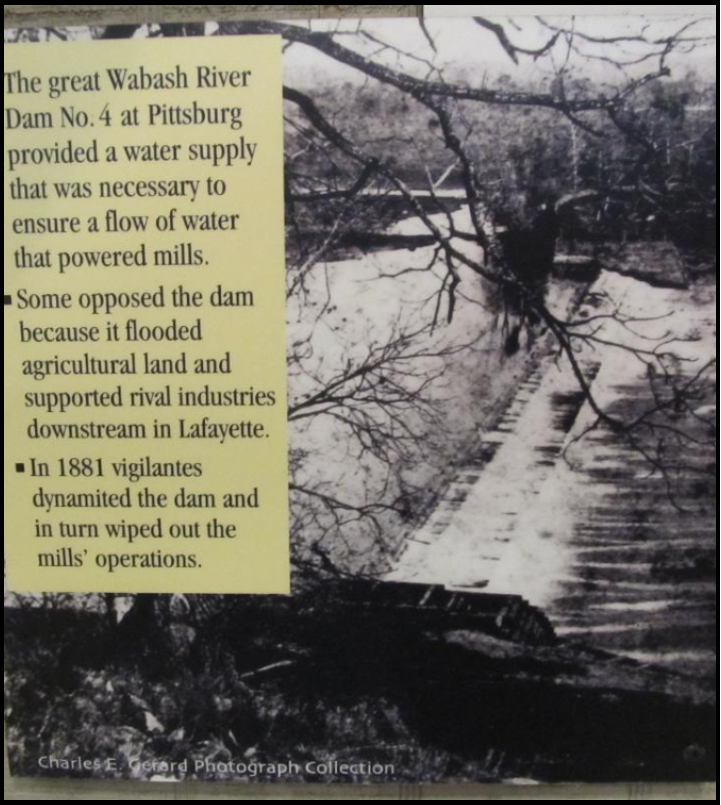

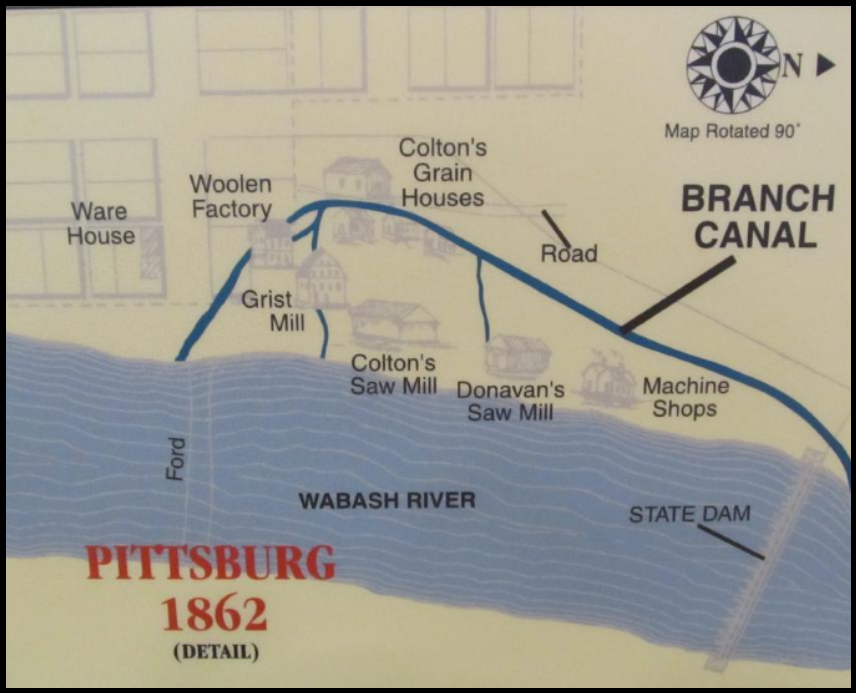

W&E Canal Wabash River Feeder Dam #4 Marker Installed

Carroll County volunteers have erected the Wabash & Erie Canal marker provided by the Canal Society of Indiana in Pittsburg, Indiana. A dam was built across the Wabash River to feed water into the main canal and into a side-cut canal. The marker was placed beside the Indiana State Format Marker for Pittsburg. Although the Wabash & Erie Canal actually was on the other (Delphi) side of the Wabash River, the dam allowed boats to cross the Wabash in a pool of water and enter a side-cut canal into Pittsburg. This type of arrangement was also made at Grand Rapids, Ohio by placing a dam across the Maumee River and diverting water into a side-cut canal on the opposite side of the river from the (Miami) Wabash & Erie Canal.

Photos by Mark Smith

Aqueduct Endangered

Rushing water after heavy rains in St. Marys, Ohio put the Miami & Erie Canal aqueduct over Six-Mile Creek in peril on April 25-26, 2019. The aqueduct was undergoing repair to its north wingwall when 4 inches of rain fell causing rivers to flood, roads made unsafe or closed, and water washing away earlier aqueduct repairs.

The St. Marys River reached a depth of 14.625 feet and no dry land could be seen between it and the M&E Canal. The aqueduct, an historic canal structure that carries canal water over the creek, is located on State Route 66.

Although sandbags and water pumps were set up in some areas, much more extensive work had to be done to save the aqueduct, which was in danger of collapsing. Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR) installed two coffer dams and limited flow at other points along the canal north of Grand Lake St. Marys, an old canal reservoir. They laid down boulders and stone across the canal about a quarter of a mile south of the aqueduct near Bloody Bridge in an attempt to stabilize the 175-year-old landmark. They dug a spillway before the first coffer dam to divert the water from the canal. When the water started spilling over that dam, they had to build a second spillway before the southernmost coffer dam and have the water flow into the same ditch as the first one to keep the canal from flooding. Water flow from the western edge of the aqueduct stopped by 9:45 p.m. and the eastern edge an hour later. Then ODNR provided security overnight. The next day ODNR crews used gravel and stone to create an access road to allow them to work on the aqueduct.

Picture courtesy Miami Erie Canal Corridor Association (MECCA)

We took these pictures this afternoon. One pic is the blocked off canal on north side of aqueduct. Bloody Bridge is shown blocked/dammed off just north of the bridge and the tow path side cut through to allow water to drain off into a side ditch. I am sending you a copy of newspaper which explains all the flooding in St. Marys. Diane April 28, 2019

Flood water six mile spillway April 26, 2019

Welcome New Members

We welcome aboard the following people have joined the Canal Society of Indiana at the single/family rate:

John & Candy Carr—Columbus, IN

Susan Gooch—Fishers, IN

Margo Finney—Carmel, IN

Chris Hanlin—Cincinnati, OH

Gronauer Lock Timber Wall

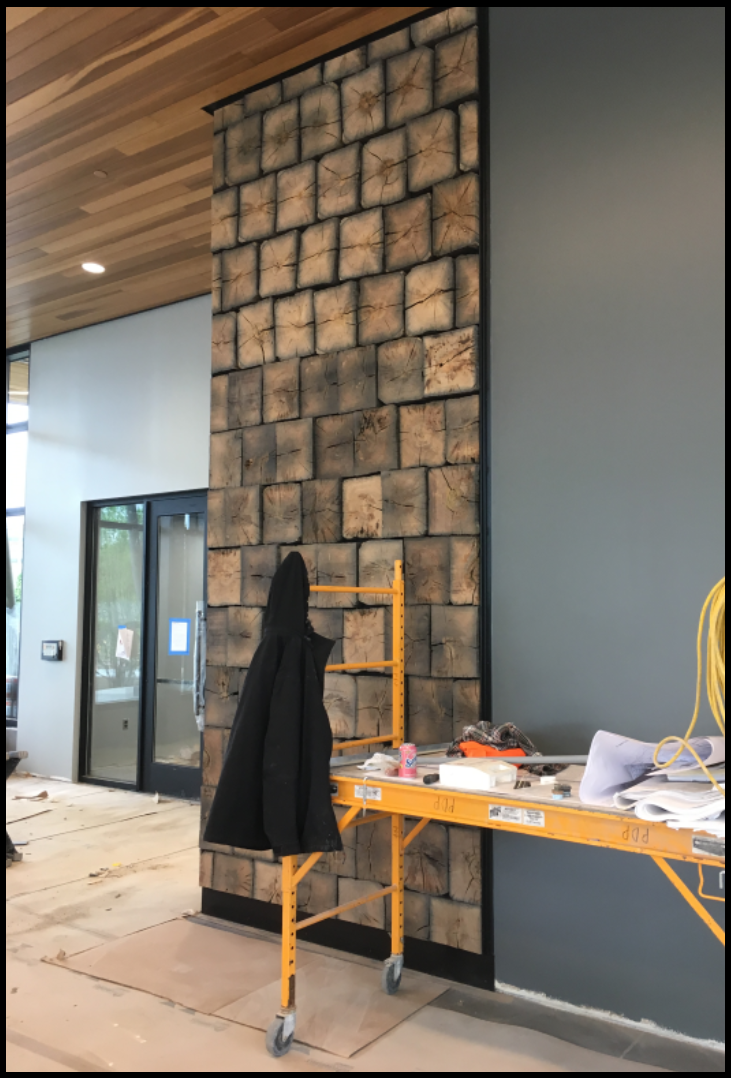

Tom Castaldi, Allen County Historian and CSI Director from Fort Wayne has sent the following pictures of Gronauer Lock timber slices that have been placed on one wall inside the new Riverfront Compass Pavilion in Fort Wayne. One photo is of Randy Harter holding a square against the wall back in April. The other three pictures were taken in May after the wall was completed. The Pavilion should be finished and open to the public by this fall.

The Gronauer Lock was constructed around 1847 and unearthed in 1991 when construction of an intersection of U.S. 24 and I-465 took place. After 172 years the hand hewn timbers still show the tree rings and are in great shape. We do not know how old the trees were when they were cut down, but closer study counting the rings may give us an idea as to their age.

Fort Wayne’s canal boat “Sweet Breeze” docks near this pavilion and carries passengers on the river. It is assumed some sort of interpretive sign will be placed by the wall identifying it and telling about the Wabash & Erie Canal, a 468-mile-long canal and the longest is North America. Ground breaking for the canal was held in Fort Wayne in 1832 and proceeded west toward Huntington, Indiana.

In Memoriam: Jean Hulslander

Sept. 19, 1927 — June 27, 2019

Photo by Bob Schmidt

Jean Caroline (Muntz) Hulslander, CSI member from Illinois, passed away on Thursday, June 27, 2019 at age 91 and was laid to rest in Grand View Cemetery, Atkinson, Illinois on July 2.

Jean was born on September 19, 1927 to E. Millard and Hilda (Keeney) Muntz in Hanover, Pennsylvania. After graduating high school, Jean attended the School of Medical Science in Boston, obtaining her degree as a Medical Technologist. She went to work at Hammond Hospital in Geneseo, Illinois, and met Gerald Huslander; they were married on December 29, 1949. While Gerald obtained his degree at the University of Illinois, Jean worked in the lab at Carle Clinic in Urbana, Illinois. She then took time off to raise their four children while they lived in Paw Paw, Illinois. After they moved to Ottawa, Illinois, she worked in the laboratory at Ottawa General Hospital.

Jean was very involved with a number of organizations, including Cub Scouts, Campfire Girls, and 4-H. Jean and Gerald also became a foster family to Robert, Diane, and Rodger Smeets when the need arose. She taught Sunday School and served on numerous committees at Trinity Lutheran Church and at the synod level. Jean was also one of the founders of the PAD program in Ottawa and volunteered there for many years. She loved sewing in all forms and was a charter member of the Illinois Valley Quilt Guild, and was a volunteer at the Historical Museum in Utica, Illinois.

In addition to her family, Jean enjoyed travel, and, along with Gerald, attended many Canal Society of Indiana tours. We will miss her. She also liked sewing and quilting, designing banners for Trinity Lutheran, teaching and helping people She was famous for her cookie baking and could be counted on the supply a number of varieties whenever the occasion arose.

Jean was preceded in death by her parents, one brother, three sisters, and one daughter, Ellen White. She is survived by her husband, Gerald, her children David (Betsy), Carolyn Kennedy (Ray Klein) and Sarah along with eight grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren.

Jean left a special note thanking her wonderful husband who took care of her, encouraged her with her projects, and showed her much of the world. “I had a good life. I am tired and have pushed these last three months until unable to do more.”

The family thanks the OSF Hospice team and the caregivers from Home Instead.

Visitation was held at the Mueller Funeral Home in Ottawa on July 2, between 5 and 7 p.m. The funeral was at Trinity Lutheran Church at 10:30 a.m. on July 3 followed at 2:30 with interment at the Grand View Cemetery.

Suggested memorials to Trinity Lutheran Church, 717 Chambers Street, Ottawa, IL 61350 or Shriner’s Children’s Hospital