- Wildcat Creek Dam & Slack Water Navigation Area

- Determining the Canal Routes In Indiana

- Canal Notes #13: Lake Wabash

- Fowler Park Marks Culvert Timbers

- The Traveling Whitewater Canal Sign

- Tagmeyer Boat Donated To Canal Museum

- W & E Map Returned

- Koehler Draws Crowd

- Canal Items On E-Bay

- House Boat Photographer On The Canal

- The Muleskinners’ Language

- Memorials Honoring Steve Simerman

- Wabash-Erie Canal Walk & Talk

- CSI Fall Tour Announcement

Wildcat Creek Dam & Slack Water Navigation Area

By Preston Richardt

Since I began my expanded research of the Wabash & Erie Canal in order to create a cohesive map of it through Indiana, Wildcat Creek, which enters the Wabash River in Tippecanoe County, Indiana just north-east of Lafayette, was an area that eluded me for some time. After reading the canal engineer’s report along with the Canal Society of Indiana’s 2007 tour information, I was confused about how the site was built and the area became somewhat of an obsession for me. My problem with this particular area was that it is near Lafayette, Indiana and I live near Evansville, Indiana some 3 to 3-1/2 hours away making regular visits difficult. But this did not dampen my interest in following the very detailed engineers’ reports.

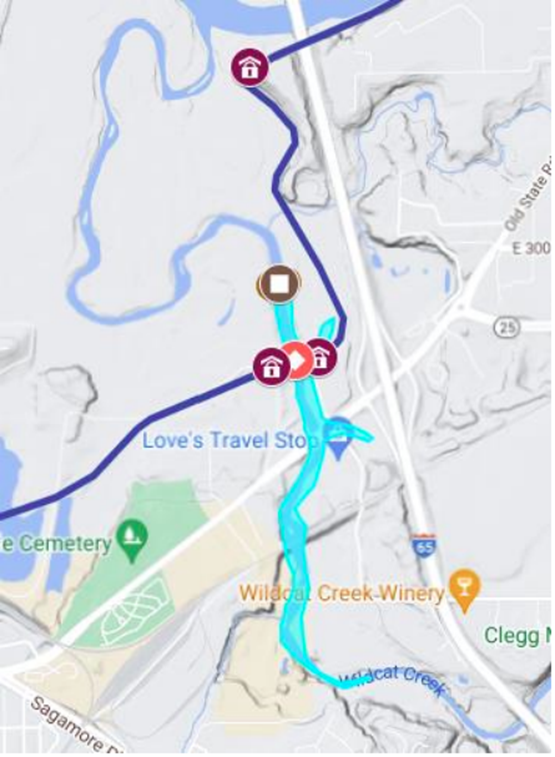

Based on my understanding of the information I had read at the onset of the mapping expedition I developed the following map.

But I never felt it was accurate. The only way I knew how to solve this was to reach out to those who have knowledge of the area and more expertise in canal structures. However, after contacting several persons who might be able to provide understanding, I found that many people were in the same boat with me when it came to understanding this area. Yes, pieces of physical evidence from the canal are still present but understanding this area would require a much more thorough research to completely grasp the engineering of the canal crossing of Wildcat Creek.

Early in 2023, I received an email from CSI Board Member Tom Castaldi inviting me to be part of a research group studying this area in more detail. The group consisted of Dan McCain, David McCain, Tom Castaldi, Ed Geswein (Owner of the property on the west side of Wildcat Creek), Mike Tetrault, Vern & Nan Mesler and me. I felt honored to be part of this group as I felt I wasn’t as well versed on the canal as the rest of the group.

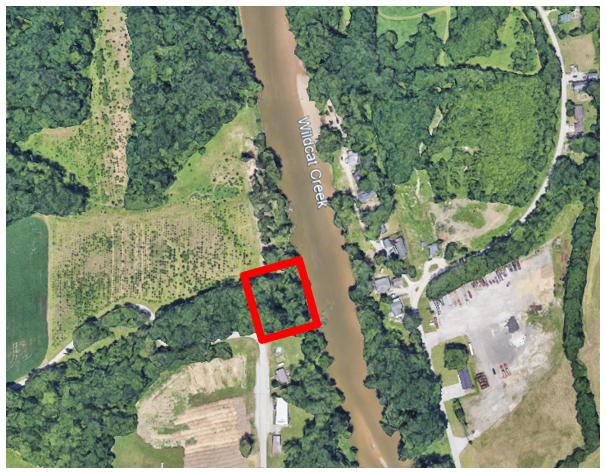

The group, minus me due to my distance of travel, met multiple times throughout the spring, summer and autumn of 2023 and made several site visits; each visit they found more about the canal as it passed through the area and, even though many questions were answered, several more would come up. The group felt they had found the location of the dam site just a very short distance below the canal crossing based on evidence found at the site (protruding iron rods out of the western bank of the stream). It wasn’t until November of 2023 that was I finally able to meet with the group at the site and discuss all they had found.

I left my home in Gibson County early on November 7th for a long drive north to Delphi, Indiana where we were to meet before driving the 20 minutes or so west to the Wildcat Creek site. Arriving shortly before 9:30 local time (I live in Central Time Zone and Delphi/Lafayette are Eastern Time Zone) we met and began the discussions about the canal as it passed through Delphi, Americus and ultimately its approach and passage through Wildcat Creek. Before leaving for the site, I quickly toured the Canal Museum at Delphi, as this was my first visit there. I was very impressed with the museum and the many hands-on exhibits for its guests, but time was short, and I needed to leave and head west to Wildcat Creek. I traveled via Old State Road 25, which added a little time to the drive, because I wanted to see Americus, which was so close by, (this is an area I will be returning to in the future for more exploration). Next stop Wildcat Creek Slack Water Navigation site.

Wildcat Creek Area

Before I discuss the canal structures built in the vicinity of Wildcat Creek, I would like to provide some basic information about the stream for those who may be less familiar with it.

Wildcat Creek is a Wabash River tributary that consists of three main forks – North, Middle and South. The stream flows from near Greentown Indiana westerly for 84 miles before emptying into the Wabash River near Lafayette. It drains an area of 804.2 square miles. A historical event occurred on its banks in November of 1812, when an American military force was defeated in the Battle of Wild Cat Creek, which is also known as “Spur’s Defeat”. (source wikipedia)

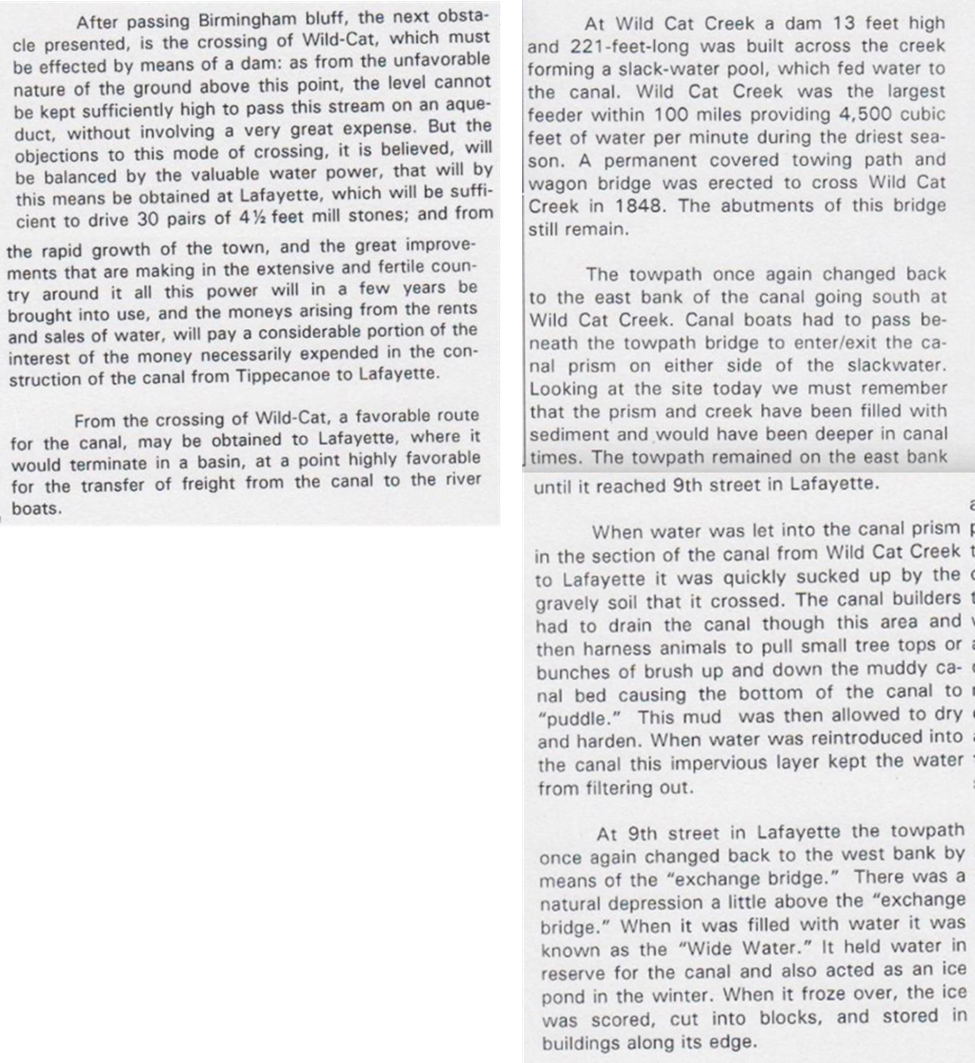

This area just above the creeks mouth with the Wabash River, was the site of a dam and slack water navigation for the Wabash & Erie Canal. The canal boats would utilize the slack water pool created by the dam to travel some distance before returning into the canal prism or to provide a means of crossing a stream without the requirement of an aqueduct. In some cases, these pools would provide water for the canal. In this case the engineers decided to utilize the pool for both the purpose of crossing the stream and for supplying the canal with water. This was the main pool for keeping the canal watered down to Parke County’s Coal Creek near Lodi, Indiana.

Lets Talk Structures

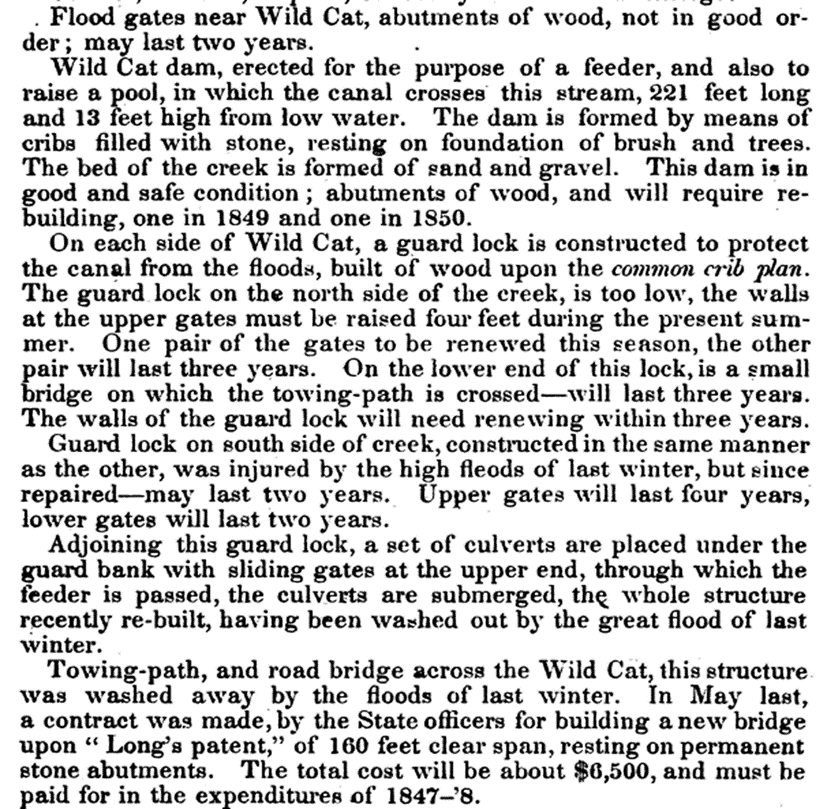

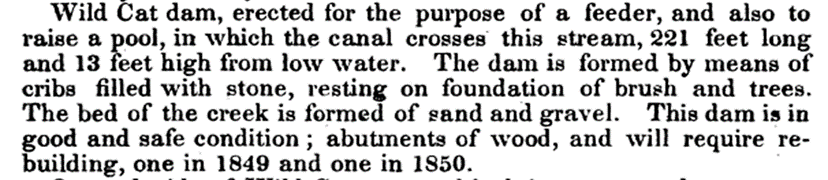

Below is an excerpt of the 1847 Engineer’s Report detailing the area around Wildcat Creek…

The following description is from the CSI 2007 Tour “Canalabrating Good Times” describing the same area…

Towing-Path and Road Bridge

After arriving at the site and meeting the property owner, Ed Geswein, we were taken to where the west side towpath and road bridge abutment are located. The abutment is showing some signs of aging and will need some reinforcement in the not-so-distant future to the southeast corner of the structure, but the rest of it is in excellent condition as can be seen in the photograph. At the west end of this abutment, it appears that concrete was poured over large rocks. This indicates a turn of the century (circa 1900) attempt to reinforce the earthworks as a means of erosion control.

From the stone abutment looking east across the creek remnants of a concrete abutment are visible and future investigation of the area will be needed to determine if any cut stone is still present nearby.

In this same area it appears that dredging has occurred causing the canal to be much deeper against the creek. It is offset to the north considerably, but a few steps to the west the canal prism becomes clearly visible again.

Rods and Stones

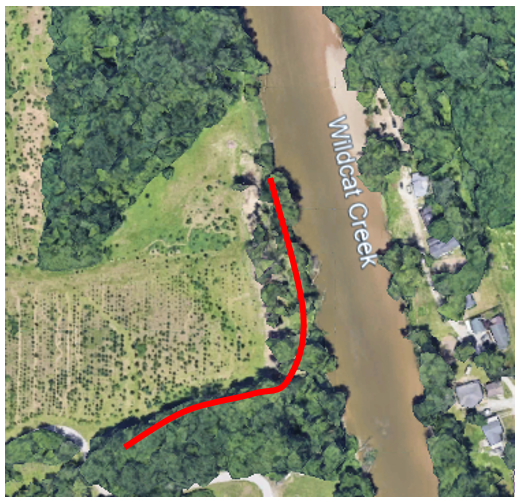

We left this section and proceeded north on Conservation Club Road, which crosses the canal at an s-curve before dropping in elevation to the floodplain of the creek and Wabash River. After crossing the canal on the county road, we turned back east toward Wildcat Creek, and as we approached the stream, Ed pointed out the berm side of the canal and how it turned to the north as it approached the bank of the creek. I found this interesting, and I will discuss this berm later in this article.

We were taken to what was thought to be the location of the dam across the creek, based on the previous visits throughout the year. This location had several wrought iron rods that extend out from the embankment. These rods were threaded with nuts on several of them. Additionally, there was a lot of stone in this area of the bank. The original thought was that the rods were bank anchors for the dam. The issue I had with the rods is that they appeared to be machined threads and not hand threaded. Each bar was uniform in thread size and depth. Also, I had not seen any location along the Wabash and Erie Canal where they used this type of anchorage in a dam site. In the 1847 audit; Jesse L. Williams reported that this dam was made of the wooden crib design and filled with stone, no mention of rods listed anywhere, which he does state when used in other canal structures. Below is the 1847 engineer’s report for the Wildcat Creek dam…

The only thing that led me to believe this might be the location is the amount of stone on the bank.

I decided to continue looking over the area. Downstream (north) from this location I noticed another area with a large amount of stone along the bank. We proceeded to the spot in question and after investigating it found that it did not look right for the dam either. Upon further observation downstream I saw another outcropping of the bank with very large rocks extending into the creek for some distance.

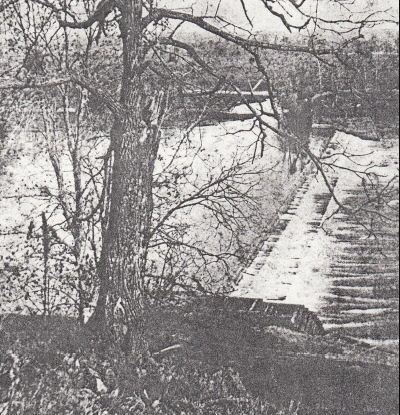

Stones and Timber

Walking to this second location and climbing into the bed of the creek, I immediately noticed straight edges coming from inside the bank, which abruptly stopped at a squared off end and then an additional squared off object extending into the creek for approximately 10ft with a gap between the two more squared ends. The gaps were approximately the same distance as the objects were wide, approximately 12 to 16 inches.

Using a sophisticated tool (aka a stick) to differentiate between stone and wood, I was able to determine these objects were indeed wood. I immediately called to the group that I had found timbers which led Tom Castaldi to excitedly scramble down onto the outcropping of land I was standing on to see for himself. Unfortunately, due to the lighting in the area I was unable to obtain a photograph of the logs extending out into the stream. However, as I proceeded across the rock pile, I found timbers laid side by side in the water as photographed here.

The Dam Site

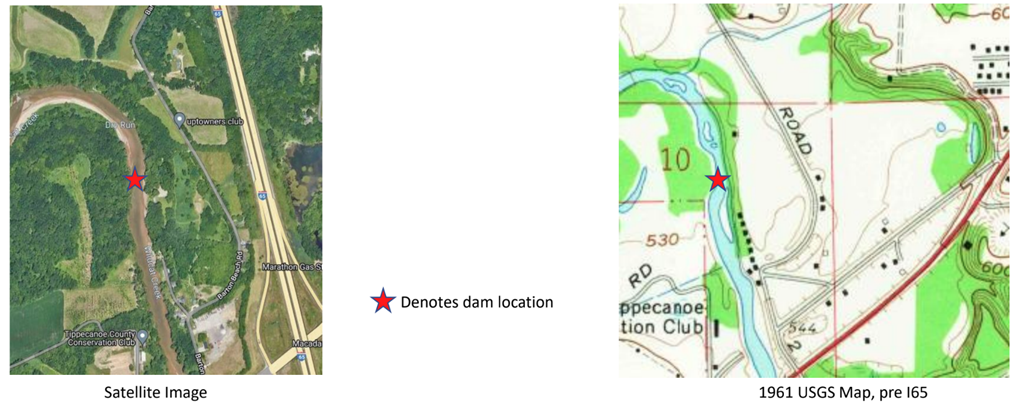

Having identified where the dam site is based by the physical evidence, I began to ask where the far (east) high ground was located that would prevent the water from flowing around the dam. For this I needed to drive Barton Beach Rd and study maps.

I drove down Barton Beach Rd and found the east side of the roadway was higher than that on the west, the question became how much of this resulted from the construction of Interstate 65. To answer this, I would need to study topographical maps of the area before the interstate was built. The map I was looking for was the 1961 USGS map of the area as seen above.

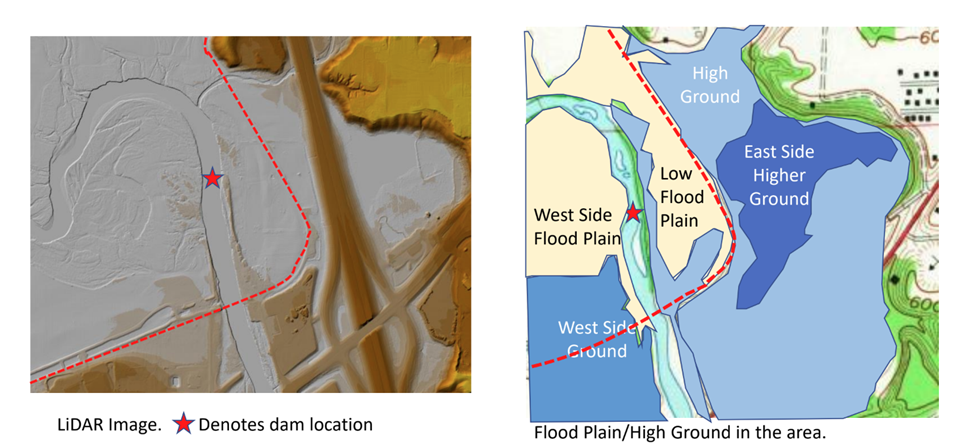

High Ground vs. Flood Plain

Using modern Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) mapping, locating the route of the canal was quite easy. With the use of the LiDAR map in concert with the 1961 USGS map I was able to accurately identify the high ground in the area before the interstate was, built which helps us better understand the pool of Wildcat Creek and the canal crossing at this site.

Based on the topographical information, we can now see how the pool above the dam was impounded from the east. What keeps it in the desired location on the west? Now we have to revisit the topography on the west side of the creek.

Creek Side Berms

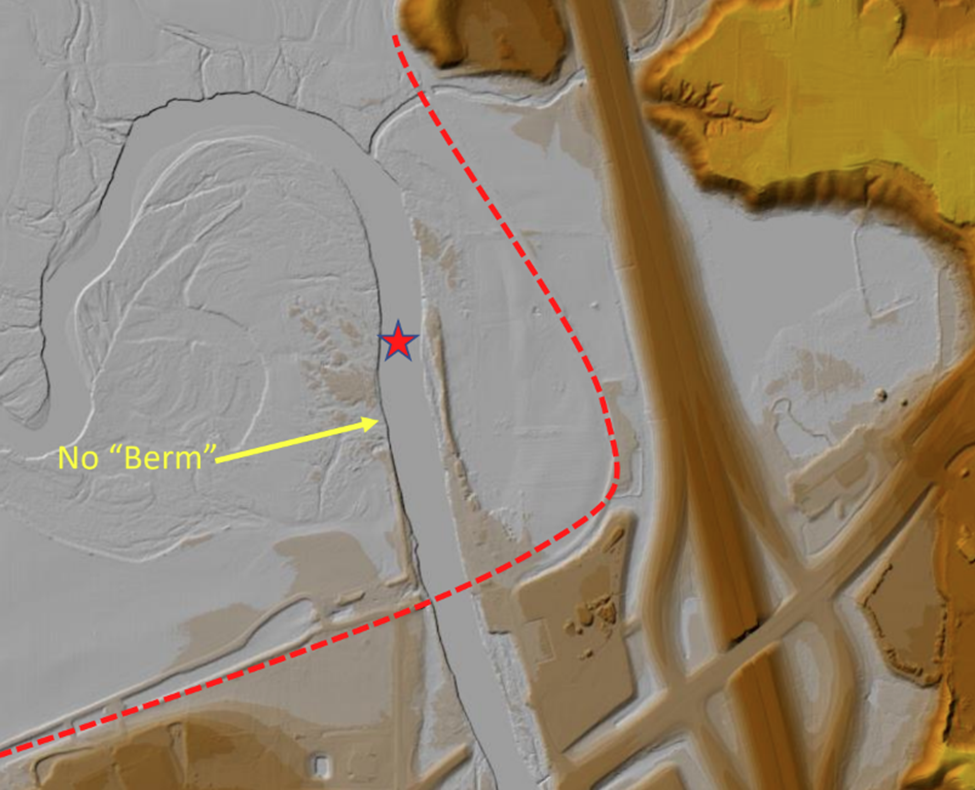

If you recall I mentioned previously I would discuss the berm’s northward turn on the west side of Wildcat Creek, well here we go…

My first thought when Mr. Geswein asked me about the berm that was parallel to the stream and was part of the Lafayette levee system put in by the Corp of Engineers well after the canal was abandoned, but after reviewing the LiDAR evidence I came to a totally different conclusion.

Before I get too far ahead of myself, I need to explain the difference between LiDAR and topographical maps. Topo maps, as they are more commonly referred to provide elevation changes in essentially two different elevation increments; 10 feet for non-mountainous areas and 100 feet for areas that are considered mountainous. So, when reading one of these maps in Indiana or the Midwest for that matter the distance between lines represents 10 feet in elevation gain or loss. That is why sometimes you are able to see subtle elevation changes from a satellite image that are not on topo maps. The problem with satellite images is you cannot see through trees. LiDAR is different, it uses light from a pulsed laser to measure variable distances to the Earth and is much more precise. Its elevation changes are accurate down to a meter (39 inches) in most cases. Additionally, LiDAR can see the Earth through heavy vegetation giving us a better idea of the surface topography in a given area. Now back to the story of the Wildcat Creek site…

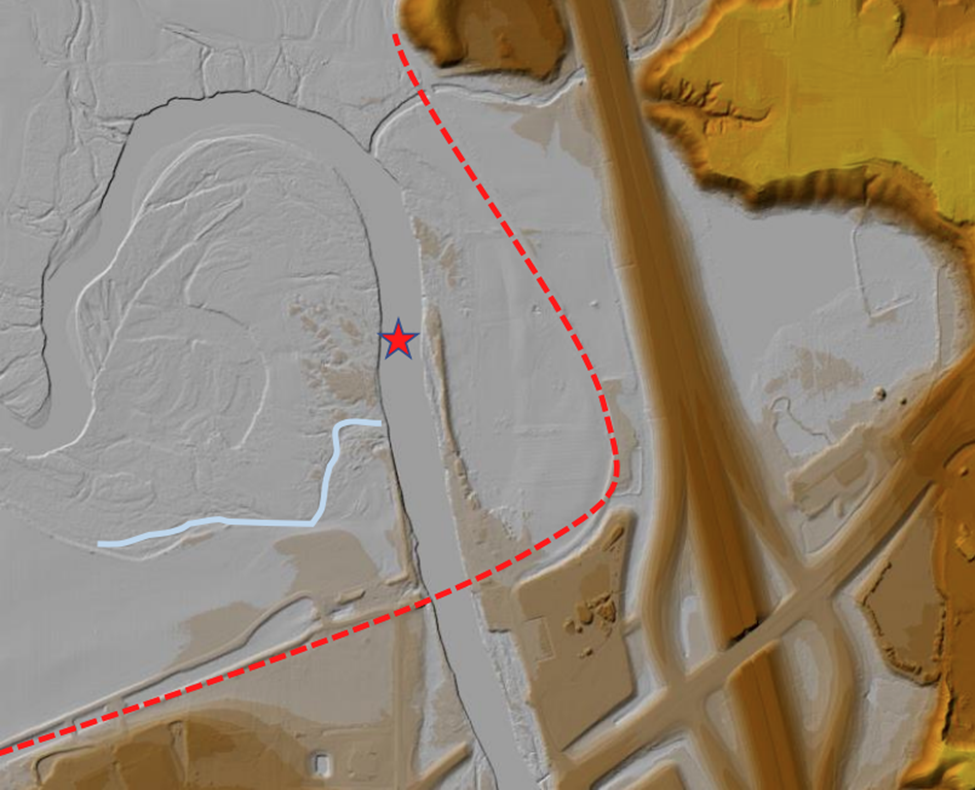

Using LiDAR, I was able to identify the berm Ed was asking about on his ground located on the west side of Wildcat Creek. I noticed a long narrow “ridge” that lay between the stream and the field and how that ridge tied into the canal berm as the prism took shape west of the stream (pictured above). Additionally, I noticed a similar berm existed on the east side of the creek (pictured below) which led me to the following conclusion. It is my belief that these berms were built as part of the dam on Wild Cat to keep the pool inside the creek bed as much as possible.

When you compare these two berms with the location of the wood found in the stream, the dam location, it is unmistakable as to their purpose. So now the question is why does the west side “berm” not extend to the dam site?

The “berm” was removed to allow for faster drainage of the low land on this side of the stream. In fact with LiDAR you can see a small stream that flows into Wild Cat Creek at this point. This led me to another question; what are the iron rods in the embankment and why is there so much stone there?

Rods

The rods appear to be part of a structure that once stood along the creek in this area that was part of the “Barton Beach,” or a more plausible thought is to hold the bank in place to prevent erosion as it appears the flow of the stream swings to the side and has eaten away at the bank. This is evidenced by sand bars on the east bank that would force the water to flow to the west bank thus eroding it. We may never know for sure what these were used for, but these are my best guesses.

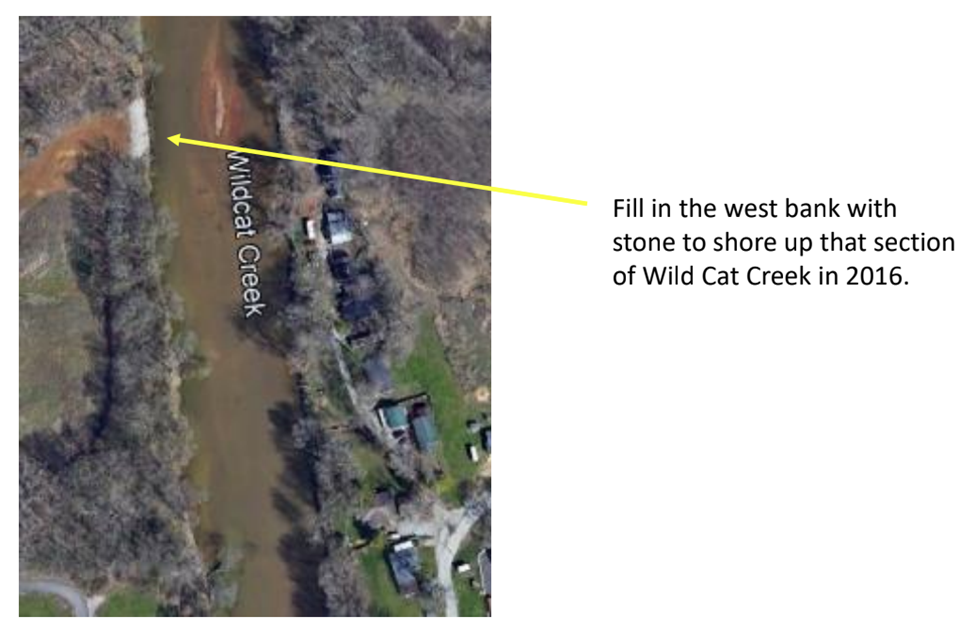

So now the question of how the stone got there is a much simpler answer to find, and I used Google Earth to provide the answer…

Where did the Stone Come From?

In the pictures above you can see the treeline extended north and I believe the berm was partially still there, but in 2015 something happened that caused the owner to have to remove the trees in this small area, for this I turned to the property owner Ed Geswein…

Mr. Geswein explained shortly after taking ownership of this property, during the winter of 2015/2016, Wildcat Creek froze over and ice dams were formed causing the stream to backup. He further explained that the flooding was so severe that local officials feared the Indiana 25 bridge would fail. The bridge did not fail, but after the water receded it was found that a large section of the west bank (the same area that the drainage had been for the field) had washed away. He and a neighboring property owner had to obtain permits to shore up the stream bank. They brought in dirt and stone to prevent further damage from occurring. This explanation provided the answer to where the stone had come from.

With the dam location being identified in Wild Cat Creek, I came home and redrew the pool of the slack water in this area based on the information found as shown here.

Conclusion

I would like to thank Tom Castaldi for inviting me to be a part of this amazing group. It has been and continues to be an honor for me to be considered knowledgeable enough to be included in the research and discovery of the canal and its structures throughout the state.

Through the experience and knowledge of how canals were built and understanding the area we were able to put some of the mystery around Wildcat Creek slack water navigation to bed. Even though more questions in this area remain a mystery, at least we were able to identify the following features of the Wild Cat Creek Slack Water Crossing:

- The location of the towing path/road bridge over the pool (slack water) of Wild Cat Creek,

- Understand the topography of the land and how it was utilized to form the water supply for the canal,

- How the engineers overcame the floodplain of the creek and the river to maintain a pool behind the dam, and

- Most importantly the location of the Wild Cat Creek Dam.

Hopefully, this group will continue to explore the area and make new discoveries so all the questions surrounding it can be explained for future generations of canawlers.

Determining the Canal Routes In Indiana

By Robert Schmidt

For early settlers in the American colonies, rivers were the preferred highways of commerce vs. primitive unimproved roads. Where the pioneers found barriers such as rapids and falls in the rivers, they attempted to build waterways or short canals around them. Such was the case when the Indiana Territory was created in 1800. The rapids on the Ohio River at Clarksville were a barrier even for flatboats heading downriver toward New Orleans. The early attempts by the Territory and later the state of Indiana were unsuccessful to circumvent the falls. By 1830 Kentucky at Louisville had won the contest by constructing a bypass canal route that is still there today.

With his surveyor background, George Washington looked at maps of the Maumee and Wabash River watersheds and suggested that a canal could possibly be built where these waterways joined. That was a bold suggestion since the area was occupied by the massive Indian village “Kekionga.” It wasn’t until the Indians were defeated by Anthony Wayne and later, after the Erie Canal was begun, that Indiana began thinking about a canal at that location.

What are the Criteria that Determined the Route of any Canal?

An essential element is a water source. At the highest point/summit level there must be a water source that can supply a channel wide enough to provide hydro-power or carry commercial traffic. Due to absorption and evaporation the original water source must be supplemented as the length of the canal increases; therefore the canal must also closely follow other supplemental water sources. Reservoirs can be built at the summit or along the route to store a supply of water as well.

The route selected determines the financial cost and labor force required in digging the channel. The infrastructure needed in the form of locks, aqueducts, culverts, bridges, etc. all add to the cost of labor and material. Who is going to pay for it?

Politics also play a major part in determining canal locations. In the early 1800s practically every community wanted to have a means to connect their community with the outside world to improve commerce, thus it became a struggle in the Indiana legislature as to which area would get a canal.

The War of 1812 demonstrated the need for moving troops to defend the country both from British attacks along the northern border with Canada and from the south at New Orleans. A connection with Lake Erie at both the east end at Buffalo and the west end near Toledo seemed to favor a canal that effectively would connect the Lake with the Wabash River and possibly the Ohio River in southern Indiana.

A Federal grant of lands that could be sold to finance such a canal seemed the logical choice to fund a canal of national importance. Politics played a role at both the national and state levels. The Whig party, nationally led by Henry Clay, favored internal improvements, but the Democrat party thought such projects as the Wabash Canal should not be funded by the federal government. The 1827 land grant was only approved by a few votes, just before the 1828 election of Andrew Jackson. Besides overcoming Jackson’s avid anti-internal improvement administration, the bulk of Indiana’s population was located along the Ohio River and in the Whitewater Valley. To get the Indiana Legislature to accept the federal land grant meant that those areas had to be persuaded to build a Wabash & Erie Canal in the remote area of northern Indiana.

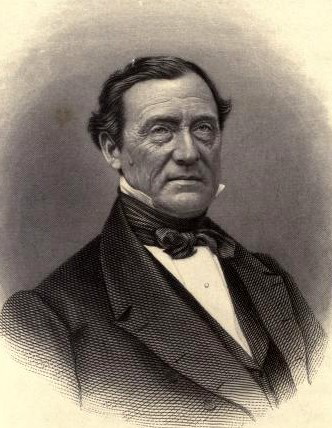

With this background and selection criteria, how was the route of the Wabash & Erie Canal finally determined? Once the political hurdles were overcome, a Board of Commissioners was established in May 1830. One of their first tasks was to find a Chief Engineer to finally agree on the proposed Wabash & Erie Canal. They hired 30-year-old Joseph Ridgeway, who was working on the Licking Summit of the Ohio & Erie Canal near Columbus, Ohio. Having just gotten married in November 1828, he was reluctant to go to Fort Wayne. He finally agreed and arrived in August 1830 to review the preliminary plans that had been proposed. Since Ohio was involved with a border dispute with the Michigan Territory, the Buckeye officials were not willing to proceed with their canal along the Maumee River. The Commissioners asked Ridgeway to layout the canal for the 35-mile-long middle division extending from the Fort Wayne summit to the mouth of the Little River west of Huntington, Indiana. Ridgeway completed his work by the end of September and prepared a detailed summary that was presented to the Indiana Legislature on December 6, 1830. Ridgeway returned back to Ohio to his old job, which had been temporarily occupied by 23-year-old Jesse Lynch Williams.

The Ridgeway report was finally accepted by the Legislature on January 9, 1832 with an estimated cost of $1,081,970. In June 1832, the Commissioners hired Jesse Williams to be the Chief Engineer of the project. Williams, who had just gotten married in November 1831, brought his 22-year-old bride, Susan Creighton, with him to Fort Wayne. The Wabash & Erie proceeded to be built west reaching Huntington by 1835 and Wabash, Peru and Logansport by 1837.

From a family photograph

In June 1833 Lazarus Wilson, age 38, who had been an engineer on the National Road through Indianapolis, came to Fort Wayne to work with Williams on canal engineering. That month he had married 19-year-old Mary Barbee. The Williams and the Wilsons became great friends.

In June 1835 President Andrew Jackson ended the Ohio/Michigan border dispute by signing a bill that authorized statehood for Michigan if it would give up its claim to the Toledo strip. This meant that the terminus of the Wabash & Erie canal would be at the mouth of the Maumee River. In turn, Michigan gained control of the entire Upper Peninsula.

In mid-1835 Jesse Williams asked Wilson to layout the canal east of Fort Wayne to the Indiana/Ohio state line. Plans were underway for building canals throughout Indiana. Williams felt that the canal east of Fort Wayne should be built wider to accommodate heavy traffic. He also knew that feeding that portion of the canal from just the St. Joseph River would create a heavy demand for water. He instructed Wilson to prepare two canal routes to the state line with an Upper more inland route and a Lower route closer to the Maumee River. Remember one criteria for a canal of any length is to stay close to a water source, but not too close to face the impact of flooding.

Both the Upper and Lower routes followed a higher route out of Fort Wayne and began at Taylor’s lock just east of town. That lock is the eastern end of the Summit level, which extends southwest to the Dickey Lock at Roanoke, Indiana. Wilson measured his miles for the Upper Level from the mouth of the St. Joseph Feeder to the Taylor lock = 2 1/2 miles + 19 1/2 miles from Taylor’s to the state line = 22 miles. For the Lower Level it was 2 1/2 miles + 21 1.2 miles or 2 miles further and they would need to construct 2 additional lift locks for 16 feet of lift, a guard lock and a 10 ft. high dam. Five and one-half miles would be on the lower level along the Maumee. The proposed dam on the Maumee at Bull Rapids. Ohio would also have to match the level at Indiana’s lower level, which would be a problem. The estimated Indiana cost comparison was:

Lower Level = $245,817

Upper Level = $154,113

$ Variance = $ 91,704

The reason for following the Upper Level is shown clearly in the numbers, plus, by 1837 when construction started, Ohio said they were building to meet the Upper Level at the State Line west of Antwerp.

Jesse Williams wanted the Taylor lock east of Fort Wayne to be built of stone that could be shipped in from Lagro, Indiana by canal boat. Today that stone lock is beneath the railroad tracks behind Deister Machine Company, 1833 E. Wayne St., Fort Wayne. For lack of stone the Saylor Lock #1 and Gronauer Lock #2 were built of timber.

As I have only shown how the route of one portion of the Wabash & Erie Canal was built, please see a more detailed report of William’s concerns and Lazarus Wilson’s report on pages 255-261 of the 1835 Indians Senate Journal that can be found on the internet. The CSI website has biographical histories of Joseph Ridgeway, Jesse Williams and Lazarus Wilson.

Canal Notes #13: Lake Wabash

By Tom Castaldi

Moses may have parted the Red Sea for the Israelites, but Jesse Williams had to change a river into a lake. As Chief Engineer for the Wabash & Erie Canal, Williams was faced with a legislative order to cross his water-filled canal over hundreds of feet of Wabash River water.

In dry periods, the water level of the Wabash is the epitome of serenity and gentleness. But during the seasons of heavy rains the water rises challenging the river’s capacity with a deep churning undertow, rushing along its ancient course. In spring, as temperatures begin to rise, melting ice breaks into enormous solid slabs that insanely crush all that lay in its path.

Williams considered three sites to cross the river. At Logansport an island in mid-stream offered a solid footing for two stout aqueducts. At Georgetown, a limestone bed and a wide river basin meant building a long aqueduct of 500 feet or more that would be very vulnerable to the pressures of the river.

Photo by Bob Schmidt

Finally, at Pittsburg, north of Delphi, Indiana, a dam 590-feet long and 12-feet high capable for forming a lake was constructed in 1838. About five miles upstream on this “Lake Wabash,” at Carrollton, canal boats arriving from Ft. Wayne and Logansport could gently glide out of the canal into deep still water. Towing animals crossed a river bridge then tugged at the lines that towed boats back into the canal on the other side bound for Delphi or the Ohio River.

Courtesy of the McCain Scrapbook

The Pittsburg dam withstood the ravages of the river, but not that of public opinion. By 1880 the railroads had rendered the canal obsolete, and the old Wabash & Erie was blamed for ills of all sorts. Instead of being filled with water moving boats with goods into the region, it became a dumping ground for the wastes of the prosperity it had helped create. Like Moses’ militant pursuers, Williams’ dam had its detractors. In 1882 an army of disgruntled locals dynamited the structure. A fiery explosive act drained the lake forever let their water go.

Fowler Park Marks Culvert Timbers

By Sam & Jo Ligget

The Vigo County Parks & Recreation Department put up a new sign in Terre Haute’s Fowler Park on the canal timber display from Culvert #151 of the Wabash & Erie Canal Cross-cut once located at Little Honey Creek. The sign, donated by the Canal Society of Indiana, was mounted on the shelter covering the timbers. A big thank you to Adam Grossman, Director of Vigo County Parks & Recreation, and his assistants Fred Grayless, Harvey Barnhart and Bill Eyre for their efforts in getting this sign put up during inclement weather.

The conditions at the time the sign was erected were terrible. We had 10 days of below freezing temperatures with the lowest being –5 degrees. We had strong winds and snow three times, but never more than 2 inches at any one time.

The sign really looks good. Its design fits in with the overall theme of the pioneer village and adds to the knowledge of local history in the area. It complements the other informational signs about the canal, which are posted at the site of the timbers.

The Irishman’s Covered Bridge sits next to the timbers from Culvert #151 in the park. This bridge was moved to this site from where Eldridge Road crosses Honey Creek. The bridge was built in 1845. About 300 feet north of the bridge would have been another bridge on Eldridge Road over the Cross-Cut Canal. Culvert #151 was about 1 mile west on the canal from the covered bridge. How appropriate that the timbers and the bridge sit next to one another at Fowler Park all these years later!

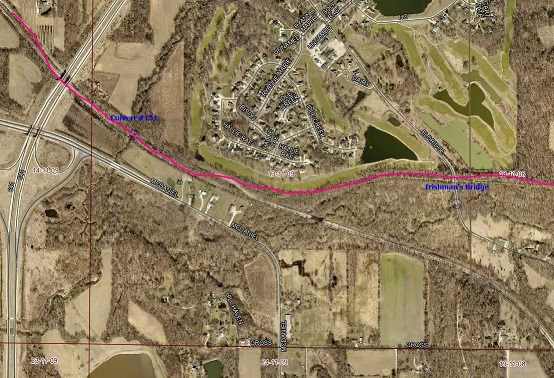

The route of the Wabash & Erie Cross-Cut Canal is shown in red through the area southeast of Terre Haute. Some of the prism is tree lined and still watered. The original location of the timbers of Culvert #151 at Little Honey Creek is marked in blue on the left and the Irishman’s bridge is also marked in blue on the right. The Terre Haute bypass is on the left with the interchange for McDaniel Road. Eldridge Road is by the Irishman’s Bridge’s former location.

The Traveling Whitewater Canal Sign

By Phyllis Matthies, Cambridge City CSI Director

The new Whitewater Canal sign traveled in the Schmidt’s vehicle to the north side of Milton, Indiana, where the canal path crosses IN SR 1. Bob asked the landowner about putting the sign on Bob’s posts, in front of the owner’s low wooden rail fence on the east side of the road. A perfect place! Arrows point south to Lawrenceburg and north to Cambridge City. But… one arrow was also pointing into the paving company driveway.

Unanticipated by Bob were motorists driving into the paving company’s private entrance looking for the canal! The huge dump trucks of the business did not need traffic on their drives, a liability to the company, so Bob’s sign was pulled up on the posts and later taken to the porch of the Cambridge City town hall, because it was reported in the newspaper that the sign had been ’stolen’ when it suddenly disappeared and that it could be returned to the porch.

The paving company had no idea who to contact, but the town clerk did.

CSI director Phyllis Mattheis was called. She picked up the sign and posts in her van and spent some days looking for a better place for the sign. She attended the Milton town board meeting, taking the sign and asking for suggestions, one of which was the gazebo park. Residents learned much more about the WW Canal that had traveled through the east side of their town in the 1840s. The meeting was taped for broadcast on the IU East community TV. More publicity for The Canal Society of Indiana!!

The town-owned gazebo park on the east side of SR 1 was considered. They tried shifting the sign in different areas there, but it just didn’t work because of the arrows.

Attending another town board meeting with the sign brought more publicity for CSI. It was felt that placing the sign on town property would bring pride to the residents and good surveillance. In the meantime, the signtraveled to downtown Cambridge City to the sign company for the year of the canal (1845) to be applied in reflective green numbers, in contrast to the white lettering on the brown sign.

As too often happens, the local brick school building has been removed, and the town owns that whole town block and plans to make it into a playground/park eventually. However, the huge stone entrance to the school has been saved and reconstructed. New streetlights enhance the sidewalk along the west side of SR 1. The town board agreed to install the CSI sign on one of the light posts, so the arrows point in the correct directions and the streetlight makes it readable at night. The canal prism lies just a couple of blocks east of SR 1, so when you are traveling through Milton, Indiana take a little detour to see the route of the canal, (best seen from the Seminary Street bridge). The tall utility poles mark the line of the canal through town and south. They are also at the north edge of town where they cross SR1 and a west side field and head north. Another section of the canal has been preserved just a little north of Milton, along the west side of Boyd Road, which becomes Center Street in Cambridge City. The Whitewater Canal was constructed to the National Road (now US 40) in the 1840s. Let’s hope the new sign has stopped traveling for now.

Tagmeyer Boat Donated To Canal Museum

By Carolyn Schmidt

Nate Tagmeyer, deceased board member of CSI and CSI artist, carved a canal boat out of an old timber from the Hedekin House in Fort Wayne, Indiana. This old canal inn was built in 1843 (the year the Wabash & Erie Canal was opened from Lafayette to Toledo) by Michael Hedekin, who was quick to see the possibilities of trade from the canal nine years after his arrival from Ireland in 1834. This three story brick structure with balconies was built on ground that had been a part of the Old Fort site. The second floor balcony hosted many early prominent leaders. The hotel had thirty-four guest rooms each of which had a knotted rope to escape fire. The first floor was used for business and had a wide staircase that took visitors up to the second floor lobby. At the front of the second floor were two large rooms. The basement kitchen had a spit large enough to roast a side of beef.

For further information about the Hedekin House and Michael Hedekin go to the CSI website indcanal.org and under The Hoosier Packet of February 2011 you will find the article “Michael Hedekin and the Hedekin House.”

After the Hedekin House fell via a wrecker’s ball in April 1969 to make way for Fort Wayne’s Civic Theatre, Nate took home a timber from the wreckage. He later carved a canal packet/passenger boat with a small figure of a man standing at the tiller of the boat. He brought it to a CSI meeting to display his work.

Photo by Bob Schmidt 2011

Years later, when he and his wife, Aleda, moved to a retirement center, he contacted CSI headquarters and asked if we would see to it that it went to the Canal Interpretive Center in Delphi, Indiana. When Bob and Carolyn Schmidt picked up the boat they asked the Tagmeyers if CSI could use it for canal displays and talks. They agreed as long as it was given to the Canal Museum when we no longer used it. Since then CSI has received smaller boat models that were easier to transport for canal talks so Nate’s request has been honored.

On February 29, 2024 Bob Schmidt presented Mike Tetrault, the executive director of Carroll County Wabash & Erie Canal, Inc. with Nate’s canal boat. It will soon be on display.

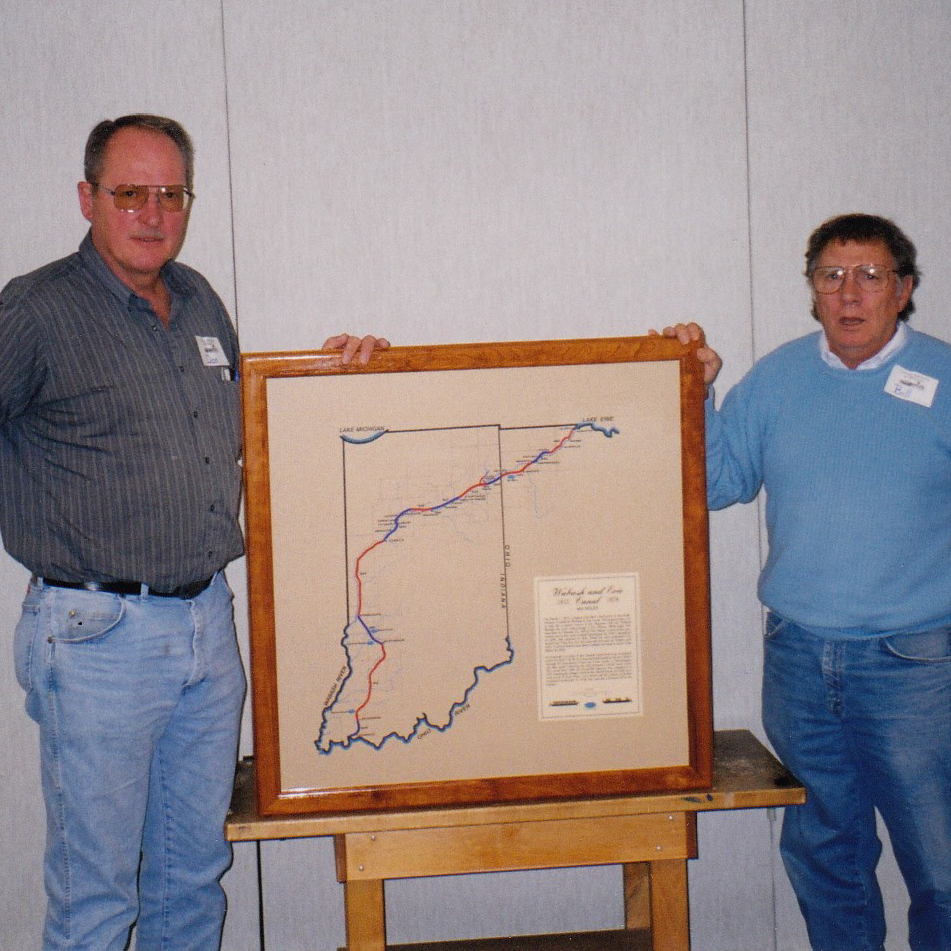

W & E Map Returned

By Carolyn Schmidt

The map of the Wabash & Erie Canal, which was used in the CSI video “The Wabash and Erie Canal: Where Frogs Their Vigil Keep” has been returned to CSI headquarters. After the video was completed, it was decided by the CSI board that it would be of more educational use if it were mounted under glass, framed and placed in Delphi’s Canal Park.

Photo by Bob Schmidt 1999

In 1999, Bill Davis, deceased director of CSI, planed a rough piece of Indiana native cherry to a thickness of 7/8” x 2” wide x 40” long and cut it into four boards. He used a router to sculpture the boards on its inside and outside. Each board was made to accommodate the map, the glass and the cardboard backing. The ends were miter cut for crisp corners. He then Minwaxed it with clear polyurethane.

Once the Canal Interpretive Center was opened if Delphi, it had larger and more detailed exhibits. The framed map was no longer displayed. CSI headquarters asked if we could have it back and put it to use. Bob and Carolyn Schmidt picked it up on February 29, 2024 when they delivered Nate’s canal boat to the Interpretive Center. We thank them for returning it.

The map shows the route of the canal from Toledo, Ohio to Evansville, Indiana in red and blue segments with dates on which the canal segments were completed. A quick look at the map and one easily sees that the canal was completed from Ft Wayne to Roanoke by 1834-35, Huntington by 1835, Lagro by 1836-37, etc.

Koehler Draws Crowd

At 1:30 p.m. on March 9, 2024, Clay County Historian and CSI Director Jeff Koehler from Center Point, Indiana presented a program on “Interurbans” to a packed house at the Vigo County History Center in Terre Haute, Indiana. There were 105 people present including CSI Directors Sam and Jo Ligget of Terre Haute.

Jeff is very interested in transportation in early Indiana. This has led to his research into the interurban that ran through Vigo County for four decades in the 20th century as well as his research on the Wabash & Erie Canal and the Cross-Cut Canal. His talk related little known facts and stories about this early mode of transportation, how it connected remote areas to urban areas and how it was much faster than canal travel.

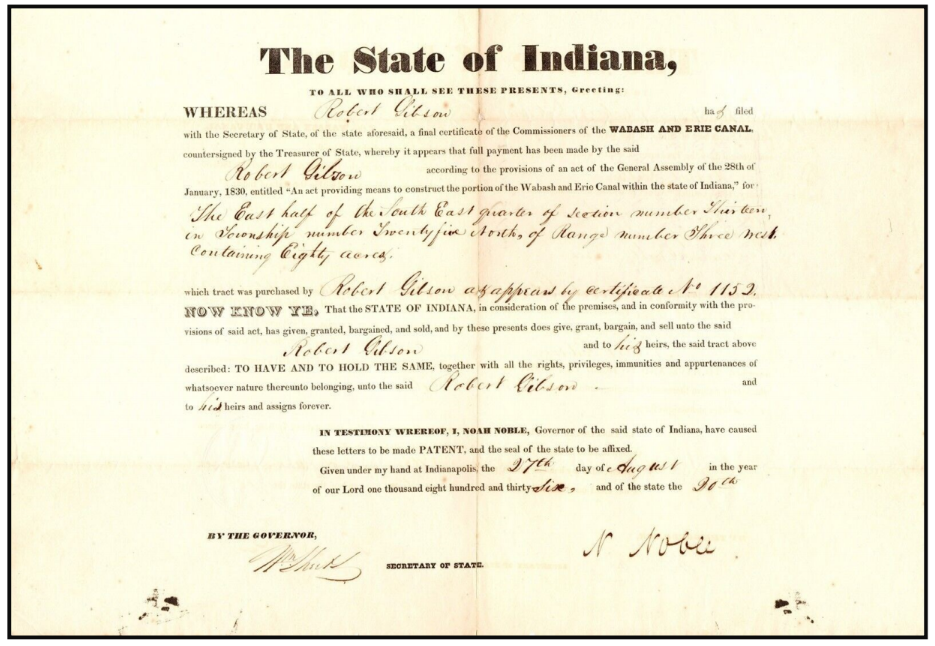

Canal Items On E-Bay

The following canal items were found on E-bay by Neil Sowards, CSI member from Ft. Wayne, Indiana.

The above document is in regard to the canal commissioners selling land to an individual.

The State of Indiana,

TO ALL WHO SHALL SEE THESE PRESENTS, Greeting:

WHEREAS Robert Gibson has filed with the Secretary of State aforesaid, a final certificate of the commissioners of the WABASH AND ERIE CANAL, counter signed by the Treasurer of State, whereby it appears that full payment has been made by the said Robert Gibson according to the provisions of an act by the General Assembly of the 28th of January 1830, entitled “An Act providing means to construct the portion of the Wabash and Erie Canal within the state of Indiana” for the East half of the South East quarter of section number Thirteen, on Township number 25 North of Range number Three West containing 80 acres which tract was purchased by Robert Gibson as appears by certificate number 1152.

NOW KNOW YE, that the State of Indiana in consideration of the premises, and in conformity with the provisions of said act, has given, granted, bargained, and sold, and by these presents does give, grant, bargain, and sell unto the said Robert Gibson and to his heirs, the said tract above described: TO HAVE AND TO HOLD THE SAME, together with all the rights, privileges, immunities and appurtenances of whatsoever nature thereunto belonging, unto the said Robert Gibson and to his heirs and assigns forever.

IN TESTIMONY WHEREOF, I, NOAH NOBLE, Governor of the said state of Indiana, have caused these letters to be made PATENT, and the seal of the state of be affixed. Given under my hand at Indianapolis, the 27th day of August in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and thirty-six, and of the state the 30th. (?)

By the Governor N Noble

Wm Sheets (?) Secretary of State

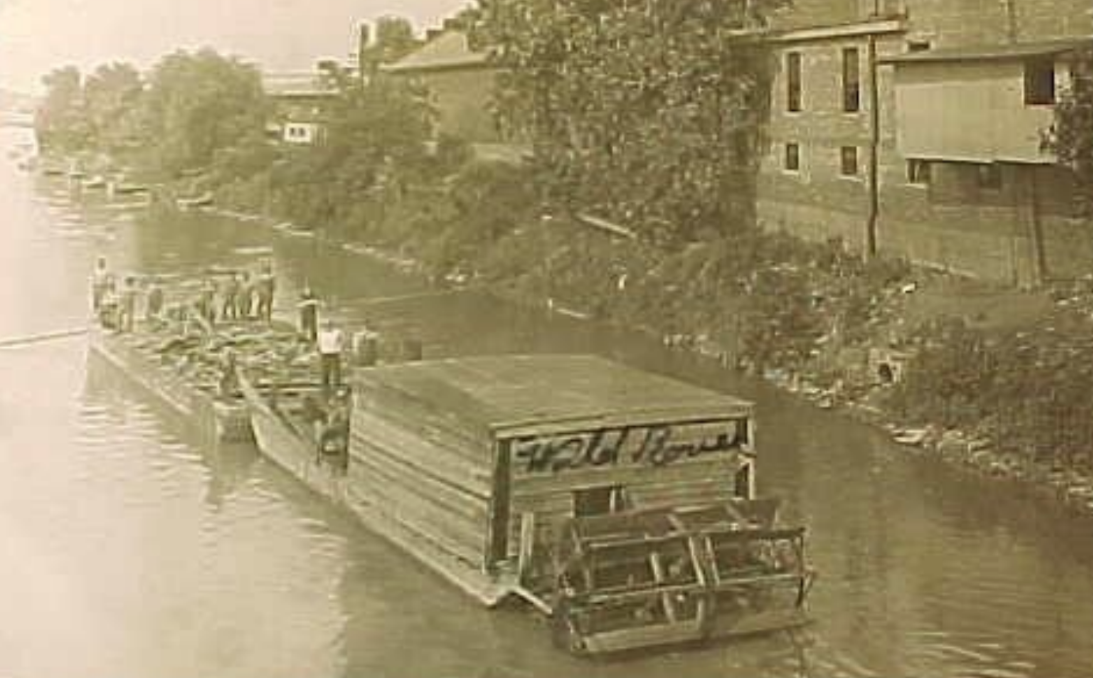

House Boat Photographer On The Canal

By Neil Sowards

Zanesville, Ohio. Neil Sowards says he has never seen anything like this.

Sometimes facts about the canal are learned from unexpected places. I saw a clipping that said, “Article from old scrapbook possibly published by Northwest News, Napoleon, Ohio around 1900”. The article was entitled “Henry County Court House—1865” and had a picture of said courthouse and the notation, “In this issue we produced a cut of the old court house taken from a photograph taken as near as we can recollect in 1865, …We traded a dozen eggs for it with a traveling photographer who floated up and down the raging canal on a house boat who went up and down the canal taking pictures for money or produce.

that may be purchased on the Canal Society of Ohio website.

The above photo shows a canal boat being used as the “Toledo Art Studio” that traveled up and down the Miami (Wabash) & Erie Canal northeast of Otsego, Ohio. The Maumee River is seen in the background.

The Muleskinners’ Language

By Neil Sowards

In my old age, memories of past stories come to the surface. Some seem worth passing on. About 1965 I was working as an assistant minister in Garfield Heights, Ohio. When the minister was on vacation, it was my job to visit members in an old folk’s home. One of our members told me this story.

As a child, she lived in Cincinnati, Ohio on one of the steep streets that led from the city beside the river up to the bluff. Steamboats bought goods to the city and they were loaded on freight wagons to be taken to places in southern Ohio.

The road was steep and the horses had trouble pulling the wagon up the steep grade. However enterprising men with teams of mules made a living hitching on to the front of their wagons and helping them to the top of the grade. Once at the top the wagon’s regular team could pull the wagon on the relatively level road.

Victoria lived on one of these steep streets and played in the front yard. She heard the muleskinners urging their mule to work harder with their colorful language.

One time she went with her mother down to Cincinnati to go shopping. She was dressed as a cute Victorian child complete with parasol, bonnet, and fancy clothing. When they were finished, they went to a trolley stop to catch a trolley home. There was an open basement window next to the sidewalk.

A Chinese man was working just a few feet away from her. He made a face and stuck out his tongue at her. She took this to be an insult and let go with a lot of words she had learned from the muleskinners describing him and his mother in their colorful language. Suddenly the crowd at the trolley stop became very quiet with every one looking at Victoria and her mother.

Everyone was opened mouth in shock!

Thereafter Victoria was never allowed to play in their front yard. She was confined to the back yard where she could not hear the muleskinners!

Memorials Honoring Steve Simerman

The Canal Society of Indiana has received memorials honoring Steve Simerman, whose obituary was in the March issue of The Tumble. These funds will be used toward the CSI signage program and educational programs.

| Carl & Barbara Bauer | Ft. Wayne | Barbara Klaehn | Ft. Wayne |

| Pamela & Wayne Bultemeier | Hoagland | Phyllis Mattheis | Cambridge City |

| Tom & Linda Castaldi | Ft. Wayne | Carol Roth | Ft. Wayne |

| Jane Clayton | Ft. Wayne | Bob & Carolyn Schmidt | Ft. Wayne |

| Joan Garman | Leo | Simerman | (from memorial box at funeral home) |

| Don & Betty Haack | Ft. Wayne | Quentin & Kim Thompson | Ft. Wayne |

| Virginia Hedges | Monroeville | Sandra & James Trumbower | Ossian |

| Sue Jesse | Ft. Wayne | Cynthia & Michael Waddell | Fishers |

Wabash-Erie Canal Walk & Talk

Written By: Preston Richardt / Photographs By: Sam & Jo Ligget

On April 6th, 2024, CSI Director Preston Richardt (Gibson Co.) led a walk & talk on the Wabash and Erie Canal around the Patoka River Aqueduct. This program was a joint venture with the Canal Society of Indiana and the Friends of Patoka River National Wildlife Refuge which Preston has been affiliated with for approximately 13 years.

The program began at the town of Dongola within the bed of the Wabash and Erie Canal. A short history of the canals was presented to the group explaining how canal fever spread across the nation in the 1820s and Indiana’s response to that fever. He explained how this section of the Wabash and Erie was originally part of the Central Canal then the change in names after the canal construction was given to private entities for completion. Additionally, he explained how the state and the country were in the midst of a depression starting in the year of 1838/39 due to the collapse of the tobacco market and the fact under a Presidential policy of Andrew Jackson United States money was no longer backed by a central bank.

After this short history, the group proceeded down the towpath of the canal into the woods where the prism becomes well defined. As the group walked Preston discussed the engineering and construction of the canal pointing out how high the earthworks in this section of canal tower above the flood plain of the Patoka River. He also explained the dredging of the river in the 1920’s that caused the river to be moved approximately ¼ mile north of the old channel and the old channel was renamed South Fork of the Patoka River after the old channel and the south Fork were merged as part of the dredging process.

Preston pointed out little details along the path such as the chat that was placed on the towpath to help protect it from excessive wear. He explained notches in the berm side of the canal that exist today that were cut to drain the canal in this area.

Upon reaching the aqueduct location, Preston had a diorama of the aqueduct that once spanned the valley and its associated river, in doing this he did not have to have everyone imagine what it looked like, but they could see the engineering for themselves. Additionally, Gary Siebert (CSI member from Gibson County) provided further information about the soil type in the area particularly the Hosmer Clay found just a few inches below the current topsoil and how it was the type of clay you wanted to line the canal with to hold water.

As the tour made its way back to the ghost town of Dongola, Mr. Richardt regaled the group with stories that were recorded to have happened in the area while the canal was being built and during its operation. The group paused to allow those who wished to go to the berm side of the canal to peer down the steep earthworks at the river some 30 feet below.

Upon reaching Dongola, Preston explained how the town was laid out in 1853 and explained where the warehouses were located as well as the basin. The town was the location of the last towing path change bridge and Mr. Richardt explained where it was located and how it works, explaining that it was a blend of our modern interstate interchange. He further explained the importance of the road that still runs through the area and how it was the original state road dating back to the early 1820s.

Other Canal Society members present were Sam and Jo Ligget, who brought their grandson with them. In all 27 people made the tour and all seemed to have enjoyed it. I want to thank the Patoka River National Wildlife management and the Friends of Patoka River NWR for their support and help in getting the path in good condition for the event.

CSI Fall Tour Announcement