- Watering the Wabash & Erie Canal

- Lewis Cass

- Canal Notes No. 14: Cap’t Asa

- Speakers Bureau – Ft. Wayne

- CSI Signs Up For Silver Creek Culvert And Lock # 11

- Burndt Finds/Questions Old Article About Bell In Canal

- Whitewater Canal Symposium: A Fun Learning Experience

- Canal Society of Indiana Minutes of Spring 2024 Annual Meeting

- Twists & Turns of Change

- Canal Mania

- 2024 Fall Tour Announcement

Watering the Wabash & Erie Canal

By Robert Schmidt

The initial water supply for the Wabash & Erie canal began at the dam on the St Joseph River 6 1⁄2 miles north of Fort Wayne, Indiana. Water from the St. Joseph Feeder at this summit level flowed both east 47 miles to Defiance, Ohio and west 27 miles to the Forks of the Wabash at Huntington, Indiana. To the east, the water from the St. Joseph River was supplemented by the 2,500 acre Six-Mile Reservoir near Antwerp, Ohio and later after 1845 by the Miami & Erie Canal at Junction, Ohio.

Following the canal route west of Fort Wayne, the Wabash River flows generally through a narrow valley, so that the river could be dammed at Huntington, Lagro, Peru and Pittsburgh. South of Lafayette the Wabash begins to widen and south of Terre Haute the flood plain is very broad and always subjected to flooding. The canal engineers decided to abandon the Wabash River water sources and instead utilize the larger creeks that fed into the Wabash. Although at this point, the Wabash & Erie no longer used the Wabash River as a water source, the canal still followed the river within a few miles just east of it.

There were two methods used to keep the canal water in the channel at the required minimum depth of 4 feet. The first method was to dam a creek or river, keeping the top of the dam at the height required to maintain the 4-foot level in the canal that entered into the dam’s pooled waters from both sides of the canal. This allowed the canal boats to enter what was called a slackwater pool. Here at the “slackwater” with only a slight current over the lip of the dam, a canal boat could be poled across the pool. This of course could be a disastrous crossing at times of flooding. This type of crossing often was just a straight-line crossing but sometimes the crossing pool was several miles long. The river slackwater at Pittsburgh (3 miles) and at Newberry (4 miles) are examples of slackwater at river crossings. This type of crossing really didn’t add a lot of water volume to the canal but just maintained the required 4-foot depth. Examples of creek crossings were at Deer Creek (Carroll Co,), Wildcat Creek (Tippecanoe Co.) and Coal Creek (Parke Co.) Each of these was about 70 yards across the slackwater pool.

The second method to feed the canal was to move to a higher elevation up a creek and construct a dam with a guard lock or gate mechanism to introduce additional water via this feeder directly under hydraulic pressure into the main canal channel, adding water volume. The feeder would enter the main channel just below the last lock on the lower end. In the 84 miles from Lafayette to Terre Haute there were 4 of this type of feeder: Wea Creek (Tippecanoe Co.), Young’s Creek and Shawnee Creek ( Fountain Co.), and Sugar Creek (Parke Co.). The longest of these feeders was the Sugar Creek feeder, 3 miles long. Remember as the W&E channel or prism proceeded in a southerly direction toward Terre Haute the elevation continued to fall and the water flowed naturally from the higher to the lower level.

Watering the Canal from Terre Haute to Evansville

In 1847 the canal engineers at Terre Haute had a choice. Either stay close to the Wabash and risk flooding the canal or move it to a higher elevation. The Wabash River at this point meanders 200 miles in a very broad flood plain continuing until it enters the Ohio River at the southwest tip of Posey County. Even today to reach the river there are few roads or means for any public access except through the farmland. The farms are productive when not flooded, but there are still many swamps and bayous and practically no towns.

The choice for the engineers was predetermined by the earlier canal plans of the state of Indiana. The original plan created in the 1836 Mammoth Improvement Bill was to build the Wabash & Erie to Terre Haute. The Central Canal was planned to proceed from Peru thru Indianapolis to Point Commerce (Worthington) and then to Evansville. The route had been engineered and 20 miles of canal completed out of Evansville that were just waiting to be connected. A 42-mile Cross-Cut canal from Terre Haute to Worthington had also been engineered in 1837 and some structures completed. However, work ceased when the state ran into financial difficulties in 1839. The Cross-Cut Canal was originally designed to link the Wabash & Erie Canal with the Central Canal.

The Cross-Cut Canal was planned to bring the waters from the summit in Clay County into Terre Haute. This would merge the waters at the nadir level, where water from the north met the waters from the south. At this nadir (lowest) level water would be directed into the Wabash River in downtown Terre Haute. In 2022 our Canal Society placed a historical sign at that significant point.

On July 2, 1845, Governor James Whitcomb requested that a survey be completed from Terre Haute to Evansville. His letter was addressed to Robert Henry Fauntleroy, a famous Civil Engineer and surveyor from New Harmony. Fauntleroy then proceeded to hire William J. Ball, Samuel C. Bradford and Michael Riley to do the actual physical surveying. Ball, who was the Principal Assistant, had married Julia Creighton in November 1842 and moved to Terre Haute. Julia was the sister of Susan Creighton, the wife of Jesse L. Williams, the Chief Engineer of the Wabash & Erie Canal.

The 1845 Documentary Journal to the General Assembly of Indiana.

INDIANAPOLIS, December 13, 1845.

His Excellency JAMES WHITCOMB,

Governor of the State of Indiana:

Having complied with your letter of July 2, 1845, requesting me to proceed in the business of ascertaining and defining the route and location of the Wabash and Erie Canal, as extended from Terre Haute to Evansville,” &c., I beg leave to submit to you the following report:

With a view to the speedy accomplishment of the object before me, it was considered important to engage the services of Engineers who had previously been employed upon the route of the canal, and whose professional skill and knowledge of the country traversed by the canal, would tend to expedite the surveys about to be commenced. Accordingly, applications were made to William J. Ball, and Samuel C. Bradford, and their services obtained. Mr. Ball was instructed to organize a suitable party and proceed to make the necessary surveys over the located portion of the canal extending from Terre Haute to the junction of the main line and feeder near Rawley’s mill on Eel river; and on the accomplishment of this, to organize a full locating party and commence examinations for reservoirs in the valley of Eel river, with a view to determining the principles which should govern the location of the canal from the junction of the main line and feeder to the most suitable point in the valley of White river, at which to form the connection with the southern portion of the (Central) Canal. Mr. Bradford was instructed to organize a party, and to make the necessary surveys from Evansville, to the neighborhood of Point Commerce, situated at the mouth of Eel river; embracing that portion of the Central Canal, which had been previously located by S. Holman and C. G. Voorhies. Soon after these parties were in the field, I joined Mr. Ball, then encamped on Eel river, and remained with the party until the completion of the survey.

Before entering upon the business of ascertaining and defining the route and location of that part of the (Cross-Cut) Canal which extends from the neighborhood of Rawley’s mill down the valley of Eel river, to its junction with the Central Canal, it was necessary to settle a question of the highest importance; that is, in what manner the canal should be supplied with water.

The report of the principal Engineer to the State Board of Internal Improvements of December 5, 1837, shows that two lines had been surveyed from Rawley’s mill down the valley of Eel river, one on each side of the stream and intersection near its mouth with the Central Canal; and that, either of these lines would depend for a supply of water, partly upon Eel river, by means of a dam to be built at Rawley’s mill, and partly upon White river through the Central Canal south of the intersection; and, with the view of rendering the water of White river available as far up the Cross-cut Canal as possible, the two canals were brought together upon as high a level as the character of the route would allow. From this, it will be plainly perceived, that, to adopt either of the above lines would involve the necessity of a dam on White river, and also a feeder including an aqueduct across either Eel or White river. This mode of supplying the canal with water would evidently involve a heavy expense, not necessary to be incurred, unless either, it were intended to complete the Central Canal throughout, or no other plan could be devised less expensive in its construction. Another objection to this plan is, that the natural flow of Eel river is not sufficient to supply the canal from the summit to Terre Haute, and also water for lockage in the opposite direction. This fact has been ascertained by Mr. Ball, as he informs me, since the surveys above alluded to were made. Under all these circumstances, and especially since provision for an additional supply of water to the summit level was necessary, which could only be effect by means of one or more reservoirs, it was thought advisable to examine for reservoirs in the valley of Eel river, so situated that at least one should command the summit level, and sufficiently capacious to satisfy all the requirements of the canal in each direction from the summit, and not be depend upon White river for any part of the supply north and west of the Newberry feeder.

Upon the suggestion of Mr. Ball, the valley of Splunge creek was examined instrumentally as a suitable site for a reservoir. This creek discharges into Eel river at Rawley’s mill, about one and three quarter miles below the junction of the main line and feeder, and admits of a reservoir being constructed in its valley, at a moderate cost, of eight feet available depth of water; occupying when filled to its maximum depth about 3900 acres of ground, and when drawn down to its minimum depth, about 1900 acres. The ground occupied is, for the most part, a low wet prairie, subject to inundation during wet seasons, by the high waters of Eel river, and of but little value as farming land. The soil consists of clay a character well adapted to the retention of water. This reservoir will be formed by one of the banks of the canal, increased in its dimensions to insure stability. In estimating the cost, the height of the bank was assumed at four feet above the surface of the reservoir when full, and the width twenty feet, with a course of sheet piling built up in the centre from the level of the water in the canal to that of the water in the reservoir when full. This bank will be one mile and fifty five chains in length, averaging about 9½ feet in height, and will be formed chiefly with the excavations from the canal. The bank when built will be used as a public highway, which will have a tendency to settle it and prevent the occurrence of a breach. The reservoir will be filled partly by the drainage of the county immediately surrounding it, and partly by the flood water of Eel river, discharged into it by means of the present dam and feeder. In surveying this reservoir, the level of the surface when filled, was assumed at five feet below the bottom of the feeder or canal on the summit level, from which it will be seen that a greater depth than eight feet may be given to it, if thought necessary. It will contain when filled to the depth of eight feet very nearly 1,000,000,000 cubic feet of water. If we deduct from this quantity one third of the whole, as loss by evaporation and filtration, there will remain 666,666,666 cubic feet, which is equivalent to a constant supply of 3794 cubic feet per minute for four months. The length of canal to be fed by this reservoir is 34 miles; hence, the above supply is equal to 111 cubic feet per minute for each mile of the canal through a period of four months, which quantity is greater than the probable demand for purposes of navigation. The extent of county draining into this reservoir, embraces the entire valley of Eel river north of the feeder dam, amounting to not less than 20 congressional townships, or 720 square miles, the annual drainage of which is sufficient to fill a reservoir of at least eight times the capacity of the one under consideration, and therefore is so largely in excess of what is required, that I deem it unnecessary to enter upon any further investigation in regard to the certainty of supply this reservoir.

Note: As stated above, Governor Whitcomb’s letter was to locate the canal from Terre Haute to Evansville. The route from the summit in Clay County to Terre Haute had been engineered in 1837 with 6 locks totaling a 60-foot descent. Locks 41 & 42 in the city brought the total lockage to 79 feet from the summit.

Inside Terre Haute City limits = 19.2 feet

Lock 41 & 42 = 19.2 Ft. – Shared a common gate

Outside of Terre Haute to the Summit = 60 feet

Lock 43 & 44 = each 8½ Ft. / Lock 45 = 9 Ft.

Lock 46 8½ Ft. / Lock 47 = 8½ Ft. / Lock 48 = 8 Ft. / Lock 49 = 9 Ft.

In 1823 at Rawley’s mill, a small dam was constructed across Splunge Creek where it entered Eel River. The 1837 plan was to build 2 feeders, one across the Eel River at Rawley’s Mill and another on the White River in southern Greene County on the White River. Mr. Ball felt that a reservoir on Splunge Creek, fed from a feeder and dam higher up the Eel River, would supply at least 8 times as much water as the original plan. Ball pointed out that the normal flow of Eel River alone would not supply enough water to flow both north to Terre Haute and to the south as well.

A reservoir of 3,900 acres with a 8-foot depth would accumulate water that would allow more of the water from the Eel River Feeder to be directed to the north increasing the potential for mills in Terre Haute. The dam across the valley of Splunge Creek would be about a 1½ miles long 20 feet wide at the top with sheet pilings in the center and a height of 9½ feet. The canal would be constructed along this embankment with a roadway on top of the earthen dam. Water to fill the reservoir would come from two sources:

The natural drainage of 720 square miles into Splunge Creek

The excess water coming from the Eel River Feeder and dam 5 1/2 miles to the East

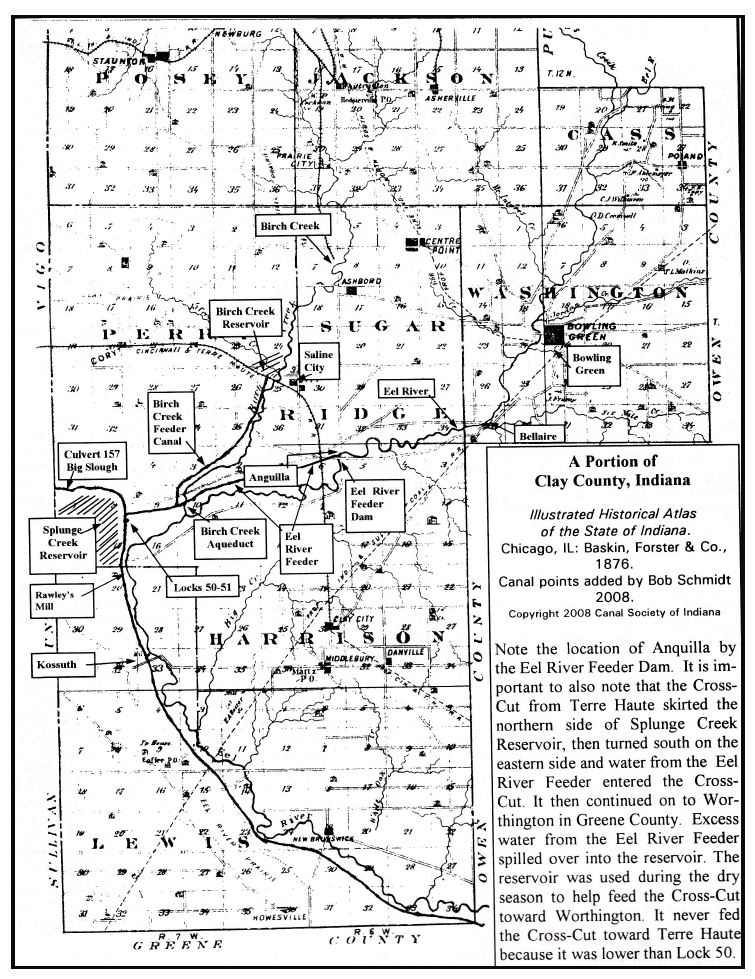

The Eel River Feeder

This feeder for the Cross-Cut Canal was the most complicated system on any of Indiana’s canals. Refer to the above map as you read this interpretation of how the system worked. A dam, 264 feet long and 16 ½ feet high was built on the Eel River at the location of the future plotted village of Anguilla (Eel). The Feeder from the dam and guard lock to the main canal was 5½-miles-long. The Feeder dam backed up water for 12 miles up the river in a slackwater to Bowling Green, the county seat at that time. The Feeder canal to the reservoir carried water into the main canal 20 miles to Terre Haute, then 22 miles to Point Commerce (Worthington) and still another 12 miles to the White River near Newberry, making a total distance of the 54 miles. Excess water in the feeder during the spring wet months was directed into the Splunge Creek Reservoir. They created the reservoir, which gathered water from the normal flow of the creek and stored the excess water from Eel River, by damming Splunge Creek. The reservoir water was then released into the canal to flow south, but due to the reservoir’s elevation it could not flow north.

As the Eel River Feeder proceeded west from the river dam it had to cross Birch Creek at a right angle. Initially the engineers did not want to introduce the creek’s waters into the Feeder so they built an open trunk aqueduct of 3 spans of 27 feet each for a total span of 81 feet. When the feeder water reached its junction at the Splunge Creek Reservoir it could follow 3 different paths:

The first was a sharp right turn toward Terre Haute along the summit. At the far end of that summit about 8 miles away was Lock No. 49, which had a tumble allowing excess water to bypass the lock and proceed toward Terre Haute.

The second was for water to flow directly into the Reservoir when the two iron 5½-foot roller gates were lifted.

The third was for the water to pass into Lock 50 and then shortly into Lock 51 when there was boat traffic. Both of these locks had an 8-foot lift. This meant that there was a 16-foot drop from the Feeder canal to the lower level of the main canal that ran along the foot of Splunge Creek Reservoir. These locks did not need a tumble since any excess water from the Feeder could be directed into the reservoir or toward Lock 49 and its tumble. The main function of these 2 locks was to raise and lower boat traffic. If required, all of these locks’ gate paddles could be put into the open position for some water to flow through and into the main channel to the south. Most of the water in the main channel flowing to the south would pass through the 4 iron sliding gates at the south end of the Reservoir. Some of the released water would backflow toward Lock 51. Remember there were no other water sources before the canal reached the White River slackwater at Newberry. There were no slackwater crossings along the route, but there were several waste weirs to allow excess water from the reservoir to flow out of the canal.

Although this plan sounds fine, there was still a shortage of water for the canal south toward Worthington. In 1853 an additional 1000-acre reservoir was created by damming Birch Creek. The 4-mile Feeder from this reservoir fed directly into the existing Eel River Feeder entering just west of the old aqueduct over the same Birch Creek but further down. Disease around both reservoirs was the primary reason given for vigilante actions against the structures from 1854-55.

How did the towpath function at the summit level and along the feeder? From Terre Haute and Riley the tow animals were on the north and east side of the canal. A half mile after passing Lock 49 there was a towpath bridge that allowed the tow animals proceeding south to cross over to the west side of the canal. About 7 miles later, they crossed over the embankment where the iron gates of the reservoir weir were located and then proceeded down the embankment to a bridge at the lower end of Lock No. 50. There the tow animals crossed to the east side of the main canal. They remained on that east side all the way to the White River slackwater at Newberry. Boats heading for Bowling Green would follow the towpath along the south side of the Feeder to the dam. Passing through the guard lock and following the Eel River to Bowling Green was probably done by pushing poles along the bottom of the river to move the boat. Boats coming down river from Bowling Green toward the dam had the benefit of a slight current.

Watering the Wabash & Erie Canal

If we look at the Wabash & Erie Canal water supply throughout Indiana, we find that the northern portion of the canal was well supplied by the St Joseph River and 4 dams on the Wabash River. Below Lafayette to Terre Haute there were 4 feeders built on creeks. The Cross-Cut Canal was fed northward by the Eel River Feeder, to the south by that same feeder, and also by the Splunge Creek Reservoir. From Newberry to Evansville there were 2 slackwater crossings (Newberry & Slinkard’s Creek), 1 reservoir on Pigeon Creek at Port Gibson and 1 dam on Pigeon Creek in Warrick County. If the water level in the White River at Newberry dam fell below its lip, the water level in the canal could not be maintained at the 4-foot depth. This happened frequently and the canal was inoperative in the summer months during the 1850’s just when it was needed to transport goods and crops.

There were no other feeders south of Newberry. The Splunge Creek Reservoir only watered the Wabash Canal into the White River at Newberry. Perhaps the Engineers figured the traffic on the lower 95 miles from Newberry to Evansville did not warrant the expense of building more infrastructure. Also remember that at this time after 1847 the Wabash & Erie Canal was being operated by the Trust, not the state of Indiana.

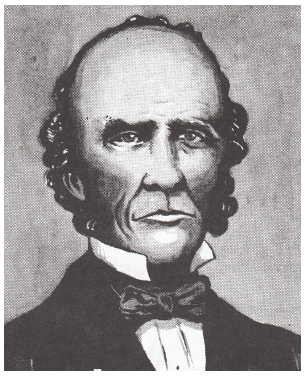

Lewis Cass

By Carolyn Schmidt

(October 9, 1782-June 17, 1866)

Find-A-Grave 2256

Lewis Cass was born in Exeter, New Hampshire on October 9, 1782 to early Puritan settlers of New England. His father, a blacksmith, was a commissioned officer in the Revolutionary Army participating in the battles of Bunker Hill, Saratoga, Trenton, Princeton, Monmouth and Germantown. Lewis was the eldest of five children—three boys and two girls.

Lewis received his early education entering Exeter Academy in New Hampshire at age 10. At seventeen, he taught at a local school in Wilmington, Delaware where his father was stationed in the army. When his father resigned Lewis accompanied him by hiking over the Alleghany Mountains seeking his future in the “Great West.”

In 1799 the family settled near Marietta, Ohio. Lewis began the study of law at Marietta, dividing his time between reading the law and helping his father clear the family land, build a log cabin and set out a crop. At the age of twenty he was admitted to the bar, the first lawyer to be licensed under the new Ohio constitution of November 1802. He settled in Zanesville, Ohio and rode a circuit of a hundred miles between county seats creating a practice. By the time he was twenty-one he was making a comfortable living, by twenty-two he was elected prosecuting attorney for his county and by twenty-four he was elected to Ohio’s legislature, being the youngest member of the legislature. Ohio had recently been admitted to the Union in 1803. There he proposed a bill which started the movement that led to the defeat of the conspiracy of Aaron Burr. President Thomas Jefferson appointed him Marshal of Ohio, a position he held from 1807 to the outbreak of the War of 1812.

In late 1811, Indians attacked American camps on the Wabash trying to recover lands ceded to the U. S. Government. Troops from Kentucky and Ohio went to the rescue. Cass was one of the first to rendezvous at Dayton. There he was elected Colonel of the Third Regiment of Ohio Volunteers by acclamation. In June of 1812, Cass marched his regiment two hundred miles through the wilderness to Detroit in anticipation of a war with England, which was declared at about that time. He authored a proclamation and urged an immediate invasion of Canada. He was the first armed American to land on the shore of Canada. His small detachment of troops fought and won the first battle.

General William Hull did not follow up on Cass’s early successes and ordered Cass to give his sword to a British officer. Colonel Cass disobeyed and broke the sword over his knee. His command was included in the surrender of Detroit. However, Cass was paroled and immediately went to Washington City to report the causes of the disaster, was appointed a Colonel in the Regular Army, fought under General William Henry Harrison, and was soon promoted to Brigadier-General.

Cass then went back to the frontier and joined the army to recover Michigan. Commodore Perry had swept the Lewis Cass enemy’s fleet from Lake Eire, which opened the way for General Harrison, under whom Cass served as aide-de-camp. Cass won distinction at the Battle of the Thames. This victory restored the Territory and made Cass the military governor of Michigan.

In October 1813, President James Madison appointed Cass the civil governor of the Michigan Territory. To his ordinary duties as chief magistrate of the civilized community were added the management of Indian relations with numerous and powerful tribes of the Great Lakes region. Cass began negotiations with Indian tribes and the Federal Government in 1815. This led to a great circular exploration by canoe and horseback in 1820 to ascertain the resources of the region and cultivate friendly relations with the Indians. It included the Lake Huron shore and the Sault, the Lake Superior country, the area around the head waters of the Mississippi, and the future site of Chicago. At the time Michigan Territory included what is now Wisconsin, Minnesota and Iowa. Cass was then appointed the 2nd Governor of the Territory following General William Hull.

Cass negotiated twenty-one treaties with the Indian tribes of the Northwest, which preserved law and order and advanced the Territory in population and prosperity. During his 1813-1831 time of service as Territory Governor he also improved education and transportation, created a judicial system, and promoted statehood for Michigan. His accomplishments are described in the book They Also Ran: “He had started in 1814 with a wrecked, war-torn, poverty-stricken wilderness. Within fifteen years he had attracted thirty thousand settlers; he had quieted the Indians, made them friendly, kept the ever hostile British off the neck of the young community; he had built roads, was exporting flour to the east, and prepared an American commonwealth to become a full-blown state. It was an accomplishment of herculean proportions brought about with infinite patience, boldness, tack, industry and skill. Lewis Cass had become known as one of the world’s great empire builders—and he had accomplished it all before he was forty.”

In 1826 Cass, along with John Tipton and Indiana Governor James Ray, was one of three commissioners at the Treaty of Paradise Spring in Wabash, Indiana that acquired the lands for the Wabash and Erie Canal. In 1828 Cass County in Indiana was named in his honor.

In 1831 President Andrew Jackson appointed Cass, age 49, to his cabinet as Secretary of War. He served in this position for five years.

In 1836 Cass was appointed Minister to France, where he gained the respect and admiration of Europe through his service to the United States by defeating the attempt of Great Britain to gain by treaty the right of searching our vessels at sea. Cass requested he be recalled in 1842 in protest over the Webster-Ashburton Treaty and returned to the United States. This treaty defined the border between the US and British Canada.

By 1843 the Wabash & Erie Canal had been completed from Lafayette, Indiana to Toledo, Ohio and a committee of arrangements for a Grand Canal Celebration was set up. As a person of national prominence and one who was seeking to run on the Democratic ticket for President of the United States, they decided to ask sixty-year-old Lewis Cass to speak that day. The local Fort Wayne Sentinel carried the following articles:

CELEBRATION. It is in contemplation by the citizens of the vast region of country bordering along the valley of the Maumee, to celebrate in a suitable manner, the completion of the Wabash and Erie Canal, at Fort Wayne, in the state of Indiana, on the 4th of July next, and it is intended we learn, to solicit our distinguished fellow citizen, General LEWIS CASS to deliver an oration on the occasion. No individual could be selected, who would do up such an under taking in better style – or whose presence would be more cordially received by the hardy Hoosiers and Buckeyes who will doubtless be there congregated in vast multitudes. Long identified with the great interest of the West, and personally known to thousands of its early inhabitants, – although separated from them for a time in the discharge of important public duties, – we trust he will not fail to accept the invitation; and it is further hoped that such of the citizens of Michigan to have leisure and can afford it will likewise participate in the contemplated celebration got up by the hardy border settlers of our sister states.

Detroit Constitutional Democrat

Our friends at Detroit are rather in advance of the mails. The committee has not yet selected an orator. Gen. Cass has been invited to attend the celebration, and of course would be expected to address the assemblage; he may perhaps be selected as the orator of the day, but the choice is not yet made. The selection of Gen. Cass would give general satisfaction.

CANAL CELEBRATION. The approaching celebration of the completion of our canal, will, we expect, be numerously attended. We hear, verbally that the inhabitants of every town along the line feel the liveliest interest and are preparing to participate. The Toledo Guards, and the companies in Lafayette, and probably other places, will be here. We have no doubt there will be as many come as all the boats on the canal can accommodate.

The committee of arrangements have selected a grove on the farm of Col. Thomas Swinney as the place at which the exercises of the day will be held. It is a beautiful site, exactly suited for the occasion, large enough to accommodate the vast crowd who will assemble, and sufficiently shaded from the sun to be pleasant and agreeable.

June 17, 1843

CANAL CELEBRATION. Gen. Cass has been invited to deliver the oration at the approaching Canal Celebration. WE have not yet heard whether any of the other distinguished gentlemen invited will attend; but we hear from every quarter that the number coming will greatly exceed all previous calculations. The contribution toward defraying the expense have been most liberal, all appear animated with the same spirit, and desirous of contributing according to their means, in celebrating the consummation of the hopes which have so long sustained them amid the difficulties which have surrounded them, but which are now surmounted; and however numerous our guests may be, there will be enough provided for all and to spare. Several volunteer companies from Lafayette, Logansport, Toledo, &c. will aid in the celebration.

We understand a large company of warriors of the Miami tribe of Indians will be here at the celebration, and will perform their war dance. This will be a most interesting feature in the celebration., To see these noble looking men, the last relic of the once numerous powerful Miami’s, on such an occasion, and on the spot, once their strong hold, and where the redmen were more numerous that the whites are now – will be an affecting spectacle, and one will calculated to impress their memory upon the minds of those who witness it, long after they have been swept away by the resistless tide of immigration. The Miami village at this point before its destruction by Wayne, we are informed, contained a population more numerous than our city does at present. Now their lands are in the hands of strangers, and they themselves will be a spectacle to interest those assembled on the very spot where in former times they bore undisputed sway. In a few short months this tribe will bid a final adieu to the land of their birth and the graves of their fathers, and remove beyond the Mississippi.

June 24, 1843

Gen. Cass has accepted the appointment of Orator of the Day at our approaching Canal Celebration.

The Grand Canal Celebration was a huge success. It is estimated that 8,000-10,000 individuals attended the event. Gen. Lewis Cass gave a long stirring address that was punctuated by the firing of a cannon and cheers from the audience. In his speech he said, “We have come to witness the union of the Lakes and the Mississippi and to survey one of the noblest works of man in the improvement of that great highway of nature, extending from New York to New Orleans, whose full moral and physical effects it would be vain to seek or even to conjecture.

“…This work …..binds together this great confederate republic. Providence has given us union and many motives to preserve it.

“Today a new work is born—a work of peace and not war. We are celebrating the triumph of art and not of arms. Centuries hence, we may hope that the river you have made will still flow both east and west; that it will bear upon its bosom the riches of a prosperous people, that our descendants will come to keep the day which we have come to mark; and that, as it returns, they will remember the exertions of their ancestors, while they gather the harvest.”

In 1844 Lewis Cass was a major Democratic candidate for the presidential nomination. Unfortunately he lost the nomination to dark-horse James K. Polk.

In 1845 Cass was elected to the United States Senate from Michigan. During his first term 1845-1848 he supported the Mexican War and westward expansion. At the Democratic national convention in Baltimore in May 1848, Cass was the clear favorite of more of the delegates and won the nomination of the fourth ballot. He resigned this senate position in 1848 after his nomination for President. He campaigned this time warning against federal interference with the practice of slavery. At the election he lost to the Whig candidate and Mexican War hero, General Zachary Taylor.

In 1849 Cass was re-elected to the Senate to fulfill the unexpired portion of his original term of six years. He joined Henry Clay in putting together the Compromise of 1850. He was re-elected to the senate in 1851 serving until 1857 when President James Buchanan appointed him Secretary State.

In 1860 he resigned as Secretary of State because he did not agree with the views and methods of Buchanan – especially his failure to deal more sternly with threats of rebellion in the South. Cass returned to Detroit feeble and broken in health, a seventy-eight-year old man. He was oppressed by the dangers which threatened the Government and, on April 25, 1861, he addressed a public meeting in Detroit about the need to preserve the Union. He lived long enough to see the Union preserved.

Lewis Cass died in Detroit on June 17, 1866 at age 83. He was laid to rest in Section A Lot 25 of Elmwood Cemetery, Wayne County, Detroit, Michigan.

Cass Family

Although much was written about the political life of Lewis Cass, little can be found about his family life. Ancestry.com and Find-A-Grave had the following information:

His father was Jonathan Cass. Mary Gillman Cass was his mother.

In 1806, at age 24, he married Elizabeth Spencer (B. September 27, 1788, D. March 31, 1858). Elizabeth was the daughter of Dr. Joseph Spencer, lived in Vienna, Wood County, (West) Virginia, and later moved to Detroit when Lewis became the Governor of Michigan Territory.

1788-1858

Lewis and Eliza had 4 children:

Lewis Cass – (B. ?, D. 1878)

Elizabeth Seldon Cass – (B. 1811, D. 1832)

Mary Sophia Cass Canfield – (B. 1812, D. 1882)

Matilda Frances Cass Ledyard – (B. 1818, D. 1898)

After the children were older and when Lewis was the Secretary of War (1832-1836) in President Jackson’s Cabinet, Elizabeth was a “Cabinet Lady” in Washington City. Later she went with him to Paris where he was U. S. Minister at the Court of France and they lived life in high style. She also accompanied him on his oriental travels. She preceded Lewis in death dying in Detroit on March 31, 1858 at age 70.

The Myth

About 66 years after the Grand Canal Celebration was held in Ft. Wayne, LeRoy Armstrong, a reporter for the Lafayette (Indiana) Journal put the following in his paper on September 25, 1899: “A local poet had written some grandiloguent lines and it was part of the ceremony that these verses should be read to the statesman as he disembarked…The gangplank was not accurately stayed, and while General Cass stood listening to the phrases he could not understand, the plank slipped and down went the thriftiest of trimmers. He came up moist but fervid and won Indiana to his presidential plans.”

This story has been passed down for years. Dr. George Clark, a professor emeritus at Hanover University and CSI member in 1993, questioned if Armstrong’s report was true since Cass was campaigning to be the Democratic nominee for President and reports would have undoubtedly made a big deal of such an event. Dr. Clark set out to disprove the report and wrote an article for the Indiana Historical Society’s magazine “Traces” Vol. 5, No. 2 Spring 1993. The seven page article shows how a statement such as this gets embellished as others report it. Clark said:

“There is simply no credible evidence that Lewis Cass ever fell into the Wabash and Erie Canal at Fort Wayne. Quite to the contrary, there is ample evidence that reporters of the celebration beheld no such dramatic event.”

Dr. George Clark, Hanover University

Dr. Clark said that,

“…one cannot overlook a possible political motive in the tale as well. Armstrong, from available evidence a Republican, clearly took inordinate delight in imagining the humiliation of a great Jeffersonian Democrat.” It enlivened his piece and “If it is not true, at least it is very well invented….Armstrong’s scenario provides such a dramatic metaphor for the fall of any erring politician, that his plausible fabrication has found a place in Hoosier Annals.”

Dr. George Clark, Hanover University

Lewis Cass was an ideal speaker for the Fort Wayne canal celebration due to his earlier treaty negotiations at Paradise Spring and his governorship of Michigan Territory. Cass was a great public servant for our country. He was certainly one of the most qualified candidates in domestic and foreign affairs to later run for the office of President. He had served in the Ohio Legislature, been Governor of Michigan Territory for 18 years, Secretary of War under President Jackson and Minister to France. In the democratic election process, popularity with the voting public is often more important than qualifications as recent elections have revealed. Zachery Taylor was a war hero and really had no background to be President. Unfortunately, the country never got to experience a President Cass.

Bibliography

Ancestry.com. Lewis Cass, Elizabeth Cass

Canal Celebrations In Old Fort Wayne. Staff of the Public Library of Fort Wayne and Allen County, 1953.

“Canal Celebration.” Fort Wayne Sentinel. 6-3-1843, 6-17-1843, 7-24, 1843.

Clark, George P. “The Dunking of General Cass: A Hoosier Myth” Traces Indiana Historical Society. Vo. 5 No.2 Spring 1993: 5-11.

DeGregorio, William A. The Complete Book Of U.S. Presidents From George Washington to Bill Clinton. New York: Wing Books, 1997 (Fifth Edition).

Find-A-Grave. Lewis Cass, Elizabeth Cass.

Fuller, George N. ed. Messages Ot The Governors Of Michigan: Vol. 1. Lansing, MI: The Michigan Historical Commission, 1925

Griswold, B. J. A Pictorial History Of Fort Wayne Indiana. Chicago, IL: Robert O. Law Company, 1917.

Poinsatte, Charles R. Fort Wayne During The Canal Era 1828-1855. Indiana Historical Bureau, 1969.

Stone, Irving They Also Ran: The Story Of The Men Who Were Defeated For The Presidency. Garden City, New York: Doubledaym, Doran and Company, Inc., 1944.

Canal Notes No. 14: Cap’t Asa

By Tom Castaldi

1797-1868

Hey kids, moms and dads! How would you like to take a ride with Cap’t Asa Fairfield on the Wabash & Erie Canal? Well, Cap’t Asa’s first passenger packet boat, The Indiana, departed from Ft. Wayne for a day long trip to Huntington on July 3, 1835. Unfortunately, we missed the boat.

Even after 189 years, as luck would have it, it’s possible to drive your car along the old canal right-of-way. West of Ft. Wayne on U. S., 24 beginning near the County line, the highway lies virtually on top of the canal all the way into Huntington, Indiana.

You’ll have to imagine you’re traveling 5 miles an hour instead of 50, but the landscape is similar and the stream are still there to be crossed. Road bridges have replaced the canal culverts over creeks whose names, Calf, McPherrens and Cow remain unchanged.

DICKEY LOCK marker reads: NEAR INTERURBAN STATION. LOCK ON OLD WABASH AND ERIE CANAL . PORTION ORIGINAL STONE WORK REMAINS. CANAL UNITED WATERS OF LAKE ERIE AND OHIO RIVER.

Drawing and map by Bob Rose, CSI member from Roanoke, IN in 1999

Photo by Bob Schmidt

At Roanoke a car may have to stop for a traffic light. Cap’t Asa had to steer his real live horse powered boat into Dickey Lock. Here The Indiana was lowered 9-feet taking about a minute for each receding foot of water. Then the big west-end lock gates were opened, and The Indiana floated onto the lower level of the canal, as the horses strained at the tow-line moving the packet ever westward.

After passing Port Mahon, Cap’t Asa’s boat could glide through an aqueduct over Bull Creek, but you’ll still be doing 50 or more miles-per-hour. Finally, Flint Creek was crossed and The Indiana docked at the upper lock known as Burks Lock. Celebrating the arrival of the first canal boat on that July 1835 day, a large and enthusiastic group of Ft. Wayne citizens were met by an equally enthusiastic Huntington crowd.

The old captain isn’t around today, yet he and others like him made sure the way was opened. The Indiana took all day to travel what we cover in just 30 minutes. Maybe we didn’t miss the boat after all.

Speakers Bureau – Ft. Wayne

On May 2, 2024 Bob and Carolyn Schmidt presented a program about Indiana’s canals highlighting the Wabash & Erie Canal to the Heritage Club in the home of Holly Beerman in Fort Wayne. The nine women present were from the Fort Wayne area and several had lived earlier in Ohio. Bob told the basic history of the canals, the importance of the Wabash & Erie, when its sections were completed, where the men who built it came from and the tools they used. Carolyn talked about how the canal and its structures were built and how they operated. Carolyn also took two canal boat models built by deceased member Bill Davis to show how narrow the boats were and explained that they had to fit within the lock chamber. The Scmidts also passed out information about where canal exhibits and canal boat rides could be seen. They were encouraged to join CSI. The program lasted from 1-3 p.m. as the ladies had many questions and things to relate of their canal experiences.

CSI Signs Up For Silver Creek Culvert And Lock # 11

Richard Ness has had the signs donated by CSI erected in his park along the Wabash River southwest of Huntington, Indiana where the Wabash & Erie Canal crossed Silver Creek via a stone arch culvert before being lowered to anther level by Lock #11 approximately 50 yards west of it. It can been seen at a distance from highway U.S. 24. The following pictures were taken by Bob Schmidt on May 17, 2024 showing the signs, Wabash River, and the culvert.

This culvert was originally built of timber but later replaced as a stone arch in the 1840s. The stone culvert was almost washed away during floods over the years. Without Richard Ness and his father, the previous owner of the property, these remains probably would have been lost. Richard removes the debris coming down the creek from the culvert’s northern portal, which is missing. He has created a lower area where high water will pass around it, and has paved over its top with a roadway. Huge boulders and other stone have been placed to protect it. He is planning on building an even higher overlook of the river and culvert from a nearby hill. We thank him for all his efforts to preserve this historic site and all the work he and his wife have done to beautify this spot with roses, other flowers, plants, trees, a swing and picnic area.

Note : Both portals are missing their facades and wingwalls.

Burndt Finds/Questions Old Article About Bell In Canal

Craig Burndt, CSI member from Fort Wayne, Indiana, found the following article published in the Ft. Wayne News Sentinel on July 4, 1939 and questions some of the reporting:

Note: this article is setup just as it appeared in the Ft. Wayne Sentinel on July 4, 1939. As you read this article start in the left column and finish at the bottom of the right.

Sixty-five years ago in September the “Fort Wayne,” the locomotive of a train on the railroad now known as the New York Central, running south of the present Jacobs Avenue just west of Clinton Street, plunged into the old feeder canal when an open bridge was not closed in time. In those days the canal had right-of-way over railroads.

All the locomotive was fished out of the canal at that time except a sand box and the ornamental brass bell decorating the lid of the sand box. The Wabash Railway Company sent a wrecking crew with a hand crane to hoist out the broken locomotive. It was also generally believed that the brass bell, then an important adjunct of any locomotive had remained in the canal.

W. I Martin, 1723 Alabama Avenue, a New York Central foreman, now has been awarded custody of the old bell by Captain of Detectives John Taylor. A long investigation finally disclosed the old bell hidden in a hay loft in this city.

Lost in Poker Game

It has been learned that the bell was recovered from the canal by a member of the Wabash wrecking crew but lost in a poker game soon afterward to Dan Harmon proprietor of the celebrated Harmon House then located at Calhoun Street and Chicago Street The latter street was vacated when the Pennsylvania Railroad elevation was built.

The Bell of the “Fort Wayne,” Missing 65 Years

The bell is now as revealed was atop the Harmon House for 35 years. Mr. Harmon evidently having kept discreetly silent concerning the identity of the famous bell, if he knew that it was indeed the one which had come from the wrecked locomotive.

A year after it had been retrieved from the depths of the feeder canal, the locomotive was rebuilt and christened the A. H. Hamilton, after a then well-known political figure and a railroad executive. The sandbox and brass bell were found 11 years ago when the Indiana Service Corporation built a subway for its Kendallville traction line branch under the New York Central tracks. They were placed in the Ford Museum at Dearborn.

Identified By Veteran

The bell now in Martin’s possession was identified by John Young, 93, a former engineer on the line which owned the old locomotive. He had operated the locomotive before it was wrecked and later after it was rebuilt. The bell was recovered on Young’s birthday, June 28.

Young said that at the time the excavation for the traction subway was in progress, he with Ed Yorick, another veteran engineer, now deceased, watched daily at the scene in the hope that the old bell would be recovered. Neither was aware it had already been found.

An old gong used in the Pennsylvania eating house at the same time the locomotive bell reposed atop the Harmon House has also been recovered by Martin and is a prized possession along with the long-sought old bell. Dr. James M. Dinnen has identified the gong as being the same in use in the old Penny dining room.

The above July 4, 1939 newspaper report says the wreck was in Sept. 1874, but the April 9, 1873 Ft. Wayne Weekly Sentinel reported that is was 5:30 p.m., April 8, 1873. The Aerial map shows the location.

Left column of article says: The bell was retrieved from the feeder canal at the time of the wreck by a member of the wrecker crew. He lost it in a poker game, and it was then atop a hotel for 35 years. It was found in a hay loft, presumably in 1939.

Right column says: The bell and sand dome were found in 1928 during construction of ISC’s underpass of FW&J (at the north end of the OmniSource property) and donated to the Henry Ford Museum. I (Craig) think they meant to say that the sandbox was found, because it then says the bell that was in the hay loft was from the locomotive and still in the possession of Mr. Martin.

In 2015, Charlie Willer told me the locomotive was #409 “Hiram H. Smith”, but this newspaper says it was the “Fort Wayne”.

I saw a photo of Victor Baird at the Ford Museum with the sand dome, but I didn’t save it.

Craig asks “Where is the bell today?”

Whitewater Canal Symposium: A Fun Learning Experience

By Carolyn Schmidt, Photos by Sue Jesse

On Saturday, April 13, 2024, 28 CSI members and guests gathered at 10 a.m. at the Fayette County Historical Museum in Connersville, Indiana for a fun filled day with historical talks, first person interpretation, and tours of the old Whitewater Canal Headquarters and Elmhurst. Those attending were:

CSI *Directors – 12 and other members – 4

*Jerett Godeke, Lowell & *Margaret Griffin, *John Hillman, Sue Jesse, *David Kurvach, *Phyllis Mattheis, *Ron Morris, *Mike Morthorst, *Preston Richardt, *Bob & *Carolyn Schmidt, *Steve & Sharon Williams, Ron & *Candy Yurcak

Guests – 12

Torry & Jenny Amrheim, A. J. Ariens, Christopher Friend, Carolyn Lafever, Teresa Lowe, Clyde Mason, Donna Schroeder, Joey Smith, James Spence, Ron Urdal, Cathy Vandiver

CSI President, Bob Schmidt, welcomed everyone and asked them to note the biographies of the speakers for the day in the program that they were given upon arrival. This would speed things along as there were many topics to cover plus time out for a sack lunch and the society’s annual election of directors and officers. The program “Exploring the Whitewater” had six sessions. Bob made three Powerpoint presentations —”Twists & Turns of Change,” “Canal Mania,” and “The Conwells.” The first two of these are included in this publication. The third will be included in an upcoming issue of “The Tumble.”

Dr. Ronald Morris, a professor of history at Ball State University and a CSI director since 2018, gave a PowerPoint presentation about “Indiana’s State Forest.” He told how the early pioneers cut down so many trees that Indiana’s forests had to be replanted. He explained the difference between Indiana’s 15 state forests that cover about 160,000 acres and the Hoosier National Forest, operated by the U.S. Forest Service that covers about 204,000 acres.. He spoke about the work of the CCC in planting trees, creating trails and building picnic shelters during the great depression in the 1930s. Today many of these trees are approaching the end of their life cycle and are being harvested. These areas are being reforested. He mentioned the famous “Deam Oak” named for Charles C. Deam of Bluffton, Indiana, who discovered it in 1904. It is a cross between a white oak and a chinquapin oak.

At noon everyone had time to visit while eating the sack lunch they had brought with them. The Canal Society provided beverages of coffee, ice tea and water along with dozens and dozens of delicious cookies baked by Margaret Griffin, Sue Jesse, Sharon Williams and Candy Yurcak. The cookies were a BIG hit.

Everyone was invited to stay for the CSI Annual Meeting during lunch hour. Bob Schmidt asked all CSI members in attendance to review the list of CSI directors who were up for election, new directors to be elected and new officers to be elected by the directors that Margaret Griffin, nominating chair, had provided. Minutes of this meeting were taken by Phyllis Mattheis, Secretary Pro Tem and follow this article.

As a change of pace following lunch, Margaret Griffin, CSI director since 2022 and CSI Treasurer, gave a first person presentation entitled “A Cook’s Tale.” She portrayed Sarah “Aunt Sally” Vroom Gonzales, a canal boat cook, who eventually got her man, canal boat owner and captain Valentine Sell. She told about her taking fresh bread, butter and jelly to Lily and Florine Vinton when their boat was in the basin by the Vinton House in Cambridge City. She also took turns at the tiller of the boat on their two-week round trips from Cambridge City to Cincinnati, Ohio. Margaret talked about life on the canal and asked the audience to participate by asking questions.

John Hillman, CSI director since 2018 and past-president of the Whitewater Valley Railroad, spoke about a new book “The Historic Whitewater Valley Railroad: Hagerstown, Indiana to Valley Junction, Ohio” that is available at the train depot in Connersville for $53.45. From Connersville this railroad runs atop the Whitewater Canal towpath and passes by stone canal locks that can’t be reached by the road. Some are almost in pristine condition, others are crumbling. CSI has donated signage for the locks along this route. The logo of the Whitewater Valley Railroad is “The Canal Route.” Volunteers who run the train, replace the rails, clear out the canal locks, etc. come from all over Indiana and neighboring states. They have dinner trains, special event trains, and the most popular “Polar Express” train.

Jerett Godeke, CSI director since 2023 and author of “The Reservoir War: A History of Ohio’s Forgotten Riot in America’s Gilded Age 1874-1888,” passed out fliers about CSI’s upcoming fall tour “Towpath & Warpath” on Saturday, August 17, 2024 covering the Wabash & Erie Canal from Antwerp, Ohio to Junction Ohio. It will be headquartered at the Paulding County History Museum, 600 Fairground Drive in Paulding, Ohio starting at 10 a.m.. Our hosts will be the Paulding County Historical Society and Jerett will be the tour docent. We will have time to tour the 3 wonderful exhibit buildings on the grounds as well as traveling by car along the canal route to canal sites.

Between presentations drawings were held for door prizes, which were duplicate books that had been donated to the CSI archives. Almost all of the visitors won a book about canals. Bob Schmidt thanked everyone for coming and suggested those who were not members join our group. This concluded the symposium and everyone left to take the tours.

Below are pictures taken at the symposium:

Donna Schroeder, Fayette County Historian and Fayette County Tourism President, took the group to tour the Whitewater Canal Headquarters – aka Canal House. The second floor had just been finished to its appearance during canals days in time for the tour. Meredith Helm began building the building, which was purchased by the Whitewater Canal Company in 1842 to use as its headquarters in 1843. When the canal company had financial difficulties, the ownership passed to Samuel W. Parker, president of the company (1848). Over the years it was owned by Dr. S. W. Vance 1857-1936 (operated as a boarding house around 1923 and a veterinarian business in 1928) while owned by the Vance family, purchased by Alice G. Gray, wife of U. S. Congressman Finly Gray in 1936 and from 1947 to 1971 it was owned by the Veterans of Foreign Wars. The upstairs had had walls removed to make a meeting hall. (Donna is in the center of the picture.)

We were then surprised by a tour of “The Old Elm Farm” that was on the west side of the Whitewater Valley, along the former path of the Whitewater Canal in Connersville. Erected in 1831 the four room brick structure was built by Oliver H. Smith, a member of Congress at that time. It had many other residents such as Caleb Blood Smith, Secretary of the Interior under President Lincoln. It was owned by James Shaw in 1838 and Nicholas Patterson in 1842. Its original building was added to several times.

In 1850 Old Elm Farm was purchased by Samuel W. Parker of Brookville for $9. Parker was president of the Junction Railroad Company and the president of the Whitewater Canal Company, headquartered at the Canal House. Remnants of the canal can be seen across the highway from Elmhurst. Canal boats would toll their bells upon passing his home. Parker would respond by ringing the bell he had installed in front of his home. He died in 1859 and was buried on the property.

James Huston purchased it in 1881and renovated it after the design of the White House in Washington, D.C. costing $44,000 to remodel. Huston was appointed United States Treasurer under Benjamin Harrison.

In 1901 Alonzo W. Daum bought it and added twenty six rooms for a nationally known sanatorium. Dr. W. J. Porter operated it as a sanitarium. He renamed “Elmhurst”.

It became a summer home in 1906 and in 1909 the Elmhurst School for Girls was established. Daughters of wealthy and prominent families were educated here until the school closed in 1929. It stood vacant for about a year before an attempt was made to open a private military academy, which failed. It was purchased by Warren Lodge to be used as a Temple in 1939. It was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1977.

Canal Society of Indiana Minutes of Spring 2024 Annual Meeting

Twelve directors of the board were present on April 13, 2024, for the meeting during lunch hour of the Connersville Spring Symposium.

From the Whitewater were Ron Morris, John Hillman, Phyllis Mattheis and Candy Yurcak.

From Ohio were Mike Morthorst and Jerett Godeke.

From southern Indiana were Preston Richardt and David Kurvach.

From Fort Wayne were Bob and Carolyn Schmidt, Margaret Griffin and Steve Williams.

Five members were absent: Tom Castaldi, Jeff Koehler, Sam Ligget, Dan McCain, and Sue Simerman.

All six directors with terms expiring in 2024 were re-elected to the board for another 3 years: Castaldi, Koehler, Ligget, Morthorst, Schmidt and Williams. Two new directors were elected:

The Directors then elected officers to the Executive Committee:

Margaret Griffin made both motions, which were seconded by Mike Morthorst and Steve Williams, and carried.

President Bob Schmidt recognized the following persons:

Mike Morthorst for his past service as Vice-President of CSI, who continues as a director.

Webmaster Preston Richardt, who led the successful fall tour of 2023 with attendance of 25-30 on Saturday, November 6 of Patoka, Parke County and southern IN.

Editor Carolyn Schmidt for planning today’s symposium and producing the printed materials.

Sue Jesse, who presided over the cookies and drinks table in her frogs apron.

Donna Schroeder, Fayette County Historian, Director of Museum and tour guide of the newly refurbished WW Canal House.

Ron Morris, who successfully had 30 Canal Signs placed in Fayette County. A dedication was held on Friday September 8, 2023 at 5:15 p.m. at the Whitewater Valley Railroad yard, inspiring Richardt and Kurvach.

Railroad man John Hillman, who assisted Ron with the signs.

Phyllis Mattheis, for being secretary pro tem and for supervising sign placements in Wayne County.

Three former CSI members were remembered: Jerry Mattheis, Gary Ferris and Steve Simerman. Memorial monies in their names were used to purchase signs.

A check for $400 was presented to Candy Yurcak for Byway signs and a check for $100 was presented to John Hillman for railway signs.

Jerett Godeke passed out flyers for the CSI fall tour of Paulding County, Ohio, set for Saturday, August 17, 2024, starting at 10 am. Details later. The meeting adjourned for the afternoon session of the symposium.

Phyllis Mattheis, Secretary Pro Tem

Twists & Turns of Change

By Robert Schmidt

Every community has a history of its beginning and its change through time. This is the story of the

Whitewater River Valley in southeast Indiana, how it came to be and is today. In the late 18th Century the valley still remained a virtual wilderness. There were no major native villages in the area, it was basically a hunting ground for the native people. Although there were visible earthen mounds of prior inhabitance, native tribes had concentrated in mid-Ohio and along the Wabash River to the north.

As the glaciers retreated 15-21,000 years ago a tremendous outpour of water produced two parallel valleys separated by a 10 mile highland. These valleys both descended over 600 feet and carried the two branches of the Whitewater River, which merged at Brookville and continued on and merged with the Miami River about 5 miles above where all of this water enters the Ohio River. The East fork begins in Darke County, Ohio and extends for 57 miles, while the West fork begins in Randolph County, Indiana and extends for 70 miles. These branches join at Brookville. The route is a series of gentle rapids, but flooding was and is a continuing problem.

Exploration by the French began the 1600s and they claimed the interior regions drained by the Mississippi River for France. While they claimed extensive territory they did not really populate the area. In the 1700s they placed forts along the Wabash River, but they did not reach the Whitewater Valley. In 1749 Pierre-Jacques de Celoron traveled southwest along the Ohio River as far as the mouth of the Wabash, planting lead plates and claiming French ownership, but he did not venture into the Whitewater Valley. The British Colonies were hemmed in at the coast by the Blue Ridge and Appalachian mountain ranges.

The town of Brookville was nearly wiped off the map in six recorded major floods. In the late 1940s plans were begun to build a reservoir for flood control on the West branch of the Whitewater. Preservationists protested this plan and were successful in getting the reservoir moved to the East branch. The Brookville Reservoir was opened in 1974. This is the largest and deepest man-made lake in the state.

Conflict was certain when both countries laid claim to the Ohio country across the mountains. The French and Indian War exploded in 1754 when young George Washington led an expedition near Pittsburgh and a French Officer, Jumonville, was killed and scalped by the supporting Indians. The war concluded in 1763 with the signing of the Treaty of Paris. Canada, all of the area east of the Mississippi and Florida were transferred to Great Britain. Territory west of the Mississippi went to Spain. The impact on the Whitewater Valley was zero, just another absent landlord.

Despite the contribution of colonial forces during the war with France, the British government sought to repay some of the war debt by a series of taxes and regulations. Colonial resistance reached a peak with the Stamp Act. Another great source of unrest was the Proclamation of 1763 preventing future land grants beyond the Blue Ridge mountains. Colonials, who had been promised land, and speculators in the Ohio Company were furious. A tea party in 1773 and a British raid on Lexington & Concord in 1775 brought on a full scale revolution that lasted until 1783. The Peace of Paris brought all lands east of the Mississippi into the United States except east and west Florida, which was transferred from Great Britain back to Spain.

Again the initial impact on the Whitewater Valley was zero as the struggle against the British was at Cahokia and Vincennes, not near the Whitewater.

Virginia had surrendered her grant of lands beyond the mountains in 1784. While the former colonies struggled under the Articles of Confederation (1781–1789), the Congress was able to establish the Land Ordinance of 1785 and the Northwest Territory in 1787. By 1789 enough of the states had ratified the Constitution so that an election was held and a new government installed in 1790.

In 1785 Josiah Harmar, the commander of the American army, established Fort Harmar at the mouth of the Muskingum River to deal with Indian aggression for new settlers. In 1788 Marietta, Ohio, named for Queen of France Marie Antoinette, was established on the east bank of the Muskingum. In 1788 it became the headquarters for the Northwest Territory with General Arthur St. Clair as its governor.

The most important impact on the Whitewater Valley came from Judge John Cleves Symmes. He was born in 1742 in New York and studied law. He was a patriot supporter of the American Revolution and had moved to New Jersey in 1770. He served in the Sussex County militia from 1777–1780. He served in the Continental Congress from 1785-1786. In 1788 he put together a syndicate, called the Miami Company, to purchase land in the Northwest Territory. Symmes had learned from an associate about the fertile land between the Miami and Little Miami rivers along the Ohio River. Using promissory notes received from Congress or notes acquired at a depreciated value, he and his syndicate accumulated $250,000. In exchange they received 311,000 acres of land at 66 cents per acre. In 1788 Symmes moved to the north bend of the Ohio River on the south-western edge of this land grant. In 1789 General Harmar followed and built Fort Washington just east of North Bend to protect the Symmes grant. The Symmes land grant and the building of Fort Washington had a decisive impact on the Whitewater valley, settlers could now safely move into the valley.

John Filson, the original surveyor of the site, suggested a combined name of Losantiville, for the new town across from the Licking River in Kentucky. L is for Licking, os Latin mouth, anti across and ville town from French. Governor Arthur St. Clair arrived in 1789. Since at that time he was the Chairman of the Order of Cincinnati, a fraternal organization of Revolutionary officers, he felt Cincinnati was a better name. Other towns in the area were North Bend on the river and Columbia at the mouth of the Little Miami River.

Fort Washington became a key fort in the northwest Indian wars. In 1790 General Josiah Harmar attempted to raid the Indian village of Kekionga (present day Ft. Wayne), but he returned with a loss of troops on the Maumee. In 1791 General Arthur St. Clair got as far as Fort Recovery, Ohio on the Wabash River where his troops suffered a loss of soldiers and civilians greater than Custer at the Little Bighorn. Finally in 1794 General Anthony Wayne defeated an Indian Confederacy at Fallen Timbers near Toledo.

For the Whitewater Valley, the most significant result of Wayne’s victory was the signing of the Treaty of Greenville in 1795. By that treaty Wayne staked out most of southern Ohio and a portion of the Whitewater Valley for white settlement. The western line of demarcation ran from Fort Recovery to the mouth of the Kentucky River. Today this treaty line is remembered with a historical marker in Dearborn, County and at “Boundary Hill” in Franklin County.

The Land Ordinance of 1785 provided for a standardized system of land survey. The metes and bounds system of the East was to be replaced with a rectangular layout originally suggested by Thomas Jefferson. The surveyed lands were laid out in 36 miles squares (6 x 6) called a Congressional township. Each of the 36 sections equaled one square mile. There were to be designated meridians (range Lines) and a base line to use as reference points for the various sections. In 1798 Congress created the Principal Meridian where the mouth of the Miami River intersected the Ohio River. This just happens to be the western edge of the Symmes grant. Land sales from that point were measured by this meridian. Although not really a consideration at the time, this geographic designation created “The Gore.” For Indiana land measurement the second meridian was near Paoli and called the Initial Point.

What is a gore? The word comes from old English gar or spear. It is a triangular piece of fabric used in dress making or being gored by an ox. The vertical Principal Meridian line created at the river and the 1795 Treaty of Greenville line to the west made a triangular gore.

Nothing really changed until May of 1800 when Congress created Indiana Territory with its capital at Vincennes. The Gore and the rest of what later became Ohio remained Northwest Territory and was still headquartered in Marietta, Ohio.

Although Ohio had a population of about 45,000 in 1801 (less than the 60,000 statehood required), it was growing rapidly and Congress decided to accelerate statehood. Arthur St. Clair lobbied for two states to give the Federalist Party more power, but the Jeffersonian’s only wanted one state with its capital centrally located at Chillicothe. In preparation for statehood Congress moved the Gore into Indiana Territory with its headquarters at Vincennes in Knox County, Indiana. The residents of the Gore were not happy. Vincennes seemed far away.

To provide some relief Governor Harrison created Dearborn County with the county seat at Lawrenceburg in 1803. At that time Henry Dearborn was the Secretary of War in Jefferson’s administration.

William Henry Harrison, the son of Benjamin Harrison V, was born on the Berkley Plantation near Williamsburg, Virginia in 1773. When he was 18 his father died and, with the help of Governor Henry Lee III, he was commissioned as an ensign in the 1st American Legion commanded by General Anthony Wayne and sent to Fort Washington. He was on Wayne’s staff during the Battle of Fallen Timbers and the subsequent Greenville Treaty in 1795. Despite the disapproval of his father-in-law, John Symmes, Harrison married Anne Symmes in November 1795. He resigned his army commission in June 1798. That July President John Adams appointed him Secretary of the Northwest Territory. In 1799 he defeated Arthur St. Clair as the first representative to Congress from the Northwest Territory. In May 1800 Harrison was appointed again by President Adams, to become the 1st Governor of Indiana Territory. He built his home, “Grouseland,” in 1805 and served as governor until the War of 1812, resigning to fight the British. Thomas Posey replaced him as governor and moved the territory capital to Corydon.

As governor, Harrison negotiated more territory from the Indians. He started by securing southern Indiana along the Ohio River in 1804-1805. His Treaty of Fort Wayne in 1809 was extremely important to the Whitewater Valley. It was also called the “12 Mile Treaty” for it added an additional 12 miles to the Gore west of the Greenville Treaty line.

Land patents in the Gore were being issued by 1801 and towns like Lawrenceburg and Brookville began springing up. John Conner operated a trading post near Cedar Grove. By 1815, following the new 1809 Treaty, the towns of Connersville, Somerset and West Harrison were formed.

By 1810 Indiana’s population of 25,600 was distributed equally into the four counties of Knox, Dearborn, Clark and Harrison. Still most of the population was located along the Ohio River.

The Indian threat of the early 1800s was greatly reduced following the War of 1812 and the death of

Tecumseh at the Battle of the Thames in 1813. Kentuckian Richard Johnson gained fame as claiming to have killed the Indian leader. In the 1836 campaign for U.S. president Johnson ran for Vice-President with Martin Van Buren for President under the slogan of “Rumpsey Dumpsey who killed Tecumseh.” Other than the nearby Pigeon Roost massacre near Scottsville in 1812 most of the Indian fighting was in northern Indiana.

Dearborn County went through a massive size reduction after the initial Gore was established in 1803. In 1810 Wayne County was created above the current Franklin County / Dearborn County line. In 1811 Franklin County took the lower half of Wayne County. Then in 1814 the southern portion of the Gore in Dearborn County became Switzerland County with Vevay as its county seat. In 1818 Fayette and Randolph took additional pieces of Wayne County. In 1821 Union County was created from portions of former Wayne, Fayette and Franklin counties, thus the name Union. The final division of the old Dearborn Gore came in 1844 when the area south of Laughery Creek became Ohio County with Rising Sun as its county seat.

John Conner came to today’s Connersville in 1813. He was born in Tuscarawas County, Ohio and moved to Cedar Grove in about 1802. Both he and his older brother William were traders with the Indians. Both married Delaware women. John worked with Governor Harrison in negotiating the “12 Mile Treaty.” He lived in Connersville until about 1820 when he moved to the Indianapolis area. He died in Marion County in 1826 at age 50.

Edward Toner established Somerset in 1815. By 1818 Jacob Wetzel and his sons arrived and began blazing a straight line 60-mile-long trail due west toward Waverly on the White River near Indianapolis. Another pioneer family, the Conwells, arrived around 1820. James Conwell later established the town of Laurel just to the north of Somerset in 1836 about the time of the canal construction.

The twist and turns of change had a major impact on the Whitewater Valley. We see how all of this impacted canal building in the valley.

Canal Mania

By Robert Schmidt

Even before the Erie Canal was completed in 1825, interest in a Whitewater Valley Canal had begun.

William Hendricks, Indiana’s first Indiana representative to U.S. House, was very popular and had defeated Indiana’s Territorial Governor Thomas Posey. Hendricks was very pro internal improvements. He was on the Congressional Committee for Roads and Canals. He became Indiana’s Governor and later served again as Senator. He was influential in supporting the National Road. He was able to get Congress to pass the 1824 bill to build the Wabash Canal, which was later rejected by the state.

In 1818 the youngest Conwell brother, Abram, was sent from Lewes, Delaware to find a good location in either Ohio or the new state of Indiana. He came to Connersville about the time John Conner was leaving. He found the valley location ideal and his brothers James, William and Isaac followed. Each of the brothers eventually settled in different areas: Abram in Connersville, James in Somerset, William in Cambridge City and Isaac in Liberty.

By 1822 Ohio was requesting federal surveys to build a canal or canals connecting Cleveland to Cincinnati.

It was not unusual for residents of the Whitewater Valley to want a canal survey when government officials and other states were pushing for canals. They needed transportation access to the Ohio River. Flat-boating on the Whitewater was never practical.

James Conwell, the oldest, was a Methodist minister as well as a businessman. He and his associate, August Jocelyn, had a meeting at West Harrison in 1822 to gather support for a canal in the valley. With the help of William Hendricks, he was able to get the U.S. government to begin a survey for a canal in 1826. The survey crew had some bad luck when the Chief Surveyor, James Shriver, died of disease and his assistant, Asa Moore, also passed. In 1829 another survey crew under Colonel Howard Stansbury completed the work to Hagerstown, but they concluded that the steepness of the valley (491 ft. drop) and the location of the Whitewater River made a canal impractical and would be dangerously subject to flooding.

Up north, the Wabash & Erie Canal broke ground in 1832 after receiving a federal land grant in 1827. The Chief Engineer, Jesse Lync Williams, of that project was then sent by the Legislature to again review the Whitewater Valley. Noah Noble, Governor of Indiana, was from Brookville and wanted a bill of Internal Improvements for the entire state not just the W & E Canal. Williams reviewed the engineering for a Whitewater Canal and under political pressure said it could be done.

James Conwell became an influential merchant in Somerset and in 1831 changed the town’s name to Conwell Mills. Knowing the route of the proposed canal he established the town of Laurel at the northern edge of Conwell Mills in 1836. Later the two small villages were combined as Laurel, named for a town in Maryland. In January 1836 Governor Noah Noble signed the Mammoth Internal Improvements Bill that impacted the entire State of Indiana.

The Whitewater Canal from the beginning not only faced the problems of the river geology, it also faced a problem of geography and politics. The 1st Principal Meridian that was of little concern in 1798 now ran through the high hills at the Ohio state line. Indiana could either transship by rail over the hills or build the canal seven miles into Ohio and then turn back into Indiana toward Lawrenceburg located on the Ohio River. There was insufficient water at the summit to build such a canal.

Ohio was busy building her two canals begun in 1825 and was not too interested in building any others. She agreed that Indiana could build in Ohio if, in the future, Ohio could build a branch canal beginning at the dam at West Harrison. Indiana had little choice, but this was a fatal mistake in the long run. The State of Ohio never built the connecting canal, but in 1838 private investors did. They called this canal the Cincinnati and Whitewater Canal. In didn’t get completed until 1843, delayed by economic conditions and the necessity to build a 1800-foot-long canal tunnel on William Harrison’s farm at Cleves, Ohio. A deep cut canal was considered at this point but was projected to be more expensive.

After groundbreaking at Brookville, Indiana in September 1836, the Whitewater Canal was soon completed to Lawrenceburg by 1839 and was operational for about 10 years until 1849, when unrepaired flood damage closed this route. For 2 years from 1840—1842 construction by the state stopped due to Indiana’s financial crisis.

In January 1842 new hope for a canal arose when private investors from Cincinnati and the Whitewater Valley created the White Water Canal Company. The new company completed the partial works of the State and reached Laurel by October 1843. Unfortunately for the investors, the Cincinnati & Whitewater Canal was also completed that same year and competed with the Lawrenceburg route.

Not to be discouraged, the Whitewater Canal reached Cambridge City and the National Road by

the fall of 1845. Although the original State plan for the canal was to reach Hagerstown, the private

investors said “No.” Hagerstown merchants privately invested in the Hagerstown Canal Company and finished the 8 miles of canal to their town by 1847.

Whitewater Canal Company

The Headquarters of the White Water Canal Company was established in a two story building in Connersville built in 1842. This building still stands today. In 1842 its first president was James Conwell followed by Samuel W. Parker and later John Newman.

From the dam at West Harrison to Lawrenceburg the Whitewater Canal route was just 12-miles-long with four locks. It ended in that small village of 3,000. The town was about 48 feet above the low level of the Ohio River. There was no direct lockage into the river.