Index:

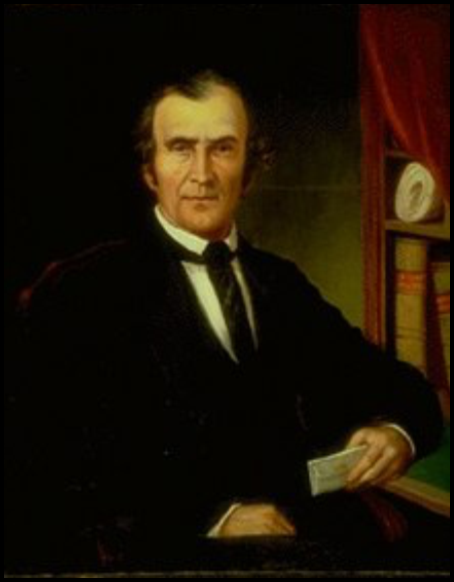

Henry Clay Moore (1813-1889)

Find-A-Grave # 139312595

By Robert F. Schmidt

A convention of delegates gathered in Brookville in 1823 to discuss the possibility of building a canal along the Whitewater Valley. This group was successful in getting the U.S. army to assign Colonel Shriver to make a survey for a canal. He got as far up the valley as Garrison Creek, just north of Laurel, and died. He was replaced by a Colonel Stansbury who completed the survey. Despite the hopes of valley residents the conclusion was that the valley was too steep and presented too many obstacles for a canal. For 10 years nothing more happened in the valley, but the U.S. Government did give a grant of land in 1827 for a Wabash canal in northern Indiana. With that project underway in 1832 attention to canals was sparked throughout the state.

Whitewater Canal enthusiasts would not give up and were successful in getting the Indiana Legislature to authorize another survey in 1834. This survey was to extend from Lawrenceburg on the Ohio River to Nettle Creek near Hagerstown in Wayne County. William Gooding was employed as Engineer-in- Chief and Jesse Lynch Williams was to be his assistant. Williams had been hired as the Chief Engineer on the Wabash & Erie Canal, which was begun in Fort Wayne in February 1832. This 2nd survey resulted in a favorable opinion that a canal was feasible and desirable.

The Whitewater Canal was authorized by the Mammoth Internal Improvement Bill of 1836. Construction on the canal began in Brookville on September 13, 1836. Some of the engineers who were involved in surveying and construction of the canal were: Henry C. Moore, Stephen D. Wright, Simpson Talbot, John Minesinger, John Shank, Martin Crowell, and John H. Farquhar. In the September 2015 issue of The Hoosier Packet we learned about John Minesinger and his work on the Hagerstown Extension from Cambridge City.

Will the Real Henry C. Moore “Please Stand Up”

From 1956 to 1968 on CBS television there was a popular TV Show called “To Tell The Truth,” hosted by Bud Collyer. Three contestants each claimed to be the same person and the four panelists raised questions to try to identify the “real” person. In the May 2016 issue of The Hoosier Packet we gathered information about canal work done on the Whitewater Canal by an engineer, Henry C. Moore. Based on the location of Henry Moore’s property near the work and a grave for Henry Moore in Shelbyville, Indiana, we thought this Henry Moore was the one mentioned in the canal documents and in information that we had uncovered for Henry C. Moore. We were mistaken. Although we stated that the 1850 Census listed him as a farmer and not an engineer, we did not think this odd since back then even a lawyer, George W. Julian from Centerville, worked in his younger years as a rod-man on the Whitewater Canal. Many locals found employment on canals.

By having the article about Henry C. Moore listed under Canal Biographies on the CSI website, Charles Coutellier, an astute observer, found that his information on Henry C. Moore, who had worked as an engineer in Logan County, Ohio, was different from ours. He contacted CSI and raised questions concerning “the real engineer.” Thanks to Charles we can now relate the true story of this Whitewater Canal Engineer.

Henry Clay Moore was born January 7, 1813 in Beaver county, Pennsylvania, which is about 30 miles northwest of Pittsburgh at the confluence of the Beaver and Ohio rivers. We know little of his family or early education. From later sources it appears he had some training in math and engineering from local academies and colleges. In 1831, at age, 18 he was working as a rod-man on the Beaver Extension of the Pennsylvania Canal. That same year Dr. Charles Tilliotson Whippo came to Pennsylvania from New York, where he had worked on the Erie Canal. Dr. Whippo was a physician and a civil engineer. He became Chief Engineer on the Beaver Extension. Perhaps he even hired Henry C. Moore, but for sure they knew each other well. In 1832, Dr. Whippo moved his family to New Castle, Pennsylvania located in Lawrence county just north of Beaver county. Henry soon was promoted to an assistant engineering position.

The Beaver Extension was begun in 1831 and consisted of 30 ¾ miles of canal and slackwater. This portion was completed in 1834. The next phase northward for 61 miles was the Shenango Division and wasn’t approved until 1836. John Minesinger was also working with Dr. Whippo but in 1834 he went to the Whitewater Canal in Indiana to assist in a survey there and returned later to Pennsylvania. See Canal Biographies on the CSI website.

In 1835 Dr. Whippo and Henry C. Moore took an assignment in Indiana to find and survey the future route of the Wabash & Erie Canal from Lafayette to Terre Haute. Charles T. Whippo reported their findings to the Indiana Legislature on November 23, 1835. This full report was printed in The Hoosier Packet December 2016. At this point they returned to Pennsylvania to work on the Shenango Extension. Henry became Principal Assistant Engineer on this project. John Minesinger, who also had returned from Indiana, also worked on the Shenango Extension. Minesinger stayed in Pennsylvania until 1847 until he became Chief Engineer for the Hagerstown Extension back in Indiana.

Dr. Whippo’s daughter, Amelia Ann, was born October 28, 1818, in Henrietta, New York. Henry Moore was closely associated with the Whippo family so it is no surprise that he was attracted to Amelia. He proposed and they were married September 12, 1837 at New Castle, Pennsylvania. She was almost 19 and Henry was 24. On June 19, 1838 the couple’s first child, Robert Moore, was born in New Castle. Henry continued his work on the canal until a turn in politics forced him to change his location. First the family moved to Logan, Ohio where Henry was employed on the Hocking Lateral Canal. In 1836 he again moved, taking his family to Connersville, Indiana on the Whitewater Canal.

Henry was fully employed as an engineer on the Whitewater until November 1839 when construction ceased due to Indiana’a financial difficulties. The canal had been completed from Brookville to Lawrenceburg and Henry was appointed Superintendent. Construction work on the canal did not resume until until July 1842. It was completed by 1845.

In September 1840, Henry and Amelia had another son, Charles Whippo Moore, who was born in Connersville where they had established a residence. Then in April 1843 their daughter, Mary Stibbs Moore, was born there. Amelia returned to New Castle, Pennsylvania, where their third son, Franklin Moore, was born on July 6, 1845. They both returned to Connersville, but tragedy struck on December 11, 1845, when Amelia was struck with illness and died at age 27. She was buried in the Connersville Cemetery.

Henry had gone into a joint milling business in Connersville with Luther Caswell. Perhaps Mary Caswell, Luther’s wife, was able to assist Henry with the four small children. Again tragedy struck and infant Franklin died in June 1846. For a period of time Henry’s children must have been sent to Pennsylvania since he mentions in a letter dated October 25, 1846 to his uncle by marriage, Judge Daniel Askew, that he plans to come to see his children. Henry needed a wife as a companion and for all the domestic chores of raising a family. He courted 23 year old Susan North of Butler county, Ohio. They were married there on August 22, 1848. Together they had a son, Philip North Moore, who was born on July 8, 1849. But only 6 months later on March 24, 1850, Susan died at age 25.

In the early 1850s Henry returned to civil engineering and, like John Minesinger, got into the railroad engineering business. He was involved with several railroad projects. One was the Indiana Central Railroad from Richmond to Indianapolis. Perhaps it was at this time that he met 24 year old Amanda Rogers Atwood. They were married in Wayne county, Indiana on October 10, 1855.

The railroad business caused them to move to St Louis Missouri where they remained for the rest of their lives. Their children were all born in St Louis as follows:

Caroline Atwood Moore, 1856

Henry Clay Moore Jr., 1859

John Atwood Moore, 1861

Daniel Atwood Moore, 1865

Paul Moore, 1868

Henry continued to work on railroad engineering until his retirement. He belonged to the Engineer’s Club of St Louis, who prepared his obituary. This supporting document follows this article and shows all the different railroads on which Henry worked.

Some of Henry’s sons pursued careers in civil engineering and mining. His 3rd wife, Amanda, preceded him in death on October 31, 1886 at age 56. Henry died at age 76 on April 13, 1889. Both are buried in Bellefontaine Cemetery in St Louis. Missouri.

Sources:

Ancestry.com: Public Member Trees: Henry C. Moore, U.S. Federal Census Records

Fox, Henry Clay. Memoirs of Wayne County and the City of Richmond, Indiana. Madison, WI: Western Historical Association, 1912.

Journal of the House of Representatives at the Twenty-fifth Session of the General Assembly of the State of Indiana Commenced at Indianapolis, on Monday, the Seventh Day of December, 1840. Indianapolis, IN: Osborn & Chamberlainm, Printers to the State, 1840.

Letter to Daniel Agnew, Esquire, Beaver, Beaver County, Pennsylvania from Henry C. Moore, Oct. 25, 1866, postmarked Oct 26, 1866 Connersville, Indiana.

Meier, E. D., Member Engineers’ Club of St. Louis. Henry C. Moore—A Memoir. Read to club on May 15, 1889.

Miller, James M. “The Whitewater Canal,” Indiana Magazine of History, Vol. 3, No. 3, 1907.

Report of Milton Stapp, Esq. Late Fund Commissioner of Indiana to the General Assembly December, 1841. Indianapolis, IN: Dowling and Cole, State Publishers. 1841.

Henry C. Moore Genealogy

Documents in Support of the Henry Clay Moore Article

The Disputed Contract Settlement

In 1840 a dispute arose in Daviess & Gibson counties in southwestern Indiana on the Central Canal between the canal contractors, Hugh & Robert Stewart and the State of Indiana. The dispute concerned the value of work that they had performed in excess of what they felt to be that estimated by the canal engineers.

At this time, due to the state’s financial crisis, work had been suspended on both the Whitewater and the Central Canal in November 1839 and contractors were trying desperately to get some payments for the work in progress. On the Whitewater Canal, work had stopped with the canal only completed between Brookville and Lawrenceburg. On the Central Canal near Evansville, only the 18 miles out of Evansville had been completed to the Pigeon Creek Dam near Millersburg. Some work was also done near the Pigeon Summit in Gibson County. The contractors, R & H Stewart had presented their claims to an arbitration board for additional payments due to their contention that work had been required that was not in the original estimates made by the project engineer and losses were incurred due to the work stoppage. This board had allowed the following charges, which amounted to $10,000, to settle this claim but the contractors still felt it was not sufficient.

Sections 121-125 Pigeon Summit Sections 69 & 70

Losses on shanties & wells for workers $249.00 $417.00

Tools/wagons/ploughs/horses 126.00 582.30

Engineering changes 4,137.87 3,840.00

Other allowance 1,022.84 —-

Total Board allowed 5,535.71 4,839.30

Lazarus Wilson, an engineer who had previously worked on canal and National Road surveys and construction, was at that time working on surveys for the Madison & Indianapolis railroad near Madison. (See The Hoosier Packet Sep 2009). Wilson was asked to be a member of the arbitration board to review the Stewart claim. He was the one dissenting member, either to the claim entirely or the amount of the proposed $10,000 settlement.

The Commissioners of the Canal refused to issue the payment agreed upon by the board and the case when to court in Daviess and Gibson counties. The case was not settled by the courts but was next sent to the state legislature for resolution. The Stewarts asked that another engineering review be performed, so William J. Ball, Resident Engineer of the Cross-Cut Canal, was selected by Jesse Williams to perform this re-estimate. He came back with an estimated value closer to $15,000 vs the $10,000 offered earlier. The Board of Commissioners concluded that some of the values that Ball used were incorrectly applied and they rejected his valuations.

Noah Noble, who at this time was ex-Governor and was at this time head of the Board of Canal Commissions, stated in his report to the legislature the following:

“It is ordered, That the whole subject for its final adjustment be referred to T.A. Morris, late resident Engineer on the Madison and Indianapolis road; Wm. J. Ball resident Engineer on the Cross-Cut canal, and H.C. Moore, late resident Engineer on the Whitewater canal, with a request that they meet as soon as practicable on the line in question; procure from the late acting Commissioner and Engineer, all field notes, specifications, notice to contractors etc; and proceed to examine said work, and report their joint decision and estimate to the Board.”

“Mr. Ball being obliged to decline the appointment in consequence of engagements calling him from the State, the resident Engineer on the Wabash and Erie canal, Stearns Fisher, Esq., has been appointed to fill his place.”

After these three men visited the site on January 11, 1840, they concluded that the settlement amount should be $1,589.10. The petitioners claimed that these men did not actually measure the contested area but merely reviewed the prior data used by William Ball. The committee of the legislature now reviewing the data concluded that the three man review was sufficient and that the Stewarts should be paid the $1,589 and that no further legislative action was required.

In a December 1841 report to the Legislature by the Board of Internal Improvements several comments are of interest. Stearns Fisher is listed as a superintendent of construction for the Steam Boat Lock at Delphi. His compensation is not shown. The four toll collectors on the Wabash & Erie Canal at Fort Wayne, Lagro, Logansport and Lafayette were being paid $15 per month ($225 per year). T.A. Morris is the Resident Engineer on the Madison & Indianapolis Railroad and the Central Canal with a yearly salary of $1,500. Henry C. Moore is employed as superintendent upon the Whitewater Canal at a salary of $1,000 per annum. Two collectors of tolls were employed on the Whitewater canal, one at Brookville and the other at Lawrenceburg, each with a yearly salary of $100.

Henry’s Letter from Connersville to His Uncle Judge Agnew in 1846

Addressed to Daniel Agnew, Esquire, Beaver, Beaver County, Pennsylvania from Henry C. Moore, Oct. 25, 1846 and postmarked Oct. 26, 1846 Connersville, Indiana.

Connersville Oct 25th, 1846

Dear Daniel,

As I have neither written to you, nor heard from you for some time, I conclude it is time I was writing you, lest you should forget there is such a one as I in the land of Hoosierdom.

I have been exceedingly busy this summer and fall repairing the [Whitewater] canal and attending to my mill. Have got the canal again in successful operation and the mill is just about done – 2 run of stones have been partially in operation for the last 10 days, but they are not yet in proper order. The mill wrights will get all done this week and then as soon as the miller can get the stones in proper order, we will be ready to go ahead; and I think we will be able to make 150 bushels per day after we have run awhile.

We have made an arrangement with an extensive flour dealer to grind for him all the wheat he can send us and also to buy for him all that can be bought in this place — he furnishing us the money to do it and we manufacture for the toll which is in this state the 1/8 part. Our contract is

exactly thus– viz, we give him a barrel of flour for every five bushels of wheat he furnishes to us, we finding the barrels and keeping all the offal bran, etc., and in addition he pays us 14 cents in cash for each barrel, which with the offal we estimate will pay us for the barrels. By this arrangement if we can get wheat enough or anywhere near enough to keep the mill going, we must do very well. We are perfectly safe and know what we are making all the time, whilst he is running all the risk if any. We are also to do all the custom work for the country that offers. We must, if we have no bad luck by this arrangement, clear some 2 to 3,000 dollars this year.

I was in Cincinnati, Ohio last week and got the mill insured to the amt. of $5000 which cost $97.50 premium—about 2 per cent.

I suppose this plan of operating will set you and some other of my Pa [Pennsylvania] friends at rest for the present, lest I should be broken up and ruined by this mill forthwith. But my dear sir, if we had had money to have bought wheat in July and Aug when it was at 40 to 45 cents, see what we could have done. Now we are paying 58 cents and have paid as high as 63. We are buying from 200 to 500 bushels per day and have now on hand in the mill about 8,000 bushels and there is some 10,0000 more up at Milton, which boats are now bringing down as fast as they can. We ought to get in 30,000 bushels this fall to keep us going in the winter.

And so Pa has become Whig at last, but she has delayed her repentance too long, for now she has lost the tariff and never can get such another, but still I am glad, as a son of the old state, to have her do right even once in a while. Jim Power is now one of the greatest men out—the eyes of the whole nation are on him as the representative of the Pa Whigs, and there is no telling what we are to come to in this world, but I’m glad he is elected. He is a good dear fellow and my friend. I saw Dan [Stone or Stirn?] in Cincinnati and he told me Caroline was great sick. How is this and what is the matter? Nothing serious I hope. Let me hear about it. Whenever you have any money to lend, let me know. I’ll take $1,000 or so and secure you any way you require in reason. I can use money here at any time now to good advantage and make more than the interest out of it.

I think I will be up about the last of Nov. to see my children and friends in Pa for a short time.

We had the Methodist conference here week before last—Bishops Hamline and Morris here—I heard Hamline preach—he is very fine but was rather overshadowed by Mr. Simpson, the President of the Indiana Asbury University. He eclipsed everything in the way of preaching –I had Mr. Daily, late Chaplain to Congress, to room and sleep with me. He is a clever social fellow and quite a fashionable man and pretty smart. I became quite well acquainted before he left and like him very well. Hamline is to preach a dedication sermon on next Sunday at Laurel 10 miles below here. I think I will go down and hear him.

Remember me to all the family.

Yours truly, H. C. Moore

Observations on the Above Letter:

Henry C. Moore addressed his letter to Judge Daniel Agnew, his sister Elizabeth’s husband. This was a political family. Their father Robert Moore was a U.S. Congressman (1817-21) from the 15th District of Pennsylvania. He was a Democrat. Robert died in 1831. It appears that Henry and his uncle Daniel are favoring the Whig Party. Henry’s wife, Amelia Whippo, had died the year before in 1845. It appears that Henry’s children were sent back East for a time. He inquires about the health of his younger sister, Caroline. She died 6 months later in May 1847 at age 22. He states that “we” have gone into the milling business. In the 1850 Census Henry is living with the Luther Caswell family along with his children, who are now back in Connersville.

Some others mentioned in the letter:

James M. Power (1810-1890) was the son of a prominent politician of Pennsylvania, Samuel Power. He built a large portion of the Erie Extension of the Ohio and Pennsylvania Canal; was a successful merchant and iron manufacturer for a number of years in Mercer county; was elected on the Whig ticket in 1847 as canal commissioner and in 1848 was appointed by President Zachary Taylor, Minister to Naples and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. He made the first and only improvements, under a contract with the federal government, that ever were made prior to the completion of the Davis Island dam, on the Ohio River, from the mouth of the Beaver River to Pittsburg. Those improvements can still be seen during low water today.

Leonidas Lent Hamline (1797-1865) was an American Methodist Episcopal bishop and a lawyer. He studied ministry and then law, the latter which practiced in Ohio for a while. In 1830 he began preaching in the Methodist church. When it became divided over slavery, he drew up the plan of separation that he presented to the General Conference, the church’s legislative body, in 1844. He put up $25,000 of his money to start a school, which became Hamline University. He was the first editor of the Cincinnati-based periodical, The Ladies’ Repository, and Gatherings of the West. The two volume set of Works of L. L Hamline, D. D., by Rev. F. G. Hibbard contain a number of his sermons.

Matthew Simpson (1811-1884) was elected an American bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1852 and was based in Chicago. He played a leading role in mobilizing the Northern Methodists favoring freed slaves.

Thomas Asbury Morris (1794-1874) was elected an American Bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1836. He was a Methodist Circuit ride, Pastor, Presiding Elder, and Editor of the Western Christian Advocate.

William Mitchel Daily (1812-1877) was ordained a deacon of the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1833, and an elder in 1835. He was made agent for Indiana Asbury (now Depauw) University. He chaired the first session of the newly created Indiana State Teachers Association in 1854. He was the third president of Indiana University.

Henry C. Moore—A Memoir

By E. D. Meier, Member Engineers’ Club of St. Louis.

[Read May 15, 1889]

The early dawn of the 13th day of April brought to a brave man in our midst the only relief he could hope for. After months of suffering, borne with the courage and stoicism so characteristic of the man, our friend, Henry C. Moore, laid down his burden.

Born Jan. 7, 1818, in Beaver, Pa., young Moore, at the age of eighteen, having profited by such meager mathematical training as Western Pennsylvania academies and colleges then afforded, began his engineering career as rodman on the Beaver division of the Pennsylvania canals. Where now three railroads contend for the trade of the narrow but prosperous Beaver Valley, dotted with furnaces and forges, the State was then but beginning a single branch of its system of water ways.

Fifty-eight years brought many changes in engineering methods, and in the character of the works to which they were applied, and it was the fortune of our friend not only to see but to manfully share the work of the great development. The three-score years given as man’s average span of life were almost covered by Moore’s active work as an engineer. In eighteen months we see him as an assistant engineer, and two years later, his work there completed, he locates a canal from Lafayette to Terre Haute, Indiana. In 1836 he becomes Principal Assistant Engineer on the canals of his native State, and in three years more completes the 63 miles of “Erie Extension” canal from New Castle to Conneaut Lake Reservoir.

A turn in the wheel of politics now throws him out of employment there, but he at once finds work in his line in Ohio, and soon after becomes resident engineer of the White Water Canal in southeast Indiana, and rises in 1842 to be its chief engineer and superintendent. But new highways of trade more suited to American enterprise are superseding the ancient water ways, and in 1849, in the vigor of his early prime, well equipped with the knowledge of the soils and rocks he is to level for the track of the greatest of modern conquerors, Moore begins building railways.

First, the strap rail, then the low T-rail, with its chairs and rough joints; from Howe truss bridges on piers of piles, on slowly and painfully through the cast iron stage to the evolution of the heavy steel rail, with Sampson fishings [finishings], stone-ballasted track, steel cantilever bridges, etc.; from the 40-foot passenger car with its torturing, stiff-backed seats to the vestibuled palace trains of to-day, he has seen all the stages of development, and has argued and solved the many problems which confronted the engineers of the fifties, sixties and seventies, whose work now, in the fittest survivals, fills the text books of our American engineering schools. He builds from Rushville to Shelbyville, Ind., from Hamilton, O., to Indianapolis; next, in 1851-52-53, he locates and constructs the Indiana Central Railroad from Richmond to Indianapolis; thence locates from Indianapolis to Evansville, 155 miles, and grades 55 miles more to Washington, Ind.; next, as chief engineer of the Marietta & Cincinnati Railroad, builds from Athens to Marietta and the branch to Belpre; in 1859 he becomes Superintendent of the Western Division of the T.H., A. & St. Louis, and moves to our city; in 1864 he rises to the general superintendency of the entire road, now the St. Louis, A. & T. H.; in 1868 he takes charge of the Missouri Pacific Railroad, but just completed to Kansas City. Here in 1869 the change of gauge from 5 feet 6 inches to 4 feet 9 inches became necessary, and his directors ask him to do this in one week. His answer is the completion of the whole 309 miles in one working day, without the delay of a single mail train.

In 1871 he builds the St. Louis, Lawrence & Denver Railroad from Pleasant Hill to Lawrence, 61 miles; next as Chief Engineer and Superintendent of the Indiana & Illinois Central he builds the 152 miles from Decatur, Ill., to Indianapolis, and remains with the road till 1880. In 1881 and 1882 he builds the 140 miles of the Indianapolis, Bloomington & Western from Indianapolis to Springfield, O.

We find him on our Club’s record from 1881 til his death, and the year 1883 places him on a list of our presidents.

The salient points of his character as they impressed his life-long associates were his broad and sterling honesty, manifest alike in the accuracy and justice of his pecuniary transactions, in the directness and clearness of his professional work, and in his capacity for seeing the true relations of things; his tender sensibilities shown alike to family, friends and employees; and his stern and uncompromising hatred of trickery and injustice.

Uncomplaining in the severest pain, gratefully appreciative of the ministrations of his children, fully understanding his malady and bowing to the inevitable, he died, as he had lived, a true type of American manhood.

In the rapidity and thoroughness of his work, born of the most thoughtful and painstaking preparation, in the stern and unbending justice of his executive management, in his active interest to the last in all sound progress in our noble profession, in the cheerful and kindly sympathy which endeared him to his friends, we gratefully pronounce him a model engineer.

To his family he leaves as fairest legacy the story of his long and successful professional life and the remembrance of his manly virtues; that we cherish them both and take honest pride in inscribing them on our records will, we trust, be to them the truest evidence of our sympathy.

On behalf of the Engineer’s Club of St. Louis.

Petersburg Canal Marker

By Carolyn Schmidt

In preparation for the nation’s bicentennial, citizens of Petersburg, Indiana placed a sign on a building that was a former depot for the Wabash & Erie Canal. On August 27, 1975 the following article about erecting the sign and the history of the canal appeared in The Press Dispatch of Petersburg. Please remember that when the article says today, it is referring to 1975.

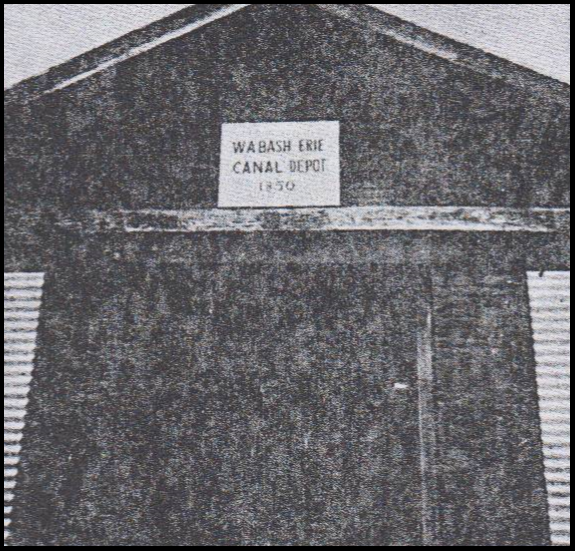

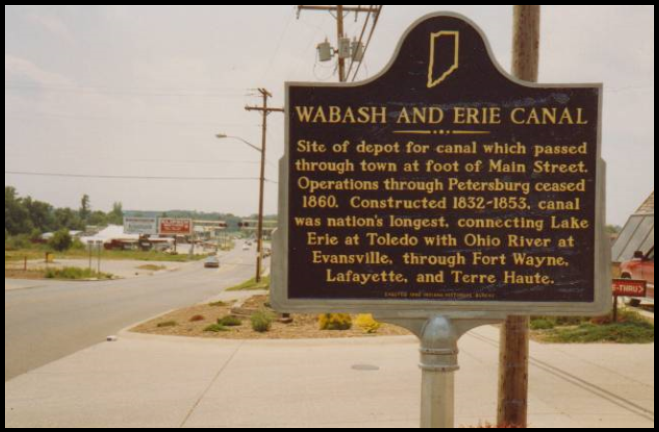

“Put Sign On Former Erie Canal Depot

“A sign, identifying the Wyatt Seed Warehouse as the Wabash Erie Canal Depot, was installed Wednesday, August 13 by the Pike County Bicentennial Committee. The sign was furnished by Mr. and Mrs. R. L. Cox of Petersburg.

“Indiana and Ohio became caught in the canal craze after observing the unqualified success of inland waterways along the Atlantic seaboard. Consequently, the two states conceived the Wabash and Erie Canal as a joint venture to boost their economies.

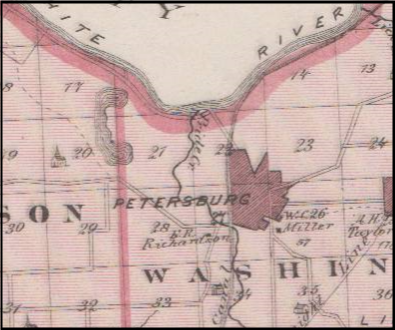

“In 1850 the canal was completed to Petersburg from Toledo, Ohio, through Lafayette, Terre Haute and Worthington, proceeding via the White River system to Newberry and Petersburg. The aqueduct over White River was completed in 1848. It was 557 feet long having six spans of 85 feet clear space and sustained by five piers 42 feet high above the low water mark. The piers and abutments were of stone cut masonry. These were built so substantially that the south pier of the aqueduct is still used by the Penn-Central Railroad.

“The canal then entered Pike County in Section 7, paralleling White River to a point one mile due north of Petersburg. It continued in a southwesterly direction through Washington and Patoka Townships, leaving Pike County in Section 32, Logan Township. In that section aqueduct number 17 was built over Patoka River, entering Gibson County just above Francisco.

“The Petersburg-Evansville division of the canal was let by contract to Mr. Hosmer, Mr. Sturgess and Mr. Forrer on September 6, 1850. Upon entering Gibson County it intersected Pigeon Creek. Flowing through Warrick County the canal began a gradual 51 feet drop, which required the erection of seven locks to enable towboats to reach the Ohio River. The canal flowed from Chandler to Evansville along the right-of-way now occupied by the Southern Railway. The railroad tracks are presently laid on the old canal towpath.

“It continued to Canal Street in Evansville and eventually to the Ohio River [Pigeon Creek]. On June 25, 1853 the Evansville division was so far completed as to admit the passage of water to the southern terminal and the contractors were paid.

“The construction of the Wabash and Erie Canal was quite an engineering feat. Hoards of Irish immigrants worked in groups of 40, shoveling dirt out of the new canal bed into a seemingly endless line of empty, waiting carts.

“Some of the workers were paid as much as a dollar a day, receiving as part of their salary one-fourth pint of whiskey, four times a day. It was a wild and raucous group. After finishing their sunrise to sunset working day, some of them drank even more whiskey. It was not at all uncommon for the evening to end in a drunken brawl.

“The workers were a tough and earthy breed. They had little regard for even the most basic rules of cleanliness. Their unsanitary practices culminated in an epidemic of cholera, an intestinal infection which fatally dehydrates its victims.

“The cholera struck Pike County in 1850. The first death was a child of an Irish canal worker. A few days later the man himself took the disease and died. From these cases the disease spread rapidly among the workers on the canal and large numbers of them died. People saw wagonloads of corpses being hauled, usually at night, to Washington [Indiana] where a priest administered last rites. Then they were often buried in a common grave or sometimes cremated.

“Citizens of Petersburg became panic stricken. At one time the town was almost depopulated, with only 12 families remaining. Dr. Alexander Leslie and Dr. J. R. Adams remained at their posts and did much to relieve the suffering and prevent the further spread of the disease.

“Among those residents of Petersburg who died of cholera were Malachi Merrick and two of his children, Mrs. Emiline Connelly and two or her children, William Benjamin and Mr. and Mrs. George Barnett. Most of the victims were buried in the old town cemetery.

“The Wabash and Erie Canal had a brief and troubled existence. It was heavily used, but the tolls did not pay the expenses. Many kinds of boats could be seen on the canal. There were freight boats, those carrying both passengers and freight and passenger boats. As a public highway, anyone who could pay the tolls could travel on it. Boats were pulled by mules or horses at a rate of 100 miles a day [This would be traveling both day and night. 24 hrs. x 4 miles per hr = 96 miles]. The driver, called a hoggee, either rode one of the animals or walked, while a pilot steered the boat. This provided inexpensive travel for both passengers and freight.

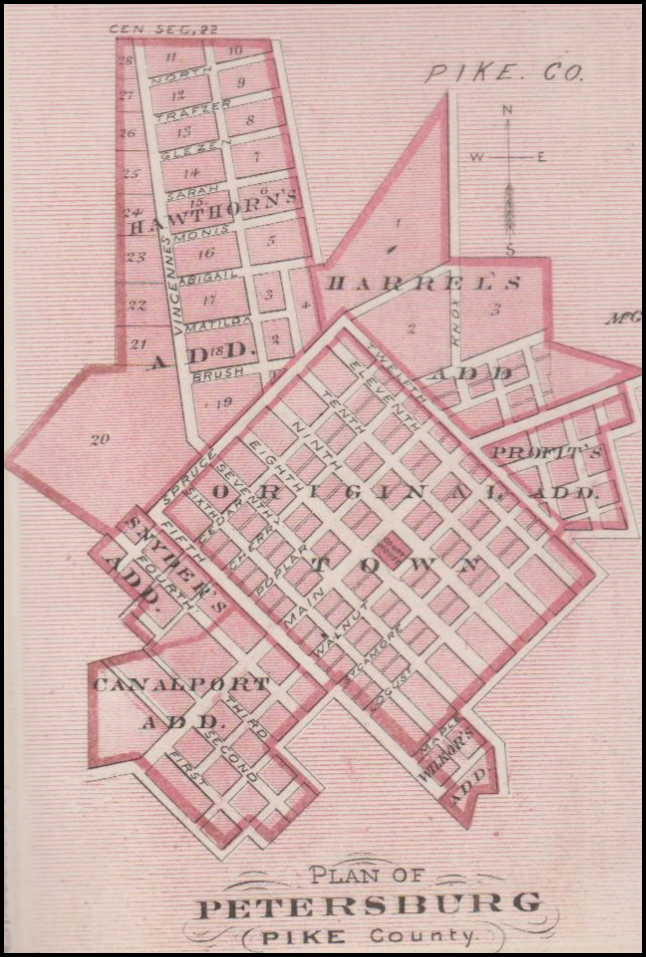

“For a few years at least, the canal was a boost to the economy of Pike County. A brick building still standing on Main Street, was erected for use as a passenger depot in Canalport, a division of Petersburg. [In the 1876 Indiana State Atlas, the Canal Port Addition to Petersburg is clearly seen. The Pike County map shows the canal route.] Another frame building served as a freight depot. Numerous smaller stores and shops went up along the canal, near where the Farm Bureau now is. It was a busy and exciting place to be when the boats came in. Pike County farmers hauled their grain and livestock to Evansville. This stretch of canal was used long after it was abandoned to the north.

“However, various problems plagued the canal throughout its operation. During the winter, ice rendered a major portion of the canal impassable. Spring thawing brought a tremendous increase in water volume and pressure ruptured dikes and retaining walls.

“Aqueducts were drained by people opposed to the canal. They argued these served as breeding grounds for disease. Other vandalism resulted because of hostility of those opposed to the large expenditures in building and maintaining the canal.

“The canal in Indiana had a price tag of $20 million, an immense sum in the 1850s. This left the 500,000 citizens of Indiana with a per capita debt of $40 each. So awesome was the debt caused by the Wabash and Erie Canal, the present state constitution, ratified in 1851, prohibited Indiana from going into debt again. As a result, Indiana has been required to operate on a pay-as-you-go basis ever since.

“In 1854, the railroad was completed from Evansville, through Petersburg and to Terre Haute and rail connections were available to the East and West. This provided a much more efficient means of linking this area with the rest of the world.

“The canal was doomed. Over the years the canal has been packed with earth until only a few short stretches of it remain. Some water is still contained in the old canal bed at Clark’s Station, four miles south of Petersburg, as well as in a few other places.

“The noisy revelry of construction gangs, the shouted orders as towboats docked in Petersburg and the steady gait of strong mules as they pulled crammed towboats through the quiet countryside have dissolved into history. Yet, all the canals were part of an important period in growth and settlement of this area when it was young.

“They were a way of moving men and goods to the frontier when this growing country needed to strengthen her commerce and develop the promise of her bountiful territory. In Pike County alone, many of our most highly respected and productive citizens are descended from men who came here when the canal was under construction and chose to make this their home.”

After the residents of Petersburg had been reawakened to the importance of the canal by the newspaper article and the sign placed on the depot building, the building continued to deteriorate through the next ten years. An article in The Dispatch of Petersburg on Thursday, October 31, 1985 carried the headline “Dilapidated Wabash-Erie depot demolished; repair not feasible.”

It said that “one of the last signs in the county of the “Big Ditch” is gone. The Wabash-Erie Canal depot building was toppled Thursday morning. At one time the building was the loading and unloading point for many a traveler and commodity that came to (and left) Petersburg.

“The Wabash-Erie Canal, the biggest financial fiasco in the state’s history, was the stimulus for Indiana’s ban against going in debt.

“The depot building stood for 135 years. In its later years it served as a reminder of the canal, to many, of the romantic and historic times.

“It was downed to make way for progress. Owners of the building, Wyatt-Rauch Farms Inc., had the building demolished in hopes of making the property more attractive to prospective land buyers. The building had been used by Wyatt Seed Co. for storage until Wyatt Seed Co. burned down in 1982. Since then Wyatt Seed Co. has moved south of town with its operations. Wyatt-Rauch Farms Inc. has had in mind trying to sell the property where the seed company stood.

“ ‘I hated to see it go…The Wabash-Erie Canal, you don’t see much of that around anymore, but the building wasn’t safe. It was a liability sitting there,’ said C. M. Brown of Wyatt Seed Co.

“A partner in Wyatt-Rauch Farms Inc., Russell Mahoney said renovation of the building was just not feasible, because of the high cost it would involve.

“The building was built in 1850, the same year cholera struck Pike County.”

Here, the article picks up the history by Ruth McClellan that was related in the 1975 article. At the end of the article it says, “Portions of the canal can still be seen near Glezen just off of state road 57 and county road 150 N. Another place to see the canal is on the north side of State Road 56 near the Bowman community.”

The old depot building and its importance to the Wabash and Erie Canal could have been forgotten in the following years. However, the Indiana Historical Bureau erected an Indiana State Format Marker on the North side of 108 W. Main Street in Petersburg, Pike County, Indiana in 1992. The marker stands in front of a fast food restaurant. The canal ran at the foot of the hill behind the restaurant.

Sail on Sail on and the Wabash Erie Canal

By Tom Castaldi

What do the words, “Sail on Sail on,” have to do with the Wabash & Erie Canal? Sailing congers up the image of boats on water moved gracefully by wind power. Early canal boats functioned just fine without a sail notably, but rather by the towing motion of horse or mule.

If you go on-line and word search, “Sail on Sail on” a couple of suggestions appear. One may be a song by the Beach Boys from their 1973 album Holland with the words “Sail On Sailor.” José Farmer included “Sail on! Sail on!” in an alternate history story he published in Startling Stories in 1952. Another, and perhaps the classic exhortation, is from Joaquin Miller’s poem Columbus. Found in the last line of the first four stanzas are the words, “sail on! sail on! and on!”

Historian Will Ball of the Cass County Indiana Historical Society was a prodigious writer of local history. In his “This Changing World” part 623 appearing in a September 1960, Logansport Press article, Ball describes a large Oak tree growing along the Wabash River. “No Doubt” he wrote, that “tall straight trunk was a sizeable sapling when Columbus bade his fearful mariners: ‘Sail on,’ as Joaquin Miller, the “Poet of the Sierras,” told so eloquently in his poem ‘Columbus.’ So who was Joaquin Miller, Christened Cincinnatus Hiner Miller? His parents Hulings and Margaret were living in Liberty, Indiana, when the infant first came into the world on March 10, 1839.

The family moved north in Indiana living in Randolph County from 1840 to 1842 where Hulings taught school. From 1842 to 1848 he continued to be employed as a teacher in Grant County. Finally he settled in Fulton County in 1848 where Will Ball made it known that “Joaquin Miller, who as a small boy (the youth Cincinnatus) used to come to Logansport with his father and brother, bringing loads of wheat from their farm home near Argos to the Wabash – Erie Canal here.”

Hulings Miller, gifted with an above average intelligence, was not satisfied with the status quo. He supported his family by teaching school and farming. Waldo Adams wrote in the 1964 Fulton County Historical Society Quarterly, “The farming operations seemed to be fairly successful for there was surplus corn. It was hauled to Logansport a distance of 30 miles. The cash corn market there was the only one for many miles around.” It was an important canal port where his harvest could find its way on board a canal freighter.

Before young Cincinnatus Miller was old enough for school, his teacher and father Hulings took him to observe classroom activities. Cincinnatus memorized much of what second and third readers were studying. Later, he became enthralled while listening to his father read the experiences of Captain John C. Fremont, a character who became young Miller’s idol.

When dogs were discovered to have decimated the family’s flock of sheep, Hugh McCulloch, representing the Miami people, determined the dogs that had done the damage were owned by the Miamis. Chief Mesh-ing-ome-sia insisted on paying for damages. With the money received from the sale of Grant County land the Hulings Miller family could achieve their dream of moving west to Oregon on March 17, 1852. Cincinnatus was age 13.

Once “Out West,” Cincinnatus went off to seek his fortune in the California gold fields. After that adventure he returned to college and studied in Oregon. Ultimately he succeeded in a career as a poet having received the moniker, “Poet of the Sierras” using the pen name Joaquin Miller. In addition to being poet and gold seeker, he was a cattle drover, teacher, lawyer, judge, newspaper editor and correspondent, and Pony Express rider. He died in 1913 and is buried in Oakland California.

It can be concluded that Joaquin Miller certainly “sailed on” successfully delivering his poetic words well after those days of hauling grain to a busy shipping port that was the Wabash – Erie Canal.

The Emita II Sold

Mid-Lakes Navigation of Skaneateles, New York has sold its 65-foot, 100-passenger “The Emita II” to Harbor Country Adventures of New Buffalo, Michigan. The Canal Society of Indiana had very enjoyable and informative overnight trips aboard the boat in October 2003 from Syracuse to Lockport, in August 2007 from Syracuse to Waterford, and in June 2014 from Lockport to Syracuse learning the history of the Erie Canal and its surrounding communities from Dan Wiles.

“The Emita II” was purchased by the Wiles family in 1974 from Casco Bay Lines in Portland, Maine. She ran overnight trips across New York state until she took over the daily sightseeing and dinner cruises from “City of Syracuse,” her sister vessel. She will now ply the waters of Lake Michigan under the same name according to her new owner Victor Tieri.

Teddy Roosevelt celebrated Erie Canal’s 100th Anniversary

Gib Young, aka Teddy Roosevelt, was featured at the 100th anniversary celebration of the New York State Canal System on May 10, 2018. Theodore Roosevelt was the governor of New York when the original barge canal opened. Many CSI members will remember his first person presentation of “Teddy” at our tour of the Whitewater Canal when he spoke at our banquet in the Sherman House in Batesville, Indiana on April 14, 2012. Gib is from Huntington, Indiana and portrays “Teddy” all around the United States. He can also be seen on the Whitewater Valley Railroad train at various times or at Mt. Rushmore with other first person presenters of Washington, Lincoln and Jefferson.

The ceremony, which was held at the East Guard Lock on Westmoreland Drive in Brighton, New York, included a reenactment of the first filling of the Erie canal one hundred years ago on May 10, 1918. A plaque was unveiled that designated the canal system a National Historic Landmark.

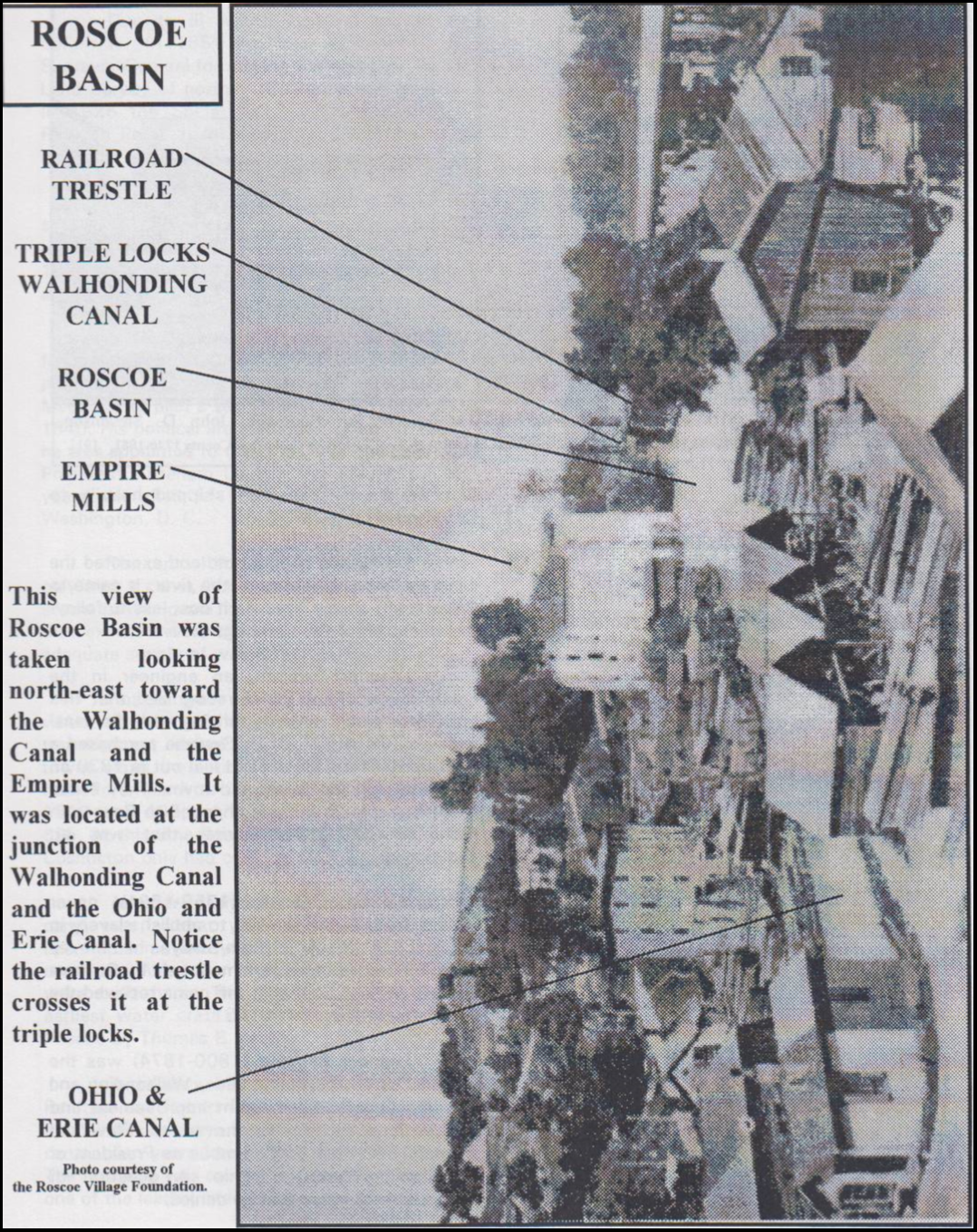

Removal of Walhonding River Dam

Six-Mile Dam, a low-head dam that was constructed in 1830 as part of the Walhonding Canal system and later served as a water source for a mill and plant in Roscoe until 1953, is to be removed from the Walhonding River to improve the habitat for fish and mussels. After the dam is removed some wing walls and lock chambers will be shored up to preserve some of the history of the dam. The estimated project cost is $1.8 million. Sport fishing should be improved, aquatic life enhanced, and an increase in the diversity of the area’s animals should be seen following the project.

Linn Loomis, Newcomerstown, OH

Contributions to CSI Archives

Linn Loomis, CSI member from Newcomerstown, Ohio has sent the following articles from the Coshocton Tribune:

Canal related

“State looking to remove dam on Walhonding River,” “New ice jam monitored on Muskingum River,” “Colorful figures and stories of the Ohio & Erie Canal,” “Born on a Canal Boat, Captain Pearl R. Nye (1872-1950),” “Lost drawings of the Ohio and Erie Canal surface after 190 years” (drawings actually of New York’s Erie Canal by John Henry Hopkins)

Company visited on early canal tour

“Longaberger comes home,” “Deal pending on Longaberger basket building,” “Mattress maker buys Longaberger properties,” “Basket building sale pays taxes, not Longaberger,” “Sale of Longaberger building finalized”

David and Marilyn Badger, from Polk, Ohio, have donated a copy of the booklet “Ohio’s Canals,” which was printed by the Allen County/Fort Wayne Public Library, to the CSI archives.

Sign Along Roadside

Recently the following sign was seen along the roadside: “Frog parking only. All others will be toad.” The frog is the mascot of the Canal Society of Indiana since frogs were in the canal during canal days and are still there today.

Canal Society of Ohio Spring Tour:

April 20 – 22, 2018 Ohio & Erie and Walhonding Canals, Roscoe Village, and Coshocton, Ohio

Text and photos by Sue Simerman

Friday was a beautiful day for a drive along the ridges, hills and valleys of Central Ohio to arrive at Coshocton. We headquartered at Coshocton Village Inn on N. Water St. across the river from Roscoe Village. This canal era attraction on the Ohio and Erie Canal was restored by Ed and Frances Montgomery. It

was inspired in part by Colonial Williamsburg.

We began with an evening meeting and slide presentation at the Johnson Humrickson Museum on Whitewoman Street. We had time to browse before the preview of the tour by Mary Starbuck and Friends.

Saturday morning saw our group watching for a large tour bus, but we saw two medium-sized, city-style buses with the words FUN BUS wrapped around their sides. The buses were comfortable with extra leg room.

Since the scheduled bus had broken down on Friday, we needed two leaders instead of our one prepared expert, Larry Turner. Luckily we had Terry Woods with us, a historian on canals, author and Honorary Trustee of CSO. Steve, my husband, and I were on the bus with Terry Woods and Mary Starbuck making a total of 16 passengers.

We started by driving east on Hwy. 36 along the swollen Tuscarawas River on our right. At Lewisville we made several turns and passed a trailer park to Canal Street where we could see the Ohio and Erie Canal prism and a ball field in a canal basin. Stacie Stein of Roscoe Village Visitor’s Center was with us. She said that the ball field was often wet and spongy.

Continuing on 36 E to Co. Rd. 105 we made a right turn, still having the river on the right. We saw one remaining wall of Lock 22, which had a lift of 7 feet. We drove through Newcomerstown, made note of some historic buildings, and then saw the familiar dip of canal in the back yards of homes. We learned that Lock 20 had been on the east side of town and that Cy Young, a famous baseball pitcher (1890-1911), had come from Newcomerstown.

We turned west back onto Hwy. 36 to the small town

of Orange on 751 close to Hwy. 36. We drove down a gravel dead end drive and disembarked to look at some stones that were the abutment remains of a one span aqueduct. We may have seen more if Evans Creek had not been at a level above normal. Locks 23 and 24 were basically lost to the construction of Hwy. 36.

Remaining on 36W we came to a lock that can be seen from the highway and is located where the railroad comes from the right and skims along the highway. We used township Rd. 508. Lock 25 (Wild Turkey Lock) is being maintained by the county parks and had a lift of 9 feet. Someone asked, “What is that onion smell?” We discovered a plant called Ramps, which can be used in cooking.

Lock 25 has one wall that is standing fairly straight and has alternating sizes of two different lengths of stone. The short ones may have been just as long as the others but were placed with the one end being part of the lock wall. To give added strength? Trees now grow in the chamber. It was holding water at the time we visited. The main wall was sinking some on the west end. Larry Turner said he thought the wall had been rebuilt.

We went back to Roscoe’s visitor center for a restroom break. As we left we turned right to see the lower canal basin that has been cut in half by Hwy. 36. The water level was up so we could not see the remaining cut-off wood pilings of the railroad trestle. This had been the Toledo, Walhonding Valley and Ohio Railroad.

The Triple Locks we saw were at the beginning of the Walhonding Canal. The volunteers at the visitors center have done an excellent job of having the landscaping ready for the spring visitors, even the Triple Locks (Locks 1, 2 and 3) have been improved and welcoming.

We then followed the Walhonding Canal west. We saw the canal prism on our left and learned that it was watered until the mid 70’s. Terry gave us some insight of his explorations in the 60’s and later.

We made a left turn on Rd. 1235 that was marked as a public river access. We reached the shore of the Walhonding River and could see across to a campground. We were above Six Mile Dam and saw an island to our left. The south end of the island has Lock 5. It can not be seen due to the overgrowth. The canal crossed the river here, but it is not known by which method. Michael Greenlee of the ODNR met us and explained the history of the area and the low head dam. It is settling on one side and some scouring is occurring. This dam is scheduled to be decommissioned in the fall of 2019. Although plans were not finalized, at the time the plan was to carefully tear it out, study it and save what they could. This would be done from wing wall to the opposite wing wall. It should improve the number of fish and mussels in the river and make it much easier for canoeists, who now have to portage. Some would like a park to be created with access to Lock 5.

On the highway again we drove through Warsaw still going west on 36. Looking down the sloping farm ground on our left we saw the Walhonding Canal being used for drainage. It was behind a farm house and several small buildings. By looking closely we saw the end stones of a lock and after passing the house we saw the opposite end with some small trees along its length. Our tour leaders tried to get the farmer to relent and let all of us on his property, but he was afraid that he would have arrowhead hunters walking in his fields. We were told that concrete had been poured as a floor for Lock 8 and that it was used as a corn crib.

On the highway again we drove through Warsaw still going west on 36. Looking down the sloping farm ground on our left we saw the Walhonding Canal being used for drainage. It was behind a farm house and several small buildings. By looking closely we saw the end stones of a lock and after passing the house we saw the opposite end with some small trees along its length. Our tour leaders tried to get the farmer to relent and let all of us on his property, but he was afraid that he would have arrowhead hunters walking in his fields. We were told that concrete had been poured as a floor for Lock 8 and that it was used as a corn crib.

We continued west and made a stop at the Mohawk Dam, dated 1935, which is operated by the Corps of Engineers. Robert Hawk gave us some history of the dam saying it is one of 5 to control flood waters for the Muskingum River Valley. We were allowed inside to see the controls for the 6 gates. We had lunch at Roberta’s in Warsaw. After lunch we had time to walk up the street to the Walhonding Valley Historical Museum. We were welcomed and shown their displays. Others walked in the other direction to look at a culvert.

Heading back to Roscoe we turned on Rd. 23 and made a stop on private property to walk to Crooked Run Culvert, which is still in use with solid construction on both sides. Some of us had a wobbly walk across the farm field with lots of glacial rocks.

We arrived back at Roscoe at 2:30 p.m. and some did the Roscoe Village mini tour. Others went back to the inn and took their cars to explore on their own.

The evening banquet was at the Event Center at the Visitor’s Center. The speaker was Michael Greenlee of the ODNR. He told us once again that mussels can not walk around the Six Mile Dam.

For those who would be interested in more extensive study of the Walhonding Canal, I would recommend Terry Woods book “Twenty Miles to Nowhere.” The canal began operation in 1842 and was abandoned to boat traffic in 1896.

Governor Samuel Bigger and His Canal Connection

Find-A-Grave # 11178

By Cynthia Powers

On June 28, 2018, an article by Kevin Leininger in the Fort Wayne News Sentinel called attention to a plan to upgrade the bridge on Lafayette Street that crosses the St. Marys River in Fort Wayne. I have crossed that bridge many times, but hadn’t known that it was named for former Governor Samuel Bigger.

I did know that Gov. Bigger’s grave is all by itself in McCulloch Park, just south of the former General Electric factory on Broadway Avenue. There is a story there: Broadway Cemetery was once at that location, but in the 1860s all the bodies were moved to the new Lindenwood Cemetery. However, no family members could be found to give permission to move Gov. Bigger. So he was left there; in 1994 GE donated a 6 ft. granite marker to replace a small plaque.

Samuel Bigger lived from 1802 to 1846. He was born in Franklin, Ohio, and studied law at Ohio University in Athens, Ohio. He had a law practice in Liberty, Indiana; he married Ellen Williamson. They had no children. (Maybe that’s why nobody could be found to authorize moving his grave to Lindenwood, although he did have a surviving brother.)

In 1835 Bigger was appointed as a judge on the Indiana Circuit Court, where he served during the time of the grandiose plan called the Mammoth Internal Improvement Act of 1836. The financial panic of 1837 devastated the state’s economy just when Indiana had taken on $10 million in debt on which the interest was $500,000.

Photo by Kristina Frazier-Henry

Bigger was nominated by the Whigs because he hadn’t had much to do with approving the Act, which tarnished the potential candidacy of the previous governor, David Wallace. Wallace was abandoned by the Whigs, who then nominated Bigger. Another advantage Bigger had when running was that he rode on the coattails of the presidential candidate, William Henry Harrison, “Old Tippecanoe.”

Bigger, a Whig, was governor between 1840 and 1843, dates of interest to canal enthusiasts. Bigger’s administration decided to prioritize the projects that would (they hoped) produce the most revenue, and thereby have the best chance of reducing the debt. Most likely to do that, they thought, would be to focus on the Wabash and Erie Canal.

That strategy worked, to a point. Indiana’s debt spiraled to about $15 million in interest and principal. He was able to cut the debt in half, to “only” about $9 million. But money – or lack of it – was still a big problem, and as all canallers know, Indiana was virtually bankrupt.

So Bigger had taken office when the interest on Indiana’s debt was ten times its annual income. A massive tax increase was proposed, as much as 300% in some areas. Many people refused to pay, and that idea was abandoned. Chaos ensued, among charges of widespread graft and corruption. Bigger withdrew from consideration for a second term, and he was succeeded by James Whitcomb, a Democrat. The financial situation was resolved in 1847 by the Butler Bill, which renegotiated the debt and established a separate trust.

A contemporary described Bigger thus: “He ever occupied a respectable plane, he never fell below it, and his altitude was never much above it.” He was “affable, honest, good-natured, steady” according to Paul Fatout in Indiana Canals.

According to Kevin Leininger’s article, the city of Fort Wayne plans an ornamental makeover of the bridge when it rebuilds the bridge’s deck in 2022. The southbound lane of U.S. 27, Clinton Street, crosses the St. Marys on the ornate Martin Luther King Jr. bridge, upgraded in 2012. When the upgrade is done, maybe we will notice the “better, Bigger Bridge” and think of his role in the canal era.

Delphi’s Canal Park Festival & Updates

From Dan McCain’s report and photos

Canal Days Festival was held in Canal Park in Delphi, Indiana on July 7 and 8, 2018 celebrating the completion of the Wabash & Erie Canal from Lafayette, Indiana to Toledo, Ohio, 175 years ago. At noon on July 7th a proclamation received from Wade Kapsukiewicz, Mayor of Toledo, honoring this canal milestone and the Grand Celebration that occurred at that time, was read from the front steps of the Reed Case House. When finally completed the canal extended 468 miles from Toledo to Evansville, Indiana.

Visitors to the park saw the newly restored 1880 Sleeth Post Office that had been completed through a grant from the Tippecanoe Arts Federation utilizing funding from North Central Health Services. Inside were several memorable items and furniture as well as actual mail boxes from another town’s post office that were found in an Antique Shop in Lafayette.

They also saw the Little Red Mill that was placed on a new foundation near the Canal Boat Warehouse. Carroll County Wabash & Erie Canal volunteers completed it by placing a water wheel and a mill race to direct water and operate the wheel.