Index:

William Nicholas Roberson

Find-A-Grave # 46003265

By Carolyn Schmidt

William Nicholas Roberson was born in Washington county near Jonesboro, Tennessee to David and Mary (Roberts) Roberson. He lived there for sixteen years and learned to read and write. He moved to Marion county, Indiana with his parents. His mother died shortly after coming to Indiana. He did not attend school the first year because there were few schools outside of Indianapolis. He worked on farms by the month receiving $8 per month and then got a sub-contract from the State of Indiana to dig a ditch. It took one summer to dig. His father died in 1832. Then he boarded with his brother for $1 per week and regularly attended school. After attending for two weeks he had made such rapid progress in his studies, especially in arithmetic, that he led the rest of the students. His teacher, Mr. Cook, said that in many years’ experience he had never seen William’s equal in figures.

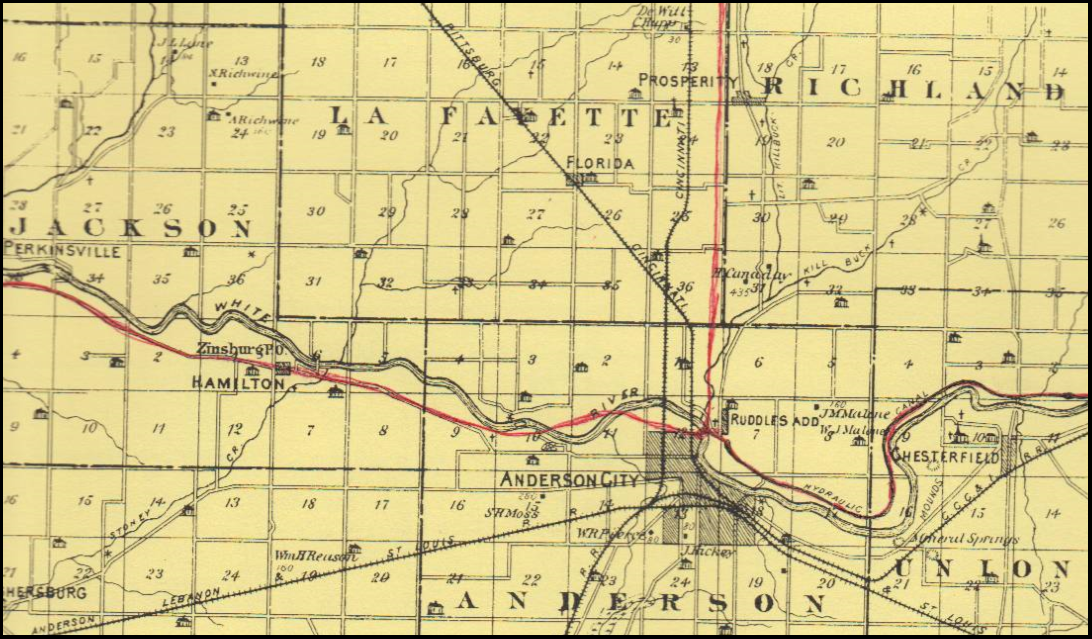

Unfortunately, William only managed to attend school a mere 24 days. He had to leave because he had signed another contract with the State to clear one-half mile of the northern section of the Central Canal that was being built in Madison county somewhere between Perkinsville and Anderson, Indiana (1836-39).

At the time of the vast Internal Improvements Bill, which was signed into law by Governor Noah Noble on January 27, 1836, the Central Canal was the longest of the canals planned to be built in Indiana. It was to run from its junction with the Wabash & Erie Canal at Peru, Indiana to the Ohio river at Evansville, Indiana.

There were three sections of the Canal. The northern section ran from Peru to Broad Ripple, the Indianapolis section from Broad Ripple to Port Royal (now Waverly, in Morgan County), and the southern from Port Royal to Evansville. Although contracts were let for all districts in all divisions, there was limited digging in the northern division and it was never completed. Remnants of the Central Canal can be found in Madison county from Alexandria to Anderson and from the feeder from Daleville (in Delaware county) to Anderson.

A contract for clearing involved cutting down all timber and brush on the right-of-way of the canal, removing all timber and brush, and digging out the tree stumps. In a Contract of Parties for the Wabash & Erie Canal, instruction is given to the contractor for clearing a section. This would be much the same for work done on the Central Canal.

“First, in all places where the natural surface of the earth is above the bottom of the canal, and where the line requires excavation, all trees, saplings, bushes, stumps and roots, shall be grubbed and dug up at least sixty ____feet wide; that is on the towing path side of the center, and ____ ____wide on the opposite side of the center of the canal, and, together with all logs, brush, and wood of every description, shall be removed at least twenty feet beyond the outward line of said grubbing on each side; and on the space of twenty feet on each side of said grubbing, all trees, saplings, bushes and stumps shall be cut down close to the ground, so that no part or any of them shall be left more than one foot in height above the natural surface of the earth, and shall, also, together with all logs, brush, and wood of every kind, be removed entirely from said space. And the trees, saplings, and bushes shall also be cut down, fifteen feet wide, on each side of said space so to be cleared, and also all trees which, in falling, will be liable to break or injure the banks of the canal; and wherever the situation shall be extended in breadth so far that no uncleared land may be occupied by the embankment or excavation. And no part of the trees, sapling, brush, stumps, wood, or rubbish of any kind, shall be felled, laid or deposited on either side of the sections adjoining this contract….”

After clearing the one-half mile in Madison county, William and Andrew Wilson repaired damages done by a storm on an arm of the Central Canal in Indianapolis. This took one summer. From the Central Canal contracts held in the Indiana State Archives, we know that A. (Andrew) Wilson held a contract for Section 23 and later held another contract for Section 18 in the Northern Division. It is likely that William worked on Section 23.

Photo by Frank Merriman

William, age 25, was married to Sarah Johnson, daughter of David Johnson, in 1841. They had four children, all of whom died young. Sarah’s birth and death dates are unknown. She was first buried in Greenlawn Cemetery. She then was reinterred in Row 2 Grave 2 in Floral Park Cemetery in Indianapolis, Indiana. The inscription on her tombstone says, Sarah, Consort of William N. Roberson.

William must have done very well with his work or received some inheritance from his parents, for he bought and resided on 80 acres in Belmont, now West Indianapolis. Four years later he bought 100 acres paying $15.50 per acre or $1,550.00 total. No improvements had been made to the land, which was covered with green timber. He erected a log cabin on this property and

resided in it for a year. It is likely he built a better home on this property for he was still living on it in 1893 according to Pictorial and Biographical Memoirs of Indianapolis and Marion County, Indiana. He lived on the farm until his death.

Andrew Wilson teamed up with William and they had 3 saw-mills in different parts of Marion county. William stayed in this business for 5 years before selling out and returning to his land. He immediately began clearing the timber and soon had sixty-five acres ready for cultivation. In 1852 he purchased 82 acres that adjoined his farm.

On November 11, 1852 William was married to Nancy Emeline Flanagan. He was 44 years old and she was 23. They had seven children. One of their children died at a young age.

In 1872, William bought 120 acres in Wayne township. In 1878 he bought another 80 acres that adjoined his farm. He also bought 146 acres in Morgan county.

In 1893, when William was 77 years of age, the Pictorial and Biographical Memoirs of Indianapolis and Marion County, Indiana said that William’s life had been one of honor and usefulness. He has “accumulated a fortune that enables him to enjoy most thoroughly the comforts and conveniences of life. In spite of his advanced years, Mr. Roberson still keeps up the active and industrious life that brought him in such substantial rewards, and may men much younger than he display less activity, mentally and physically, than does our worthy subject.”

Little did they know that William Nicholas Roberson would live until the ripe old age of 97. He passed away on October 28, 1913 and was laid to rest on October 30, 1913 in Lot. 472, Sec. 39 of Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis, Marion County, Indiana.

William’s second wife, Nancy Emeline Flanagan preceded him in death on January 27, 1913 at the age of 83-84. She was laid to rest on January 30, 1913 in Lot 472, Sec. 39 of Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis.

Crown Hill Cemetery, Indianapolis, Marion County, Indiana Photos by Rick France

William Nicholas Roberson’s Genealogy

Name Birth B. place Death D. place

Great Grandfather

Roberson, ? Scotland Highlands

Grandparents

Roberson, Charles 1765 TN 1863

m. ? , Polly

Parents and Siblings

Roberson, David 1785 Washington co, TN 1832 Marion co. IN

m. Roberts, Mary 1790 TN 1831

9 children of which 2 are unknown

Roberson, Charles 9-15-1808 12-10-1896 Marion co. IN

m. Johnson, Mary

8 children

Roberson, William N. 10-23-1816 Washington, TN 10-28-1913 Wayne twp, Marion co. IN

See chart below

Roberson, Sophia

m. Derringer, David

3 children

Roberson, Kesiah

m. Catterson, ?

Good sized family

Roberson, Sarah

m. Renison, William

1 son

Roberson Rose A.

m. Hatton, ?

2 children

Roberson, Maria

m. Sylvester, Gabriel

1 son

William Nicholas Roberson’s Wife, Children, Grandchildren

Roberson, William N. 10-23-1816 Washington, TN 10-28-1913 Wayne twp, Marion co. IN

m/consort Johnson, Sarah Floral Pk. Cem. Marion co. IN

(1841)

4 children, all died young

m. Flanagan, Nancy Emeline 1829 1-27-1913 Crown Hill Cem., Indianapolis, IN

(11-11-1852)

1 child of seven died young

Roberson, Louisa Ella 1856 Wayne twp. Marion Co. IN 1933

m. Kreitline, Charles

Kreitline, Charles

Kreitine, Louella

Roberson, James B. 1858 Wayne twp. Marion Co. IN 1941

m. Kempton, Ida

Roberson, Bessie

Roberson, Elsie

Roberson, William

Roberson, Joseph A. 8-19-1860 Wayne twp. Marion Co. IN 1939

m. Folz, Eva 1891

Roberson, Grace 1883

Roberson, Harry 1885

Roberson, Hazel 1890

m. Marshall, Nancy Lavada 1866 1946

(Sept. 16, 1896)

Roberson, Annie Bell 1862 Wayne twp. Marion Co. IN 1904 Indianapolis, Marion co. IN

m. DuBose, Clarence

DuBose, Gertrude

DuBose, Edith

Roberson, Nicholas 4-??-1863 Wayne twp. Marion Co. IN 1949

m. Pearson, Nancy

Roberson, Henry 5-??-1866 Wayne twp. Marion Co. IN 1947

m. Mann, Mand

Roberson, Mabel.

Sources:

Ancestry.com: Public Member Trees

Marshall, Pennington, Maxwell, Hilligas, Hastings, Lindsey, Fishel, Nugent, and others

Wagnor Family Tree

Find-A-Grave: William Nicholas Roberson #46003265

Sarah Roberson #5663568

Huppert, Charles B. “A Brief Commentary on the Central Canal.” Ft. Wayne, IN: Canal Society of Indiana, 1999.

Journal of the Senate of Indiana, During the Thirty-ninth Session of the General Assembly, Commencing Thursday, January 8, 1857. Indianapolis, IN: Joseph J. Bingham, State Printer, 1857.

Pictorial and Biographical Memoirs: Indianapolis and Marion County, Indiana. Chicago, IL: Goodspeed Brothers, Publishers, 1893.

- S. Federal Census: 1850, 1860, 1870, 1880, 1900, 1910

Old Van Wert & Wabash & Erie Canal Free Turnpike Pay Order Found

I hereby certify that Lyle Tate has performed labor on the Van Wert & W&E Canal Free Turnpike under my direction to the amount of Sixty dollars and Forty five cents which you will please pay him.

$60.45 Thomas Whelan

In this 1851 document, Thomas Whelan orders that Lyle Tate be paid $60.45 for his labor on the Van Wert & W&E Canal Free Turnpike.

An act to provide for laying out and establishing free turnpike roads in Ohio had been passed on March 12, 1845. Later, on March 20, 1851, another act was passed to incorporate the Putnam and Paulding Western Free Turnpike Road company by the General Assembly of Ohio. It appointed John Matson, Nathan Eaton and David Millinger commissioners to lay out and establish a free turnpike road, commencing at a point on the Lima and Defiance turnpike road, in section eighteen, town one north, range five east, and run west to the county line, eighty rods south of the north-east corner of section thirteen, town one north, range four east, in Paulding county; thence due west to intersect the road running from Van Wert to the Wabash and Erie Canal. Lyle Tate worked on the latter.

Died Aug. 10, 1890

Aged 70 Y. 3 M. 6 D.

Photo by PLS

Find-A-Grave 164154117

Tate’s Landing on the Wabash & Erie Canal in Emerald Township, Paulding, Ohio is named for canal worker Lyle Tate (May 4, 1820-August 10, 1890). Tate had bought up land around one of the locks. Sometimes this lock is called Reids after Captain Robert Reid (1827-1875), who established a post office and town with a grocery store and several taverns near it. It is also called Sharp’s Lock.

The lock at Tate’s Landing is Lock #9 in Ohio. It is thirteen miles from the Indiana/Ohio state line. It has a lift of 4 feet 9 inches.

During the Reservoir War a group of 200 local men, who were tired of the flooding when Six Mile Reservoir overflowed after the canal was shut down and a bill that they had proposed to fix the problem was not passed by the state legislature, joined forces to correct the problem. Known as the “Dynamiters,” they destroyed the bulkhead of Six Mile Reservoir and 3 locks. They also burned down the locktender’s house at Tate’s Landing. In 1900 they blew up the town’s saloon.

Tate is buried with relatives in Live Oak Cemetery on Emerald Road in Paulding.

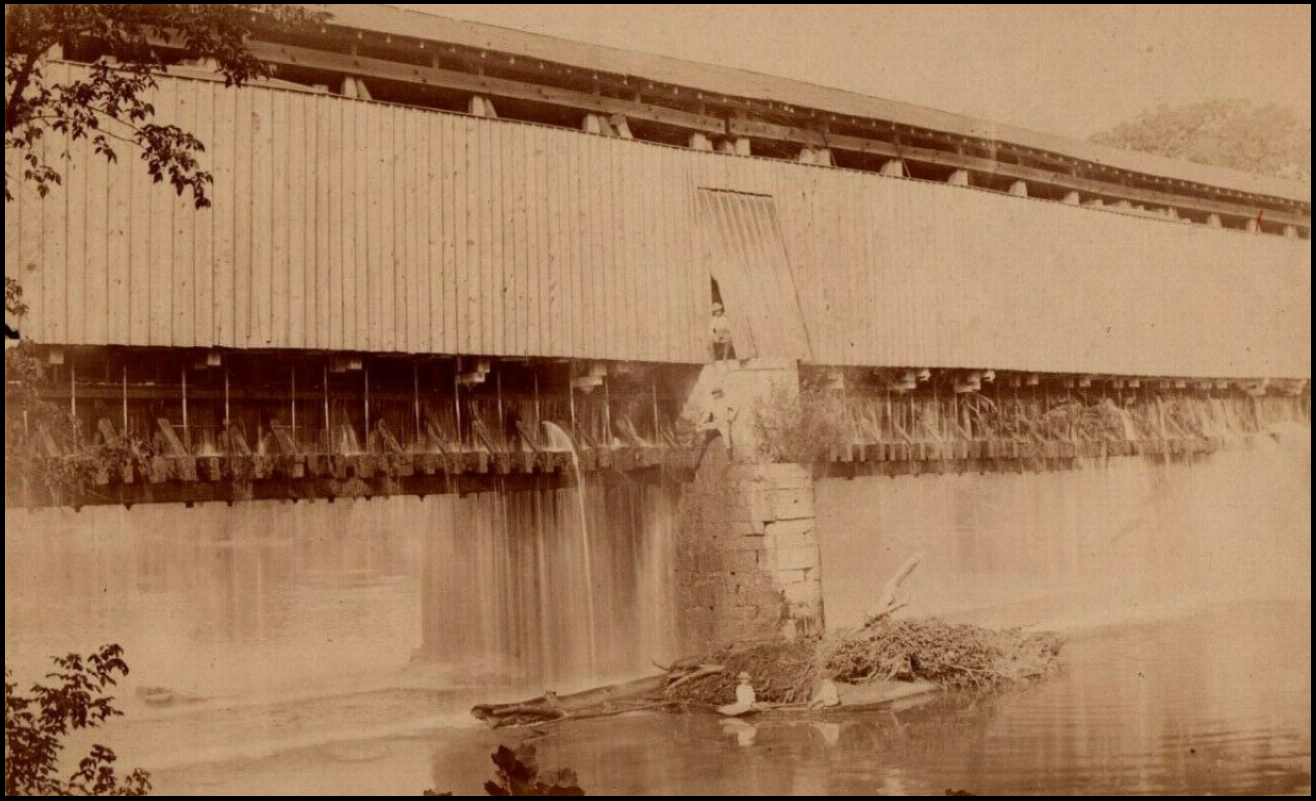

Neil Sowards, CSI member from Fort Wayne, Indiana, recently found this picture on E-bay. It shows the aqueduct that carried the Miami & Erie Canal across the Great Miami River near Dayton, Ohio, just above the Taylorsville Dam in Wayne township. Note the two people up on the pier and the two people at the base of the pier. This covered bridge style aqueduct is similar to the one that carried the Wabash & Erie Canal over the St. Marys River in Fort Wayne, Indiana. The Miami & Erie aqueduct collapsed in 1903. The collapsing St. Marys aqueduct is seen in this picture beside the railroad bridge in Fort Wayne.

The St. Marys aqueduct was designed by Jesse Lynch Williams. Its construction began in 1834 under the direction of contractor Henry Lotz, who would later become mayor of Fort Wayne from 1843-44. The aqueduct consisted of a 160 ft. long wooden flume supported by a stone pier in the middle of the river and stone abutments on either bank. The flume was 17 ft. wide and carried about a six foot depth of water. The entire structure was built with covered sides and a roof, which gave it the appearance of a covered bridge. It weighed more than 450 tons. Water passed through the flume at about 5 miles per hour.

At the end of the canal era, the weathering by freezing and thawing took their toll on the aqueduct and it fell into decay. The Wabash & Erie Canal was sold in 1876. Later the Nickel Plate Railroad bought the structure in 1881. Its final demise came in 1883 when the old aqueduct was completely removed. Only portions of the stone abutments remain.

Article from Neil Sowards

Penalties for Destroying or Obstructing Indiana’s Canals

From The Revised Statutes of the State of Indiana, Adopted and Enacted by the General Assembly at Their Twenty-second Session,

Indianapolis, In: Douglas & Noel, Printers, 1838.

An act was approved on February 19, 1838, by the General Assembly of Indiana for the protection of the Canals belonging to the State, the collection of tolls thereon, and for other purposes. Below we present only the first part of the act regarding the destroying or obstructing of the canals. (The spelling has not been corrected.)

Sec. 1. Be it enacted by the General Assembly of the state of Indiana, That if any person or persons shall willfully and maliciously break, throw down, injure, or destroy any embankment, waste weir, lock, aqueduct, culvert, lock gate, or bridge, on any canal owned by the state, such person or persons, for every such offence, shall upon conviction thereof, by presentment or indictment before the proper tribunal, be sentenced to imprisonment at hard labor in the state prison, for any length of time; not less than six months, nor more than two years; and shall further be held liable to pay all damages, sustained by the state, in consequence of such offence.

Sec. 1. Be it enacted by the General Assembly of the state of Indiana, That if any person or persons shall willfully and maliciously break, throw down, injure, or destroy any embankment, waste weir, lock, aqueduct, culvert, lock gate, or bridge, on any canal owned by the state, such person or persons, for every such offence, shall upon conviction thereof, by presentment or indictment before the proper tribunal, be sentenced to imprisonment at hard labor in the state prison, for any length of time; not less than six months, nor more than two years; and shall further be held liable to pay all damages, sustained by the state, in consequence of such offence.

Sec. 2. That if any person or persons shall wantonly or unnecessarily, open or shut, or cause to be opened or shut, any lock gate, or any paddle gate, or culvert gate thereof, or any waste gate, or drive any spike, nail, pin, or wedge, into either of said gates, or shall in any manner interfere with the free use of said gates, such person or persons for every such offence, shall forfeit and pay to the state one hundred dollars, together with all damages consequent upon such offence, recoverable by action of debt, in the name of the state of Indiana, before any court having competent jurisdiction thereof.

Sec. 3. That every person—who shall lead, ride, or drive or cause to be led, rode, or drove, any horse, ox, or other animal, drawing after it any wagon, cart, dray, or other carriage, upon the towing path or berm bank of any of the canals of the state, shall for every such offence forfeit and pay to the state the sum of fifteen dollars, recoverable by action of debt as aforesaid.

Sec. 4. That if any person shall obstruct the navigation of any of the canals of the state, by sinking therein any stone, timber, vessel, or other thing, or by placing any obstruction on the towing path thereof, such person for every such offence, upon conviction thereof, shall forfeit and pay to the state; the sum of twenty-five dollars, together with the expense of removing such obstruction, recoverable by action of debt aforesaid.

Sec. 5. That if any boat or other float shall be so moored, on any of the canals, as to obstruct the navigation thereof, or if any person or persons shall obstruct the passage of boats on any canal by improperly stopping, loading, unloading, or otherwise mis-conducting any boat or other craft, and shall refuse or neglect to remove such obstruction immediately on being required to do so, by any officer on the canal, or by any person incommoded by such obstruction, the boatman or person who caused the obstruction shall forfeit and pay to the state, the sum of twenty-five dollars, recoverable by action of debt as aforesaid.

Sec. 6. That no person shall construct any wharf, basin, or watering place, on any canal of this state, or make any device or arrangement, which will draw therefrom any water, without first obtaining the consent in writing of the acting commissioner or principal engineer of such canal; and if any person shall violate this provision, by commencing the construction of any such device without the permission as before provided, or shall refuse to follow the directions of the acting commissioner or engineer, which may be given in regard to the location, size, and form of such wharf, basin, watering place, or other device as aforesaid, such person for every such offence, shall forfeit and pay to the state, the sum of fifty dollars, recoverable by action or debt as aforesaid; and the said acting commissioner or engineer, or any superintendent, or agent of the state, is hereby authorized to remove and destroy every such wharf, watering place, or other such device as aforesaid, at the expense of the person or persons thus attempting without permission to build it.

Sec. 7. That any individual may build a bridge across any canal of this state; Provided, the centre span of such bridge shall conform to the following specifications, to-wit: the underside of the bridge timbers shall be at least ten feet above the top water line of the canal, when the water is at its greatest height, and the string pieces shall be twelve inches deep at the ends, and twenty inches deep in the centre, to prevent them from swagging down toward the canal. The trussell or abutment which stands in the canal, shall be so placed as to leave thirty-one feet clear width for the passage or boats between said trussell or abutment, and the edge of the water when the canal is full, for a towing path; which towing path shall be excavated down to the level of six inches above top water line, so as to allow the horse and driver to pass under the bridge; and from the end of said trussell or abutment, the towing path shall be sloped at the rate of one to six; to the height of the adjoining tow-path; and to prevent the towing path from being undermined and rendered impassable by the action of the water route, a wharf shall be constructed in front, formed of two sticks of timber forty feet long; secured by square ties, the measurements and leveling herein required, to be made by the engineer having charge of the line, who shall attend to this duty whenever requested to do so by any individual, and if any person shall commence the construction of any bridge, which does not conform in every respect to the specifications herein given, such person shall upon conviction thereof, before any court having competent jurisdiction, forfeit and pay to the state the sum of fifty dollars, recoverable by action of debt in the name of the state.

Dredging Indiana’s Central Canal

By Carolyn Schmidt

During the canal era Indiana’s canals had to be dredged to keep them deep and wide enough to pass canal boats. Dredges similar to the one pictured above were used.

Today Indiana uses modern equipment to keep its canals clean. The Whitewater Canal silts up very easily. Then it has to be drained and cleaned out by Jay Dishman and his crew at the State Historic Site in Metamora. The depth of silt, etc. that accumulates over the years in Metamora, is seen in the following picture taken by Bob Schmidt in July 1998. which shows two young girls playing in the mud before the canal was dredged.

This year the heavy rains and flood waters washed away much of the mud. Jay Dishman reported that the Duck Creek Aqueduct was not damaged and that his crew may not have to dredge the canal in Metamora this year for the “Ben Franklin III,” the site’s canal boat, to run. He said the Laurel Feeder Dam area was another matter.

This year the heavy rains and flood waters washed away much of the mud. Jay Dishman reported that the Duck Creek Aqueduct was not damaged and that his crew may not have to dredge the canal in Metamora this year for the “Ben Franklin III,” the site’s canal boat, to run. He said the Laurel Feeder Dam area was another matter.

The Whitewater Canal has its historic canal bed. This is not the case of the Central Canal in downtown Indianapolis. There the canal bed has been concreted with sidewalks and exhibits along its sides. However, it still fills up from fish “poop,” decaying algae, and grass. In November 2018 this portion of the canal was drained and about 500 fish were removed. That was much lower than the 9,000 fish removed and released into the White River and a private pond for an earlier dredging project in 2007.

An article in the Indianapolis Star on December 15, 2018 said that native fish get into the canal from birds of prey unwittingly carrying fish eggs on their bodies. “The non-native species such as koi and goldfish are most likely deposited by sneaky pet owners.”

Once the Central Canal was drained, a wallet containing cash, a bowling ball, and a few Bird and Lime scooters were found. They tried to located the wallet’s owner.

Photo by Michelle Pemberton/IndyStar

Merrell Bros. of Kokomo was given the contract to remove over 250,000 gallons of sediment and organic growth by the Department of Metropolitan Development, which owns and maintains the canal from West Street to 11th Street in Indianapolis. Trucks and heavy machinery were used to scoop up the half frozen sludge. It was collected in “one spot, then loaded into tankers and transported to a processing facility in Speedway, Indiana. There, the water was removed from the material and sent to a waste water treatment plant. The leftover solids went into an area landfill,” according to the news article.

The cleanup price tag was estimated at over $547,320. Indianapolis picked up the majority of the tab with White River State Park covering some of the remaining cost.

Once the project was completed in May the Central Canal was beautiful once again. Take an opportunity to visit and stroll along it.

Wabash and Erie Canal, Two Documents

By Neil Sowards

I was thinning out my collection of documents and sold these recently on E-bay.

- Engineers verification of work done. It reads, “Logansport, July 7, 1838, I certify that work has been preformed on Section No. 148 of the Wabash and Erie Canal, Brady & Armitage Contractors, to the value of Eight hundred & forty eight Dollars Cents, in addition to the some previously certified, estimated agreeable to the terms of the contract. Present estimate, $848, Former estimates, $9112, Total $9960, A. David Engineer.” Wabash and Erie Canal vertical on left end. 2 3/8 by 5 1/8 inches. On back, “Registered, A Davis Engr.”

- Sight draft (Check). It reads, “WABASH & ERIE CANAL., $760. Logansport, July 7, 1838, Canal Fund Commissioners, at sight pay to Brady and Armitage or order Seven hundred & sixty Dollars Cents, for work done on Section 148 Wabash and Erie Canal as per estimate of A David Engineer, bearing even date and number herewith. Former Est. $9113, Present $848, Total $9960. Paid on for est. $8375, Present 760, Total $9135. J. N. Johnson, Acting Commissioner.” 3 1/2 by 5 5/8 inches. Signed on back, “B. R. Veep, For Armitage & Brady, Condit my account, H. McColloch, Cash.”

These verification and checks are very common for Ohio but this is the only one I’ve seen for Indiana.

The canals in Indiana were divided up into mile long sections and each section was bid on and contracts awarded to the lowest bidder. Money was scarce so no contractor had enough money to finance their section. So when they got some work done, the Residential Engineer inspected it and issued a certificate stating how much work had been done so they could be paid for it. Although certified as having done $848 worth of work, the contractor was only paid $760. That gave the contractor incentive to complete the contract. When all the work was done, the contractor did receive pay for all he had done.

The Wabash and Erie Canal ran from Toledo to Junction, Ohio to Fort Wayne. Then it went across the portage to the Wabash River and down it to Terre Haute. Then it went cross country and was to join with the Central Canal, which was never completed. The Wabash and Erie was completed to Evansville–the longest canal in America at 468 miles.

The Unique Waterway Alongside Delphi’s Canal Park

By Dan McCain

Mother Nature had a bigger impact on the creation of the canal channel beside the Canal Center in Delphi than man did. This waterway was carved out long before the Wabash & Erie Canal was created in the 1830s and 40s as a transportation route. This first “sluice” was carved in the earth 12-15,000 years ago.

The Late Wisconsin Glacier and its receding ice cap allowed a tremendous volume of water to flow in the Wabash waterway – enough to fill the miles wide valley. Evidence of that are the gravel deposits high up on the valley margins and huge rounded boulders that were dancing along the valley floor as the swift current flushed everything in its path.

The Late Wisconsin Glacier and its receding ice cap allowed a tremendous volume of water to flow in the Wabash waterway – enough to fill the miles wide valley. Evidence of that are the gravel deposits high up on the valley margins and huge rounded boulders that were dancing along the valley floor as the swift current flushed everything in its path.

This section now known as the canal bed was at one time a flowing “finger” of the pro-historic flush from the melting glacier. Because this area is buffered underneath by an even earlier rugged ocean reef (limestone bedrock) it resisted these erosive flows except for the enormous flush through this zone. Perhaps there were cracks in the bedrock that enlarged to create this finger of the Wabash.

Anyway, the remnant of this vast flow and streambed in the limestone was known in the 1830s as the “Bayou of Delphi.” It was a stagnant wetland with no flow except when the Wabash flooded. Whenever the river did flood through Delphi the adjacent lowlands were also flooded. Canal planners with a good understanding of water dynamics made this unique canal section through here by recreating this higher prehistoric level of the river. Higher level of flow would cause the bayou to become the actual canal channel.

Anyway, the remnant of this vast flow and streambed in the limestone was known in the 1830s as the “Bayou of Delphi.” It was a stagnant wetland with no flow except when the Wabash flooded. Whenever the river did flood through Delphi the adjacent lowlands were also flooded. Canal planners with a good understanding of water dynamics made this unique canal section through here by recreating this higher prehistoric level of the river. Higher level of flow would cause the bayou to become the actual canal channel.

So, the creation of a 12-foot high dam on the Wabash at Pittsburg helped in two major ways: one, it provided a six-mile-long lake that extended up past the early town of Carrollton where the canal boats could cross; and two, it created a sizable source of water to feed the canal all the way southwest to Lafayette and beyond. It filled the bayou to an adequate height to float the barges on through to Lafayette.

The abundance of flow also allowed Delphi and Pittsburg to have industrial uses of the water to power mills. Pittsburg was truly a mill town at the headwaters of navigation for steamship traffic and was accessed by canal boats as well. Shipping businesses boomed in the river town during the heyday of the canal. Though there was a steamship lock in the dam for upstream navigation to Logansport it was only used once. That time however was a failure because of the outcropping rock ledges on up to Logansport.

After the Pittsburg canal dam was blown out by vigilantes in 1881 the lake behind the dam returned to its former flowing “river” and the canal was abruptly left without a supply of water. It became the Bayou of Delphi again and appeared ugly and stagnant. Most people of Delphi disliked the canal. Children were told to never play down by the canal because they thought of “rats, snakes and dirty water”—the canal was taboo.

Not until the 1990s did the canal get cleaned up, dredged and rewatered. The industrious group of volunteers comprising the Wabash & Erie Canal Association has turned this “eyesore” into a marvelous recreational waterway with trails bordering the original towpath that are used by kids, families, dogs and hikers all enjoying these resources.

There are now ten miles of trails and three miles of canal owned and operated by the Canal Association and City of Delphi for the enjoyment of all who come to this little canal town in Carroll County.

Whitewater Canal Byway Association’s Old Depot Flooded

In the 1840s & 50s Spring freshets often hit Indiana’s Whitewater Canal and damaged many of its canal structures. Unfortunately flooding reoccurred in Metamora agaim this year. This time it flooded the campground and then entered the old railroad depot being used as the banquet facility for the Whitewater Canal Byway. With almost 18 inches of water on the lower level, the old furnace, air conditioner, and lower drywall were completely destroyed. This elevation was supposed to be above the 100 year flood level as provided by the Corps of Engineers. This loss of property was not insured.

Luckily the flood came at a time when locals were able to rescue the new tables and chairs that are used for the meetings and banquets held in the old depot. Also damaged was the permanent cabinetry in the kitchen and the carpets. Two separate Stanley Steamer companies worked for hours to remove about 1/2 inch of mud after the flood waters receded. The basic cleanup will be handled by local volunteers, but to restore the heating and AC systems, carpet and building structure it is estimated to cost more than $25,000. I have attached a photo looking East from the museum, which luckily was not damaged, toward the railroad depot building.

Candy Yurcak explained the Whitewater Canal Byway Association’s (WCBA) restoration plans. The heating and AC will be elevated above the floor level and some other measures taken to keep such a disaster from impacting the building itself. They are conducting fund raising dinners and events. One of the groups that annually uses the campground plans to donate funds from their next encampment to the Byway project.

The WCBA has been instrumental in raising the awareness of the canal and many other historic areas in the Whitewater valley. I challenge all of our CSI members to help this restoration project with their financial support. Any size gift would be greatly appreciated. The Byway is a 501 (c) (3) not for profit organization. Its Federal ID # is 26-1395588

Please send your check to WCBA, PO Box 75, Metamora, IN 47030. Be sure and identify

your gift as being from a CSI member. Hopefully we can raise a substantial amount to show our continuing support of their efforts.

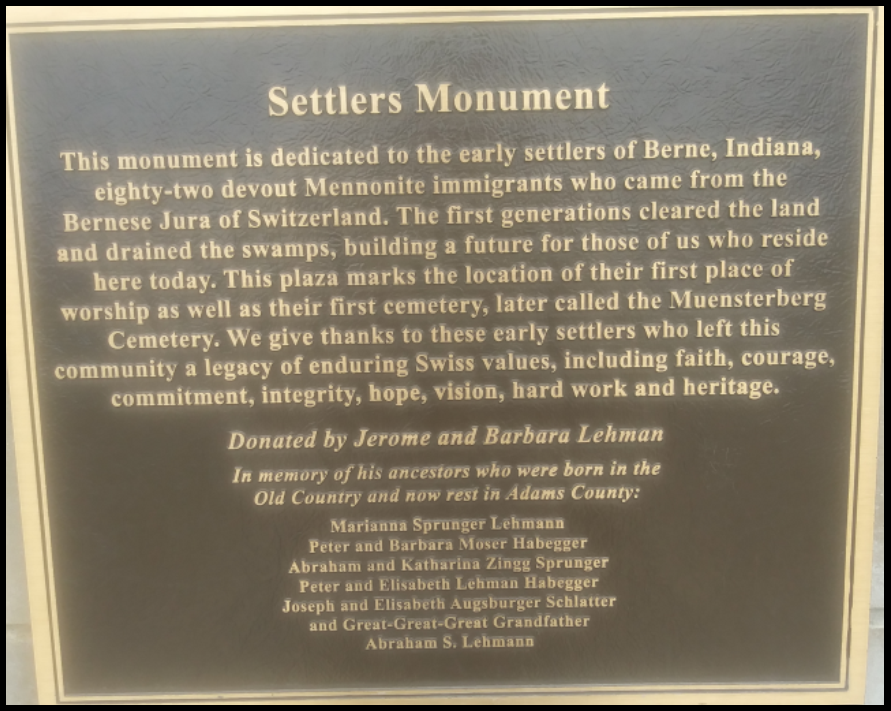

In Memoriam: Jerome W. Lehman

Jerome (Jerry) W. Lehman, past CSI director and life member, passed away on April 1, 2019 at Terre Haute Regional Hospital in Terre Haute, Indiana. He was 82 years old.

Jerry was born on April 28, 1936 to Lewellyn and Florence (Graber) Lehman. He was reared on a 100 acre farm near Berne, Indiana. It bordered nearly one mile along the Wabash River where he spent his spare time hunting and fishing.

He served in the United States Army in 1962, stationed in Italy. After returning from service he started an electronics service company and was a subcontractor to Motorola for 35 years servicing 2-way radio systems. At it’s peak he owned Motorola Service Stations in Terre Haute, Bloomington, Vincennes and Evansville and had 23 employees.

After retirement he became interested in growing, hybridizing and sharing his knowledge of persimmons and pawpaws. In 1991 he traveled to the Soviet Union on a horticultural exchange agreement for three weeks and since then has exchanged persimmon and pawpaw with many Eastern European countries. He was invited and traveled in the fall of 2011 to Yalta, Ukraine to give a presentation on the American Persimmon and Pawpaw in the U.S. He became well known for his huge pawpaws and even had a variety of them named for him. Growers from all over the world visited his persimmon research ranch and pawpaw farm. He won prizes for his products, spoke around the world about them, shipped hundreds of pounds of pawpaw seeds to China, and sold pawpaws to micro-breweries for making beer. Recently, while pruning his trees, he fell and broke his back in several places. Complications eventually led to his death.

Jerry was a member of the Indiana Nut and Fruit Growers Association and the Northern Nut Growers Association for many years. He edited their publication for a while. He was also a member, director, and volunteer photographer for the Honey Creek Fire Department in Terre Haute.

As a member of the Canal Society of Indiana he served on the board of directors from 2013-2018. He attended many CSI tours. On one he spoke about he and his wife’s trip on the Amazon river and growing pawpaws. He brought fruit samples on other tours to share with members, took photos of tour sites and, with his wife, hosted a CSI board meeting in Terre Haute’s library.

Jerry is survived by his wife of 40 years, Barbara L. (Sweetenam) Lehman; children, Charles Lehman, Mark Lehman (A.J.), Jennifer Lehman and Cynthia Carnes; four grandchildren; eight great-grandchildren; and sisters, Marilyn Spurgeon (Charles), Norma Brandenburg (Ralph) and Elaine Mikesell (Garry). He was preceded in death by his parents.

Photos by Bob Schmidt

Settlers Monument

This monument is dedicated to the early settlers of Berne, Indiana, 82 devout Mennonite immigrants who came from the Burnese Jura of Switzerland. The first generations cleared the land and drained the swamps, building a future for those who reside here today. This plaza marks the location of their first place of Worship as well as their first cemetery, later called Muensterberg Cemetery. We give thanks to those early settlers who left this community a legacy of enduring Swiss values, including faith, courage, commitment, integrity, hope, vision, hard work and heritage.

Donated by Jerome and Barbara Lehman

In memory of his ancestors who were born in the Old Country and now rest in Adams County:

Mariana Sprunger Lehmann

Peter and Barbara Moser Habegger

Abraham and Katarina Zingg Sprunger

Peter and Elizabeth Sprunger Habegger

Joseph and Elizabeth Augsburger Schlatter

And Great-Great-Great Grandfather

Abraham S. Lehmann

Jerry and Barbara honored his ancestors by donating the Settlers Monument of a man, woman and child that was placed in Tower Plaza in Berne, Indiana. Its plaque reads:

Funeral services were held at the DeBaun Springhill Chapel in Terre Haute at 7 p.m. on Thursday April 4, 2019. A graveside service was held at the Mennonite Reformed Evangelical (M.R.E.) Cemetery in Berne, Indiana at 2 p.m. on April 5, 2019.

Memorials were to be sent to a charity of your choice.

Restoring Old Bridges for Canal Trails in Delphi

By Dan McCain, President CCW&ECA

Volunteers with the Carroll County Wabash & Erie Canal Association got involved in restoring old bridges when our emerging trail system began in the late 1980s and needed a bridge to cross the canal. To get us started I made an alliance with a retired liberal-arts college history professor from 75 miles away. He really was more of a structural engineer in his heart. We bonded and he started taking me along on some speaking engagements to historical organizations, etc.

I liked his take on the beauty and artistry of many of the old spans. He had written two books highlighting his inventory of hundreds of Indiana bridges—mostly from 1870s through 1930s. I was intrigued with his findings.

He led me to one of those he had inventoried within 15 miles of Delphi’s Canal Park. It was abandoned. The land and bridge had been turned back to the farmer/landowner. Once I saw it I knew we needed it for our trail crossing. It was an 1873 wrought iron “bowstring” arch.

The professor knew our volunteer construction crew at the Canal had talent to do some of the basic restoration steps but likely lacked the knowledge of metal restoration – especially wrought iron restoration. He introduced me to a vocational training specialist from Central Michigan and that got us all enthused.

The specialist was semi-retired and came to Delphi with his wife to spend a couple days every couple months. We learned about the properties of wrought iron and how to straighten and repair. And we learned something special – How to HOT RIVET metal parts together.

The restoration of our first span was in 1998-99 and is called the RED BRIDGE. Our Canal Boat goes under it on cruises.

The restoration of our first span was in 1998-99 and is called the RED BRIDGE. Our Canal Boat goes under it on cruises.

Then we got more bold and searched for another very special bridge. The professor knew of a Stearns Truss that was abandoned 60 miles north of Delphi. It became the BLUE BRIDGE for a trail over the canal in 2006.

And then we needed a wider bridge to cross the canal in Canal Park. We found a 132 foot iron span that needed straightening and riveting but would be taken apart for us by INDOT’s contractor, who was replacing this bridge with a concrete beam new span. This span is known as the GRAY BRIDGE in Canal Park.

Although the third bridge was bigger than anything we had done before, we learned how to handle larger pieces for repairs, painting and completing. Due to its size, this project was more expensive. We were fortunate to get two grants and donations to raise the $175,000 needed to cover costs.

Although the third bridge was bigger than anything we had done before, we learned how to handle larger pieces for repairs, painting and completing. Due to its size, this project was more expensive. We were fortunate to get two grants and donations to raise the $175,000 needed to cover costs.

All three of these bridges were completed primarily by our volunteer workers with hiring crane operators to do the things we couldn’t handle. Comparing our costs to what is often quoted for costs of restoration where the work is all done by professional contractors seems that we get our bridges finished for 20-30 percent of those costs.

The last historic bridge the Canal volunteers took on was to replace a section of our Monon Trail where INDOT severed the trail in building a new four lane super highway. We had held INDOT’s feet to the fire with insistence that there must be a crossing to keep our rail trial intact.

The last historic bridge the Canal volunteers took on was to replace a section of our Monon Trail where INDOT severed the trail in building a new four lane super highway. We had held INDOT’s feet to the fire with insistence that there must be a crossing to keep our rail trial intact.

We won this argument to create a bridge span but the caveat was that we “had to locate and acquire a bridge to suite our needs.” We went back to our history professor—the one that found our first three iron spans. He knew of this long special span that had been over the White River southwest of Indianapolis.

This bridge was the longest at 300 feet (to cross the four lanes). It was owned by Conner Prairie, a historical organization near Indianapolis that had removed the bridge from Freedom, Indiana and held it until they realized is wasn’t possible to put it across the White River. It was donated to us!

INDOT contracted to do the work of restoration, assembly and installation, which was a blessing because our volunteers didn’t have any business placing a 300 foot bridge across a four lane highway. It became known as the FREEDOM BRIDGE. It is a glorious gateway to Delphi unlike the multitude of modern concrete beam bridges on Interstates everywhere.

INDOT contracted to do the work of restoration, assembly and installation, which was a blessing because our volunteers didn’t have any business placing a 300 foot bridge across a four lane highway. It became known as the FREEDOM BRIDGE. It is a glorious gateway to Delphi unlike the multitude of modern concrete beam bridges on Interstates everywhere.

Throughout our restoration efforts other specialists became Canal volunteers like the history professor and the metal restoration specialist. Even a retired professional mason from 75 miles away taught us how to lay stone to face our bridge piers.

Abe Lincoln Featured at Annual Meeting

Carroll County Wabash & Erie Canal Association’s annual meeting was held on Tuesday, April 16, 2019 at the Canal Interpretive Center in Delphi. Its featured speaker was Danny Russell, who portrayed Abraham Lincoln. He told an adventurous story in first-person with Lincoln traveling from a log cabin to the White House and portrayed Lincoln with hilarity, heartbreak and humanity. They heard about his Indiana boyhood years (age 7-12) prior to his success as a prairie lawyer, through his political aspirations, the Lincoln-Douglas debates, Civil War tragedy and triumph, brilliant speeches, freedom for slaves, and much more. Lincoln’s clarion call was “All men are created equal.”

Carroll County Wabash & Erie Canal Association’s annual meeting was held on Tuesday, April 16, 2019 at the Canal Interpretive Center in Delphi. Its featured speaker was Danny Russell, who portrayed Abraham Lincoln. He told an adventurous story in first-person with Lincoln traveling from a log cabin to the White House and portrayed Lincoln with hilarity, heartbreak and humanity. They heard about his Indiana boyhood years (age 7-12) prior to his success as a prairie lawyer, through his political aspirations, the Lincoln-Douglas debates, Civil War tragedy and triumph, brilliant speeches, freedom for slaves, and much more. Lincoln’s clarion call was “All men are created equal.”

Earth Day Celebrated in Canal Park

Canal Park in Delphi observed Earth Day on April 20, 2019 by holding a “spring cleaning” of the park, its flower beds, gardens and trails. Over the years the day has become to be known as Project W.E.E.D. —Wabash & Erie Earth Day. Fifty to seventy five people come together every year from groups like Scouts, 4-H, and churches along with many individuals. They meet at Canal Park between 8-9 a.m. to receive instructions and assemble into teams. From there, teams are disbursed with a leader to work on a specific site. Some sites require driving to them, but everyone returns to Canal Park for lunch prepared by the local Psi Iota Xi sorority.

Canal Park in Delphi observed Earth Day on April 20, 2019 by holding a “spring cleaning” of the park, its flower beds, gardens and trails. Over the years the day has become to be known as Project W.E.E.D. —Wabash & Erie Earth Day. Fifty to seventy five people come together every year from groups like Scouts, 4-H, and churches along with many individuals. They meet at Canal Park between 8-9 a.m. to receive instructions and assemble into teams. From there, teams are disbursed with a leader to work on a specific site. Some sites require driving to them, but everyone returns to Canal Park for lunch prepared by the local Psi Iota Xi sorority.

Volunteers mark their tools with their names and dress appropriately with long pants, work clothes, work shoes, gloves and other protective wear. Jobs include grooming, de-brushing, landscaping, pruning, raking, bagging and even work with chain saws.

Dillow Robinson Tells About Canal Maintenance

By Terry Woods

Terry, the past president of the American Canal Society and the Canal Society of Ohio, visited and recorded interviews with canal people. Here is one with James Dillow Robinson, who though not actually a boatman, (he moved onto a State Boat with his Mother and Step Dad, Captain, in 1905 and became one of the crew in 1912), came back to work on the Ohio and Erie Canal for the Steel Company in 1921. Dillow knew a great deal about the later days of the canal, particularly those after the 1913 flood. Note that Indiana’s canal era ended about 1870, but Ohio’s continued until the flood. Indiana probably used similar ways to maintain her canals.

“From 1921 to 1924 I worked for American Steel & Wire Company1 for Engineer Howard Klepinger. He was in charge of all their property and the Ohio (& Erie) Canal from the pump house (at the works at EAST 49TH Street in Cuyahoga Heights) south to the Pinery Dam and feeder on the Cuyahoga River near Station Road, off Route 82 in Brecksville.

“Mr. Klepinger was the last engineer on the canal for the State of Ohio and had gone to work for American Steel and Wire after the State stopped maintaining the canal.

“There were three of us who worked for him, We had a truck, but no boat, only a scow pulled by a team of horses when we needed it. It was shorter than a regular canal boat and had no cabins. I used it one time to take about forty ton of coal from the pump house to a steam dredge working at Hathaway Road, and I guess this was the last boatload of coal to move on the canal.

“I remember when I was a boy seeing two canal boats carrying coal unloading at American Steel and Wire, probably the last two to come north as the company later got coal by railroad.

“To keep the bottom of the canal clear, we used an underwater grass cutter invented by Klepinger. It might have been used on the southern end of the canal, but I never saw one up here until he put it together. It was about four feet wide and about sixteen feet long, square at both ends. An old Ford motor ran a paddlewheel to push the boat and operate the grass cutting knives. It was like an old type mowing machine. There was a blade about three feet long for the grass growing on the canal bed and another to do the canal banks and it worked real well.

“For awhile the Chief Engineer who was Klepinger’s boss wanted to cut down the overflow at the dam at the pump house. We set up some gauges along the canal and every morning and at ten o’clock at night I had to take readings to see if we needed more water or if there was too much. If there was too much, I had to go to Mill Creek Aqueduct to open the overflow gate and let some water out. This got to be a chore, so I cut a plank on the side of the aqueduct, put a rope on it to raise and tie it up, and let a small amount of water out that way.

I had the water cut down until very little went over the dam and the level between Eleven Mile Lock (Lock 39) and Eight Mile Lock (Lock 40) was way down. This was fine for awhile, but then every morning the plank would be let down and water would rise in the canal. I couldn’t figure out what was going on.

“One morning I went past Mill Creek after some tools and saw two fellas looking at the aqueduct, so I stopped and asked what was the matter. They were from the Cleveland garbage plant that used to be just north of Mill Creek, which used water from the canal for the disposal operation. They said every time I lowered the water, their intake was above water level. After I told the Chief Engineer about this, he decided to forget about cutting down on the overflow, and the garbage plant had no more trouble.

“One piece of equipment used on the canal when my Step Dad was Captain of the State Boat was a hand dredge and it was used for sand and shale bars. There were two pontoons about 40 feet long attached to a framework about seven and a half feet wide. It just fit the width of the canal in most places. A short derrick-like affair was at one end and a winch was mounted on a platform at the other end with hand-cranks at waist level. An iron clamshell bucket, with a long wooden handle along its top that held a wheelbarrow or two full, was attached to the winch cable.

“The contraption was towed to the section to be dredged and tied to trees on both sides of the canal. One man took the handle of the clamshell, and walking along one of the pontoons hauled it to the far end where it was allowed to sink to the bottom of the canal. Two men then got on the hand cranks and winched the clam shell along the bottom of the canal picking up sand and shale, like a drag line. When the bucket neared the unloading platform, the action of the winch raised it out of the water to the platform where it was dumped. Two men then shoveled the load onto the berm bank. After three or four passes, the “dredge” was moved to another location and the whole operation was repeated. Hand dredging was a very tedious operation.

“A steam dredge worked up and down the canal every few years. It was owned by the State and operated by John Broughton of Peninsula. The last wooden dredge was built by the State at the Dog Pond near the Weigh Lock at Dille road, north of the Clark Avenue bridge, by Jacob McMillian whose grandson lives in Valley View. About 1922 when I was foreman, I helped launch a steel dredge at the pump house. It was built by American Steel and Wire and was supported on two pontoons.

“There were always sand or shale bars between Wilson’s Mill and Seventeen Mile lock (Lock 36), and then a long bar below that lock where sand and shale came in from the river, but we never used the hand dredge there. The bars formed by run-off from ravines draining into the canal.

“Another way to get rid of a small sand bar if a boat got stuck near the lower end of a lock was by “swelling, as we called it. With the lower gates opened and the lock level at the lower water level, we would open the wickets in the upper gates. This would create a small swell of about five or six inches. It didn’t work very well, but it could move a boat off a bar sometimes with a good pull from the team at the same time.

“I’ve seen ice-breakers on the canal. They were crude arrangements, nothing more than a heavy stone boat or sled built of four by four or four by six timbers with a pointed prow. It was loaded with stone. No one rode on it, and it was hitched to a team and driven forward against the ice to break a passage. It was only used to bring an ice-blocked boat into the nearest town to spend the winter. It was never used to clear the canal for traffic, though there wasn’t much of it between 1905 when I went to live on the canal and 1913 when the spring flood did so much damage.

“The State Boats were supposed to keep the towpath in shape. Muskrats always dug holes in the canal banks. They tunneled up to the towpath and we filled in the holes. If they dug a hole when the water was low in the canal, then there was a weak place in the bank when the water got higher and covered the hole.

“When the State of Ohio rebuilt the canal locks, my Step Dad, Charles Stebbins was Captain of the last State Boat on this part of the canal. There were contractors for the work, but the State maintenance crews also worked on the locks. Our crew did Deep Lock (No. 28) when I lived on the boat. Al Likens of Macedonia was the contractor for it.2 The canal wasn’t drained for any of that work.

“The only time it was drained was when an aqueduct had to be re-planked. I helped re-plank Tinkers Creek Aqueduct several times. The planking is tongue and groove two inch pine, treated with creosote and is good for about six or seven years. The aqueduct over Mill Creek is all steel, but the one at Tinker’s Creek still has a wooden trough.

“Going through an aqueduct wasn’t nearly as tricky as entering a lock. It is wider and you just went right through, and you considered yourself pretty good if you could get through without your boat touching the sides.

“Tow lines were half an inch thick and 98 feet long and nobody liked a new line, because it floated and wouldn’t sink to the bottom for passing other boats. When the tow line was water soaked it sank to the canal bottom real well.

“The flood in 1913 destroyed a lot of the canal south of the feeder dam to Akron, but the locks and both aqueducts north of it were all right. There were about six breaks in the towpath, three between Wilson’s Mill and the dam. There was one at Hathaway Road, another just north of Fourteen Mile Lock (Lock 37) and one south of Eight Mille Lock (Lock 40). They were all repaired in a couple of weeks by the maintenance boat crew with the help of crews from American Steel and Wire.

“When I was a boy there were still some parts of the floating towpath on Summit Lake. Whenever the State Boat went south, a launch from the Crescent Line of pleasure boats towed it from Lock 1 in Akron along the canal and across Summit Lake. The towpath from Exchange Street was in bad shape and teams couldn’t use it.

“There was no freight traffic on the canal when I worked on the State Boat for my Step Dad, but there were two excursion boats around Cleveland that took church groups and such out for picnics. One was owned by Bill Kelly and he kept it at the Weigh Lock. The other was owned by John Zimmerman who had a picnic ground between the canal and the river at old Rockside Road where the Slip Inn (also called Slip House) was located. Scholl’s Gardens and pavilion and dance floor was near there at Eleven Mile Lock. Scholl built part of what was the Old Boat House there before it burned down.

“Both were old freight boats. They used teams to pull them, but there was no stable on board. There was a roof for protection from the sun and rain and a narrow catwalk from bow to stern.

“Another boat I remember seeing was the William’s boat. The family lived in it and it was on the edge of the half-filled canal bed nearly out of the water, a hundred yards or so below where the State Boat was docked at Stone Road. Around the time the State rebuilt the locks, the Williams’ boat was used to take some lumber to Cleveland. It had dried out so much from being out of the water, I heard it almost sank on its trip north. We saw it some time later on the shore next to Lock 1 when we made a trip to Canal Fulton.

“I don’t know what happened to the state Boat I lived on. It was gone in 1921 when I came back to work on the canal. The only other State Boat I remember was at Canal Fulton.”

1When Dillow told me these tales in the late 70’s, the company was known as the Cuyahoga Works of United States Steel Corporation.

2The official records list P.T. McCourt as having the contract for Deep lock. That firm had the contract for a number of the earlier rebuilds south of Cleveland. This rebuild reportedly had poor quality concrete and a new contractor, plus “State forces” were required to ‘get it right’.