- Escape To Freedom Through Canal Towns

- History Of The Wabash And Erie Canal

- Canal Notes – The Aqueducts

- Canal Structures in Terre Haute

- Lightening Canal Boats

- Building A Legacy

- Whitewater Canal State Historic Site Offers Tours/Programs

- Lock Signs On Feeder Dam Trail

- W & E Marker Placed In New Haven

- St. Joe Feeder Clue In Old Article

- Creating A Data Base Of Boat Clearance Records

- Canal Clippings From Old Newspapers

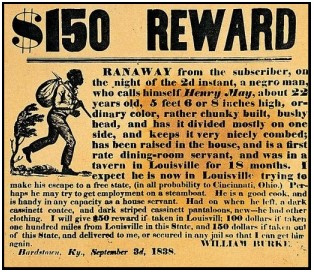

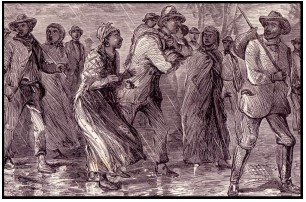

Escape To Freedom Through Canal Towns

By Carolyn I. Schmidt

It is estimated that Harriet Tubman, the “Moses of her People,” helped 300 slaves to freedom in the 1850s. She chose to use the safe route avoiding the Niagara Falls area and going inland to St. Catharines. She used Underground Railroad established routes and went from Dorchester county to Baltimore or Camden, Maryland and from either of these places to New Castle, Delaware then on to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. From Philadelphia she could go directly to Rochester, New York or go to New York City, then to Athens, Syracuse and finally Rochester, New York. From Rochester she went to Buffalo, New York and on to St. Catharines, Canada. Harriet traveled under the cover of night following the North Star along the Eastern Shore. If the star was not visible she used tree moss and observed currents in rivers and streams to guide her north.

Stewart’s Canal had played an important part in her life, now other canals helped her. When she rescued Tilly, she traveled through the Delaware Canal down the Chesapeake to Baltimore. At other times she followed the canal systems of New York State and southern Ontario. She went to Troy, New York, traveled west on the Erie canal, passed the bottom of the Finger Lakes and, when needed, followed the Welland Canal from Port Colbourne to St. Catharines.

During canal days in Indiana, citizen’s of towns along the canal helped fugitive slaves escape. Sometimes they followed the canal towpath under the cover of darkness since it was level and easy to follow. Other times they were taken by wagons from one “station” to another. Luckily some escape stories have survived that were recorded by early Indiana historians.

Edward Peabody was interviewed by F. S. Bash for his column in the Huntington Herald about fugitive slaves who followed a route through the vicinity of Lagro, Indiana, which was located on the Wabash and Erie Canal. Peabody said, “It’s all true. I have seen as high as half a dozen leave our barn at once. My father never turned any of them away. But it was necessary to be quiet about it on account of the fugitive slave law. It was required under the law, that officers arrest colored people and hold them until the owners came to claim them. But, smiling, somehow they would always get away. I remember one time especially when there was a deep snow that a runaway darkey was held here in Lagro at Gillespie’s, who lived where the school building now stands. The negro’s shoes were taken from him so he would not try to escape with his bare feet in the snow. Bill Collins was supposed to be guarding the darkey, but the black man made his escape just the same, shoes or no shoes, running right through the snow in his bare feet.

“About the last black man from the slave states that sheltered and hid in our barn was a strapping big fellow and I hauled him myself to a certain point in the vicinity of North Manchester where he would be looked after by a Quaker preacher. He told me all about how he came to escape. He said he had just been sold to an old planter, who was said to be hard and cruel to his slaves, and owned a plantation in the far south. It seems this darkey was much liked by the white people of the neighborhood, who hated to see him taken so far away amongst strangers. A bunch of white children pitied him and told him he ought to try to skip out for Canada. They even helped him get away, so he stated. I couldn’t help but feel anxious for his success in reaching Canada and wished many times I had written down my address and given it to him with a request to get someone to write me a letter in case he gained the land of freedom. I think that was in 1859 and I do not remember of any more staying in our barn after that time.”

At another time Bash interviewed Henry Bradford, who had lived along historical road Highway No. 9 between Huntington and Marion, Indiana. During his interview Bradford showed Bash a picture of his father and said, “Right there was an abolitionist if there ever was one. He was a ‘conductor’ on the underground railway that followed this highway through Mt. Etna before the war. Nate Cogshell and Mose Bradford, the latter my uncle, helped him and so did I after I was old enough. My beat was from Joe Bradford’s in Grant county, to Art McFarland’s not far from Monument City. This route was known as the eastern line. Another was further west through Lagro. The slaves in coming north would make for a neighborhood of Quakers near Fairmount and from there they were delivered to us folks.

“Sometimes when the owners of runaway colored people were in hot pursuit, accompanied by a

United States marshal, we had to be mighty careful to avoid arrest ourselves. One close shave I

remember well was when a mulatto woman came through. Her master and an officer were close on her track here in the neighborhood of Mt. Etna. They even passed right by her in McFarland’s closed spring-wagon. The colored girl peeped out from her concealment and saw that one of the men was her master. He and the officer were back-tracking at the time, but just passed on without investigation, or the jig would have been up.

“The mulatto girl really showed no trace of her race, for she was as white as a good many of our native women and was decidedly handsome. The girl told Art McFarland that she was valued highly on account of her good looks and because she knew how to take care of guests in society functions given by wealthy people. She stated that the last time she was sold on the block the price brought for her was around five thousand dollars. We had to detain her here several days so those on her track would lose all trace of her.”

Jake Nuck of Huntington was also interviewed by Bash and said that his father, Matthais Nuck,

had told him the following story, which reveals the treatment some slaves endured:

“My father said he always heard that a colored man had a hard skull. He used to laugh as he told about seeing a canal man and a Negro quarrel on the tow-path near the Forks [of the Wabash]. The white man picked up a board and slammed it over the head of the colored man so it cracked like a gun, but the darkey didn’t even stagger. He leisurely walked away whistling as if nothing had happened. My father said if it had been his head he would have dropped dead.”

William Cochrum wrote books in which he told how negroes making their way north were hidden in Gibson county, Indiana. His family was heavily involved in the Underground Railroad during the 1850s. In The History of the Underground Railroad he writes: “We had a barn built of peeled hickory logs, forty feet square and it was floored with thick planks so we could use horses in tramping wheat on it. Under the floor we had a cellar that we used for storing potatoes, turnips and apples. It was in this cellar of the barn where the escaping slaves were kept before being passed on to the next station farther North.” Many slaves traveling north made a stop in the Cockrum barn.

In Pioneer History of Indiana Cochrum reports another incident where the negroes were hiding in a thicket and were taken from their hiding place under a small load of straw to the barn of Isaac Street before a raiding party could capture them. Then under darkness, Street, with the help of Thomas Hart, took them north of White river and delivered them to a friend [Quaker].

William also related the time when Andrew Atkins was stopped on the way to James W. Cochrum’s home and shown a hand bill. It gave the description of seven runaway slaves and offered one thousand dollars for their capture. Andrew feared the slaves would be captured by men guarding the bridge. Later that day he learned of a plan to trick the guards by Jerry Sullivan, a full fledged abolitionist who worked for James Cochrum. Jerry convinced William Cochrum and two young boys who worked on the farm to go fishing and stay late into the night. Andrew Atkins was to send his brother and a neighbor boy to go with them.

Andrew thought the boys would only turn the guards’ horses loose and drive them away. But

Jerry Sullivan had other ideas. He took old newspapers and rubbed wet powder all over them

leaving lumps that would flash when burned. He dried the paper in the sun, took a long fuse he

had been using to blast stumps, took lots of flax strings and made six large brooches out of the

newspapers.

Basil Simpson, who lived on the bluff a little west of the bridge [over the Patoka river], watched and told Jerry the guards had put their seven horses in a patch of small saplings less than one hundred yards southwest of the Dongola coal mine shaft. The boys found the horses, stripped the saddles off them, and piled the saddles at the base of a large tree. They led the horses to the road where Jerry tied a brooch inside of six of the horses’ tails with about six inches of fuse sticking out. He made a larger brooch for the seventh horse out of a loosely tied saddles blanket filled with powder and a long fuse. He lighted the fuse, turned the horses loose, and the boys followed on their horses yelling like Indians. “The brooches commenced to pop and fizz at a great rate and the horses were going like the wind. In a little while the big bomb went off and I doubt if anyone ever saw such a runaway scrape where there was an equal number of horses.” The boys loaded their guns fired sometime, but there was no one there. The guards had been scared off.

The boys found two pair of boots which of the guards had used as pillows under a bed they had made. They cut the boots into strips and threw them plus a lot of rock rolled up in their bed into the river. The boys went back after the guards’ saddles, cut them up, and threw them into the river as well.

The slaves at the time were safely hidden in thick brush and tall grass by a big pond about ten miles east of Oakland City. That night they were taken over the Patoka river at Martin’s ford and piloted along Sugar creek until they came to a wagon waiting for them that took them to Dr. Posey’s coal bank where they were hidden once again. After remaining there the next day they were ferried across White river in skiffs and turned over to another friend. They were rushed to Canada and freedom.

Portions of Indiana’s canals and towns along them were instrumental in helping slaves escape

to freedom, which was good. However, a sadder use of the Wabash & Erie Canal in Indiana

was that it was used to transport Native Americans from their homes to the west—but that is

another story.

Click here to return to the Table of Contents

History Of The Wabash And Erie Canal

One hundred sixty-three years ago the Evansville Daily Journal on September 5, 1859 ran the

following extract that had previously been published in the American Railway Review, a weekly

paper devoted to information regarding railroads and works of internal improvements. The

extract was published in advance of its publication as a part of Col. Stuart’s American

Engineering.

WORKS OF INTERNAL IMPROVEMENT IN INDIANA WABASH AND ERIE CANAL.

The drainage of the State of Indiana, in its general aspect, is from the north-east to the south-

west. The leading feature, giving character and direction to the whole system of water courses, is the Wabash river.—Taking its rise in the north-east, in the vicinity of the boundary line between the States of Ohio and Indiana, this chief river of the State finds its junction with the Ohio in the extreme south-west, traversing in its course a distance of over 500 miles. With its largest tributary, the White river, intersecting by its two tributaries the central and southern portions of the State, the Wabash drains three-fourths of the territory of Indiana. The near approach of some of its tributaries in their extreme sources to the Ohio river, forms a remarkable feature in the topography of the State. At one point (Madison,) water falling within three miles of the Ohio, runs in the opposite direction, finding its way to the distant Wabash.— Indeed, the Bluffs of the Ohio above the Falls, within a few miles of the river, reach the altitude, corresponding generally with the higher table land between this river and Lake Erie, which is found along the east line of the State, near the sources of the White river and the White-water.

The influence of a pervading and controlling drainage like that of the Wabash Valley, is giving shape and direction to works of internal improvements, especially so long as water communication was the end in view, will be apparent to the professional mind.

One of the upper tributaries of the Wabash (Little River,) takes its rise in an extensive marsh or

depression, distant at its summit, but four miles from the Maumee river, at the junction of the St.

Mary’s and little St. Joseph’s, once the site of Fort Wayne, now transformed by the magic touch of

American civilization and enterprise, from the frontier military post, to the beautiful young city bearing the same name. The water shed or high table-land, dividing the waters of Lake Eire from

the draining into the Ohio river, which on the route of the Ohio Canal, near Akron, is elevated over

400 feet, and of the Miami Canal, 385 feet above the Lake, is here depressed to 190 feet, rising

again to 350 feet above the Lake level, at a distance of 25 miles to the north-west. The marsh,

or valley, in which Little river has its source, drains also to the Maumee, the low water of which stream is here only 24 feet below this summit.

The idea of an artificial water communication connecting the Wabash and Maumee rivers, through the remarkable depression in the dividing highlands, was, no doubt, at an early period, with more or less distinctness, in the mind of some of the intelligent gentlemen stationed at this government’s out-post. The early French traders, representing an inferior civilization, had actually used this route as a channel of commerce for on or two centuries before, in their patient journeyings between Detroit and Vincennes, using their primitive water-craft, the Pirogue, with a portage of only seven miles. The place of embarkation on the Wabash side of the summit, even down to the period of commencing the canal, bore marks unmistakable, of long usage as a camping-ground in the destruction of all timber over a large area. A gentleman ( G. W. Ewing, Esq.) who has since acquired distinction and wealth in the pioneer walks of commercial enterprise, stretching his operations from Fort Wayne to the sources of the Mississippi and Missouri, recently informed the writer that in his youth, as late as in 1822, he superintended his father’s teams in drawing upon wagons, across this portage, both the pirogues and their valuable cargoes of furs, under contract with the French traders. The eastern end of the portage—the head of the Maumee—for long ages in the past had been a place of rendezvous for the Indians, for which, in their canoes, the junction of the rivers afforded facilities. The Indian name was Kekiogue, as pronounced by the Miamis, or Kekiounge, in the Pottawatomie dialect. For miles in extent along the banks of these beautiful rivers, the original heavy forest had long before given place to the Indian villages and cornfields.

It was in the retreat from the perilous attack upon one of these Indian towns, on the east bank of the St. Joseph, near its mouth, in October, 1799, that the army of General Harmar, in re-crossing the Maumee river, was subjected to a slaughter so terrific, as to give rise to the tradition that the river for a time ran blood For ages this has been a battle ground, not merely between the Indians and the whites, but, anterior to this, between the different tribes of Indians, as their feuds have arisen out of the contests for hunting grounds, or from the murder of their braves. The place of burning prisoners was pointed out near the junction of the rivers, by Chief Richardville, during his life.

It is probable that attempts at ascertaining the height of this summit above the Maumee, with such leveling instruments as could be had, may have been made at an early period by surveyors of the public lands or others. This fact, however, was indicated with sufficient accuracy by the high water mark of the St. Mary’s. During extreme high water, about the year 1824, Gen. Tipton, the Indian Agent at Fort Wayne, and George W. Ewing, pushed a canoe nearly across to the water of the Wabash.

In the treaty of 1826, between the Miami tribe of Indians and the Government of the United States, through it commissioners, Lewis Cass, John Tipton, afterwards United States Senator, and James B. Ray, then Governor of the State, by which the Indian title, in all this section of the State, with the exception of certain reserves, was extinguished, the idea of the Canal found its first official and authoritative recognition.—The treaty contained the following clause, referring to the extensive districts reserved by the Indians along the line of the proposed Wabash and Erie Canal:

“And it is agreed, that the State of Indiana may layout a canal or road through any of these

reservations, and for the use of a canal, six chains along the same are hereby appropriated.”

The next step in the progress of events was the procurement, through the agency of the members of Congress from Indiana, of a survey of the Canal by a corps of United States Topographical Engineers. The liberal theory of John Quincy Adams’ Administration on the question of internal improvements, whether sound or unsound as a general policy, favored this application. A corps of engineers under the command of Col. James Shriver, was detailed for the survey by order of the War Department. After a tedious journey through the wilderness, the survey was commenced at Fort Wayne in May or June, 1826. But little progress had been made, when the whole party were prostrated by sickness, and Col. Shriver died soon after in the Old Fort. He was succeeded in command by Col. Asa Moore, his assistant, under whose direction the survey was continued during 1826 and 1827, down the Wabash to the mouth of Tippecanoe, then considered the head of navigation.—The survey was continued along the Maumee in 1827 and 1828, until Col. Moore also fell a victim to disease, so prevalent at that time in these forest-covered vallies [valleys], dying in his tent at the head of the Maumee rapids, on th 4th of October, 1828. This survey was completed to the Maumee Bay by Col. Howard Stansbury, who, from the beginning had been of the party, and who, at a later period, gained distinction by his pioneer expedition to Salt Lake, under the orders of the War Department.

Following this survey, was the grant of land in aid to the construction of the work, obtained mainly through the efforts of the delegation from Indiana.* By this act, approved March 2d, 1827, Congress granted to the State of Indiana, one-half of five miles in width of the public lands on each side of the proposed canal, from Lake Eire to the navigable waters of the Wabash, amounting to 3,200 acres to the mile. The terminus of the Canal, and therefore of the grant, was at that time established at the mouth of Tippecanoe river, a distance from the lake of 213 miles. At the session of the Legislature of 1827 and 1828, the grant was accepted by the State, and a board of canal commissioners appointed, consisting of three members, to-wit: Samuel Hanna, David Burr, and Robert John.

The commissioners were directed to re-survey the summit division in 1828, and for this purpose

employed as engineer Mr. [John] Smythe. Sickness again interrupted the progress of this work. Mr. Smythe accomplished no more, after arriving at Fort Wayne, than to gauge the river and adjust his instruments, where he was laid aside for the season. In this emergency, the commissioners themselves, though not engineers, took hold of the instruments, and with the aid of a competent surveyor, completed the survey of this division of thirty-two miles.

The munificent grant of the public domain before alluded to, was the first of any magnitude made for the promotion of public works, and may, therefore, be viewed as initiatory to the policy afterwards so extensively adopted, or granting alternate sections for those objects; and in the benefits of which, many States have so largely shared.

The grant having been made by the terms of the Act of Congress, wholly to the State of Indiana, while eighty-four miles of the route were within the limits of Ohio, the question of State sovereignty seemed likely to arise in a practical shape. Ohio, it was conceded, would refuse permission to another State to cut her soil, or exercise jurisdiction in any shape within her borders. Commissioners, with plenipotentiary powers were, therefore appointed by both states, to wit: W. Silliman, of Zanesville, on the part of Ohio, and Jeremiah Sullivan of Madison, on the part of Indiana, by whom a compact was agreed upon in October, 1829, which after more delay on the part of Ohio, was ratified by both States—Indiana agreeing to surrender to Ohio the land within her territory, and Ohio stipulating to construct the canal, and guaranteeing its use to the citizens of Indiana on the same terms as to her own citizens. From this period, the canal, though one work as respects its commercial interests and bearings, became separated into two divisions, as regards its finance, construction and management. It is to the Indiana division that the following historical descriptions chiefly refers.

The portion of this land-grant, falling in Indiana, east of Tippecanoe river, amounted to 349,261

acres as the selections were finally made and approved.

During the year 1830, the middle or summit division of thirty-two miles, was located and prepared for contract by Joseph Ridgeway, Jr., of Ohio, an engineer of experience and skill, employed for this purpose by the canal commissioners. The actual construction of the work was not authorized until the session of 1831-1832, when a law was passed empowering the board of commissioners to place the middle division under contract, and creating board of fund commissioners, and authorizing a loss of $200,000 on the credit of the State. Jeremiah Sullivan, Nicholas McCarty, and William C. Linton joined the first board of fund commissioners, whose organization took place at Indianapolis on the 28th February, 1832. The board reported the entire Canal Fund at that date to be $28,651, received from the sale of canal lands. Jesse L. Williams was appointed chief engineer of the canal in the spring of 1832.

It was in 1832 that the State of Indiana, through her fund commissioners first promoted her securities in financial circles abroad. The caution of the primitive period, and their dread of foreign indebtedness prevailing in the councils of the State, are exemplified in the smallness of the loss to which the fund commissioners were limited. For the payment of the loss, the lands granted by the General Government were pledged in addition to the faith of the State—a pledge which the State, to her credit, has sacredly maintained, and provided for in the subsequent adjustment of her State Debt. The first loan made by the State was an exchanged for one hundred thousand dollars of six per cent bonds, which were taken by the House of J. D. Beers & Co., of New York, at a premium of 13-1⁄4 per cent.

*In these efforts at Washington City, Hon. John Test, of the House of Representatives and John

James Noble, of the Senate, were prominent and efficient.

Click here to return to the Table of Contents

Canal Notes – The Aqueducts

By Tom Castaldi

How did a Wabash & Erie Canal boat, traveling west pass over one of hundreds of streams flowing across its watery path? The whole idea of a canal is to have stretches of still, flat water for moving tons of cargo powered by tow horses or mules.

As a rule, quiet canal water will not cut neatly across a babbling brook. Laws of nature being

what they are, water seeks its own level, and canal water would be lost going with the flow of a

wild stream. To control canal water, contractors built culverts or arches to flow boats over streams. For larger rivers, aqueducts were built.

An aqueduct was like a long, wooden wagon bed that, swelled watertight when the wood became damp making a bridge of water over water for Wabash & Erie vessels.

Probably the most celebrated aqueduct was the one over the Saint Mary’s River at Fort Wayne.

Artists’ paintings depict a 160-foot covered structure that protected the bridge from the elements. At each end, the 17-feet wide bed of the aqueduct matched up evenly with the canal channel. Today you can see the stone abutment on the west bank of the Saint Mary’s north of the Main Street Bridge. The River Greenway Trail passes inches away from the old aqueduct structure.

Wayne, Indiana by Ralph Dille

A longer uncovered aqueduct crossed the Eel River at Logansport. It was 200-feet long and what remains of its abutments and five piers can be seen today on the river north of High Street where it meets 5th Street. At Aboite River near U.S. 24, west of Fort Wayne, the stone abutments and several timbers of Aqueduct No. 2 are still visible.

Had it not been for aqueducts, arches and culverts, the entire idea of canals would be like pouring water…down a wet hole.

Click here to return to the Table of Contents

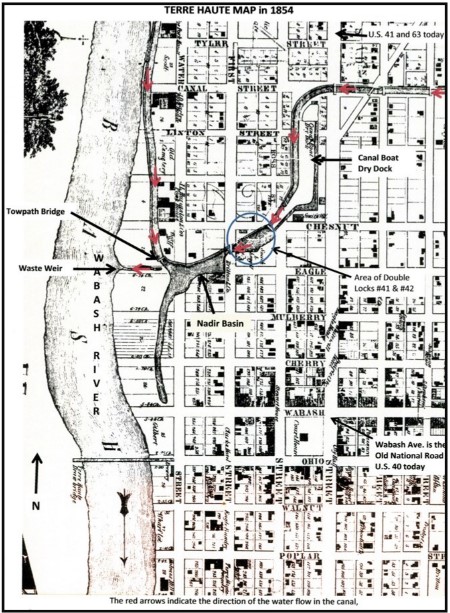

Canal Structures in Terre Haute

Article and pictures by Sam Ligget

by the Terre Haute Street Department.

Terre Haute was laid out in 1816, the same year Indiana became a state. The land office in Vincennes records Joseph Kitchell as the original purchaser; but within a few days, he sold out to the Terre Haute Land Company. The community was situated on a prairie running parallel to the Wabash River just below the site of Fort Harrison. Terre Haute lies on the east bank of the Wabash River on a bluff. It would become the intersection of the National Road and the Old State Road. The Old State Road connected Lafayette (Fort Ouiatenon) and Vincennes (Fort Knox), Indiana. The transportation system of Terre Haute would come to include many roads, many railroads, river traffic, airports, the interurban, and the Wabash and Erie Canal.

The definition of the word nadir according to the American Heritage Dictionary is “the place or time of deepest depression, lowest point.” On a canal, a nadir is the lowest level between two high points. One such point on the Wabash and Erie Canal was between the Fort Wayne summit (768 feet elevation) and the Lockport (now Riley) summit (571 feet elevation). It was a 12 3⁄4 mile stretch of the canal from Terre Haute (499 feet elevation) in Vigo County north to Clinton Lock in Parke County. This section of the canal ran along the eastern edge of the Wabash River bottoms. A large basin was constructed at the southern end of this stretch to help manage the water coming from the north (Fort Wayne) and the east (Lockport). Off of the nadir level basin were four significant canal structures besides the basin—a waste weir, a towpath bridge, a double lock, and a dry dock.

Basins in Terre Haute

There were two basins in Terre Haute, but only one was on the nadir level. The nadir level basin was larger than the average basin, and it had a large backwater trailing to the south almost to the National Road. The basin stretched two blocks east and west and about a block and a half north and south.

The other basin in Terre Haute was on the east side located just to the east of the Hulman & Company building’s location today. A bridge on the National Road divided this turning basin into two equal parts.

Waste Weir

A waste weir was constructed on the nadir level basin to allow excess water coming into the nadir level from the higher levels to be released into the Wabash River. A waste weir is a gate that can be used to control the level of the water in the basin. The amount of water let out would depend on how many canal boats were locked through and the amount of rain in the area at any given time.

Towpath Bridge

There was a towpath bridge on the nadir basin. It was constructed so the mules or horses towing a canal boat could switch which side of the canal they were pulling from. Using the terrain, it was practical to have the towpath on the west side of the canal north of Terre Haute. Once the canal turned to the east off the basin, it was no longer necessary for the towpath to be on one side or the other. But since the dry dock was on the southeast side of the canal, it made sense to switch the towpath side to avoid that as well as several businesses.

Double Lock # 41/42

The only double lock on the Wabash and Erie Canal was lock # 41 and # 42 just off the nadir basin. The upper gate of lock # 41 was the lower gate of lock # 42. The two-lock combination raised the water level 19.2 feet above the nadir level. The location of lock # 41/42 was near the intersection of Chestnut and Second streets in Terre Haute. With each lock being 60 feet long, the length of the double lock would have been more than 120 feet. Both locks were of the Timber Crib plan. Looking at the terrain in this location today, one would be puzzled by the 19.2 feet change in elevation. A lot of fill was dumped onto more land than just the canal structures when the canal no longer operated.

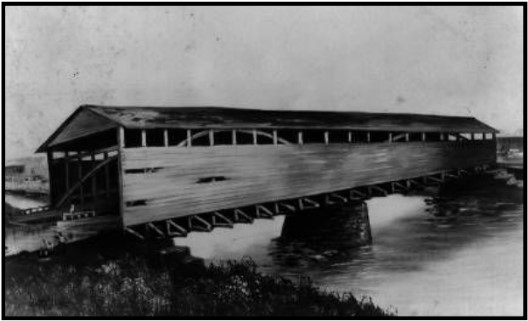

Dry Dock

Near the intersection of Second and Chestnut streets in Terre Haute was a dry dock. A dry dock is a chamber in which canal boats can be built, repaired, or modified. A dry dock is built and operates much like a lock. This dry dock could raise/lower the water level 10 feet. It measured 109 feet by 16 feet. The larger size of a dry dock over a lock was to allow men and equipment room to work on the boat. In a dry dock, the water is drained completely out allowing the canal boat to settle on a supporting structure. This dry dock was probably in this location to take advantage of the 19.2 feet water level change of the double lock # 41/42. Another advantage would have been the sandy soil at this site, which allowed the ground to dry out much quicker once all the water was out of the chamber. Workers could then stand on firm ground to work on the part of the canal boat that would normally have been below the water line.

This photo was taken at the Chittenango Landing Canal Boat

Museum within Old Erie Canal State Historic Park.

Looking at this part of Terre Haute today, a person would never guess that a canal was ever a part of the landscape. This land has been filled in the full 19.2 feet that the double lock raised the canal above the nadir level. The fill was extended to the edge of the river thus making the bluffs at this point even higher than they were when the canal was built.

At one time, this 24 square block area would have been a very lively canal center. Either directly or indirectly the canal would have meant employment for many people. Canal contractors, canal construction workers, canal boat captains, canal boat crew members, canal commissioners, and businesses all took advantage of the canal being here.

Note: CSI thanks Sam Ligget for all his work with the Terre Haute Street Department to get this sign placed and the street department for furnishing the poles for the sign and erecting it. Also note how close it is to the Vigo County courthouse.

Click here to return to the Table of Contents

Lightening Canal Boats

By Carolyn Schmidt

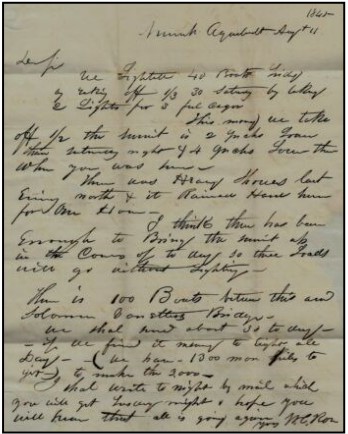

Neil Sowards, CSI member from Fort Wayne, found the following letter on E-bay. The seller incorrectly titled it as “Making Lights for Canal Boats” and misspelled Aqueduct as “Aquaduct.” Although it is very difficult to read its author’s spelling and handwriting, when it is read carefully you will find that it is about “lighting” canal boats. They were not putting lights on canal boats, they were removing whiskey from the boats to make them weigh less— “lighting” — since there had not been enough water at the summit. Since the letter is from Newark, Ohio, this letter was about the canal boats at the Licking summit of the Ohio and Erie Canal. Luckily it finally rained and Mr. Rose thought they would not need to lighten any boats that day.

To R. F. Lone Eng.

Honesdale P.A.

1845

Newark Aqueduct August 11

Dear Sir,

We lighted 40 boats Friday of wky [barrels of whiskey] off 1/3 30 Saturday by taking 2 lights for 3 full cargoes. [Took off enough for 3 more boat loads]

This morning we take off 1/2 the Summit is 2 inches lower than Saturday night & 4 inches lower then when you was here.

There was Heavy Showers last evening north & it Rained Hard here for one hour.

I think there has been enough to bring the [Licking] summit up in the course of the day so these loads will go without lighting. There is 100 Boats between this and Solomon Vanetters Bridge—We shall put about 30 today if we find it necessary to light all day. We have 1300 more [barrels of] whiskey to get to make 3,000.

I shall write to night by mail which you will get Tuesday night & hope you will hear that all is going

again.

Yours,

W. C. Rose

The water supply at a summit is more crucial in operating a canal than elsewhere. Water being fed into the canal at a summit goes downhill in two directions where as in other feeders it flows only in one direction. It takes twice as much water to feed a canal going in two directions.

We read many newspaper reports about canals not being navigable due to breaches or low water and the inability to float boats. This letter shows how they tried to decrease the weight of their cargoes in order to navigate in shallow water.

Click here to return to the Table of Contents

Building A Legacy

By Bob Schmidt

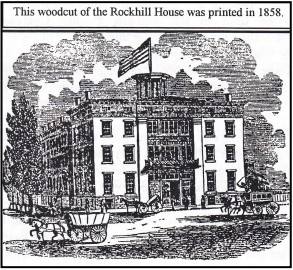

The Fort Wayne Journal Gazette ran articles under this title describing the demolition of St Joseph Hospital, the first hospital in this city. Several persons commented on their memories of this institution of healing. CSI Director, Tom Castaldi, had earlier written about the hospital’s history and his comments were again included in the newspaper.

St. Joseph Hospital was also a special place for canallers as it was here in Fort Wayne on the southwest corner of Broadway and Main Street that William Rockhill built a 4 story, 65 room hotel to accommodate canal and rail travelers. Rockhill began construction in 1836 on this site just south of his home at 1025 W. Berry. The hotel was located about 1 block north of the Wabash & Erie Canal. At that time this location was about 1⁄2 mile west of the city. Progress was slow and by 1840 only the walls and the roof were completed Dubbed “Rockhill’s Folly” the structure sat in various stages of construction for 13 years. Once it was partially completed, various meetings, fairs and exhibits were held there. By 1854 it was finally ready to accommodate overnight guests.

Philo Rumsey, who came to Fort Wayne in 1832, had married William Rockhill’s daughter, Rebecca, on March 7, 1838. Rumsey was a merchant and a tailor. In 1849, upon the death of Maria Vermilyea, Philo had moved his wife and two children west of town to the Vermilyea Inn along the Wabash & Erie Canal. Here he learned the ways of inn keeping. His father-in-law, William Rockhill, had great faith in him and made him the manager of the Rockhill House in 1854. He continued in that position until the hotel was sold in 1868.

The 1854 hotel opening was a grand celebration with a banquet for the community leaders and a tour of the most luxurious rooms and other accommodations. One of the features that was provided to those staying in the hotel was an omnibus service to the canal landing and the railroad stations.

and Main in Ft. Wayne, Indiana, was later

surrounded by additions to St Joseph Hospital.

William Rockhill died on January 15. 1865. He was buried in Fort Wayne’s Lindenwood Cemetery.

By 1867 the Rockhill House was for sale. Philo Rumsey moved to Omaha, Nebraska where he managed the Crozzen House. Finally he moved to manage the Palace Hotel in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Both he and Rebecca died in Omaha, but their final resting place is in Lindenwood Cemetery.

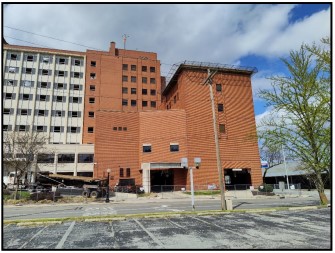

In 1868 the St Joseph Benefit Association purchased the hotel. Bishop Luers was able to persuade Mother Katherine Kasper to come to Fort Wayne along with 8 sisters from the Handmaids of Jesus Christ and operate the first hospital in Fort Wayne. They arrived in May 1869. They initially moved into the old Rockhill hotel and called it St. Joseph Hospital. It soon became too small. The hospital was expanded in 1879, 1912 & 1929, etc. and encompassed the original hotel.

Fort Wayne’s first surgery was performed here in August 1869, by Dr Isaac Rosenthal. He went on to be the first Chief of Staff for medical services at St Joseph.

Years later it was taken over by the Lutheran Hospital Group and specialized in burn victims.

Recently a brand new Lutheran Hospital Downtown Unit was built immediately west of the old hospital. In late April 2022 destruction of the old St Joseph Hospital began and what remained of the old Rockhill House was lost forever.

For more information on William Rockhill and Philo Rumsey:

Biographies on the CSI website: indcanal.org.

Find A Grave: Newspaper Biographies

William Rockhill FG # 7116987

Philo Rumsey FG # 81592124

Rebeca Rockhill Rumsey FG # 87372101

Click here to return to the Table of Contents

Whitewater Canal State Historic Site Offers Tours/Programs

Even though the “Ben Franklin III” broke apart after her removal from the Whitewater Canal and the site won’t offer boat rides this year, they are open and are offering special tours and programs. In a quarterly report from Jay Dishman, Site Manager, he writes:

LOOKING FORWARD

The site opened for the season on April 1 and new this year, we are offering programs at the site. This is a great way for visitors to have new and exciting experiences while also attracting return visitors and members.

Upcoming programs include:

| Whitewater Canal Guided Tours | May 7 & 28, Jun 11 & 25 and July 2 & 16 |

| Canal Field Day | May 28 |

| Build a Boat | June 11 |

| Juneteenth Free Admission Day | June 18 |

| Making the World Move Simple Machines | July 16 |

Find all program details, prices and registration information, as well as the mill demonstration schedule, on the Whitewater Canal State Historic Site webpage.

SITE IMPROVEMENTS

In 2021, a new floor was installed in the gazebo which also got a fresh coat of paint. The bridges across the canal through town were also painted and the roof of the aqueduct bridge was fixed and painted.

In spring 2022, the Ben Franklin III was removed from the canal and drydocked for inspection. Next steps are currently being determined for the boat as well as preservation of the historic elements of the site including the aqueduct and locks.

Even though we do not currently have a boat operating at the site, our canal guided tours and new

programming provide interpretation on the history of the canal and the importance of canal boats.

VISITATION

School field trip visitation numbers were hit the hardest by COVID. Despite that the site has been able to interact with both local and statewide schools. Program Developer Aaron Martin designed and implemented 30-minute virtual classes which were offered for free. We look forward to offering these virtual classes again during the off-season (November through March).

Click here to return to the Table of Contents

Lock Signs On Feeder Dam Trail

As part of the Canal Society of Indiana’s signage program to mark canal sites, we received a request for three signs to mark the locks along the Whitewater Canal Feeder Dam Trail between Metamora and Laurel, Indiana from Shirley Lamb. Three 2 ft. x 4 ft. signs were made and delivered to Shirley earlier this year. She recently posted pictures of these signs on FaceBook with the following note: “Thank you Indiana Canal Society for the new lock signs…they look great? You can access the locks on the Laurel Feeder Dam in Metamora.” and included the following pictures. They show Lock No. 26 Ferris, Lock No. 27 Murry and Lock No. 28 Simonton.

Click here to return to the Table of Contents

W & E Marker Placed In New Haven

When placing a canal marker CSI tries to ask some local person in the area to make contact with the property owner. We wished to mark the path of the Wabash & Erie Canal between the east side of New Haven and the Gronauer Lock at I-465. Randy Harter, a local historian, made the contact with the property owner, received his permission to place the sign and then contacted Dave Jones of the New Haven street department. They placed the sign on an existing pole. This is not ideal. We fear it will be taken down by the power company. Further contact with the street department will be made. We thank Randy for all his work in obtaining permission and getting the sign to the street department.

Click here to return to the Table of Contents

St. Joe Feeder Clue In Old Article

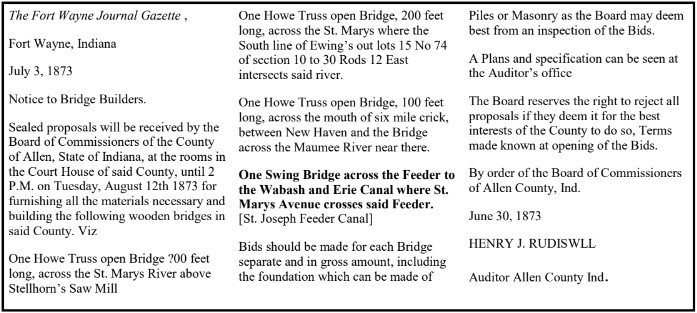

One of the Canal Society of Indiana’s goals is to reconstruct the history of Indiana’s canals. Recently Craig Berndt, CSI member from Fort Wayne, Indiana, found a clue relating to the St. Joseph feeder in a local newspaper. It helps us to understand how the feeder was still used after the mainline Wabash & Erie Canal was officially closed.

History tells us that ground was broken for the Wabash & Erie Canal and the St. Joseph feeder project in 1832 at the site where the feeder would join the mainline canal at Rumsey and Wheeler Streets in Fort Wayne. Then the feeder was begun by building a large dam on the St. Joseph River 6 miles and 34 chains above the main canal. The dam was one of the most important structures along the canal. It was 17 feet high and spanned 230 feet across the river. It was made by felling trees, placing them in the bottom of the river with their branches pointing upstream, building a row of log cabin type structures filled with sand, boulders, and gravel on top of them, and then covering the entire structure with planking and building an apron below the dam so water would not undercut it. This summit was 198 feet above the level of Lake Eire (790 feet above sea level). The anchorages for the dam were 110 feet long, 20 feet wide, and 25 feet tall.

The St. Joseph Feeder started at a guard lock just above the feeder dam at the bend in the St. Joseph River across from present day Riverbend Golf Course. Its channel followed south to Culvert No. 1 over Beckett’s Run. It continued to follow the west bank of the river across St. Joe Center Road to Johnny Appleseed Park. It then turned southwest following Spy Run Extension. It crossed Spy Run Avenue near today’s Burger King at Clinton Avenue and continued southwest through the Y.M.C.A. property on Wells Street to where it intersected the Wabash & Erie mainline at Rumsey and Wheeler streets in Fort Wayne.

The feeder supplied the mainline Wabash & Erie Canal with water as far west as the Forks of the Wabash below Huntington and as far east as Defiance, OH. The latter was accomplished by diverting water from the mainline into Six Mile Reservoir near Antwerp in the Spring, when the feeder had an abundant water supply and releasing it in the summer to supplement the mainline to Defiance. This stabilized the water level in the Ohio section of the canal.

Other important structures on the feeder were:

- A timber guard lock, which was built where the feeder canal joined the reservoir created by the dam. It prevented the canal from being washed out in time of flood and controlled the flow of water into the feeder canal.

- An aqueduct across Spy Run Creek. It had a wooden trunk with a 28 foot span that rested on stone abutments on either side of the creek.

- Culverts 1-4 that let the waters of creeks pass under the feeder’s prism.

- Road bridges 1-3 that allowed roads to pass over the feeder’s prism.

The feeder project took two years. It was completed in 1834 at a cost of less than $16,000.

Although the feeder was built to supply all the water the mainline Wabash & Erie and adjacent mills would need, they apparently underestimated this need. By 1845-1846 local newspapers were reporting shortages of water, talked about suspending water power to businesses, and proposed building other reservoirs. These reservoirs were never built.

Around 1866 a report to the Indiana Legislature on the condition of Wabash & Erie Canal said that the Summit Division, “in respect to supply of water, is the key to the whole line.” It would be necessary to raise the St. Joseph Feeder Dam to its original height. It had settled about ten inches over the past ten years. Raising the dam by successive layers of plank would make it perfectly water tight, which was essential on the summit. The guard lock at the head of the feeder was very decayed and needed to be rebuilt and secured against damage as soon as possible.

The report also said that the feeder had become so obstructed by the washings and accumulations of sediment over the past thirty-four years that it needed to be thoroughly cleaned out with a dredge in order to pass the necessary supply of water. This should not be delayed.

The Indiana Legislature abandoned the Wabash & Erie Canal southwest of Fort Wayne in 1869. A dam was constructed across the canal prism in Fort Wayne and boats continued to run on the (Wabash) Miami & Erie Canal for 6-8 years until Indiana abandoned the canal for good.

Recently Craig Berndt found an 1873 newspaper article that provides another clue in the St. Joseph Feeder’s history. Proposals were being accepted for bridge building, one of which was for a swing bridge across the feeder at St. Marys Avenue. This proves the feeder was in use at that time. A swing bridge would allow for boat passage. If the feeder had not been in operation they would have built a regular road bridge.

One of the feeder dam’s abutments was rebuilt in 1873. Its headgates were rebuilt around 1875.

The feeder dam collapsed in 1877 and had to be rebuilt as did the aqueduct over Spy Run creek on the feeder canal. The cost of repair was $6,000. This is probably when the dam’s abutments were built of concrete.

In 1879 the St. Joe Feeder was considered for a water supply when some Fort Wayne businessmen proposed building a reservoir on the south side of town. However, Spy Run Creek was chosen instead.

The feeder appeared to be of little use until the Jenney Electric Light and Power Company (forerunner of General Electric) decided to use the portion of the feeder between Spy Run Creek on the south to where Spy Run Avenue and North Clinton Street merge on the north. Jenny’s contract with the city for electric street lighting was up for renewal. They decided to use canal water to drive hydraulic turbine-generators to create power. The canal water was then released into the St. Joseph River near the French (Centlivre) Brewery, which was located between the St. Joseph River and the St. Joseph Feeder Canal where present day Clinton Street and Spy Run Avenue intersect. The brewery used the feeder canal for bringing in supplies and shipping out its beer.

A contract between Jenney and Fleming, Bass and Millard Simons (Millard had inherited from Oscar Simons) was signed on November 26, 1887 for the feeder canal water. The contract for the electric power was signed between Jenney and the city in 1888. They planned to not only supply the direct current for street lights but also furnish alternating current for incandescent lighting inside public and private buildings. This sale was mentioned in the Fort Wayne Gazette on November 26, 1888 and talked about the building of a “dam or breakwater on the feeder dam farm” with work to commence on a new hydro-power station that spring. On August 10, 1888 Jenney announced having ordered a 600 horsepower steam engine from the Bass Foundry to be installed on November 1, 1888 and that the power house on Spy Run Avenue would soon be open. They assured everyone there would be no interruption in power. This power house grew to nine boilers by 1902.

On September 24, 1888 Jenney purchased five lots north of Kamm Street and west of Spy Run Avenue for a new power station. One year later Fort Wayne Water Power Company purchased all the lots except one shy at Randolph Street on the north to North Barr Street on the west. There they dug a large basin, filled it with canal water and used it as a reserve in time of water shortage for the power station. This shows that using only a

hydraulic system was not realistic because of an insufficient and irregular head of water from the feeder. The plan was revised to a steam system in 1888 and a supplementary hydraulic system by 1890. It is noted that the steam plant used condensed canal water. The hydraulic system operated until 1907 when the electrical load

created by the increase in population was more than it could handle.

Although this seemed to end the feeder’s usefulness, it was not “done for” yet. Fort Wayne switched from its Spy Run Creek water supply to deep wells around 1890. Some of these wells began failing around 1901 and the feeder was put to use. Connections were replaced linking the city’s filtering basin with the canal water reservoir. The water was siphoned from the basin into a pumping well and then into the city’s mains. The water was so muddy that the mayor had it analyzed.

The March 1904 flood was especially hard on the feeder dam. Ice twenty inches thick was reported above the dam. Then there was a thaw and a flood. The water was 6.5 feet above flood stage. Newspapers kept reporting that a watchman at the dam said it was holding until March 26 when it had water rushing through a muskrat hole. This hole was quickly plugged with sand bags and bales of straw. We aren’t sure this was the end of the feeder dam, but historians believe its final demise came about around 1904-1905. We do know that the feeder dam is not mentioned in the reports of the 1908 flood.

From 1904 through 1907 the feeder dam, feeder canal, Spy Run basin and the hydro-station were owned by different groups at different times. (It is suggested that the attempts at repairing the flood damages by one or some of the companies forced then into bankruptcy or into taking out mortgages.) On August 4, 1908 the Fort Wayne Power Company sold the feeder canal, dam, basin station and the mortgage of Gold Bonds on them to the Fort Wayne & Wabash Valley Traction Company.

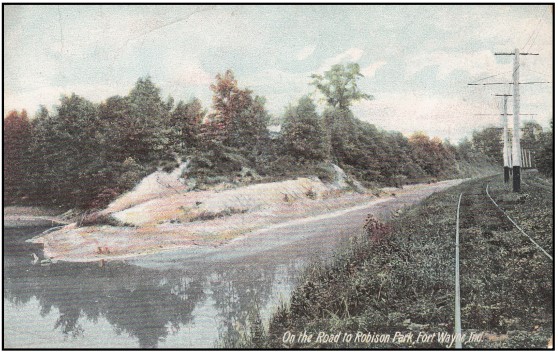

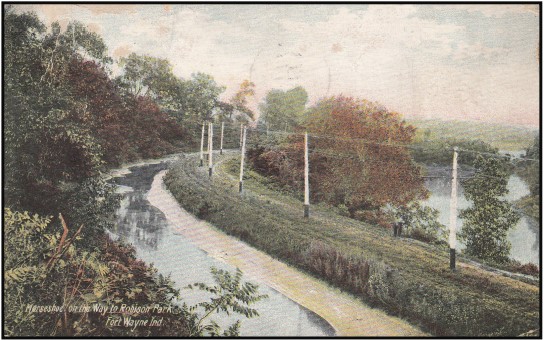

Previously the Fort Wayne Power Company had leased the old feeder tow path right-of-way from the French Brewery to the feeder dam for a double track trolley. This sale allowed the Fort Wayne and Wabash Valley The St. Joseph Feeder Canal left the St. Joseph River in the background and proceeded to the guard lock location in the foreground as seen by the CSI tour on April 5, 1997.

Traction Company, which operated a trolley line on the right-of-way, to continue in business. Finally, the Wabash and Erie Canal and the St. Joseph Feeder dried up.

Robison Park was an amusement park built on the Swift farm, along the St. Joseph River, located near the origin of the feeder canal just above the dam. The dam backed up a pool of water twelve miles upstream making it a recreational water way. The reservoir at the east end of the dam was ideal for boating activities. It was opened in 1896. Originally the only way of reaching the park was by purchasing a ticket and riding the interurban (trolley). The park had a steam powered boat to take visitors for a ride. However after the 1904 flood and the damage to the feeder dam, the pool of water at the dam was not great enough for larger boats and the concession resorted to renting canoes. Robison Park operated through 1919.

Later the right-of-way was sold for utility power lines that were set in the feeder’s bed. These may be followed from the junction of Spy Run Avenue and North Clinton north to North Pointe Woods where Robison Park once was located. Following the feeder prism we are reminded that water does not run up hill but flows from the highest to lowest point. The Wabash and Erie Canal summit was at the feeder dam on the St. Joseph River north of Fort Wayne.

Note the power lines and tracks for the trolleys.

Although few remnants of the St. Joseph Feeder Canal remain today, its history is becoming more complete through research by Canal Society Investigators. Become a canal sleuth and see what you can add to Indiana’s canal history.

Click here to return to the Table of Contents

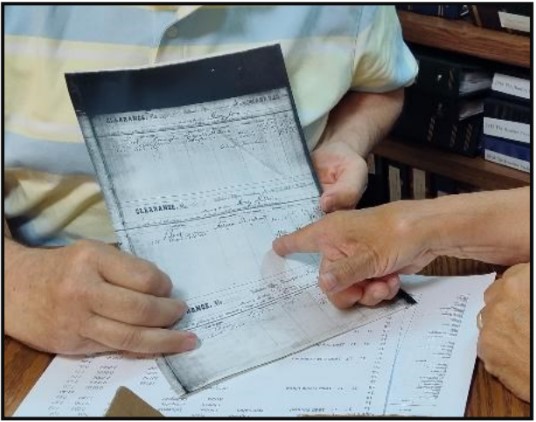

Creating A Data Base Of Boat Clearance Records

some of the work he has completed of putting photo copied

canal boat clearance records into a data base.

CSI member Lowell Griffin of Ft. Wayne, Indiana has taken on the project of creating a database of Wabash & Erie Canal boat clearance records found in the Fountain County courthouse in Covington, Indiana. Once completed it will be a great tool for learning more about what was being shipped on the canal, the names of canal boats, owners and captains, how record keeping changed over the years, etc.

Long in coming, this project began after CSI’s fall tour on October 28, 1995 when 84 members toured the Fountain County courthouse and saw the canal clearance record books there. Covington had been one of the toll collection points for the canal. Somehow the county retained these books when all of the records were called in by Indiana after the canal ceased to operate. Later the returned recalled books were housed in the Indiana State Archives in Indianapolis, but Covington still retained theirs.

Three or more records are found on each page.

On each record the boat captain signed his name on the

bottom right to verify the document was correct.

Since it is difficult to travel to Indianapolis and have limited time to use the archives’ records, CSI headquarters saw an opportunity to get copies of the Covington records for CSI. One book covers May 1846-October 1855 and the other one the period from November 1860-September 1864. CSI president, Bob Schmidt, contacted Fountain County Recorder, Mary Ann Martin, and gained permission to use their record books and copier for a small fee if CSI provided the paper and did the copy work. Bob and Carolyn Schmidt spent six hours a few weeks later copying the books and numbering the pages.

These copies have been used over the years for information about a boat owner or captain for

Canaller At Rest columns, for illustrations of what a clearance record showed, for examples of items shipped by canal, etc. However, the handwriting on these records was difficult to read and sorting through all of them to find a certain name, etc. was very cumbersome. CSI headquarters always wanted to find someone to create a data base, but no one was found who had a desire to do it until recently. Once finished we will be able to sort different things out of the base.

Click here to return to the Table of Contents

Canal Clippings From Old Newspapers

Evansville Daily Journal, Evansville, Indiana

August 9, 1859

A PULPIT JOKE FOR RAILROAD AND CANAL MEN.—A few days ago, says the Buffalo

Commercial, one of our eloquent city divines perpetrated a bon mot in his sermon, which not a

few took, and, among others, a prominent railroad man seemed to appreciate it. He was

preaching upon repentance, “and,” said he, “when the tears of repentance are flowing,

substantial proofs of a degenerated life are expected. Only the tears of deep penitence can wash

away the sins of life, or, I tell you, the heavy freight must go by water.”

Evansville Daily Journal, Evansville, Indiana

August 13, 1859 — The Canal. The Terre Haute Express gives the following information in

regarding the progress of the repairs of the Southern portion of the Canal:

The Canal Association, which was formed last spring, to take the management of the division

from this place to Newberry, has been operating successfully. The main line has been put in

complete order from Worthington to this place—42 miles. Both the navigable “feeder” — eight

miles — are also in good condition. The levels upon this part of the Canal, are now full, the

bars all cleared out, the locks, bridges, and structures in fine order, all ready for the fall

navigation.

There is considerable work to do in repairing the breaks of the last Winter, between Worthington and Newberry, a distance of sixteen miles. The Superintendent is working upon this part of the Canal, with a moderate force, and expects to have it fully repaired, so as to let in the water by the 25th inst. After the completion of the latter portion, the only heavy work remaining to be done, is the repairing of the feeder dam at Eel river; this is a considerable job, and will require the outlay of some six or seven hundred dollars. This done, and the middle division of the Canal will be in better order for navigation, perhaps, than it has ever been.

The Southern Company expect to get their repairs completed up to Newberry by 1st September;

and from that date we may expect Canal navigation to be resumed between this place and the Ohio. The Company northward will also complete their repairs to and at this place by the latter date.

The tolls upon the middle division have been quite light, but are now increasing; and during the next three or four months, will amount to a considerable sum—perhaps sufficient to meet the ordinary repairs, &c.

The following summary of the receipts and expenditures for the past four months — 1st April

to 1st August — upon the division from Terre Haute to Newberry, is obtained from the Secretary.

MIDDLE DIVISION W. & E. CANAL.

Receipts.

| Tolls……………………….. $ 392.76 Subscriptions………… 1,346.50 Water Rents…………… 5.00 |

| Total…………………… $1,744.36 |

The expenditures for repairs and superintendence during the same time has been $1,863.

Evansville Daily Journal, Evansville, Indiana

August 16, 1859 — The water will be let into the lower division of the Canal on Thursday next, as we are informed, and navigation will soon be resumed on the whole line between here and Toledo.

Evansville Daily Journal, Evansville, Indiana

August 18, 1859 — The work on repairing the Canal has been prosecuted with vigor and success, and is now carried to a point so near completion that the water is being let into the lower division or level of about twenty miles, from Pigeon creek at the upper end of the level; and in a day or two we may look to see the Canal full from the city up, and in good boating condition, so that we may shortly expect large shipments of grain to this market from the Wabash Valley; and the fall trade open more briskly than for several seasons before.

The bed of the ditch has been dry, except in spots, for several weeks past. The street sprinklers have run short, the tadpoles dried up and taken legs, and the web-footed fowls betaken themselves to the Ohio [river]. The canal bridges have lately been undergoing repairs; Ingle street has been substantially mended, and entire new ones are in progress at Division street, and at Seventh street, up town.

Evansville Daily Journal, Evansville, Indiana

August 22, 1859

STEAM ON THE OHIO CANAL.—The steam canal boat Enterprise is making regular trips between Zanesville and Cleveland.—The expense is said to be less than one-fourth that of horse power, and not one-fourth of the time to accomplish a given distance. The Captain of the Enterprise has run his boat, towing other boats, at an average of about a quarter of bushel of coal per mile to a boat, in making a trip of one hundred and twenty-eight miles.

Evansville Daily Journal, Evansville, Indiana

August 23, 1859 — The contractors for bouldering Main street, from First street to the Canal, have a couple of boat loads of boulders at the wharf, which they were busy unloading yesterday. We learn that they have some fourteen barges yet to bring down the river. The boulders are procured at some point above Louisville. The contractors will have to push things, or the mud will catch them in the midst of their labors.

Evansville Daily Journal, Evansville, Indiana

August 25, 1859 — A cheap and efficient dredging machine has recently been invented and put in operation at Indianapolis, which, it is said, will remove obstructions from the bottom of a stream to any desirable depth. It does the work of fifty men at a cost of only $5 or $6 a day. It is adapted to deepening canals and removing bars in the Ohio.

Evansville Daily Journal, Evansville, Indiana

August 26, 1859 — The water is coming slowly into the canal, and we expect to see business brightening up in that part of the city. When this section of the canal is ready for navigation, boats can run through to Toledo with less difficulty than has been known for a great length of time.

Evansville Daily Journal, Evansville, Indiana

August 29, 1859 — WOOD.—Lutz, on the canal at the intersection of Walnut street has a good stock of wood now on hand;—but he will have a better supply when the canal is navigable. It can be had in cord wood length or sawed for stoves, and with good measure.

Evansville Daily Journal, Evansville, Indiana

August 30, 1859

NEW YORK STATE CANALS.—The decline in business upon the Erie Canal has been so great this season as to create a serious alarm that it will not much longer be able to sustain itself as a “paying institution” to the State. The receipts of flour from the opening of the canal in 1859 up to the third week in August figure up 203,400 barrels, against 955,900 barrels for the corresponding period of 1858; of wheat 707,900 bushels, against 5,061,300; of corn, 1,522,300 bushels, against 2,863,800; and of barley 150,300 bushels, against 392,100. Reducing the wheat to flour, the deficiency in the receipts of 1859 as compared with 1858, would be 1,623,200 barrels. The disparities for the third week in August are still more striking. The receipts of flour were but 5,900 barrels, against 71,000 in 1858; of wheat, 28,300 bushels, against 134,700; of corn, 72,300, against 310,000; and of barley, not a bushel at all, against 8,900 bushels in 1858.

This decline in business upon the canal is attributed to the low rates of freight upon the competing lines of railway, which—as it is said—have been carrying freight at less than the cost of transportation. This competition has undoubtedly withdrawn a large amount of business from the canal, but a large part of the loss is to be attributed to a decline in the shipments of produce from the West. When the accounts are made up for the year, the deficit in the amount of Western shipments will be found to be greater even than it has been estimated. The New York Herald thinks that, unless something be done to relieve the canals from the heavy costs of State management, they will have to go the way of the Pennsylvania public works, which cost the State forty millions of dollars, and were sold to a private corporation for seven and a half millions.

Evansville Daily Journal, Evansville, Indiana

August 31, 1859 —The Canal. There are now two and a half feet water in the Canal from here to the Reservoir, 31 miles from the city. Boats are running from here to Millersburg with freight. One arrived on Sunday with120 bbls. of flour, and departed on Monday with a full freight of merchandize.

The work at the [Pigeon] Summit will be completed to-morrow, when the water will be let in from Petersburg. Beyond that point the water is already running in, and all the line will be navigable by the 6th of September, and there is a prospect of its opening with a good business.

Evansville Daily Journal, Evansville, Indiana

September 19, 1859

MINING CANALS IN CALIFORNIA.—Mr. Greeley of the N. Y. Tribune gives the following description of the canals for supplying water to the miners in one of his letters from California:

These canals are a striking characteristic of the entire mining region. As you traverse a wild and broken district, perhaps miles from any human habitation or sign of present husbandry, they intersect your dusty, indifferent mind, or carried in flumes supported by a frame work of timber twenty to sixty feet over your head. Some of these flumes or open aqueducts are carried across valleys each a little or more in width. I have seen two of them thus crossing side by side. The canals range from ten to sixty or eighty miles in length, and are filled by damming the stream wherefrom they are severally fed, and taking out their water in a wide trench, which runs along the side of one bank, gradually gaining comparative altitude as the stream by its side falls lower in its canyon until it is at length on the crest of the headland or mountain promontory which projects into the plain, and may be conducted down either side of it in any direction deemed desirable.

I think several of these canals have cost nearly or quite half a million dollars each, having been enlarged and improved from year to year as circumstances dictated and means could be obtained. One of them originally constructed in defiance of sanguine prophecies of failure, returned to its owners the entire cost of its construction within three months from the date of its completion. Then it was found necessary to enlarge and every way improve it, and every dollar of its act[ual] earnings for the next four years was devoted to its perfection. In some instances, the projectors exhausted their own means and then resorted to borrowing on mortgage at California rates of interest; I believe nearly or quite every such experiment resulted in absolute bankruptcy and a change of owners. Water is sold by them by the cubic inch—a stream four inches deep and six wide, for instance, being twenty-four inches for which, at fifty cents per inch, twelve dollars per day must be paid by the taker. A head of six inches depth of water in the flume above the top of the aperture through which the water escapes into the miners’ private ditch in flume—is usually allowed. The price per day ranges from twenty cents to a dollar per inch, though I think it now seldom reaches the higher figure, which was once common. Were the supply twice as copious as it is, I promise it would all be required; if the price were somewhat lowered by the increase, I am sure it would be. Many works are now standing idle solely for want of water.

Evansville Daily Journal, Evansville, Indiana

September 23, 1859

THE LARGEST GATE IN THE WORLD.—A monster gate for the Sault Ste. Marie Canal is nearly completed at Newport, thirty-five miles above this city [Detroit]. It is 82 feet wide, (that being the width of the canal,) 311⁄2 feet deep, and thirty-two inches thick. The timber used in its construction, cut into inch boards, would measure about one hundred and twenty thousand feet! It is believed to be the largest gate in the world. If there is any doubt on this point, its weight, from the immense quantity of iron attached to it, will throw all competitors in the shade, there being about forty tons of iron used in binding it. It will be finished some time this week, when it will be taken to pieces and sent forward to its destination.

This immense piece of work is being built for the contractors, Messrs. Holmes & Clark. The master builder of the wood work—every particle of which is oak—is that skillful and painstaking mechanic, Mr. Steward McDonald, whose name is an ample guarantee that the work is faithfully performed.—Detroit Tribune.

Evansville Daily Journal, Evansville, Indiana

October 4, 1859

CANAL NOTICE.—The Board of Managers of the Southern Canal Company, will meet at the Secretary’s office in Geo. Foster & Co.’s building, on the [Wabash & Erie] canal, on Tuesday evening, the 4th inst., at half past 6 o’clock, P.M. By order of the Board.

W. D. DOWNEY, Sec’y.

Evansville Daily Journal, Evansville, Indiana

October 4, 1859

CANAL NOTICE.—The annual election of a Board of Managers for the Southern Division of the Wabash & Erie Canal will be held at the Court House (in Evansville), on Wednesday, the 5th inst., between the hours of 6 and 10 P.M. By order of the Board.

W. D. DOWNEY, Sec’y.

Evansville Daily Journal, Evansville, Indiana

October 8, 1859

Canal Election. — Pursuant to previous notice, a small majority of the stockholders of the Southern Division of the W. & E. Canal met at the Court House, in Evansville, on Wednesday evening, the 5th inst., at 7 o’clock, for the purpose of electing five Managers for the ensuing year.

The meeting was organized by Wm. Hawthorn taking the chair, and Wm. D. Downey Secretary.

On motion of Judge Foster, the Secretary of the Board of Managers was called upon to read the report of the receipts and expenditures on the Southern Division of the W. & E. Canal, from the first of April up to the first of October, 1859, being the time the Company has had said portion of the Canal under control. The report was read and received.

On motion, the meeting proceeded to the election of Managers.

The following gentlemen were nominated as candidates before the voters of the house.

M.A. Lawrence, Geo. Foster, of Evansville; L. Grant, of Millersburg; Wm. Hawthorn, of Petersburgh; and D. A. Bynum. The following was the result of the first ballot:

For Lawrence, 65; Foster, 86; Grant, 74; Hawthorn, 86; Bynum, 82; R. Barnes, 22. Therefore,

Resolved, That the following gentlemen be declared by the Chairman, as unanimously elected Managers of the Southern Division of the W. & E. Canal:

M. A. Lawrence, Geo. Foster, L. Grant, Wm. Hawthorn, and D. A. Bynum.

On motion the proceedings of this meeting be published in the city papers.

On motion, the meeting adjourned.

WM. HAWTHORN, Chm’n WM. D. DOWNEY, Sec’y.