Index:

The Muskrat: Destroyer of Canal Banks

By Carolyn I. Schmidt

Although the song “Muskrat Love’ sung by The Captain and Tennille portrayed muskrats as cute, cuddly animals that frolicked and proposed marriage while being muzzle to muzzle, old Indiana histories and government reports give us an entirely different prospective on them. Muskrats really were and still are enemies of canals in Indiana and elsewhere.

Muskrat (Ondatra), called musquash by Native Americans, is an aquatic rodent that has a shiny brown outer coat and dense undercoat of fur, a tail that is flattened on either side, and partially webbed toes on its hind feet. It is between 10-14 inches long excluding its 8-10 inch tail, measures about 5 inches at its shoulder, and weighs 2-3 pounds. It secretes musk through its glands that is used to make perfume. It was once hunted for its pelts. It has several litters of 2-6 young each season. It spends most of its time in and around bodies of freshwater such as rivers, lakes, ponds, canals, etc.. It may build a reed hut in a marshy area, but it usually digs a burrow in a steep bank above the water line that has an underwater entrance.

Muskrat (Ondatra), called musquash by Native Americans, is an aquatic rodent that has a shiny brown outer coat and dense undercoat of fur, a tail that is flattened on either side, and partially webbed toes on its hind feet. It is between 10-14 inches long excluding its 8-10 inch tail, measures about 5 inches at its shoulder, and weighs 2-3 pounds. It secretes musk through its glands that is used to make perfume. It was once hunted for its pelts. It has several litters of 2-6 young each season. It spends most of its time in and around bodies of freshwater such as rivers, lakes, ponds, canals, etc.. It may build a reed hut in a marshy area, but it usually digs a burrow in a steep bank above the water line that has an underwater entrance.

Canals were the victim of muskrats, who destroyed millions of dollars worth of Indiana canals in the 1830s by burrowing through their shallow and soft banks. Muskrats loosened the material with their front feet and cast it up with their hind feet. Water began to seep through the banks creating bigger and bigger passages until the banks collapsed. Esary said: “Canals were not living up to their promises.”

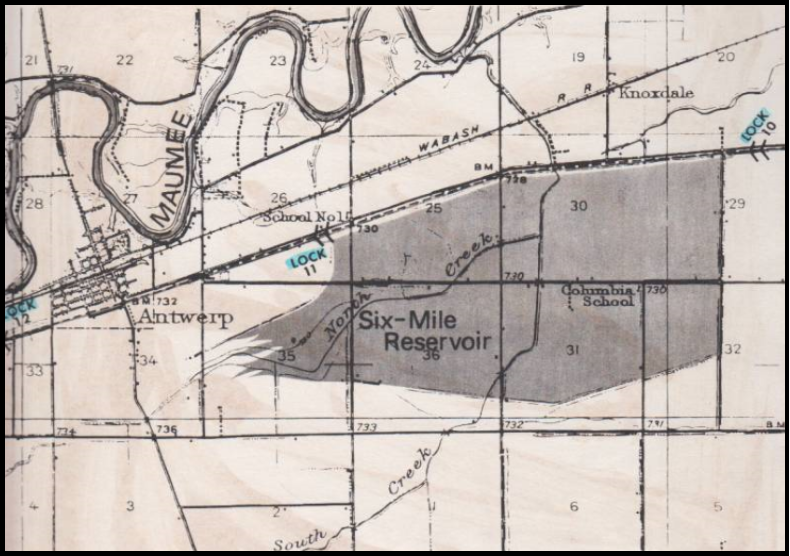

When building the canal reservoirs, the canal engineers took into account the destruction caused by muskrats. The Six-Mile Reservoir for the Wabash & Erie Canal was located about 1½ miles east of Antwerp, Ohio, and fed the canal beyond Antwerp. It was surveyed in 1826 at the same time as the canal, but actual work wasn’t started until 1840 and completed in 1843. The reservoir measured about 2½ miles from east to west, and about 1½ miles north and south, covering 3,600 acres permanently and as much as 14,000 acres when full.

Its banks were about eight feet high. In their construction, first a layer of oak planking was set up edgewise [like a fence] on the center line of the bank. This “Sheet piling” as it was called, helped to make the bank watertight, as well as resisting the efforts of burrowing animals such as groundhogs and muskrats.

Next, earth was thrown against the sheet piling from both sides to build up the banks. Then, a layer of clay was placed on the inside slopes of the reservoir, water was mixed with the clay, and oxen were driven back and forth over it. The hooves of the animals compacted or “puddled” the clay mixture turning it into a cement-like layer that would resist seepage. A modern machine called a “sheep’s foot roller” is used today for the same purpose as were the oxen.

Next, earth was thrown against the sheet piling from both sides to build up the banks. Then, a layer of clay was placed on the inside slopes of the reservoir, water was mixed with the clay, and oxen were driven back and forth over it. The hooves of the animals compacted or “puddled” the clay mixture turning it into a cement-like layer that would resist seepage. A modern machine called a “sheep’s foot roller” is used today for the same purpose as were the oxen.

Six-Mile Reservoir was between Locks 11-10 on the Wabash & Erie Canal. The dam with sheet piling was on its east end before Lock 10.

Although the sheet piling helped maintain the reservoir dams, the actual canal banks had nothing to keep the muskrats from tunneling through. They did so much damage that a bill concerning muskrats was recorded in the Senate Journal of Indiana in 1844 as follows:

Mr. President:

The committee on canals and internal improvements, to whom was referred a resolution of the Senate, on the subject of encouraging the killing of muskrats on the Wabash and Erie canal, have had the same under consideration, and have directed me to report it back, with the accompanying bill, and recommend its passage:

No. 171. A bill to encourage the killing of muskrats on the Wabash and Erie canal;

Which was read, and,

On motion by Mr. Chapman of Laporte,

The rule of the Senate was suspended and the bill read a second time.

Mr. Chapman of Laporte moved to amend the bill by striking out the word “scalps,” where it occurs, and insert, in lieu thereof, the word “skins;”

Which was not agreed to.

The bill was then ordered to be engrossed.

No. 171. A bill to encourage the killing of muskrats on the Wabash and Erie canal;

Mr. Ewing moved to recommit the bill to a select committee, with instructions to strike out so much of said bill as provides for giving a premium for ears, and render the language of the bill more precise.

Mr. Lane moved to amend the instructions so as to require that the ears shall always constitute a part of the scalp.

The motion to recommit with the instructions, as amended, was then agreed to.

Ordered, That the committee consist of Messrs. Ewing, Reyburn, and Chapman of Laporte.

On motion by Mr. Standford,

The order of business was suspended to take up the following [another bill]

No. 171. An act to encourage the killing of muskrats on the Wabash and Erie Canal;

With two amendments

And,

On motion by Mr. Reyburn,

Ordered, That the bill lie upon the table.

On motion of Mr. Orth,

The Senate concurred in the amendment of the House to joint resolution of the Senate.

Paul Fatout wrote in Indiana Canals: “Trouble was continual [on the Wabash & Erie Canal]. Elusive water seeped out of minute fissures that, if not plugged, were likely to become wide breaches. Freezing and thawing shifted the mobile earth; burrowing muskrats and crawfish aided water to escape. Given an opening, the canal crumbled its banks, and it could be murderous.

The packet Kentucky, caught by the swift current boiling through a big break near Logansport, snapped her mooring lines and sailed helplessly out into the woods, where she crashed bow on against a tree, swung around, hit another with her stern, broke in two and spilled passengers into the flood. Three men were drowned.”

The Whitewater Canal also experienced muskrat problems. In Mammals of Indiana “Butler noted — along the Whitewater Canal he found that each bank burrow had two openings—usually 18-24 inches apart. Bank burrows are commonly used and muskrats seem to prefer to construct these burrows in vertical banks,” thus making canal towpaths and berm banks prime targets.

Fox reports: “Caleb Jackson was superintendent of the [Whitewater] canal for a time, and an interesting joke on him is related in this connection by George Callaway, of Milton. One of the superintendent’s duties was to see that the canal was in good condition as the banks were being badly damaged by muskrats. Jackson offered ten cents a piece for their tails. Accordingly, the boys of Milton arranged this scheme: One of them would take some muskrat tails to Mr. Jackson, receive his money and go away, but soon turn around and stealthily follow Jackson down the canal to see where he threw the tails. When this was ascertained, another boy would get them and repeat the operation, and so on, until all the boys of the village had enough spending money to last them several days. Mr. Jackson finally discovered the plot and afterward threw the tails into the canal.”

Indiana’s Central Canal was also besieged by the muskrats. Dunn reports: “A number of breaks have been due to the burrowing of muskrats, and the canal patrol—the [Indianapolis Water ]company has for years had the bank patrolled daily by two men—is specially charged with the duty of watching for and killing these animals. It has also paid a bounty of five cents for tail tips, and distributed traps free of charge to farmers along the line One would naturally expect fur-bearing animals to be almost extinct in this vicinity, but for the past five years there have been over one hundred muskrats killed annually in this little stretch of canal.”

Thus men called towpath walkers would either walk or ride up and down an assigned portion of a canal to look for muskrat or crawdad holes and leaks and have them repaired before the canal was breached. They were expected to keep a round-the-clock watch, especially when there were severe storms, and had to brave the weather to carry out their duty. The towpath walker also observed the waste gates every ten miles, looking for erosion on the banks. If he could fix it, he did.

Years later Dunn said: “It is practically impossible to maintain a high line canal with earthen banks and wooden locks and dams in a country that is subject to heavy floods, and abounds in burrowing water animals, especially muskrats. The muskrat has a propensity for digging holes through canal banks, and when the water begins running through one of such holes the embankment quickly washes out and the canal is gone, until the embankment is replaced. As an illustration, the seven miles of the Central Canal between Indianapolis and Broad Ripple, of which about one-third is high line, has been washed out repeatedly from this cause… Even in the settled condition of the region, in the five years, 1905-1910, there were more than one hundred muskrats killed in this little stretch of canal.

The muskrat was the object of a study reported in the Scientific American Supplement, No. 522, January 2, 1886 entitled “Observations On The Muskrat” by Amos W. Butler. It is quoted below:

The muskrat (fiber zibethicus CUV.) is very abundant in most localities in Southeastern Indiana. In local distribution it varies in numbers according to the abundance of water and favorable localities for its increase. From all that I can learn, I do not think it is less common than at the time of the early settlement of this region.

These animals soon became acquainted with man and, from experience, learn that his presence assure them a great abundance of food at much less labor than formerly, while, at the same time, their natural enemies decreased in numbers on account of his necessity and pleasure. In some localities, owing to the persecution of a neighborhood of farmers, muskrats are low in numbers and are very shy. In the greater number of places, however, but little attention is paid to their destruction, and in consequence they become very tame, being found within the corporate limits of some of our larger towns. Originally, they had their home in the neighborhood of natural water-courses, but with the system of State improvements which led to the building of our canals there came, in many localities, a change in the life of the muskrats. Upon the completion of the White Water Valley Canal, in 1846, the greater number of muskrats living upon the streams along which it ran sought this artificial waterway, and there established homes. No doubt they soon realized the greater security this canal afforded them from the frequent floods and other dangers they had formerly experienced. At the present time, along that portion of the canal in existence, but few muskrats have sought the neighboring streams whence their ancestors came. When the muskrat changed their residence to the line of the canal, they made new homes in its loamy banks, similar to the ones they had deserted along the riverside. They are found both in our water-power canal [Whitewater Hydraulic canal] and in the swifter streams most numerous where there is a good food supply at the same time near a quiet nook secluded from the prying eyes of some human enemy and his allies. I have noticed them to be exceedingly abundant about the estuaries of creeks whose banks are covered with a luxuriant growth of vegetation.

These animals soon became acquainted with man and, from experience, learn that his presence assure them a great abundance of food at much less labor than formerly, while, at the same time, their natural enemies decreased in numbers on account of his necessity and pleasure. In some localities, owing to the persecution of a neighborhood of farmers, muskrats are low in numbers and are very shy. In the greater number of places, however, but little attention is paid to their destruction, and in consequence they become very tame, being found within the corporate limits of some of our larger towns. Originally, they had their home in the neighborhood of natural water-courses, but with the system of State improvements which led to the building of our canals there came, in many localities, a change in the life of the muskrats. Upon the completion of the White Water Valley Canal, in 1846, the greater number of muskrats living upon the streams along which it ran sought this artificial waterway, and there established homes. No doubt they soon realized the greater security this canal afforded them from the frequent floods and other dangers they had formerly experienced. At the present time, along that portion of the canal in existence, but few muskrats have sought the neighboring streams whence their ancestors came. When the muskrat changed their residence to the line of the canal, they made new homes in its loamy banks, similar to the ones they had deserted along the riverside. They are found both in our water-power canal [Whitewater Hydraulic canal] and in the swifter streams most numerous where there is a good food supply at the same time near a quiet nook secluded from the prying eyes of some human enemy and his allies. I have noticed them to be exceedingly abundant about the estuaries of creeks whose banks are covered with a luxuriant growth of vegetation.

When the canal through this part of this state was destroyed in 1856, the rats disappeared from many places where they had long found a home. Some sought the river where their ancestors had dug their holes in time long past; others gathered into certain parts of the old canal bed which were not permitted to remain unused. One of these portions is now the property of the Brookville and Metamora Hydraulic Company, and is used for the purpose of supplying power to several mills along its banks. This part of the old canal is about fifteen miles long, extending from Laurel to Brookville. It is here that I have become best acquainted with this water loving rodent.

The muskrat prefers its home in banks of loam or light clay, especially when heavily covered by vegetation. It is very exceptional that it occupies gravelly or sandy banks. Advantage has been taken of this fact by the managers of our water-way and by the railroad company. Where they have constructed gravel banks and kept them free from vegetable growth, it is rarely that they are bothered. Trenching the banks and filling in the trenches with gravel has proved of considerable value, while some protection has been afforded by a top-dressing of coarse gravel over an old bank of loam, provided vegetation is not allowed to grow thereon. When these precautions have not been taken, great damage is done each year; the burrows of these animals are continually being enlarged, and caving in cause a leak, or undermine the railroad track, as the case may be.

In early spring the greatest damage is done. With the alternate freezing and thawing at that time of the year, the coverings of these underground passages drop in, exposing cavities of surprising extent to one who does not know the amount of subterranean work this animal is capable of doing. It requires vigilant work of eyes and ears to prevent this caving causing great damage to property. The underground homes of the muskrat in the banks of the canal have each two openings. When the water is at its usual stage, an opening may be found, the upper edge of which is on a level with the surface of the water; another hole may be seen at low-water mark, the top of which is just level with the surface of the water at that stage. These holes are generally from eighteen inches to two feet apart. The passage from these openings lead backward and upward in a very crooked way, as anyone who has attempted to follow them up can testify. These passages end in a large gallery which is the home of the animal. From this chamber a small passage leads to the surface, ending amid a bunch of grass or weeds. By this means the gallery is ventilated. The holes at the surface are known as “air holes.” They are not always found at least I have not in all instances observed them. In heavy ground an “air hole” is always found, while in poorest ground it is as often absent as not. These underground burrows extend into the bank a distance of ten to twenty feet in a straight line as a rule. Instances have been noted where the depth reached was less than the minimum giving above, but such are rare. In localities along small streams which are subject to sudden rises, the distance attained occasionally reaches thirty feet; but in all instances the depth to which these burrows reach depends, in a great measure, upon the size and composition of a bank as well as upon the liability of the neighboring stream to sudden changes of level.

In the abandoned parts of the old canal before referred to, the muskrat built houses for the first time in this part of the State. They were few in number and were confined to wet tracts, the source of whose water supply was springs from the neighboring Silurian hills or in swamps adjacent to the line of the canal. Until within the past three years no [muskrat] houses had been built along the water-power canal between Brookville and Laurel. Each succeeding year I noticed the erection of a few more houses until at this time there are a dozen or more within the fifteen miles just mentioned. Within ten miles of the northern end of this artificial water-way, in the old bed of the canal, have been several [muskrat] houses for a number of years. Whether this house-building habit is caused by some of the house-building muskrats coming from upstream, or whether, from some unknown reason the animals of our own locality have taken upon themselves they ways of some distant ancestor, we cannot say. That muskrats do, from force of circumstances, change their location is a well known fact, and such a change would be perhaps the most logical way to account for the reason for the house-building just mentioned.

I have made careful examination of some of these houses, and herewith present some extracts from my notes on one of them which I consider typical in construction and arrangement. This examination of this house was made in January last [1885] when the ground was frozen, but the more rapid streams had little or no ice upon them. This particular house was built upon the highest part of a piece of marshy ground on a peninsula extending into a stream which passed through the marsh. The end of the peninsula had been dug off to the level of the bottom of the stream leaving a semicircular exposure of land. A part of the base of the house followed the configuration of the edge of this excavation, while the remainder of the foundation rested upon the bottom of the stream. In consequence of this, rather more than half of the house adjoined the water. The house was composed chiefly of swamp grass, sedge, coarse weeds, and mud, while fresh-water algae, small pieces of drift, a few pieces of shingles, and two staves were found among the more common material. The greater part of the mud was in the lower part of the house, and I think was mostly brought in attached to the roots of grass. The ground in the neighborhood of this house was cleared of all vegetation, even on the roots, for some distance. The house was thatched very nicely with weeds and sedge. The ground plan was oval in outline, four feet six inches wide and six feet three inches  long. On the land side the house was two feet six inches high, and on the water side three feet four inches. The whole presented the appearance, in miniature, of an oblong hay rick. The inside was quite irregular. Measurements at the bottom of the chamber showed the greatest length to be twenty-two inches, the least sixteen inches, with an average width of twelve inches. The greatest height measuring from the bottom of the stream was one foot. Six inches from the bottom a shelf was found running from the left of the entrance and above the top of the water. This shelf was twelve inches long and eight inches wide, and ranged from six to eight inches in height. It was arched over very neatly with drift and coarse weeds. At a point farthest from the center of the chamber, immediately over the shelf, was a passage leading upward toward the side of this house. While it did not penetrate the wall, it passed through the more compact portion and enabled the inmates to obtain air. Entrance was had through a covered way from and beneath the water without to the center of the house, where it terminated in a mass of fine grass and mud, through which was a funnel shaped opening to the interior. This house was completely destroyed; within a week after its destruction the muskrats had erected a new house upon the site of the old one. In securing material for this they had used the remnants of the ruined house and had cleared a much larger space of ground within its withered vegetation. In outline the new house resembled the old one, but it was nearly double the size of the ruined structure. There are peculiarities in the shape of many houses, but that which I have described appears typical in form and in interior arrangement of these structures in this vicinity. Some of these houses are built at a time when the water is low, and as the fall rains swell the streams the rats are compelled to reconstruct their buildings raising the top above the highest level of the water. I knew a muskrat to try this plan last year. It built its house within the banks of an ice-pond which was almost dry. As the water was turned on, late in the fall, the owner [muskrat] tried by making the house higher, to keep a portion of the structure above the encroaching water. An increase in altitude of six feet was too much for the industrious animal; by the time half of this height was reached he gave up the work. Occasionally, instead of laying a part of the foundation out of the water, the house is begun entirely within the water. At times I have known a hollow which had a lower opening beneath the water to be used. The stump being covered over and some grass and other material placed around the base, it required close observation to recognize the framework of the structure. I have known these animals to take possession of a barrel which stood on its end in the water, and after covering it over so as to almost hide it, to give up this work and erect a dwelling without the substantial assistance such an article would afford.

long. On the land side the house was two feet six inches high, and on the water side three feet four inches. The whole presented the appearance, in miniature, of an oblong hay rick. The inside was quite irregular. Measurements at the bottom of the chamber showed the greatest length to be twenty-two inches, the least sixteen inches, with an average width of twelve inches. The greatest height measuring from the bottom of the stream was one foot. Six inches from the bottom a shelf was found running from the left of the entrance and above the top of the water. This shelf was twelve inches long and eight inches wide, and ranged from six to eight inches in height. It was arched over very neatly with drift and coarse weeds. At a point farthest from the center of the chamber, immediately over the shelf, was a passage leading upward toward the side of this house. While it did not penetrate the wall, it passed through the more compact portion and enabled the inmates to obtain air. Entrance was had through a covered way from and beneath the water without to the center of the house, where it terminated in a mass of fine grass and mud, through which was a funnel shaped opening to the interior. This house was completely destroyed; within a week after its destruction the muskrats had erected a new house upon the site of the old one. In securing material for this they had used the remnants of the ruined house and had cleared a much larger space of ground within its withered vegetation. In outline the new house resembled the old one, but it was nearly double the size of the ruined structure. There are peculiarities in the shape of many houses, but that which I have described appears typical in form and in interior arrangement of these structures in this vicinity. Some of these houses are built at a time when the water is low, and as the fall rains swell the streams the rats are compelled to reconstruct their buildings raising the top above the highest level of the water. I knew a muskrat to try this plan last year. It built its house within the banks of an ice-pond which was almost dry. As the water was turned on, late in the fall, the owner [muskrat] tried by making the house higher, to keep a portion of the structure above the encroaching water. An increase in altitude of six feet was too much for the industrious animal; by the time half of this height was reached he gave up the work. Occasionally, instead of laying a part of the foundation out of the water, the house is begun entirely within the water. At times I have known a hollow which had a lower opening beneath the water to be used. The stump being covered over and some grass and other material placed around the base, it required close observation to recognize the framework of the structure. I have known these animals to take possession of a barrel which stood on its end in the water, and after covering it over so as to almost hide it, to give up this work and erect a dwelling without the substantial assistance such an article would afford.

I find the muskrat lives, the greater part of the year, in its sinuous galleries in the banks of our streams. Each autumn new houses are built or old houses repaired, but these are only occupied when the surrounding streams are locked in a sheet of ice. At such times it is by no means uncommon to find several representatives of the species living in harmony within one of these winter homes. I am convinced that in this vicinity one brood of muskrats is regularly brought forth each year. There are, in all probability, occasional exceptions to this rule, when perhaps two and even three broods are born. Mating takes place late in February or early in March, depending upon the condition of the weather, and continues about three weeks. This year these animals were first noted as mating on March 10. At this season the female utters a hoarse squeal by which the males are attracted. The period of gestation is about six weeks. In April or early May the young are brought forth; from four to six helpless and hairless little creatures may then be found by the persevering investigator far within the subterranean home within a nest of grass and other soft vegetable growth. The young remain in the nest until they are about half grown, unless their home be flooded, when they often perish, but in some instances are rescued by the mother. Mr. E. R. Quick relates one instance when during a flood, July 8, 1873, he saw a female muskrat swimming along in the muddy water with five young about the size of a full-grown house rat, holding onto tufts of the mother’s hair with their mouths while she made her way slowly and cautiously along the shore; carefully she avoided all obstructions and swift water, seeking a shelter for her precious tow. Some boyish enemy perceiving the homeless family, threw a stone which struck the mother and scattered the young. The latter apparently knew nothing of diving and but little of swimming; with difficulty they gained the shore and while seeking the protection of some reeds a part of them were caught. I have never found the young caring for themselves until after the beginning of July. In September, a few years since, a litter of young was taken from a nest in the canal bank. They were not over one-third grown. This record I have always considered as referring to a second or perhaps a third brood, and is my only note that would indicate a plurality of broods.

During the rutting season the grunts of the males answer the squealing of the female, the noise of scuffles between the males, the continuous splashing made by the animals in the water fill the air, in the vicinity of one of their favorite ponds, with sounds which would surprise one who was not familiar with the neighborhood of a muskrat’s home on a warm night in early spring. At this time of the year they are seen during daylight more than at any other, sometimes even deigning to show their love making to inquiring eyes.

Muskrats are naturally herbivorous. They feed upon land and water plants alike, in some instances using roots, stems, and fruit. They are noted enemies of the “bottom” farmer. In his fields it is that corn grows most plentiful, and upon this cereal muskrats love to feed. They eat corn at any time after it is planted, taking the seed from the ground or the young plant from the furrow. The greatest damage is done after the ear is well formed. “Roasting” ears appear to be a favorite article of food with them. From this time until the corn is gathered, nightly visits are made to the neighboring corn field, where the stalks are cut down and sometimes carried to their homes, but more frequently the juicy ear is the only part taken. At times streams near corn fields seem covered with floating stalks, the result of the muskrat’s nocturnal forays. As the corn becomes hard, it is frequently a difficult question for them to tell how they will get the grains off the cob as easily as formerly. They evidently master the question in some instances, for I have known them to deposit the flinty ears in a stream for two or three days until the grains become soft, when they could be easily removed. It seems strange that an animal having teeth of the cutting power those of the muskrat possess, should seek to do this, but in all probability, the teeth, from continual eating of vegetable food throughout the summer, become tender, and are unable to cut hard grains of corn with ease. This is the case with many domestic animals in autumn when fed on corn after some months of pasture life. Muskrats are very fond of parsnips, turnips, and apples. They frequent apple orchards and turnip patches, near their houses and make use of much of the farmer’s abundant crop of these articles. When snow, which had lain on the ground for some time, melted, I have observed that plats of grass near the water’s edge had been eaten bare by these animals while they were confined to such diet as they could find beneath the ice. Their food is not entirely vegetable; in winter and in early spring they subsist in a great part, upon the flesh of river mussels. Many a winter morning have I found a number of well cleaned shells of the more delicate mussels upon the ice near swift running water. I have never been able to satisfy myself that this food was used by them at any other time of the year. Neither do I believe that this material was originally so used. It is very probable that, owing to the scarcity of suitable vegetable food, they have been forced to include the meat of the mussel among their articles of diet—largely on account of its abundance near their watery haunts, and also on account of the ease with which it is obtained. Such change of food has not occurred in this region within historic time, perhaps, but it is evident that formerly, when there were few mussels in these rivers, not so many of them were eaten. With the conditions favorable to their [mussels] development produced by our canal, mussels multiplied very rapidly, and in proportion to their increase in numbers, the muskrat increased his mussel-eating. Records of this are preserved in the banks of the canal; alternate deposits of shells, cleaned by the muskrat, and of sediment may be seen in many localities reaching to the depth of two feet below the present bed of the stream. Under these same piles of bivalve remains the muskrat leaves the remains of most of the mussels it eats. I have never known the muskrat to eat univalve mollusks. I have identified the following shells as forming the principal part of its bivalve food in this vicinity: Anodonia plana Lea, A. decora Lea, A. imbecillus, Say, Unio luteolus Lam., U. parvus Barnes, Margaritana rugosa Les, and M. complanata Lea, all common in proportion to their comparative abundance. In some localities I found the young of Unio occidiens Lea, but not very common. In another locality where Unio lachrymosus Lea, is the prevailing species, I found its shells forming the bulk of the refuse near the muskrat homes. In this same locality I found examples of Union plicatus Le S. and U. multiplicatus Lea, but were not common. The young of heavier shells are to be found as commonly, in proportion to their abundance in the adjacent water, as are the remains of the more fragile species. I have estimated that about one-half of the mollusks eaten are of the three species Anodonata. I was surprised at the comparative abundance of the remains of the Margaritana rugosa Lea in these piles of shells. This species is considered to be rather rare, but their shells are found as frequently there as are those of some of our more common species. From this fact I think the muskrat prefers the flesh of this species to that of others that might be more easily taken. I have at times found examples of living Unios among these heaps of shells; whether these had been brought by the rats, or whether they had sought, of their own accord, a dwelling place among the remains of their dead ancestors, I cannot say. The means by which the muskrat secures the body of a mussel has been frequently discussed. I think, from my observations, there are three ways in which these shells are opened. With many species I notice that the foot is very slowly withdrawn within the covering when the shell is handled. When such shells are taken, it is very easy for the muskrat to insert its paws or long teeth between the valves and tear them asunder. The remains of some species show evidence of the cutting power of their enemy’s teeth—the edges are broken; when this is done, it would be very easy for the muskrat to find a sufficient opening to secure the animal as in the preceding instance. By those two ways the more fragile may be opened; the heavier species which are occasionally found nicely cleaned about the opening of the muskrat’s home could not be opened in this manner. I have on several occasions noticed these larger mussels lying on the bank of a stream near a muskrat hole, and within a few days they disappear. The only way in which I can see the muskrat could obtain the body of one of these larger mollusks is by leaving the animal out of the water until it becomes weak or until it dies, when the valves could be easily separated. Muskrats at times eat the bodies of dead animals. The remains of ducks, geese, chickens, fish, and even in one instance a turtle, have been noted as forming a part of their food. The farmers of the lowlands ascribe to the muskrat a love for young ducks, but I think the greater part of their loss in this particular is referable to turtles.

The muskrat is largely nocturnal in its habits. On cloudy days and occasionally late in the afternoon one may be seen along some quiet stretch of water, seeking food or looking for its mate. It is not much at ease on land, although when pursued it moves over the ground at an ambling gate with some degree of rapidity. It is an expert at swimming and diving. Before diving it appears to inflate its lungs with air and when it disappears remains beneath the water for some time, the course it takes being frequently traceable by rising bubbles of air. When surprised, it plunges into the water suddenly without the necessary supply of air, and is forced to come to the surface in a very short time. When frightened, it generally seeks its hole, but such is not always the case. In open water it dives to a considerable depth and I have noticed it passing through shallow water, apparently running upon the bottom. Under the ice it may be noticed, at times, swimming quite close to the surface of the water. It appears disinclined to dive in muddy water. Upon several occasions, when our streams have been swollen, I have attempted to make one dive by stoning it, but generally without success; sometimes it would dive, but would almost immediately reappear. When our water-courses are covered with ice, the muskrat has regular places of regress and ingress, such places being where, owing to the swift water, ice has not formed or where the ice along the banks of a stream has been broken.

Several methods are employed to capture or to kill muskrats. Many of them are caught by means of steel traps. They are very unsuspicious, and regularly become the victims of their self assurance. A dead fall is frequently used with some effect. It is generally placed over a well worn runway leading to a favorite feeding ground. Many muskrats are killed by means of poison apples or turnips which are placed in the neighborhood of their burrows. The latter plan is often tried by the farmers of our uplands to kill these animals when they become too numerous in the ditches and smaller streams. A method used with great success by a local water-power company, in winter, is as follows: A barrel with both ends out is placed upright near the bank with about half of its length in the water. Upon the water inside the barrel is placed grass and weeds, and on this foundation the bait, generally a few pieces of parsnip is put. In a few days the animals will become familiar with this new object, and thereafter the barrel may be visited regularly. After a warm night the trapper is reasonably sure of finding some game in his barrel. Sometimes he will find but one or two rats, but more frequently he will catch from three to six, and on one occasion I have known of ten rats to be taken in one barrel in a single night. At mating time, if a female be caught, several males will be taken prisoner in the same barrel in their efforts to become her company. When a rat gets into the barrel, it is impossible, owing to the depth of the water, for it to stand upon its hind limbs to cut a hole in the staves above the water line, and at the same time impossible for it to get out at the top of the barrel. When several are taken the same night a fight generally ensues, resulting in the death of all of the captives, either by the sharp teeth of their companions or by drowning. I have known instances where several of these rats had been captured and killed, but the trapper did not visit this traps for some time; upon his arrival, however, he found but a few heads and bones to tell of the tragedy that had been enacted and of the feast the other muskrats had when the water receded enough for them to enter and leave the barrel. This habit is not uncommon when more acceptable food is scarce. Last spring a muskrat was caught in a steel trap; where the trapper went to his trap next morning, he found another rat eating the dead one; upon examination it was found that the entire right shoulder had been eaten off. Spears are rarely used, but they are sometimes brought into service when the streams are ice-bound to kill the inhabitants of a winter house. Many muskrats are shot in early spring, when the ice breaks up.

Of the enemies of the muskrat, man ranks first and next to him the dog. Hawks and owls are the larger species, foxes, and minks are all very destructive to this animal. The mink is perhaps its greatest natural enemy but fortunately for it minks are rare. The remains of muskrats have, on several occasions, been found in the stomach of large catfish, but the flavor of the food had been so thoroughly imparted to the meat of the fish that it was unfit to eat. The muskrat is at times very ferocious. When cornered by dogs or man, it frequently shows fight; and if pressed too closely is able to do much execution with its sharp teeth.

Muskrats have their pleasures as do other animals; but as their favorite time for sport is after night, we have but little opportunity to become acquainted with them socially. On a warm quiet afternoon they appear to enjoy a sunning in some secluded spot. Their gambols in the water, of a quiet evening, remind me much of the playing of kittens. They may be seen at times, of a moonlight night, chasing each other over some sandbar near their watery home. On the whole the study of their enjoyments is very unsatisfactory, and much of our knowledge of the life history of these animals will be but slowly acquired.

Years later after Butler’s article, Dunn wrote: “An energetic muskrat would dig a hole through the bank, and unless the opening was very quickly discovered, that was the end of the canal for weeks. The company paid a bounty on muskrat scalps for years, on this account, and it never made a more profitable investment. But with all this experience it is doubtful if the American people have yet learned that if you want to make a permanent waterway you must dig it out and not build it up—indeed we have already started on a repetition of the same old absurdity with the Panama Canal. ”

Fatout reported in a chapter entitled “Post-Morten 1874-1900” that “The deserted [Wabash & Erie] canal, uncared-for, grew more down-at-heel as banks eroded and locks fell apart. Hitherto flourishing small towns, like Pittsburg, Lagro, and Roanoke, lost momentum and inhabitants. Fragments of the unused channel became unsightly. An anonymous Logansport scribbler glumly mused upon stagnation so sickly that muskrats turned away in disgust.”

Sources:

Butler, Amos W. “Observations on the Muskrat,” Scientific American Supplement, No. 522, January 2, 1886.

Dunn, Jacob Piatt. Greater Indianapolis: The History , the Industries, the Institutions, and People of the City of Homes. Chicago, IL: The Lewis Publishing Company. 1910.

Dunn, Jacob Piatt. Indiana and Indianans: A History of Aboriginal and Territorial Indiana and the Century of Statehood. Chicao, IL: The American Historical Society. 1919.

Ehrhart, Otto E. “The Six-Mile Reservoir,” Indiana Waterways, Ft. Wayne, IN: Canal Society of Indiana. 1985.

Esary, Logan, Kate Milner Rabb, Wm. Herschell. History of Indiana from Its Exploration to 1922. 1924.

Fatout, Paul. Indiana Canals. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press, 1972.

Fox, Henry Clay, Ed. Memoirs of Wayne County and the City of Richmond, Indiana. Volume 1, Madison, Wisconsin: Western Historical Association, 1912.

Indiana History Bulletin. Vol. 58, 1981.

Journal of the Senate of the State of Indiana During the Twenty-ninth Session of the General Assembly. Indianapolis, IN: J, P Chapman, State Printer, 1844.

Klein, Stanley. North American Wildlife. 1984.

Muskrat (/dnr/fishwild/7477.htm)

Muskrat. The Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th edition. (Encyclopedia.com)

Schwartz. Charles Walsh, The Wild Mammals of Missouri,

Visions of Paulding County: From the Historical Archives of the Paulding County Progress. 2005.

Whitaker, John O. and Russell E. Mumford. Mammals of Indiana. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2009.

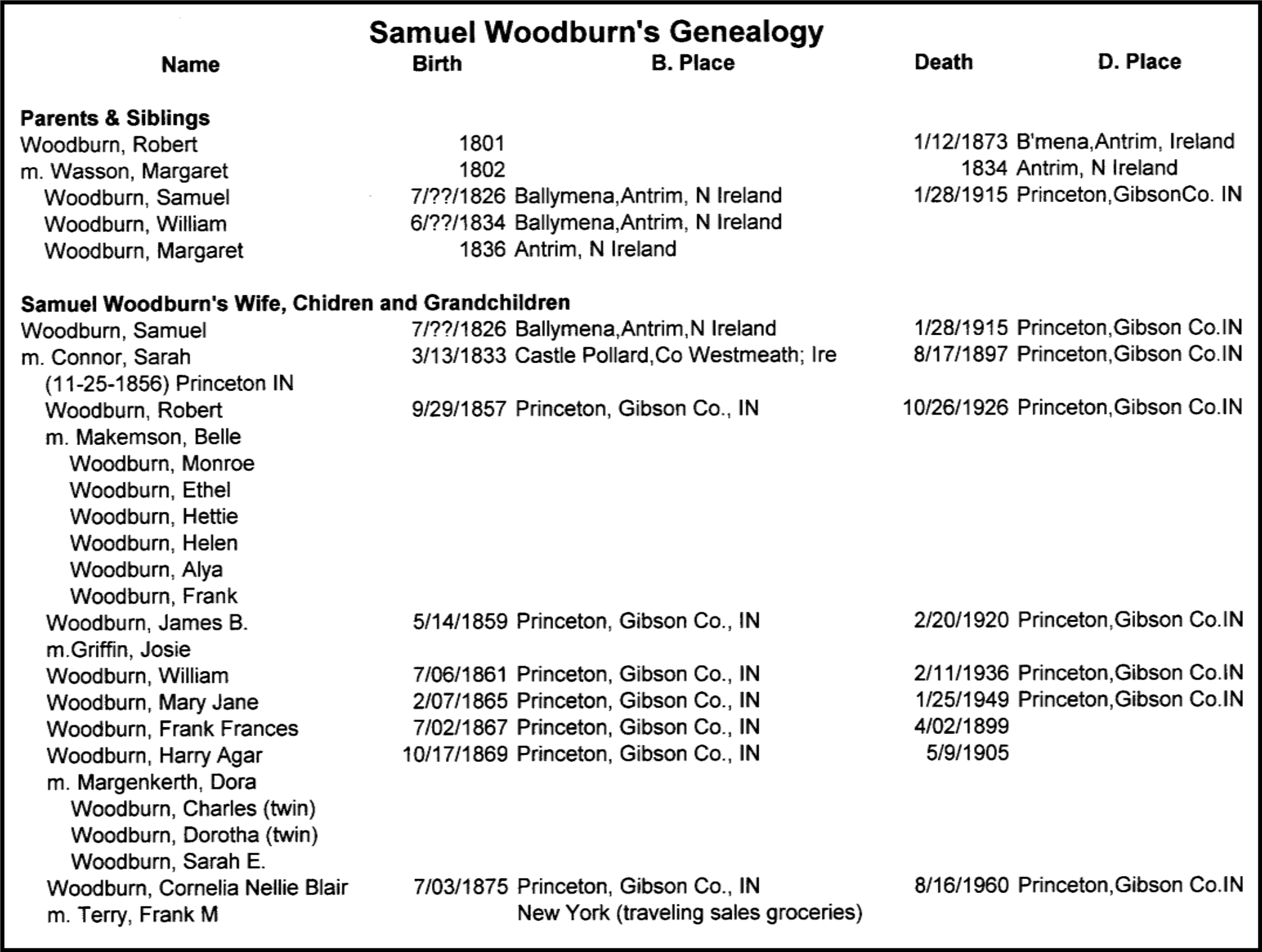

Samuel Woodburn

Find-A-Grave #138710655

By Carolyn & Bob Schmidt

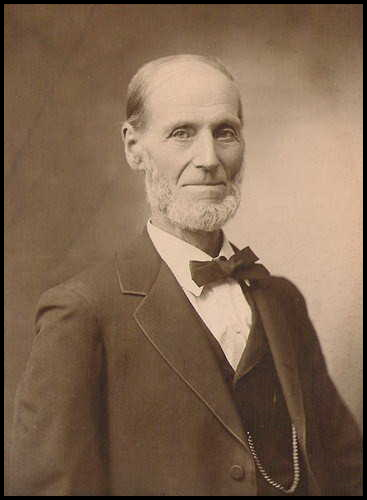

Samuel Woodburn was born to Robert and Margaret (Wasson) Woodburn on July 20, 1826 in Ballymena, Antrim, Northern Ireland. He was the oldest of their three children. His siblings were William and Margaret Woodburn. His father was a farmer. His parents, both natives of Ireland, spent their entire lives there.

Samuel was educated in Ireland’s common schools and helped his father farm until he decided to emigrate to the United States. He, accompanied by some of his friends, then spent eleven weeks crossing the Atlantic Ocean. (The year of their arrival according to Stormont’s History of Gibson County is 1847 and according to immigration records is 1849. We do know that Samuel petitioned for naturalization in Princeton, Gibson county, Indiana on October 9, 1852.) Their shipped docked in New Orleans. From there they traveled by boat up the Mississippi and Ohio rivers to Evansville, Indiana, and from there to Princeton, Indiana.

Soon after arriving in Indiana, Samuel found employment constructing the Wabash & Erie Canal. In the early 1850s the canal and reservoirs were being built in southern Indiana, but not at Princeton. Therefore, he would have lived in a canal camp near where the work was being performed.

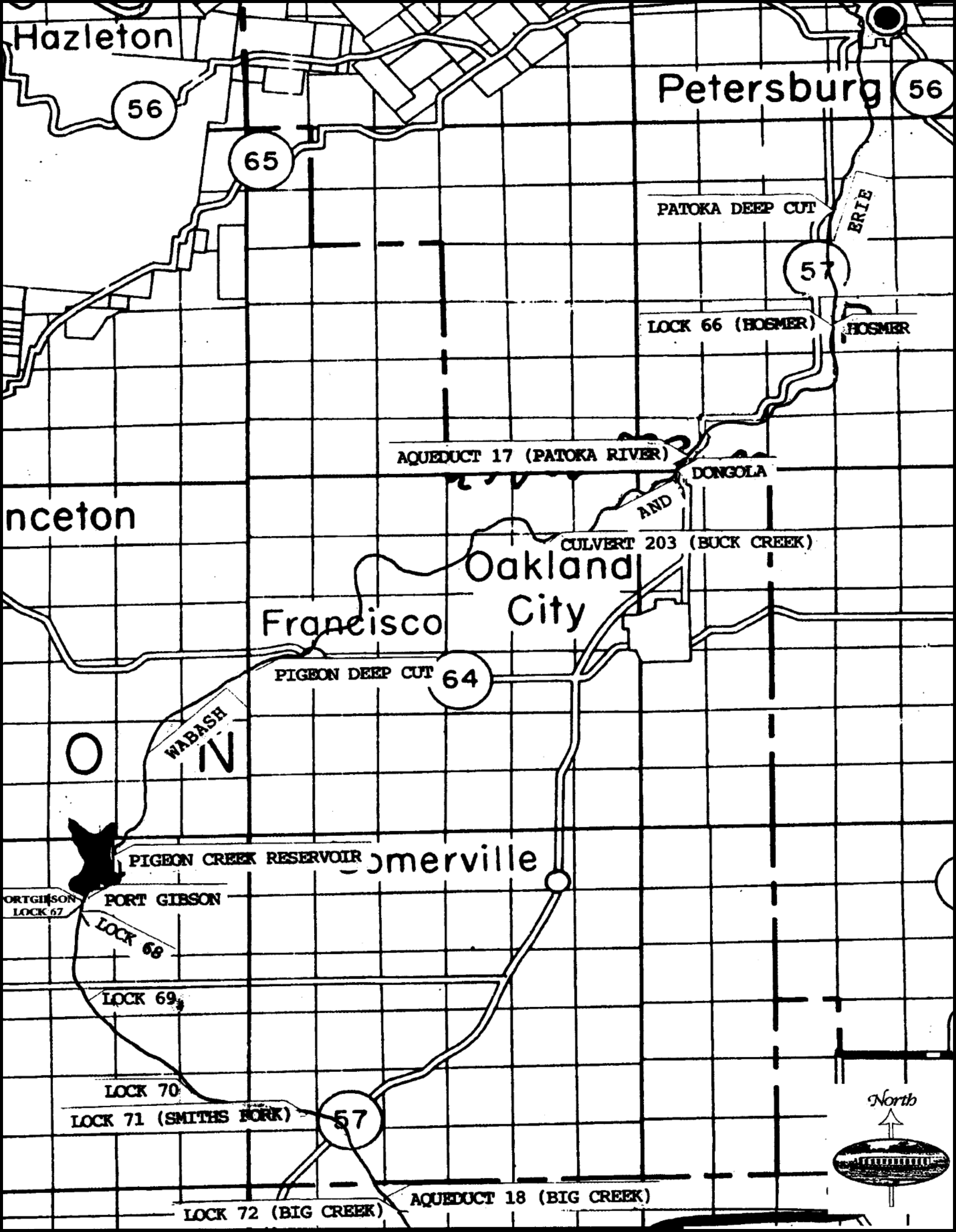

Although we do not know exactly where Samuel was working on the canal, we do know that at this time contracts were being let for work in Gibson county. The canal in the county extends 22 miles from Aqueduct No. 17 over the Patoka River at Dongola through Francisco and Port Gibson until it enters Warrick county near Big Creek. In the county the canal crosses the Pigeon Summit which is 2.8 miles long with a deep cut of 5 feet on either end to 23 feet deep at the summit. This excavation was necessary to keep the canal on a slowly descending level, as water runs downhill. This required a considerable workforce. The Pigeon Reservoir of 1,000 acres was constructed near Princeton by building a dike across the valley of Pigeon Creek. The reservoir was needed to supply additional water for the canal to Evansville. Several timber locks were required in Gibson county. Timber culverts like No. 203 at Buck Creek where the Canal Society is placing signage were also needed.

There was plenty of work to be accomplished at about $20 per month with a workforce of over 1,000. With groups of dirty, exhausted men, disease such as cholera was always a threat and at times work was delayed due to outbreaks in the summer months. This Evansville Division of the Wabash & Erie Canal was being completed by the Trust created in 1847. The first boat, “Pennsylvania,” finally reached Evansville from Lake Erie in July 29, 1853, over twenty-one years after the groundbreaking for the canal in Fort Wayne, Indiana on February 22, 1832.

Samuel later was an apprentice in the carpenter’s trade at which he became quite proficient. He worked in this trade until he joined the army.

On November 20, 1856, Samuel married Sarah Conner, the daughter of Thomas Connor, who came to American and settled in Vanderburgh county, Indiana. Sarah was born in Ireland on March 13, 1833 and arrived at New Orleans on December 21, 1844. At the time of their marriage Samuel was 30 years old and Sarah was 23. Seven children were born from this marriage: Robert, James B., William, Mary J., Frank, Henry, and Nellie.

When Indiana’s Governor called for troops for the Civil War in 1861, Samuel enlisted that fall in Company D, Fifty-eighth Regiment Indiana Volunteer Infantry, at Princeton. He was first sent to Louisville and Bardstown, Kentucky. During his enlistment he was with the Army of the Cumberland in the battles of Pittsburg Landing, Murfreesboro, Stone River, Chattanooga, Duvall’s Station, and other skirmishes. Even though he had many close calls with death during these engagements, he was not injured. After three years of service, he was discharged in July 1865.

Samuel returned to Princeton and took up his profession as a carpenter. He continued in this field until he retired.

On July 5, 1893 Samuel and his daughter left to spend time with relatives in Canada. This was reported in the Princeton Daily Clarion.

In 1896 the Daily Clarion reported that Samuel and his daughter Nellie Terry, along with Misses Hortense Mills, Agnes and Mattie Mooney, Margaret McClain, Eva and Magdalena Beck, and Mary Woodburn left via the Evansville and Terre Haute Railroad for Niagara Falls. The visit was to last about 10 days.

In October 1896 a set of three strange fires took place in Princeton. The first was about midnight on a Thursday evening when a large barn belonging to Samuel “wood burn.” The fire was not discovered until the entire barn was on fire. By the time the alarm was made and the hose wagon reached the scene, the fire was almost burned out. Samuel lost a horse, a lot of corn, hay, harnesses and other articles. The barn was insured for a small amount. It was supposed it had been deliberately set afire. The other two alarms did not result in any damage to amount to anything. They were less than an hour apart.

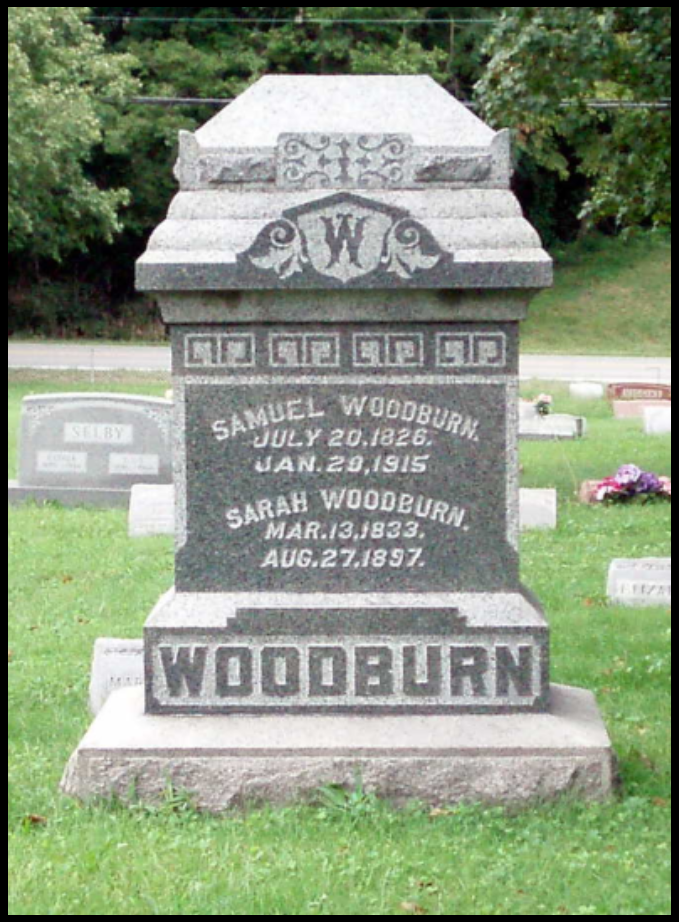

Sarah Conner Woodburn, Samuel’s wife, passed away on August 27, 1897. She was laid to rest in Princeton’s IOOF Cemetery.

Samuel was a member of the United Presbyterian church to which he liberally contributed both his time and money. He also belonged to the Grand Army of the Republic, Post No. 28, in Princeton.

Samuel was described as a 5 foot, 11 inches tall, hale gentleman with a rugged constitution, genial personality and universal good nature. He wanted what was best for his community. Through hard work he became well known and was accounted among the most worthy citizens of Gibson county.

Samuel died on January 28, 1915 in Princeton, Gibson county, Indiana and was laid to rest in Section ENE, Row 15, Lot 123 of the IOOF Cemetery. His obituary was in the Princeton newspaper as follows:

IN HIS 89TH YEAR

SAMUEL WOODBURN IS CALLED TO HIS REWARD

The End Came Thursday Night—Was One of Princeton’s Oldest Citizens

—Funeral Saturday

Samuel Woodburn, Princeton’s oldest male citizen, died Thursday night at 9:45 o’clock at his home, 704 north Main street, after a brief illness with heart ailment. Though feebler in the last few months, Mr. Woodburn had been in his usual health and up and around until two or three days ago when he suffered a serious attack. However, he was believed to be improving. Thursday he grew worse and it was realized the end was near. Mr. Woodburn was in his 89th year.

The funeral will be held at the family residence Saturday afternoon at 2:30 o’clock, conducted by Rev. Morris Watson, of the United Presbyterian church, and interment will be in Odd Fellows cemetery. The Archer Post will attend the services in a body.

JULY 20, 1826

JAN. 29, 1915

SARAH WOODBURN.

MAR. 13, 1833

AUG. 27, 1897

IOOF Cemetery, Princeton, Indiana

Photo by Jason Woodburn

Samuel Woodburn was born in County Antrim, Ireland, July 20, 1826, the son of Robert and Margaret Mason Woodburn, and there his youth was spent on his father’s farm. In 1847 he sailed for America. The vessel was eleven weeks in making the crossing. Finally landing at New Orleans, he made his way to Princeton, and was for a while employed on the construction of the [Wabash &] Erie canal through this county. Later he took up the carpenter’s trade, which he followed until his retirement from active life.

In the fall of 1861 he enlisted in Co. D. 58th Indiana regiment, and served three years, until July, 1865. He was known as one of the bravest men of his company and served in some of the heaviest engagements of the war. He was a member of Archer Post G.A.R., and was never happier than when with his old comrades recounting the stirring days of the war. His remarkably good memory enabled him to give most graphic descriptions of some of the scenes then enacted.

On November 20, 1856, he was united in marriage to Miss Sarah Conner, a native of Ireland, and to them were born seven children, all of whom survive except one son, Frank, who passed away in 1899. The wife and mother was called home August 27, 1897. Robert, James B., William, Harry, Miss Mary J. Woodburn and Mrs. F. M. Terry, all of this city and vicinity, are the surviving children.

Mr. Woodburn was one of Princeton’s most esteemed men. His cheery disposition, his friendly word for everyone, made him loved by all who knew him, and not alone in the family circle, but among the comrades and friends everywhere the lack of his kindly, cheering presence will be deeply felt.

704 N. Main & Pine Streets

Princeton, Indiana

Sources:

Ancestry.com, Public Member Trees: Connor Family, Woodburn Family

Annual Reports – 1850 -53 The Board of Trustees of the Wabash and Erie Canal

Find-A-Grave: Samuel Woodburn #138710655

Indiana Death Certificates 1899-2011

Indiana Marriage Collection, 1800-1941

Princeton City Directories: 1902, 1914

Princeton Daily Clarion: 7-6-1893, 10-8-1896, 1-30-1915

Stormont, Gil. R. History of Gibson County, Indiana: Her People, Industries and institutions. Indianapolis, IN: B. F. Bowen & Co., Inc., 1914.

U.S. Federal Census: 1860, 1870, 1880. 1900. 1910

Web: Indiana, Civil War Soldier Database Indexes, 1861-1865

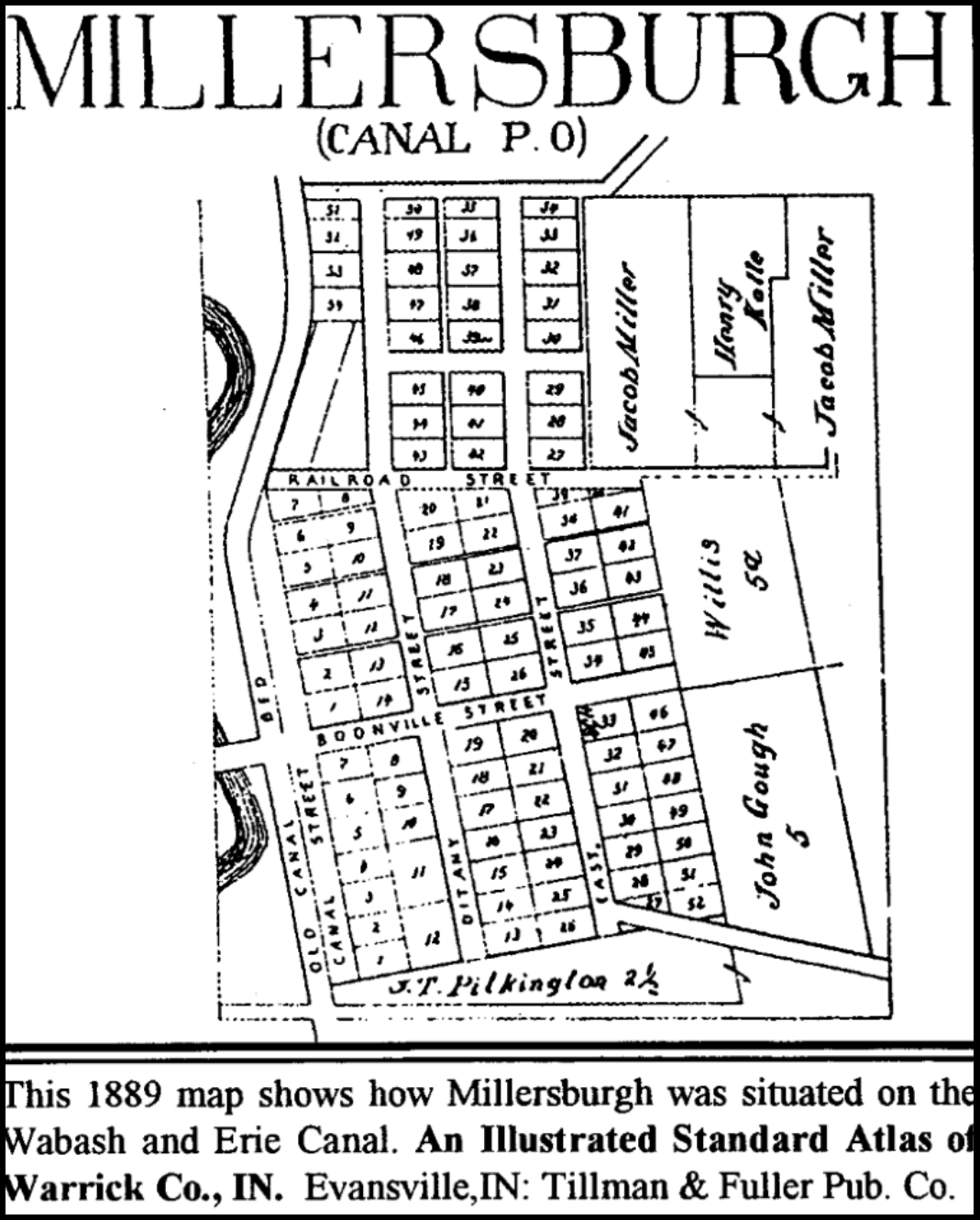

Warrick County Resident’s Canal Trip to Evansville

CSI’s 2020 spring tour will follow portions of the Wabash & Erie Canal through Warrick county. The canal passed through Millersburg, also known as Canal Post Office. Today little remains of the town except for a small cemetery. The town was abandoned and the area stripped mined for coal by Peabody Coal after Aunt Ellie lived there. Its last resident was Elmer Brown and his family, who moved further south down the canal on Towpath Road near Chandler, Indiana, in 1983.

From Evansville Courier, March 11, 1939

“AUNT ELLIE” RECALLS CANAL

Millersburg’s Oldest Resident Tells Of Her Trips To Evansville.

MILLERSBURG, Ind. March 11. – Few persons visit in Millersburg without eventually getting around to see Mrs. Ella Lockyear. Or rather, Aunt Ellie Lockyear, as she is more affectionately called by every one who has known her five minutes or longer. Aunt Ellie is the oldest resident of the town. She will celebrate her eightieth birthday on the day after the arrival or spring this year.

Seldom does a week pass without two or three persons popping in on Mrs. Lockyear and announcing they once lived in Millersburg or had relatives who at one time lived in Millersburg and asking does Mrs. Lockyear remember them. So far Mrs. Lockyear hasn’t been stumped on this remembering business.

If you once lived in Millersburg it is a cinch that Aunt Ellie knows all about you. She probably also can tell your parents’ names and where they came from before settling in Millersburg. And she’ll top off the account by relating a couple of humorous incidents that happened to your kinfolk.

Folks are a hobby of Mrs. Lockyear’s. Most of this history she keeps in the back of her head, but when events and dates temporarily escape her she has a whole box full of newspaper clippings that probably will divulge the wanted information. Mrs. Lockyear has been clipping newspaper writing about the town of Millersburg since – all the way back. She doesn’t keep these clippings in the orderly manner that a reference clerk in a city library would. They are piled helter-skelter in a big cardboard box, but Mrs. Lockyear quickly finds the clipping she wants.

Aunt Ellie Lockyear is one of three persons living within the Millersburg neighborhood who can tell of riding on canal boats. Charles Whetstone, a year younger than Mrs. Lockyear, and Thomas Pilkington are the other two.

Mrs. Lockyear took three “long” trips on canal boats. Twice she came to Evansville, on the third long trip the canal boat ride ended somewhere near Vincennes. The two trips to Evansville were made on Jack Irons’ boat. “It was a big boat,” Aunt Ellie said. “Mr. Irons used to haul flour from the three mills here into Evansville.”

“The first trip to Evansville took all day, and we started long before daylight. The second trip was even longer. There wasn’t enough water in the canal then. Ever so often, Irons would stop the mule that pulled the boat from the towpath and take time out to shift the cargo from one side to the other. The cargo was usually stored in barrels. It was quite a job to move it. Shifting the cargo made the boat list to one side and allowed it to slip thru the places where the water was shallow.”

It took two days to get to Evansville that time, but the canal boat managed to make it back in one day. The two-day trip wasn’t uncomfortable for the passengers, for the boat was entirely covered and Irons had outfitted his slow moving craft with beds and a cooking stove. Irons had experienced delays like that before. In fact, there were times when his boat was stranded for days while workmen labored to repair breaks in the earthen canal wall, which allowed all the water to escape.

Mrs. Lockyear’s third trip on a canal boat was a week-end excursion, or picnic. No cargo was carried. The canal boat picnic was sponsored by Millersburg residents. Food was brought aboard in baskets.

Mrs. Lockyear always wanted to ride on the top of the boat – to stand besides the steersman, but her parents wouldn’t permit that. They insisted she stay in the cabin and be content with just looking out the big windows.

The last craft to come down the canal, before it was abandoned, landed just above Millersburg. There was a wide place in the banks there where boats could turn around or dock without interfering with canal traffic. The canal boat never went any father. It stayed there. The stranded boat became a picnic spot for the town of Millersburg. Fishing was good where it lay. There’s no trace of the boat today. It’s stout timbers have either rotted completely away or were chopped into kindling-wood.

Mrs. Lockyear likes to tell the story how her father, C. F. McCune came to Millersburg. “He lived in Erie, Pa.,” she said. “He came all the way to Millersburg by canal boat.”

She has watched the narrow towpath, its earth packed hard by the hooves of many a patient donkey pulling an unwieldy canal boat, become obliterated and grown up in brush and trees. Mrs. Lockyear doesn’t like that. She is worried, too, about rumors that the highway department may do away with Millersburg’s last claim to distinction – the old covered bridge that spans Pigeon Creek here. [This bridge was razed in 1951.] But in the same breath Mrs. Lockyear, Millersburg’s oldest resident, admits that there must be progress.

“Even I’m, progressing,” she said with a smile. “This is the first year of my life that I’ve ever burned coal in my stove. It’s better than wood, but I still don’t like it.”

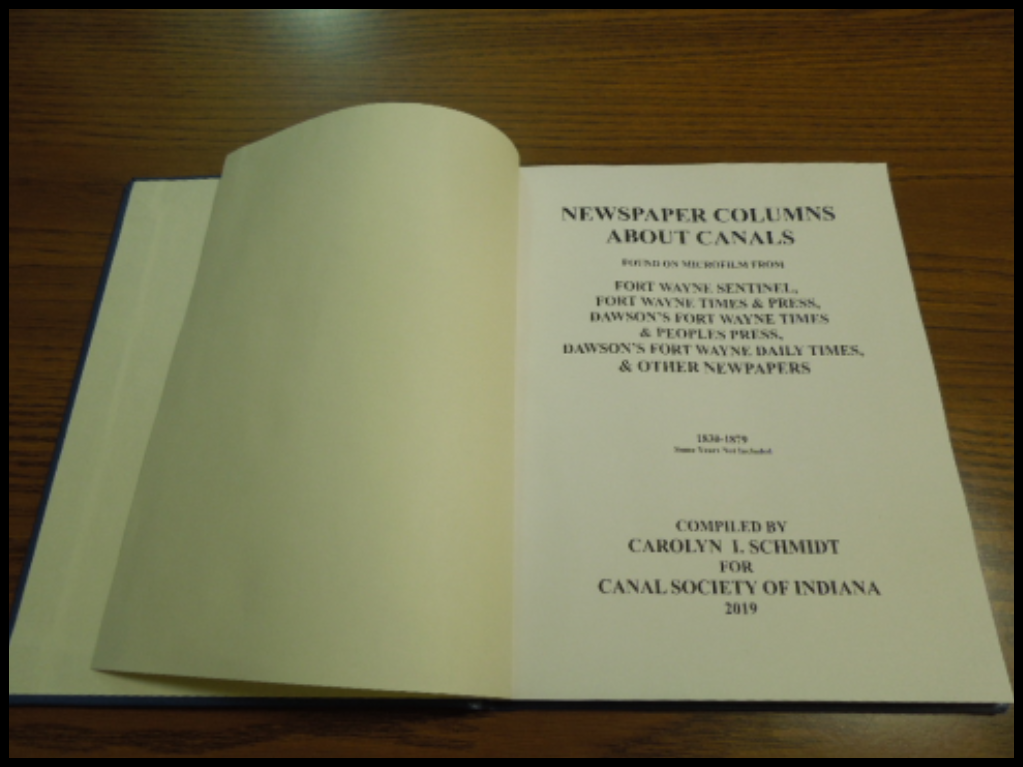

Newspaper Columns About Canals

By Carolyn Schmidt

For the past 25+ years I, Carolyn Schmidt, have been going to the Allen County Public Library and collecting newspaper articles about canals from their microfilm collection to put in “The Hoosier Packet” or “The Tumble.” This past year I have taken all of these files and combined them to be put on the CSI website. This involved changing all of them to the same format, proofreading for errors, and putting them into chronological order, all of which took several months. They were electronically sent to our Ball State student, Cate Smith, to be put on the website and are now readily available for everyone.

The Allen County Public Library’s genealogy department has a program for collecting family genealogies, which involves submitting two printed copies of a family’s genealogy. The library sends both copies to the bindery. After the copies are bound, one copy stays at the library and the other it sent to the family free of charge.

The Allen County Public Library’s genealogy department has a program for collecting family genealogies, which involves submitting two printed copies of a family’s genealogy. The library sends both copies to the bindery. After the copies are bound, one copy stays at the library and the other it sent to the family free of charge.

Knowing about this program and knowing that all the CSI “Hoosier Packets” and “The Tumble” have been bound and put on the library’s shelves, I asked, “If I supplied two copies of these newspaper columns, would you bind them and give us a copy free of charge?” I submitted this book in late September and received the bound copy in mid-December. We greatly appreciate having a bound copy for our archives and knowing that the other copy is available to all library patrons in the genealogy section of the library. Hip hip hooray for the library!

Indiana’s Canal Commissioners

By Bob Schmidt

Having failed at several attempts to build a canal at Jeffersonville around the falls on the Ohio River, Indiana turned its attention toward the north. The portage at Fort Wayne between the Maumee and Wabash watersheds had frequently been mentioned as a potential canal site. Some preliminary engineering work had already been done. Canal proponents appealed to Washington City for help. On May 26, 1824, Congress responded with a right-of-way of 90 foot on each side of the canal route or 180 feet total through federal lands between the Maumee and Wabash rivers. The Indiana legislature rejected this offer for lack of gifted land to sell for funding such a canal construction and because the granted territory was through Indian lands.

Indiana’s second attempt to receive Federal support for canal building was successful in the final legislative days of March 1827. On March 2 an act was passed that provided for the transfer of some 527,271 acres of Federal lands to the State of Indiana for the specific purpose of building a canal from the Auglaize River at Defiance, Ohio to the Tippecanoe River in Indiana. Alternate sections on either side of the canal route that were selected by the state were to be sold to raise funds to build this canal. Also stipulated was that work was to commence within 5 years and be completed in 20 years, with no tolls for any use by the federal government. On January 5, 1828 the Indiana legislature accepted this grant. A few days later on January 14, the legislature established a three-man-board of Canal Commissioners for two-year-terms to plan and administer the proposed canal that was to become the Wabash & Erie Canal. Governor James B. Ray, still a proponent of rail roads, estimated the land value at about $1,250,000 and thought the grant sufficient to build such a canal. That same year, on July 4, groundbreaking occurred for both the C&O Canal and the B&O railroad in Maryland. Ohio also had two canal construction projects underway since 1826. Indiana chose to build the canal, which came with the federal land funding.

The Legislature carefully selected three men to be the initial members – Samuel Hanna, David Burr and Robert John. They were to receive a wage of $2 per day out of a 2-year-allotment of $2,000 to be taken from the 3% federal land sales fund. An additional amount of $500 was to be drawn for surveying instruments and equipment. The legislature carefully chose men from various parts of the state to represent the areas in which there was interest in building canals. Their charge was to select the route of the canal, identify the sections to be assigned to the state from the federal grant, and hire the necessary engineers.

Samuel Hanna came to Fort Wayne as a trader with the Indians in 1819, the year the fort was officially closed. The Indian Agency was still active until 1826 when Agent John Tipton abruptly moved it to Logansport. When Allen County was formed in 1823, Hanna became Postmaster and subsequently Associate Judge of the Circuit Court. Hanna also served various terms in the Indiana House and Senate from 1824–1834. He was concerned that lack of transportation in the swampy area around the town would hamper its development. He was very pro canal. After his appointment as Canal Commissioner, he discovered that they lacked the necessary surveying tools to develop a route for feeding the summit level of the proposed canal. Since $500 was designated just for equipment, he used his personal funds to go to New York. There he obtained the necessary tools. In the summer of 1829 he and his fellow commissioner, David Burr, laid out the proposed route of the Feeder Canal 6½ miles north of Fort Wayne on the St. Joseph River. 1829 was a year of controversy among the various factions in the Legislature deciding whether or not to proceed with a Maumee/Wabash canal. In October 1829 Indiana agreed with Ohio to turn over the portion of the 1827 land grant that lay in Ohio to that state in turn for their agreement to build the Ohio portion of the Wabash & Erie Canal.

David Burr, originally from Jackson County, was not a politician but was at the time Postmaster in nearby Salem, Washington County. He became the President of the Board of Commissioners. He also was pro canal and was selected to support canal activity in the central part of the state. He and Robert John met together in Indianapolis in July 1828 and reviewed the canal situation. They concluded that Indiana lacked the surveying tools to lay out a canal route. Hanna agreed to go east for equipment. After working with Samuel Hanna, Burr became interested in the upper Wabash area. In 1830 he purchased land near the Paradise Spring treaty grounds and later became Postmaster of a small settlement called Treaty Ground. That same year a Land Office was opened to begin selling the canal lands. In 1834 he and Hugh Hanna, Samuel’s brother, laid out the town of Wabash and made it the county seat. Burr also operated as trader and ran a hotel in Wabash. At the time of the 1835 Irish Riot between Lagro and Wabash, Burr was there to take action, call militia and arrest the leaders of the riot.

Robert John was from Brookville in Franklin County. He represented the interest of the Whitewater valley. He was a County sheriff, editor of the Inquirer, and host of the Brookville Hotel. As a canal on the Whitewater was out of the question at this point, he probably felt out of touch and resigned in May 1829. His replacement was Jordan Vigus, Corydon tailor and banker (1817), Indianapolis tavern keeper (1826) and a close ally of John Tipton. Persuaded by his relationship with Tipton he moved to Logansport in 1829 and became its first Mayor in 1830.

The Board of Commissioners was reorganized in January 1830 with 3-year-terms for the commissioners. David Burr as President and Jordan Vigus were again selected. The new member was Samuel Lewis of Fort Wayne, who replaced Samuel Hanna. The pro canal faction in Indiana had now prevailed so that in the summer of 1830 Joseph Ridgeway, an Ohio canal Engineer, was hired by the Commissioners to complete the 32 (6+26) miles to the mouth of the Little River in Huntington. His report appears in The Hoosier Packet May 2013. Only Jordan Vigus was at the groundbreaking in Fort Wayne on February 22, 1832. In June 1832 the board hired Jesse Lynch Williams, also an Ohio Engineer, to be the Chief Engineer. This board carried on all of the administrative functions until January 1836 when again it was reorganized and expanded to nine members as a result of the increased demands of the 1836 Mammoth Internal Improvements Bill signed by Governor Noah Noble.

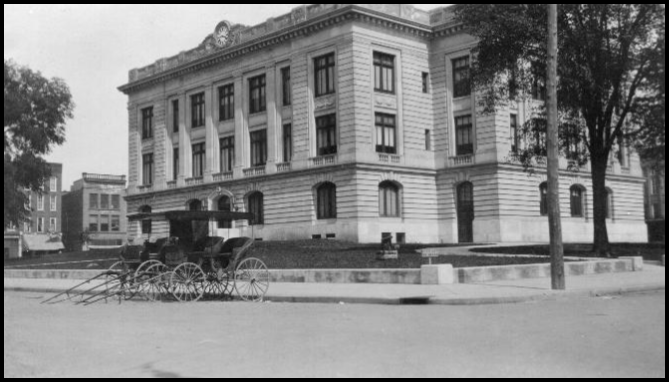

Courtesy of the Indiana Digital Archives

Samuel Lewis, born in Virginia, moved with his family first to Cincinnati and then to Brookville, Indiana in 1817. There he courted Catherine Wallace, the sister of future Governor David Wallace. They were married in Brookville in December 1818. Samuel became a businessman and was elected to the Indiana House in 1826. In 1827 he was nominated by President John Quincy Adams to be the Indian sub-agent at Fort Wayne’s Indian Agency, which had opened in 1824. In 1828 the Canal Land Office was moved to Logansport by John Tipton placing both

the Indian Agency and the Canal Land Office in Logansport.. In October 1832, Samuel became the receiver of monies at the Canal Land Office. In January 1834 he became a member of the Board of Directors of the Fort Wayne Branch of the Indiana State Bank. He was an active canal commissioner and traveled to Buffalo, New York to recruit canal workers. His brother-in-law, David Wallace, went on to serve in the Indiana legislature. David became Lt. Governor under Noah Noble and then Indiana’s Governor from 1837-1840. Samuel Lewis continued to serve as Canal Commissioner through all the board reorganizations until Feb 1840 when the final three-man-board was replaced by a 1-man-board – ex Governor Noah Noble of Franklin County. In July 1847, Indiana’s Wabash & Erie Canal was turned over to a private Trust that had three trustees – Charles Butler, a New York lawyer; Jesse Lynch Williams, the Chief Engineer; and Thomas Blake, a Terre Haute businessman.

John Scott, Judge from Wayne County replaced Jordan Vigus, who had completed his 3-year-term in 1833. Scott served only 1 year and was replaced by James B. Johnson of Tippecanoe County in 1834. Johnson, a businessman, completed his term in 1836 when the nine-man-board was established.

The new nine-man-board will be covered in a future issue of The Tumble.

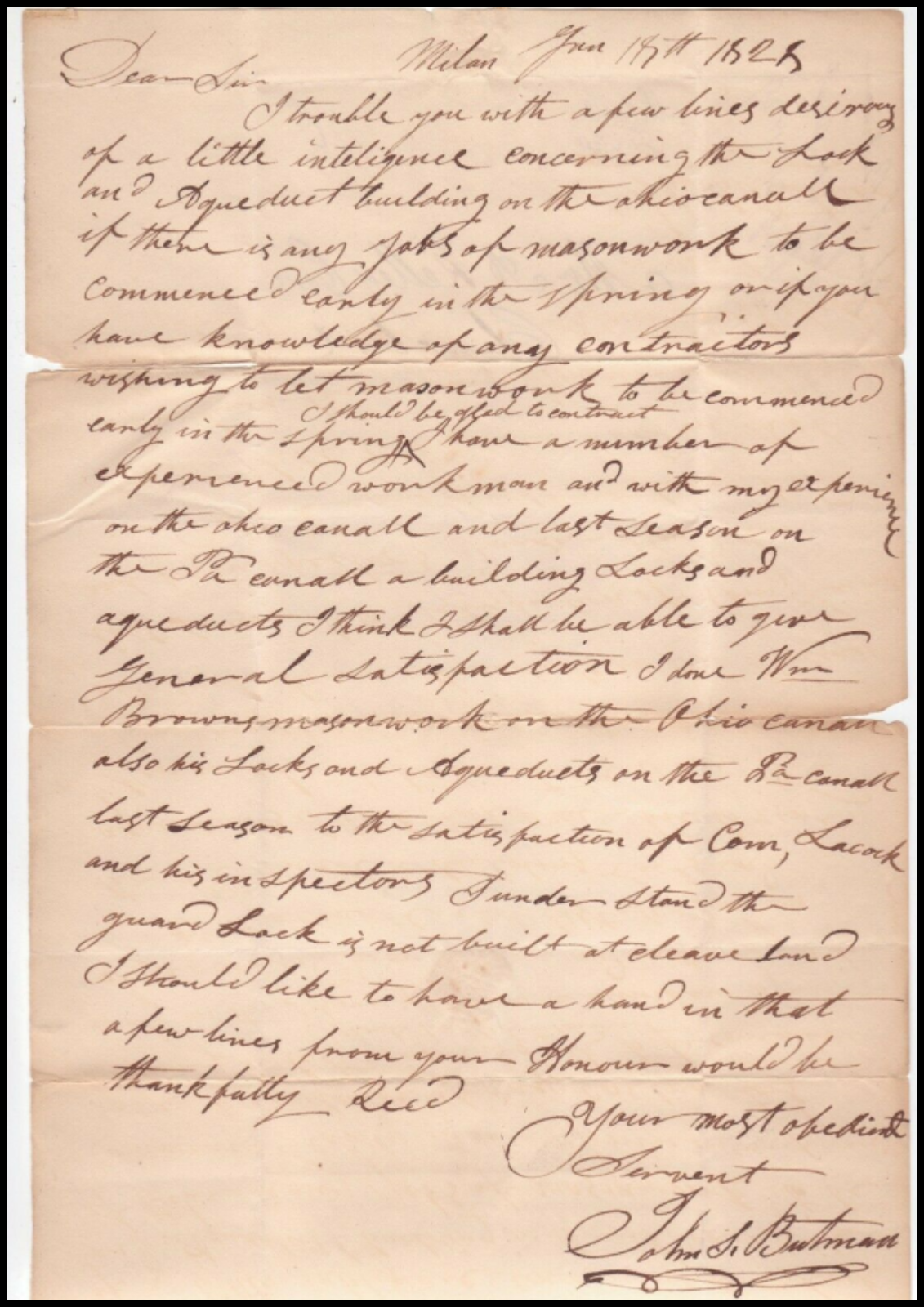

John Butman Seeks Work on Ohio Canal

Neil Sowards, CSI member from Fort Wayne, Indiana recently found the following letter on E-bay. It is an interesting stampless folded letter, with a Milan, Ohio manuscript cancellation and manuscript “10” marking that was written by John S. Butman, on January 18, 1829 and was mailed on January 20, 1829 to Mr. Alfred Kelly, Ohio Canal Commissioner in Cleveland, Ohio.

Neil Sowards, CSI member from Fort Wayne, Indiana recently found the following letter on E-bay. It is an interesting stampless folded letter, with a Milan, Ohio manuscript cancellation and manuscript “10” marking that was written by John S. Butman, on January 18, 1829 and was mailed on January 20, 1829 to Mr. Alfred Kelly, Ohio Canal Commissioner in Cleveland, Ohio.

In the letter Mr. Butman writes, “I trouble you with a few lines desiring of a little intelligence concerning the lock and aqueduct building on the Ohio Canal if there is any jobs of mason work to be commenced early in the spring or if you have knowledge of any contractors wishing to let mason work to be commenced early in the spring, I should be glad to contract. I have a number of experienced workmen and with my experience on the Ohio Canal and last season on the PA canal on building locks and aqueducts, I think I will be able to give you general satisfaction. I done William Browns mason work on the Ohio Canal, also his Locks and Aqueducts on the Pa Canal last season to the satisfaction of Com. Lacock and his inspectors. I understand the guard lock is not built at Cleveland. I would like to have a hand in that – a few lines from your Honor would be thankfully rec’d. – Your most obedient Servant – John S. Butman.”

A Passenger Canal Boat

A description of the canal boat Marguerite II published by the Delphos Canal Commission of Delphos, Ohio, related what was found on many canal boats. Portions of it have been changed to apply to canal boats in Indiana.

Canal boats had a cabin for its captain. Since the typical canal boat was a floating business, it’s Captain’s cabin was not only a home, but a warehouse, galley, office and more. Very often the Captain was its owner or it was owned by a close relative. Often his whole family lived on board. Everything needed for the family and the business was stored or available there. The cabin in which they lived from March through November was intended to be both comfortable and efficient, as well as a safe haven from the elements and the other people on board the boat.

Feeder Canal Marked in Fort Wayne

The 6½-mile-long St. Joseph Feeder Canal, which fed water that was backed up by a dam on the St. Joseph River into the Wabash & Erie Canal at its summit in downtown Ft. Wayne, Indiana, has been marked near the soccer fields/Sports Plex of Purdue University Ft. Wayne. The CSI funded sign was erected by Tad Smith, Director of Grounds Operations for Purdue, on January 15, 2020. CSI director and Allen County Historian, Tom Castaldi, delivered the marker and worked with Tad and Gregory Justice, Associate Vice Chancellor of Facilities Management for Purdue to select the site for it. CSI thanks them for helping with this project.

Gardner B. Herrington: Canal Pioneer in Carroll County

By Mark A. Smith

At the onset of this writing I wish to grant credit to VFW Honor Guard Member Frank Wolf and ultimately his great-uncle George Wolf; Frank for the donation of this resource and George for retaining instead of discarding it.

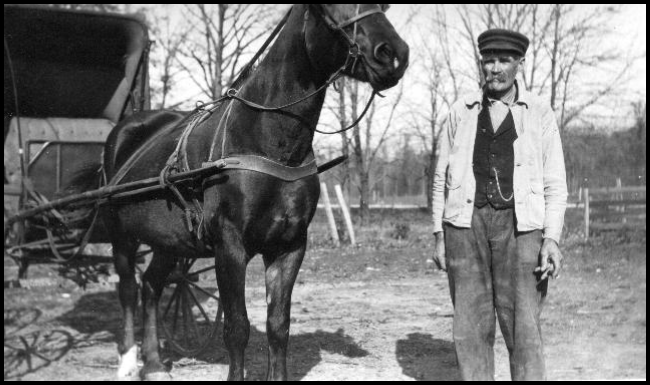

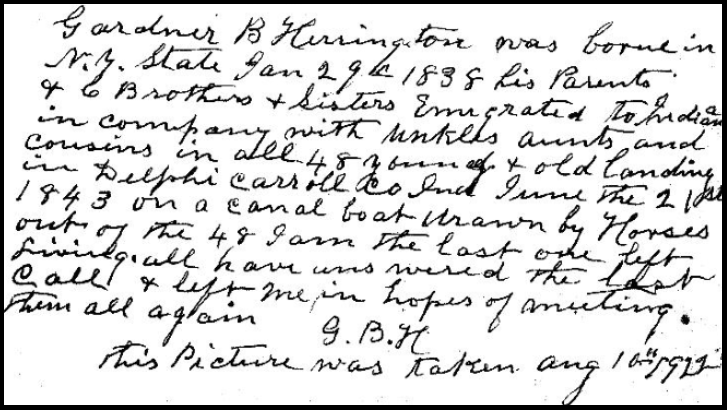

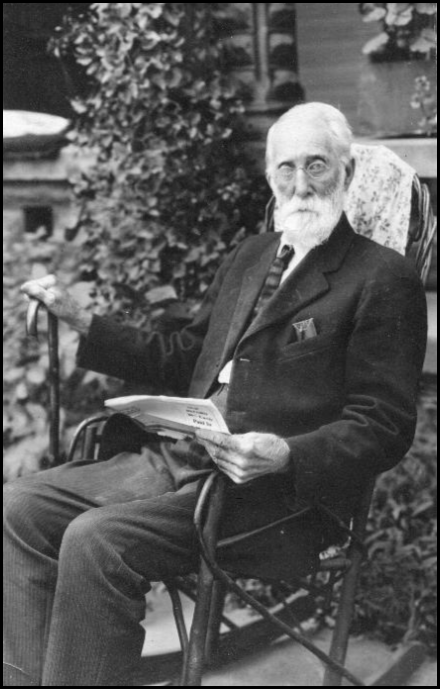

Frank took several photographs to the Carroll County Veteran’s Office and asked that they be sent to me, Mark Allen Smith, since I am the County Historian for Carroll county. One of the pictures was of Mr. Herrington. He had hand written the following inscription on its back.

“Gardner B. Herrington was borne in N.Y. State Jan 29th 1838 his Parents and 6 brothers and sisters emigrated to Indiana in company with unkels [uncles] aunts and cousins in all 48 young and old landing in Delphi Carroll Co Ind June the 21st 1843 on a canal boat drawn by Horses out of the 48 I am the last one left living all have answered the last call & left me in hopes of meeting them all again. GBH. This picture was taken Aug 10th 1922.”

“Gardner B. Herrington was borne in N.Y. State Jan 29th 1838 his Parents and 6 brothers and sisters emigrated to Indiana in company with unkels [uncles] aunts and cousins in all 48 young and old landing in Delphi Carroll Co Ind June the 21st 1843 on a canal boat drawn by Horses out of the 48 I am the last one left living all have answered the last call & left me in hopes of meeting them all again. GBH. This picture was taken Aug 10th 1922.”

It appears that all 48 members of his family arrived on the same canal boat.

Bob Schmidt, president of the Canal Society of Indiana, informed me that the first boat through from Lafayette, Indiana to Toledo, Ohio was the Albert S. White on May 8, 1843. The Grand Celebration for the opening of the Wabash & Erie Canal between these two points occurred on July 4, 1843. The Herrington’s arrival date between these two occasions implies that they were true pioneers in that sense.

Further research shows that the name Herrington is often spelled Harrington in old records. Gardner B. Herrington was born in either Seneca County, New York (Lafayette Journal and Courier) or Steuben County (Flora Hoosier Democrat). I believe he was born in Seneca county.

According to the 1850 and 1860 U.S. Federal Censuses Gardner was in Carroll county in 1850 at age twelve, and in 1860 at age twenty-two his residence was in Tippecanoe county, Indiana in the Battleground area. His marriage was to Nannie E. Haire (1846-1901) on May 4, 1870 in Carroll county. Nannie was probably her nickname since in some censuses she is listed as Sarah E., which is probably her given name.

Further residences or lot ownerships for our canal pioneer included the Lafayette area where he was shown to reside “west of canal opposite change bridge” according to the Lafayette City Directory of 1885 and was a farmer at that time. The change bridge allowed the horses or mules that pulled the boat to cross to the opposite side of the Wabash & Erie Canal and continue on their journey.

In the 1890s he maintained residence and ownership of property by a vacant lot on Indiana Street, which was sold to a John Kashner in May of 1893. In 1891 he moved to Clymers.

In 1910 the census shows Gardner, age seventy-one, residing at Culver, Marshall county, Indiana. In 1920 he was listed in Lafayette, Tippecanoe county, Indiana residing on Main 1st Street (probably an intersection).

His daughter was Maggie Herrington. She was married to Silas Yundt at the home of her parents two miles southwest of Logansport by Rev. Hutchens of Camden.

His mother was Mrs. Drusilla Herrington whose passing occurred September 22, 1890, her funeral being in the home of her son, officiated by the Rev. VanCleave, with her burial in the Masonic Cemetery.

Gardner’s wife, Nannie E., who was born on March 11, 1846, passed away on January 6, 1901. Her parents were James and Drusilla Hair [Haire]. She was listed as a member of the Methodist Church at Clymers. Two sisters and one brother as well as Gardner survived her.

Other family members included Sarah Herrington, who was married to Joseph C. Knight according to the September 2, 1853 Times, and Gardner’s sister Jennie, who was born in Oswego, New York on December 26, 1836, and passed away at Gardner’s home near Delphi on Thursday, May 15, 1890 where her funeral was later held with Reverend VanCleve officiating. She was buried at the Masonic Cemetery in Delphi.

Gardner B. Harrington passed away on November 19, 1925. His passing was noted in the November 21, 1925 Lafayette Journal and Courier. He died at Kokomo, Indiana in the home of his great-nephew William according to the Flora Hoosier Democrat and was buried at Clymers. His death certificate shows he died of infirmities of age. He fell off of a sofa and fractured his hip, suffered for 2 weeks and passed away. He was 87 years, 10 months and 21 days old. Although he died on November 19, he was not buried until November 22, 1925 at the Clymers Cemetery, in Clymers, Cass county, Indiana.

Gardner B. Harrington passed away on November 19, 1925. His passing was noted in the November 21, 1925 Lafayette Journal and Courier. He died at Kokomo, Indiana in the home of his great-nephew William according to the Flora Hoosier Democrat and was buried at Clymers. His death certificate shows he died of infirmities of age. He fell off of a sofa and fractured his hip, suffered for 2 weeks and passed away. He was 87 years, 10 months and 21 days old. Although he died on November 19, he was not buried until November 22, 1925 at the Clymers Cemetery, in Clymers, Cass county, Indiana.

Our subject seems to have had a full and varied life with many residences and many experiences, which are characteristic of a true pioneer of the Canal Era.

Other photos or Gardner and the courthouse in Delphi, Indiana were also sent to me. They are as follows:

Old Canal House on the Summit Then and Now

By Tom Castaldi