Index:

Thomas Armstrong Morris

Find-A-Grave # 8537742

By Carolyn Schmidt

Thomas Armstrong Morris was born in Nicholas county, Kentucky on December 26, 1811 to Morris and Rachel (Morris) Morris. His great-grandfather, James Morris, Sr., and his maternal great grandfather, John Morris, were brothers, who came from Wales along with another brother in the early settlement of Virginia. James Morris lived in Pennsylvania and was an ensign in Col. John Philip De Haas’s regiment, 1st Pennsylvania battalion, having been appointed by Gen. Gates on November 3, 1776. This battalion participated in the operations in Canada under Benedict Arnold and also Ticonderoga in 1776.

Thomas Armstrong Morris was born in Nicholas county, Kentucky on December 26, 1811 to Morris and Rachel (Morris) Morris. His great-grandfather, James Morris, Sr., and his maternal great grandfather, John Morris, were brothers, who came from Wales along with another brother in the early settlement of Virginia. James Morris lived in Pennsylvania and was an ensign in Col. John Philip De Haas’s regiment, 1st Pennsylvania battalion, having been appointed by Gen. Gates on November 3, 1776. This battalion participated in the operations in Canada under Benedict Arnold and also Ticonderoga in 1776.

He was the third son born to Morris Morris (1780-1864) and Rachel Morris (1786-1863). Their children were William Little Morris ( ?-1864), Austin W. Morris (1804-1851), Thomas Armstrong Morris (1811-1904), John David Morris (1815-1895), Amanda Melvina Morris Mothershead (1817-1851, Julia Ann Morris Ross (1820-1895), and Elizabeth Mitchell Morris Defrees (1824-1904).

When Thomas was ten years of age his parents moved from Kentucky to Indianapolis, Indiana by covered wagon. He later described early Indianapolis saying that life there “was like camping out in a forest on a hunting expedition, except that the camping places were cabins instead of tents or brush houses.” He was baptized in the White River by Henry Ward Beecher. In 1823, he began to learn the printer’s trade. At the end of three years he was sent to a private school taught by Ebenezer Sharpe. After 4 years, at age 19, he was appointed as a cadet to West Point. When he was graduated in 1834 he was fourth in a class of thirty-six and was brevetted as second lieutenant of the 1st artillery in the regular army.

After about one year’s service at Fort Monroe, Virginia., and Fort King, Florida, he was sent by the war department to assist Maj. Ogden, of the engineer corps, in constructing the National Road in Indiana and Illinois, and had charge of the division between Richmond and Indianapolis, Indiana. This was the first turnpike road in Indiana.

Central Canal Project

In 1835 Thomas resigned from the U.S. service to work as Indiana’s resident engineer. In February of that year a survey to locate the line of the Central Canal had been authorized by the Indiana general assembly to be supervised by state canal engineer Jesse Lynch Williams. The canal was to begin at the Wabash and Erie Canal at the mouth of the Mississinewa River and end at the Ohio River at Evansville. This survey was followed by a second survey by Thomas to determine the width, depth and other canal definitions. He was then given the job of superintending its construction.

Thomas A. Morris reports, “I located the line of this canal, laid if off and superintended the construction. I surveyed the line from Wabashtown [Wabash] to Martinsville. It went through a rather rough country. I camped out for six months, but came into town for Christmas. Many a morning we had to shake the snow off ourselves when we got up.

“There were forests and thickets and a great deal of swampy ground. There was a big swamp a mile or so south of Broad Ripple, which contained water nearly all the year and was a great feeding place for wild ducks. There was another big swamp southeast of this, near Hiram Bacon’s place on the Noblesville road, west to the [White] river. Remains of the former swamp still exist. I have had some good sport shooting snipes and ducks there.”

Construction of the Central Canal began in 1836. The first portion of the Indianapolis and Northern divisions of the canal were constructed by contractor John Burke and about 750 workers who cleared the canal route of trees and stumps by using shovels and picks to excavate a 6 feet deep and 60 feet wide canal route. They also built a feeder dam on the White River with an inlet to the canal. By the fall of 1838 the Central Canal was completed from Broad Ripple through Indianapolis to Pleasant Run. It was watered and was used to bring lumber and farm products from Broad Ripple to Indianapolis. Soon sawmills, and woolen, cotton, and paper mills were erected along its banks to utilize its water power.

Gen. Thomas Armstrong Morris was married, in 1840, to Elizabeth Rachel, daughter of John Irwin, of Madison, Indiana. They had five children: John I. Morris (1846-?), Thomas O’Neil Morris, (1846-?) a division engineer on the Big Four; Elnora Irwin (Morris) Chambers, (1852-?), the widow of Dr. John Chambers, and Milton A. Morris, (1854-?), the secretary of the Indianapolis Water Company.

Service With The Railroads

In 1841 Thomas took over as chief engineer of the Madison and Indianapolis railroad after it had been abandoned by the state at Vernon, Indiana. It was the first railroad in the state. Through his extreme efforts it was completed by 1847 after he conceived a stock-swapping plan to finance it. The plan gave area farmers railroad stock in exchange for land and labor. His success led him to further railroad endeavors.

From 1847 to 1852 he was chief engineer of the Terre Haute and Richmond railroad, connecting Terre Haute and Indianapolis, and in 1880 it became part of the “Vandalia.” During the same time he was chief engineer of the Indianapolis and Bellefontaine railroad, later part of the “Big Four.” From 1852 to 1854 he was chief engineer of the Indianapolis and Cincinnati railroad and from 1854 to 1857 was president of the same. He drew the plans and superintended the construction of Indianapolis’ Union Depot completed in 1853, the first of its kind in this country. Later, after remodeling, it was called Union Station. At his time he was also a colonel in the Indiana militia. From 1857 to 1859 he was president of the Indianapolis and Bellefontaine road, and from 1859 to 1861 chief engineer of the Indianapolis and Cincinnati railroad.

In October 1850 a Constitutional Convention was called to revise Indiana’s governing document. There were a total of 150 delegates at this convention. Debate continued until February 10, 1851. One of the results was the provision to prevent the state from borrowing for capital improvement projects since the earlier projects had driven the state to the verge of bankruptcy. During the debates in Indianapolis an important event occurred at the door of the State Capital — the selling of the Central Canal. The canal Thomas had built was put out of business by the railroads just like the rest of Indiana’s canals.

In January 1850 the legislature had authorized the sale of the Central Canal. The auction occurred on November 16, 1850. George Shoup, James Rariden, and John Newman, who were all members of the constitutional convention either left the meeting or it was recessed for a while, for they bid and bought the canal for $2,425. On February 7, 1851 they transferred it to Francis Asbury Conwell, Shoup’s brother-in-law, and some other investors. What the relationships and deals were we don’t know. The title of the group was the Central Canal Manufacturing, Hydraulic and Water Works Company.

Three Month Civil War Service

When the war broke out in 1861 Thomas was appointed Quartermaster General of the state by Gov. Oliver P. Morton. He had charge of the equipment of Indiana’s first regiments at Camp Morton. They promptly entered the field. As General he commanded the first brigade of troops that went from the state. That April he became a brigadier general. Later that spring he commanded the brigade that became known as the “Indiana Brigade.” This brigade was ordered to Western Virginia as part of the Department of the Ohio.

When the war broke out in 1861 Thomas was appointed Quartermaster General of the state by Gov. Oliver P. Morton. He had charge of the equipment of Indiana’s first regiments at Camp Morton. They promptly entered the field. As General he commanded the first brigade of troops that went from the state. That April he became a brigadier general. Later that spring he commanded the brigade that became known as the “Indiana Brigade.” This brigade was ordered to Western Virginia as part of the Department of the Ohio.

He was in the West Virginia campaign, and commanded at the battle of Phillippi, June 2, 1861, which was the first engagement of the Civil War. They took part in the battle of Rich Mountain June 11. On July 6, Union Major General George McClellan ordered Thomas to move 4,000 men from Philippi to within a mile of the Confederates. Camp at Laurel Hill. He skirmished with 3,500 of Brigadier Gen. Robert S. Garnett’s Confederates while McClellan led 2 brigades of about 7,000 men against 13,000 men who were holding Rich Mountain pass. On July 7 the Laurel Hill skirmish began. On July 9 the Union forces captured Girard Hill, where they set up artillery. The artillery began firing about noon on July 10 and continued the next day. When Garnett learned on July 11 that Rich Mountain had been taken, he retreated around mid-night. Union forces seized the abandoned Laurel Hill on July 12. On July 13 Thomas’ brigade attacked the retreating Confederate forces led by Garnett along the Cheat River at Carrick’s ford. Here Garnett was killed and, with reinforcements from the 7th Indiana regiment, the Confederates were defeated. This guaranteed the Virginia Unionist’s control of West Virginia and allowed it to secede from Virginia. His campaign was with the three months’ troops and he was mustered out of service on July 27, 1861. He had won all his battles, but General George McClellan was credited with Thomas’ achievements

In September 1862 Thomas was offered the position of Brigadier General of the volunteer army. But due to an over supply of Governor appointed generals and McClellan blocking his appointment, it was held up for fourteen months. He was offered the position of Major General of the volunteer army. He did not accept either offer. He returned home to civilian pursuits.

Back To The Railroads

From 1862 to 1866 Thomas was the chief engineer of the Indianapolis and Cincinnati railroad, and during that time built the road from Lawrenceburg to Cincinnati. From 1866 to 1869 he was president and chief engineer of the Indianapolis and St. Louis railroad, building the road from Terre Haute to Indianapolis. From 1869 to 1872 he was the receiver of the Indianapolis, Cincinnati and Lafayette railroad.

From 1862 to 1866 Thomas was the chief engineer of the Indianapolis and Cincinnati railroad, and during that time built the road from Lawrenceburg to Cincinnati. From 1866 to 1869 he was president and chief engineer of the Indianapolis and St. Louis railroad, building the road from Terre Haute to Indianapolis. From 1869 to 1872 he was the receiver of the Indianapolis, Cincinnati and Lafayette railroad.

Meanwhile the Central Canal passed through several hands and at one time was owned by a company from Rochester, New York. Various proposals were offered to supply the city of Indianapolis with the canal waters without success. On October 7, 1869 the Water Works Company of Indianapolis was formed to provide canal water for transportation, mills and a water turbine to pump well water for city use. Title for the Central Canal was transferred from the Rochester, New York firm to the new Water Works Company of Indianapolis (WWCI).

The new company used the canal water to operate pumps for well water at the Washington Street station and to supply the city with canal water for fire protection. However, local residents were not required to switch from their individual wells to the city system.

In 1877 Thomas was appointed one of the commissioners to select plans and superintend the construction of a new state house to replace the one that his father had helped build nearly fifty years earlier. It was completed in 1888.

By 1880 the WWCI had spent $1.5 million in equipment and piping but still only served about 1,400 of the 15,000 potential households. Indianapolis population had grown from 45,000 in 1870 to about 75,000 in 1880. The company was in receivership and was sold to a newly formed Indianapolis Water Company (IWW) at a Sheriff’s auction on April 21, 1881.

In 1881, upon the resignation of T. Edward Hambleton, Thomas became the second president of the Indianapolis Water Company and inherited all the mistakes that had been made. The company used the Central Canal to carry water from the White River to the pumping station and then send it to Indianapolis homes and businesses. Thomas soon had a new board of directors and things began to get better. The customer base was soon greatly expanded. By 1881 it served 2,800 homes, by 1898 8,000, and by 1904 14,296. Pumping facilities were being expanded.

Thomas Armstrong Morris remained as President until his death in 1904. Despite his death the Indianapolis Water Company continued to grow and by 1905 a water treatment facility was added to utilize canal water for drinking. IWC also encouraged the recreational use of the Central Canal. Fairview, Armstrong and Riverside Parks were established along the banks of the old canal. IWC had its own steamboats, the Diane and the Cleopatra, which offered rides on the canal.

In 1912 IWC and the Central Canal was sold to a private investor, Clarence H. Geist, whose family retained ownership for the next 40 years. The Geist Reservoir was constructed on Fall Creek in 1943 to supply the city with another consistent water source.

In 1952 the Indianapolis Water Company was purchased by the sons of Clint Murchison, a millionaire from East Texas. They sold their interest in the company in 1965. The Central Canal still operates today carrying water from the White River to the filtration plant and provides some of Indianapolis’ residents with water.

From his early life Thomas was never very long out of active employment. He amassed a large and valuable estate. In his later years he worked to support public interests such as being a life trustee of the Consumers’ Gas Trust Company.

General Thomas Armstrong Morris died on March 22, 1904 in Indianapolis, Indiana at the age of 92. He was buried in Section 6, Lot 1, Crown Hill Cemetery, Indianapolis, Marion County, Indiana, a cemetery for which he was an incorporator. His meager grave stone does not reflect the importance of this man in Indiana’s history.

Sources:

A Biographical History of Eminent and Self-made Men of the State of Indiana. Cincinnati, OH? Western Biographical Publishing Company, 1880.

Ancestry.com

http://trees.ancestry.com/tree/316961/person/6006823961/medizax/2?pgnu Thomas Armstrong Morris General

Find-A-Grave Index 1800-2012, memorial #8537742

Bakken, J. Darrell. Now That Time Has Had Its Say: A History of the Indianapolis Central Canal, 1835-2002. Bloomington, IN/ 2003.

Giffin, Marjie Gates. Water Runs Downhill: A History of the Indianapolis Water Company and Other Centenarians. Indianapolis, IN/ Privately Printed, 1981.

McGrath, Hugh J. and Stoddard, William. Men of Progress. Indiana. Indianapolis, IN/ The Indianapolis Sentinel Company, 1899.

Tucker, Spencer C. American Civil War: The Definitive Encyclopedia and Document. 2013.

Canal Boats and the Civil War

By Bob Schmidt

Often we’ve heard that troops went to the Civil War in canal boats and returned by train. In actual fact very few soldiers went to war on a canal boat as by the 1860s the railroads were firmly established in the north and canal boats were used largely for freight hauling. Troop movements required the most rapid movement possible. That wasn’t by canal boat.

This is not to say that canal boats did not play a role in the Civil War, they did. One of the first instances was in 1861 when General George B. McClellan was attempting to move troops across the Potomac into Harpers Ferry to restore the Baltimore and Ohio railroad line that had been destroyed by General Stonewall Jackson’s Confederate forces. Although a temporary pontoon bridge had been established for some supplies and troops he needed a more permanent “bridge” across the river to carry cannon and wagons. His engineers in the meantime would repair the “real bridge” that the rebels had also destroyed.

The plan was to bring canal boats off the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal and anchor them in the Potomac River with planks across the beam of the boats. It seemed to be a great plan except when the canal boats reached the Potomac River lock they found that the locks were about 4-6 inches too narrow for the boats to pass through. The river lock was designed to allow smaller boats from the Shenandoah Canal & river to enter the C&O Canal, but not to take C&O canal boats into the Potomac or Shenandoah rivers. The engineers assumed that all canal boats were the same size by their visual inspection and failed to measure the boats in advance. McClellan had to inform Secretary of War Stanton of the problem. President Lincoln was furious. Eventually the permanent bridge was completed. Then troops and supplies flowed across the river and on to Winchester, Virginia.

A second instance occurred on March 8, 1862 when the reconstructed USS Merrimack, now renamed the CSS Virginia, emerged into Hampton Roads as a Confederate ironclad ship. It immediately headed for the Union blockading fleet. With cannon balls bouncing off its side, the CSS Virginia quickly rammed the USS Cumberland, which swiftly sank. As the U.S. captains saw the hopeless situation they tried to avoid contact. The USS Congress surrendered and set afire and the USS Minnesota ran aground.

Panic arouse in Washington as Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton, feared the worse. Even though Secretary of the Navy, Gideon Wells, knew that the USS Monitor was on the way to the Chesapeake Bay, he wondered if she would arrive in time or if her two guns would be able to neutralize the CSS Virginia. As a precaution Lincoln authorized Stanton to be prepare canal boats and other crafts with ballast stone to be sunk, if necessary, in the Potomac to protect the U.S. Capitol at Washington City. If this action became necessary and the CSS Virginia moved up the Chesapeake and the Potomac, the barricade would also interfere with the movement of troops and supplies down river for General McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign that was to start in May near Fort Monroe.

The next day, March 9, 1862, the CSS Virginia emerged into Hampton Roads, was greeted by the USS Monitor, which was protecting the USS Minnesota, and the famous four hour battle of ironclad boats occurred. A day later Gideon Wells received a telegraph message saying that the CSS Virginia had returned to her berth in the Gosport Naval Yard at Portsmouth on the Elizabeth River.

The two ironclads, which had made naval history, never met again. The CSS Virginia (Merrimack) stayed in the Gosport Naval Yard for 2 months until May 9th when the Confederates abandoned the yard and scuttled her as Union troops poured into the Fort Monroe area and threatened Norfolk and the Gosport Naval Yard.

This battle changed the world. European countries halted their construction of wooden ships, the age of the ironclad was at hand. By the end of the war the U.S. Navy had built 84 ironclads, with 64 of them being “Monitor style” vessels, to ply the Mississippi River and the Atlantic Ocean. The term “monitor” had become generic.

A few weeks after the battle, on a trip down the Potomac River with Secretary Stanton on board, Abraham Lincoln passed about 60 canal boats filled with ballast that had not been sunk. In jest, he pointed to them and said, “That is Stanton’s navy!”

Now that the CSS Virginia threat was gone, the Monitor attempted, but failed, to take Drewry’s Bluff on the James River on May 15, 1862. Fort Darling, located on the top of the bluff, is only about 5 miles by river south of Richmond. Confederates sank boats in the river, fired the large cannon from Fort Darling and had sharpshooters hidden along the river bank. The Monitor was unable to silence the batteries on the bluff as she could not elevate the guns on board sufficiently to reach that height. In December the USS Monitor was ordered to Beaufort, North Carolina. She sank in the Atlantic on December 31, 1862 while en route to Beaufort.

The third use of canal boats was by the Confederates bringing in supplies to Richmond on the 196-mile-long James River Canal. As General Grant tightened the siege around Richmond in the Fall of 1864, he sent General Philip Sheridan into the Shenandoah Valley to push back Confederate General Jubal Early and also destroy anything of value to the enemy–crops, railroad tracks & equipment as well as structures on the James River Canal and its canal boats.

There were other areas using canal boats, but perhaps the most unusual one was the transportation of the body of General “Stonewall” Thomas Jackson. Wounded by his own troops at Chancellorsville on May 2, 1863, he passed away on May 12th. His remains were taken to lay in state at the Capital in Richmond. On the 13th his casket was placed on a train and, upon reaching Lynchburg, was removed and placed on a canal boat until it reached Lexington in the evening of May 14th. The entire cadet force of the Virginia Military Institute met the canal boat and escorted his body to his old lecture hall at V.M.I., where they guarded the casket as hundreds passed by. The next morning a funeral service was held at the First Presbyterian of which over 4,000 persons attended. From the service his body was taken by the V.M.I. cadets and a riderless horse to what is today the Stonewall Jackson Memorial Cemetery for burial.

Sources:

Gwynne, S. C. Rebel Yell: The Violence, Passion and Redemption of Stonewall Jackson. New York NY: Scribner. 2014.

Sears, Stephen W. George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon. New York, NY: Ticknor & Fields, 1988.

Snow, Richard. Iron Dawn. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2016.

Symonds, Craig L. Lincoln and His Admirals. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 2008.

We Went “Up and Over”

By Carolyn Schmidt Photos by Bob Schmidt

Twenty-nine Canal Society of Indiana members and friends traveled “Up and Over” the summit of the Wabash & Erie Canal on CSI’s spring tour April 13-14, 2018 from Fort Wayne to Huntington, Indiana. The tour was planned and led by docent Tom Castaldi, CSI director from Fort Wayne, and was easily followed in a 39 page tour guide book written specifically for the event by him. It contained driving directions, pictures of sights and markers seen, and good descriptions of sites we visited.

Registration was held on Friday night in the public hall at the Aboite Township Trustees Office. Those attending received their tour guide book and a packet of information with things to do in Fort Wayne and Huntington as well as maps to the venues. Refreshments of popcorn, iced tea and lemonade were served. Past tour guide books for canals in Indiana and Ohio were sold as well as other books about canals abroad.

The speaker for the Friday evening program was Randy Elliott, who spoke about the part he played in the restoration of several treaty houses built for the Miamis. It was titled “Restoration & Observations: The Chiefs’ House LaFontaine & Richardville.” This gave us information about the early people who lived in the area prior to the Wabash & Erie Canal and the wealth the chief’s accumulated as they controlled the portage between the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River systems. It prepared us for our visit to the Chiefs’ house at the Forks of the Wabash on Saturday. We also learned a lot about architecture and using the proper types of woods in restoring old buildings.

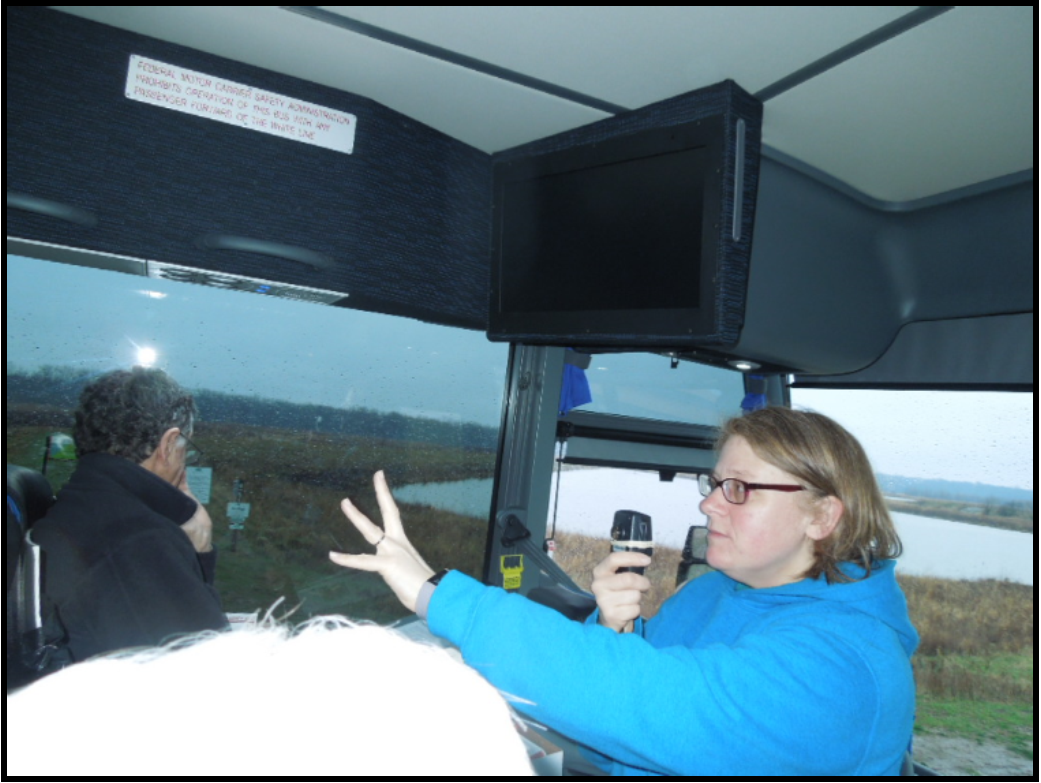

Saturday morning everyone met at the Best Western to board a 38-passenger demonstration coach from Excursion Trailways. Our bus driver was Jim Beuter. His company has ordered a coach like the one we were on. We left a 8 a.m. and headed for the Maumee-Wabash Continental Divide. Although it was raining and the temperature had dropped, we were all eager to take the tour and boarded so fast that we left ahead of the scheduled time.

Saturday morning everyone met at the Best Western to board a 38-passenger demonstration coach from Excursion Trailways. Our bus driver was Jim Beuter. His company has ordered a coach like the one we were on. We left a 8 a.m. and headed for the Maumee-Wabash Continental Divide. Although it was raining and the temperature had dropped, we were all eager to take the tour and boarded so fast that we left ahead of the scheduled time.

Stop 1 was at the divide where we were met by Betsy Yankowiak, Director of Preserves and Programs for the Little River Wetlands’ Project, which has created Eagle Marsh and Towpath Trail. We parked the coach near the earthwork recently built to create a new continental divide to keep Asian Carp from reaching the Great Lakes and she got on board to speak to us about the project. We were nice and dry and could listen to her in comfort.

We also learned how a glacier had influenced the continental divide. It opened an overland portage and created the most direct route between the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River. Its slackwater formed “Lake Maumee.” Its ice blocked the outlet to the north east so that an enormous volume of water passed over the divide and helped carve the huge valley now occupied by the Little Wabash River. Lake Maumee eventually shrank and became Lake Erie. The area it once covered became the Great Black Swamp, which was a great hindrance to the digging of the Wabash & Erie Canal. The glacier also left behind the Great Marsh, a portion of which is now Eagle Marsh. Many attempts were made to drain the marsh but were not successful until the limestone ledge at Huntington was blasted away. Eagle Marsh is now the largest restored wetland in the United States. Birds and animals that once lived there have returned.

Our coach then followed the route of the Wabash & Erie Canal past both the home of Jesse Vermilyea, a canal contractor, and the location of the Aboite Creek Aqueduct, the second aqueduct on the canal from the Ohio-Indiana state line. Some of the stone piers could be seen as we passed by. In the vicinity was the Maryland Settlement and Miami Chief White Raccoon’s village. The Chief thought digging the canal was a crazy idea for there would not be enough water to fill it.

We passed Calf Creek, the location of Canal Culvert No. 34 before arriving in Roanoke to see the location of a widewater turnaround basin with a dock for canal boats to load and unload that were passing through Lock No. 4, Dickey’s Lock. We crossed Cow Creek (now McPherren Drain) where timbers are still visible today from Arch Culvert No. 36 that once carried the canal across the creek. Nearby was a marker for Lock 4.

Stop 2 was at the Roanoke Area Heritage Center, which had several items from the canal era. Of interest was an artist’s painting of Dickey Lock and other canal memorabilia. We were greeted by Kate Hoffman, CSI member from Huntington, who explained some of the canal exhibits.

The coach then passed Roanoke Cemetery where the Mahon brothers, who operated canal boats, and a small girl, who died while passing through the town on a canal boat, are buried. We also passed the road to Port Mahon, which was laid out by Archibald Mahon at the site of a spring. We crossed Bull Creek where Aqueduct No. 3 once stood on stone piers to carry the canal over the creek in a wooden trunk. As we entered Huntington, Indiana we saw where a boat yard that had built canal boats had been and the site of Aqueduct No. 4 over Flint Creek. We passed the site of Lock No. 5 and saw a marker for Lock No. 6, Burk’s Lock, which has been moved from the actual lock site to a corner that has more traffic.

Stop 3 was at the Huntington County Historical Society Museum. Executive Director Mark Stauder greeted us, we were divided into two groups and viewed exhibits about early Huntington, the canal and a piano that was shipped on the Wabash & Erie. We also saw five types of outhouses that we part of one man’s collection. There was an extensive model railroad exhibit as well.

The coach took us past Nick’s Kitchen, which stands in the canal bed and was Vice-President Dan Quayle’s favorite place to eat pork tenderloins. He stood on a chair at the restaurant to announce his candidacy each time he ran for office—Indiana House of Representatives, Indiana Senate, and Vice-President and each time won. The fourth time he stood on the chair and announced his candidacy he was defeated by the Clinton-Gore ticket. The chair is now in the Vice-Presidents Museum.

We saw the marker for the Canal Landing on Washington Street as well as markers for Samuel Huntington and Jefferson Park Mall. Another canal turnaround basin once was located where the parking area for the Huntington Township Library now stands. Nearby was Lock No. 7. A swing bridge crossed the canal on North LaFontaine Street. We saw the Sunken Gardens at Memorial Park, which was once a limestone quarry; a marker for the Lime City as Huntington was once known; and a stone jail used to hold runaway slaves in Civil War times.

Further along we saw land that has recently been purchased by ACRES Land Trust from Our Lady of Victory Missionary Sisters. The Wabash & Erie Canal ran just south of this property. Lambdin P. Milligan’s home, a former canal inn, sat across the canal from the land west of Lock No. 9, Madison’s Lock. Nearby was a marker for the famous court decision of Ex Parte Milligan, which protects civilians from being tried in military courts, even in time of war, if the civil courts are open and functioning. We saw another marker for the Forks of the Wabash before going to lunch.

Stop 4. Everyone was ready for lunch after the busy morning. We ate at The Country Post in Huntington, which served tenderloin sandwiches, a side and a drink to most everyone. Pork tenderloins either breaded or grilled are big in Indiana, especially Huntington. Some canawlers opted for other sandwiches.

Stop 4. Everyone was ready for lunch after the busy morning. We ate at The Country Post in Huntington, which served tenderloin sandwiches, a side and a drink to most everyone. Pork tenderloins either breaded or grilled are big in Indiana, especially Huntington. Some canawlers opted for other sandwiches.

Following lunch we saw a marker for the Home of Chief Richardville before arriving at the Forks of the Wabash Historic Park.

Stop 5. We arrived at the Forks of the Wabash just as they were closing a rummage sale. Some of our members took advantage of the marked down prices. We then gathered at the canal display in the Forks museum to have our group picture taken.

We then split into groups to tour the museum and gift shop, to see the Chiefs’ House, or to walk along Towpath Trail to the site of Lock 10 and Wabash Dam No. 1. In the museum we saw the canal exhibit, an exhibit about the Indians, learned a cute song about a beaver and saw an old school room.

We went inside the Chiefs’ house to learn more about it. It was the restored building we heard about on Friday night. We saw the curved unusual newel post on the staircase.

As we walked the trail Tom Castaldi pointed out the permanent signs sponsored by CSI that tell about the canal. A bridge was under construction to connect to an island in the Wabash River. A dam across the river backed up water and fed it into the canal. We also saw the canal prism and the site of Lock # 10. Along the trail was the Nuck Cabin and an old log school house.

Our coach then passed the site of a dam across Clear Creek that created a pool over which canal boats moved to carry the canal over the stream. Just west of it was the location of a flood-gate that was constructed in the towpath. It could be opened during high water to protect the canal bank from being washed away. This flood gate was removed in 2000.

We then passed the Silver Creek Stone Arch Culvert No. 45, where the creek flowed under the canal. Located west of the arch was Lock No 11, Cheesbro Lock. Today trees grow in what was the lock chamber.

We then passed the Silver Creek Stone Arch Culvert No. 45, where the creek flowed under the canal. Located west of the arch was Lock No 11, Cheesbro Lock. Today trees grow in what was the lock chamber.

We entered the town of Andrews and saw a marker about Lessel Long in Riverside Cemetery. He is noted for his book Twelve Months In Andersonville Prison.

Stop 6 was the Vice Presidential Learning Center Museum where we were met by Executive Director Daniel Johns. Before we saw the artifacts for each Vice-President of the United States, he talked about Indiana’s six Vice-Presidents —Schuyler Colfax under U. S. Grant, Thomas A. Hendricks under Grover Cleveland, Charles W. Fairbanks under Theodore Roosevelt, Thomas R. Marshall under Woodrow Wilson, Dan Quayle under George H. W. Bush, and Mike Pence under Donald Trump — and their relationships to the President at the time. A special exhibit for Dan Quayle, a Huntington native, was on the first floor.

We then saw the La Fontaine Hotel (now senior citizen apartments), the Milligan Block where Lambdin P. Milligan had his law offices, and the bridge over the Little River. We went by a bison farm near Bowerstown, and Mardenis, a station on the Wabash Railroad. Then our coach took us back to the hotel. We had a short time to get to dinner.

Dinner was at Don Hall’s Tavern at Coventry, near the hotel. By ordering ahead of time we were served quickly either broiled haddock, portabella sirloin, beef brisket, or chicken with a salad, baked potato, bread and beverage.

As soon as everyone finished eating we went to the public hall at the Aboite Trustees Office for cupcakes and coffee. Bob Schmidt, CSI president, conducted the annual meeting for the society with an election of one third of the board of directors put forth by Sue Simerman, nomination chairman. Bob then presented a PowerPoint program, “The Canal Society of Indiana on the Panama Canal.”

As soon as everyone finished eating we went to the public hall at the Aboite Trustees Office for cupcakes and coffee. Bob Schmidt, CSI president, conducted the annual meeting for the society with an election of one third of the board of directors put forth by Sue Simerman, nomination chairman. Bob then presented a PowerPoint program, “The Canal Society of Indiana on the Panama Canal.”

Following the meeting CSI directors met to elect officers. Re-elected are Bob Schmidt, President; Mike Morthorst, Vice-President; Sue Simerman, Secretary; and Cynthia Power, Treasurer. Re-elected directors to serve a three year term are Terry Bodine – Covington, Indiana; Phyllis Mattheis – Cambridge City, Indiana; Cynthia Powers – Roanoke, Indiana; Sue Simerman – Ossian, Indiana; and Brian Stirm – Delphi, Indiana. Newly elected director John Hillman – West Harrison, Indiana will also serve a three year term.

Those attending the tour were: Jerry Anderson, Karl & Demi Black, Paul Brandenburg, Tom & Linda Castaldi, Nancy Disbro, Gary & Cassandra Ferris, Don & Betty Haack, Phyllis Hess, Sue Jesse, Jerry & Barbara Lehman, Sam & Jo Ligget, Dan McCain, Mike & Tom Morthorst, Bob & Carolyn Schmidt, Bob Sears, Kay Sheldon, Steve & Sue Simerman, Sherry Spark, and Earl & Marilynn Toops. They came from Canada (2), Illinois (2), Indiana (22 ), and Ohio ( 3). Three others were only able to attend the Friday night event: Tom & Diane Fledderjohann and Ron Morris. One couple from Ohio had to go back home due to an appendicitis attack and Tom had to have his appendix removed. Another came from Indiana and had to return home due to illness.

Gateway Park and Depot Flooded

Heavy rains in early April, reminiscent of the freshets that occurred during canal times, caused the Whitewater River to back up into Duck Creek and flood out the campground and the old railroad depot that is now the banquet hall for the Whitewater Canal Scenic Byways in Metamora, Indiana. Although the Depot was designed to have flood water flow beneath it, this time the water was so high that it came up into the building soaking the floor boards and covering them and the carpeting with mud. Candy Yurchak sent out a plea to Byways members and others in the area to come to the depot on April 7 at 10 a.m. to help clean up the mess caused by the high water. Besides mopping up water and drying out the building, the walls, chairs and tables needed to be washed and dried. Debris needed to be cleared from the park’s campground, field and parking lots. Fortunately, the barn and the Visitors Pavilion & Museum were not reached by the flood.

Heavy rains in early April, reminiscent of the freshets that occurred during canal times, caused the Whitewater River to back up into Duck Creek and flood out the campground and the old railroad depot that is now the banquet hall for the Whitewater Canal Scenic Byways in Metamora, Indiana. Although the Depot was designed to have flood water flow beneath it, this time the water was so high that it came up into the building soaking the floor boards and covering them and the carpeting with mud. Candy Yurchak sent out a plea to Byways members and others in the area to come to the depot on April 7 at 10 a.m. to help clean up the mess caused by the high water. Besides mopping up water and drying out the building, the walls, chairs and tables needed to be washed and dried. Debris needed to be cleared from the park’s campground, field and parking lots. Fortunately, the barn and the Visitors Pavilion & Museum were not reached by the flood.

At the Whitewater Canal State Historic Site flood waters covered the horse pasture and reached the barn where the horses used to pull the canal boat Ben Franklin III are housed. The waters also covered and washed out huge sections of the Whitewater Canal Trail. The trail was quickly repaired and ready for use a few days later. Credit for the repair goes to the Whitewater Canal State Historic Site.

Also in need of repair was the bed for the Whitewater Valley Railroad at Metamora. That will be a much larger project.

Earlier Restoration of Duck Creek Aqueduct

The following article appeared in the Brookville Democrat in 1946 when the Duck Creek Aqueduct that carries the Whitewater Canal over the creek was being restored.

Big Timbers Needed For The Canal Acqueduct

Twelve mammoth yellow poplar timbers are holding up restoration of the Whitewater Canal acqueduct at Metamora because the Indiana Department of Conservation can’t find timbers large enough to do the job.

Thomas G. Mackenzie, state engineer, said restoration of the acqueduct, which is a part of a planned restoration of the historic canal from Metamora to Brookville, cannot continue until the department finds 12 yellow poplar timbers 27 feet long and 10 to 12 inches in girth.

“None of the sawmills we have contacted to date can supply the timers,: Mackenzie said, “and the entire restoration is being held up.”

The state engineer explained that the acqueduct is being restored almost as it was more than 100 years ago and tht the timbers must be yellow poplar.

More than 40,000 board feet of lumber must be purchased before the restoration is completed, he said.

The canal is being turned over to the Conservation department for operation as a state memorial, by the Whitewater Memorial Canal Association.

Now in 2018 the trunk of the aqueduct is being restored, but the covered-bridge style superstructure remains the same. Did they use yellow poplar this time? If so where did they find the timbers?

Welcome New Members

The Canal Society of Indiana welcomes aboard the following new members who have joined at the $20 single/family dues rate unless otherwise noted.

Disbro, Nancy & Jerry Anderson – Markle, IN

Ferris, Gary & Cassandra – Ft. Wayne, IN

Canal Society of Indiana Fall Tour

Miami & Erie Canal – Piqua to New Bremen, Ohio

Friday October 5 – Sunday October 7, 2018

Hotel: Comfort Inn Miami Valley Centre Mall

987 E. Ash St., Piqua, OH 45356 (973) 778-8100

$80 Single/Double + tax

Mention Canal Society of Indiana/Bob Schmidt for group rate which expires 9-21-2018.

The LOCKINGTON LOCKS, a series of six locks which were built between 1837 and 1845, raised and lowered canal boats a total of 67 feet in about a half of a mile. The upper lock, near the “Loramie Summit,” is the high point between Cincinnati and Toledo on the Miami and Erie Canal. These locks were vital to transportation and water supply in the mid nineteenth century.

Follow the route of the Miami & Erie Canal over the summit from Piqua to New Bremen by bus.

Participate in Piqua’s fall festival at the Johnston Farm and Indian Agency where docents tell its history.

Ride the replica canal boat General Harrison.

Experience much, much more.

Tour planner and docent: Andy Hite, Site Manager of the Johnston Farm and Indian Agency

More information and registration forms will be E-mailed to members.